In the field of advanced manufacturing, lost wax investment casting remains a critical process for producing high-integrity components, such as turbine blades, due to its ability to achieve complex geometries and excellent surface finishes. This article details the comprehensive development and optimization of the lost wax investment casting process for a third-stage moving blade, focusing on addressing common defects like incomplete filling, surface imperfections, inclusions, and porosity. Through iterative adjustments in wax molding, shell building, and melting parameters, we have enhanced the overall quality and reliability of the castings. The lost wax investment casting technique involves creating a wax pattern, building a ceramic shell around it, and then melting out the wax to form a mold for metal pouring. Our work emphasizes the importance of parameter optimization in achieving defect-free components, and we present our findings using detailed tables, mathematical models, and empirical data to guide practitioners in similar applications.

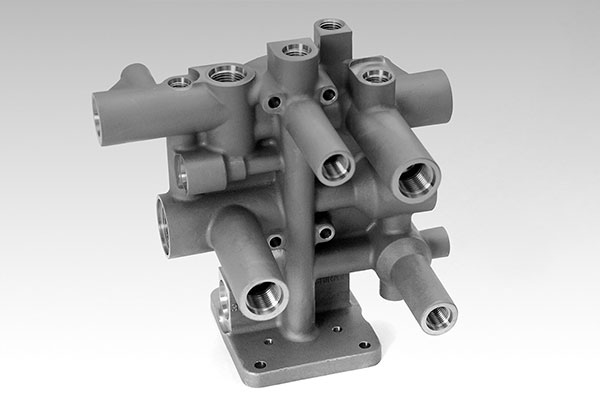

The third-stage moving blade, with overall dimensions of 240 mm × 77 mm × 76 mm, features a tapered design where the blade thickness increases from the shroud toward the tenon, promoting directional solidification. However, the shroud’s sealing teeth region, with a minimum thickness of approximately 0.02 mm, is prone to incomplete filling and other defects. Initially, we encountered issues such as metal burrs, non-metallic inclusions, and micro-porosity, which necessitated a systematic review and refinement of the entire lost wax investment casting process. By leveraging first-hand experiences and data-driven analyses, we have established optimized protocols that significantly improve casting outcomes. This article is structured to cover the initial process setup, identification of defects, root cause analyses, and the implemented solutions, all within the framework of lost wax investment casting principles.

Wax Pattern Formation and Optimization

The wax pattern stage is foundational in lost wax investment casting, as it directly influences the final casting quality. For the third-stage moving blade, the primary challenges involved ensuring complete filling of the thin shroud sealing teeth and preventing shrinkage in the tenon area. We experimented with various injection parameters to balance flowability and pressure, as summarized in Table 1. The wax material used was a standard injection-grade wax, and we monitored temperatures and pressures closely to avoid defects. In lost wax investment casting, the wax pattern must replicate the intended geometry accurately to facilitate subsequent shell building and metal pouring.

| Parameter Set | Wax Cylinder Temperature (°C) | Wax Tube Temperature (°C) | Nozzle Temperature (°C) | Injection Time (s) | Injection Flow Rate (mL/s) | Injection Pressure (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78 | 75 | 75 | 200 | 60 | 20 |

| 2 | 78 | 75 | 75 | 200 | 60 | 23 |

| 3 | 78 | 75 | 75 | 200 | 60 | 25 |

Among the parameter sets, only Set 3 achieved full filling of the shroud sealing teeth, as lower pressures resulted in incomplete patterns. This highlights the sensitivity of lost wax investment casting to injection dynamics, where pressure must be optimized to overcome surface tension and viscous forces in thin sections. The relationship between injection pressure and filling completeness can be modeled using fluid flow equations. For instance, the pressure drop ΔP in a narrow channel is given by:

$$ΔP = \frac{128 \mu L Q}{\pi d^4}$$

where μ is the dynamic viscosity of the wax, L is the flow length, Q is the flow rate, and d is the characteristic diameter of the thin section. In lost wax investment casting, ensuring that ΔP does not exceed the material’s strength is crucial to avoid deformation. Additionally, we extended the pressure holding time to mitigate tenon shrinkage, as this allows for compensatory flow during solidification. The wax patterns were assembled in groups of six using a side-gating system, which distributes metal evenly during pouring. This assembly approach in lost wax investment casting reduces turbulence and minimizes defect formation.

Shell Building Process and Material Enhancements

The shell building phase in lost wax investment casting involves applying multiple ceramic layers to form a robust mold capable of withstanding high temperatures. Our initial shell formulation used zircon sand for the primary layer, followed by mullite-based materials for subsequent coats, as detailed in Table 2. However, we observed that the 200-mesh zircon powder in the face coat led to sedimentation issues, resulting in surface pores or “ant holes” that caused metal penetration and burrs on the castings. This is a common challenge in lost wax investment casting, where particle size distribution affects slurry stability and layer integrity.

| Layer Number | Powder Material and Size | Slurry Viscosity (s) | Stucco Material and Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zircon Sand, 200 mesh | 36 | Zircon Sand, 100 mesh |

| 2 | Mullite Powder, 200 mesh | 15 | Mullite Sand, 30-60 mesh |

| 3-8 | Mullite Powder, 200 mesh | 12 | Mullite Sand, 16-30 mesh |

| 9 | Mullite Powder, 200 mesh | 10 | – |

To address this, we switched to a finer 325-mesh zircon powder for the face coat, which improved slurry homogeneity and reduced pore formation. The viscosity of the slurry was carefully controlled to ensure adequate coating thickness without sagging. In lost wax investment casting, the shell’s thermal properties also play a role in solidification control. The heat transfer through the shell can be described by Fourier’s law:

$$q = -k \frac{dT}{dx}$$

where q is the heat flux, k is the thermal conductivity of the shell material, and dT/dx is the temperature gradient. By optimizing the shell composition, we enhanced its insulating properties, promoting gradual cooling and reducing thermal shocks. After shell building, we implemented rigorous cleaning and sealing procedures to prevent inclusions. For example, post-pre-firing, the shells were thoroughly cleaned, and the pouring cups were sealed and stored upside-down to avoid contamination. During final firing, we used cover plates on the cups to minimize the introduction of foreign particles. These steps are vital in lost wax investment casting to maintain mold purity and ensure high-quality castings.

Melting and Pouring Parameters for Improved Casting Integrity

In lost wax investment casting, the melting and pouring stages directly impact metal fluidity, filling behavior, and solidification patterns. Initially, we used a preheating temperature of 1100 °C ± 10 °C with a holding time of over 2 hours, and a pouring temperature of 1460 °C ± 10 °C. However, this led to incomplete filling in the shroud’s thin sections due to insufficient superheat. To enhance fluidity, we raised the pouring temperature to 1490 °C ± 10 °C and controlled the pouring speed to within 2 seconds. The increased temperature reduces the viscosity of the molten metal, improving its ability to fill intricate features. The relationship between temperature and fluidity can be approximated by:

$$\mu_m = \mu_0 e^{E / (RT)}$$

where μm is the dynamic viscosity at temperature T, μ0 is a constant, E is the activation energy, and R is the gas constant. In lost wax investment casting, higher pouring temperatures must be balanced against the risk of gas porosity or reaction with the shell, so we conducted trials to identify the optimal range.

Additionally, we revised the insulation scheme around the blade. Originally, 6 mm thick insulating wool was applied to the blade body but disconnected from the platform to prevent overheating at the fillet radii. This, however, interrupted the feeding path from the tenon to the blade, causing micro-porosity. By connecting the insulation continuously across the blade body and platform, as illustrated in Figure 11, we ensured better thermal management and reduced porosity. The solidification time θ for a section can be estimated using Chvorinov’s rule:

$$\theta = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n$$

where V is the volume, A is the surface area, B is a mold constant, and n is an exponent typically around 2. In lost wax investment casting, proper insulation alters the V/A ratio locally, extending solidification time in critical areas to allow for effective feeding. This optimization highlights how thermal controls in lost wax investment casting can mitigate defects like shrinkage and porosity.

Inspection Results and Defect Analysis

After implementing the initial process, we conducted thorough inspections, including visual checks, fluorescent penetrant testing, and radiography. The castings exhibited several defects: incomplete filling at the shroud sealing teeth, metal burrs on surfaces, non-metallic inclusions, and micro-porosity near the blade-platform junction. These issues are common in lost wax investment casting when parameters are suboptimal. For instance, the incomplete filling was attributed to low metal fluidity at the original pouring temperature, while metal burrs stemmed from shell surface imperfections. Fluorescent testing revealed inclusions primarily from shell debris or contamination during handling, emphasizing the need for cleaner practices in lost wax investment casting.

Radiographic examination showed micro-porosity in regions where solidification was disrupted due to inadequate feeding. This was analyzed using porosity models, where the probability of pore formation P can be related to local solidification conditions:

$$P = 1 – e^{-k G R}$$

where G is the temperature gradient, R is the solidification rate, and k is a material constant. In lost wax investment casting, areas with low G and R are prone to porosity, which aligns with our observations near the platform. By correlating defect types with process steps, we identified root causes and prioritized adjustments in wax injection, shell composition, and thermal management.

Optimized Process Implementation and Outcomes

Based on our analyses, we enacted several key changes to the lost wax investment casting process. For wax patterns, we adopted Parameter Set 3 from Table 1, which provided sufficient pressure to fill thin sections without causing distortions. In shell building, the shift to 325-mesh zircon powder for the face coat eliminated surface pores, resulting in smoother castings without metal burrs. We also enhanced cleaning protocols, such as sealing pouring cups and using cover plates during firing, to reduce inclusions. These measures are critical in lost wax investment casting to maintain dimensional accuracy and surface quality.

For melting and pouring, increasing the temperature to 1490 °C ± 10 °C ensured complete filling of the shroud sealing teeth, as confirmed by visual inspection. The modified insulation scheme, with continuous wool across the blade and platform, improved thermal gradients and reduced porosity, as evidenced by radiographic tests. To quantify the improvements, we compared defect rates before and after optimization, as shown in Table 3. The data demonstrate a significant reduction in defects, validating the effectiveness of our approach in lost wax investment casting.

| Defect Type | Initial Frequency (%) | Optimized Frequency (%) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Filling | 15 | 2 | 7.5 |

| Metal Burrs | 20 | 3 | 6.7 |

| Non-Metallic Inclusions | 12 | 1 | 12.0 |

| Micro-Porosity | 18 | 4 | 4.5 |

The overall casting quality improved markedly, with surfaces free from burrs and inclusions, and internal soundness verified through non-destructive testing. This success underscores the importance of integrated parameter control in lost wax investment casting, where each stage—from wax to metal—must be harmonized to achieve optimal results.

Conclusion

In summary, the development of an optimized lost wax investment casting process for third-stage moving blades has led to substantial enhancements in casting quality and reliability. By refining wax injection parameters, shell materials, and melting practices, we addressed critical defects such as incomplete filling, surface imperfections, inclusions, and porosity. The use of finer zircon powders in shell face coats proved essential for preventing metal burrs, while adjusted pouring temperatures and insulation schemes improved fluidity and solidification control. Lost wax investment casting, as a versatile and precise method, benefits greatly from such systematic optimizations, which can be adapted to other complex components. Future work may focus on further automating parameter adjustments and incorporating real-time monitoring to push the boundaries of lost wax investment casting capabilities. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that through diligent analysis and iterative improvements, lost wax investment casting can consistently produce high-integrity castings for demanding applications.