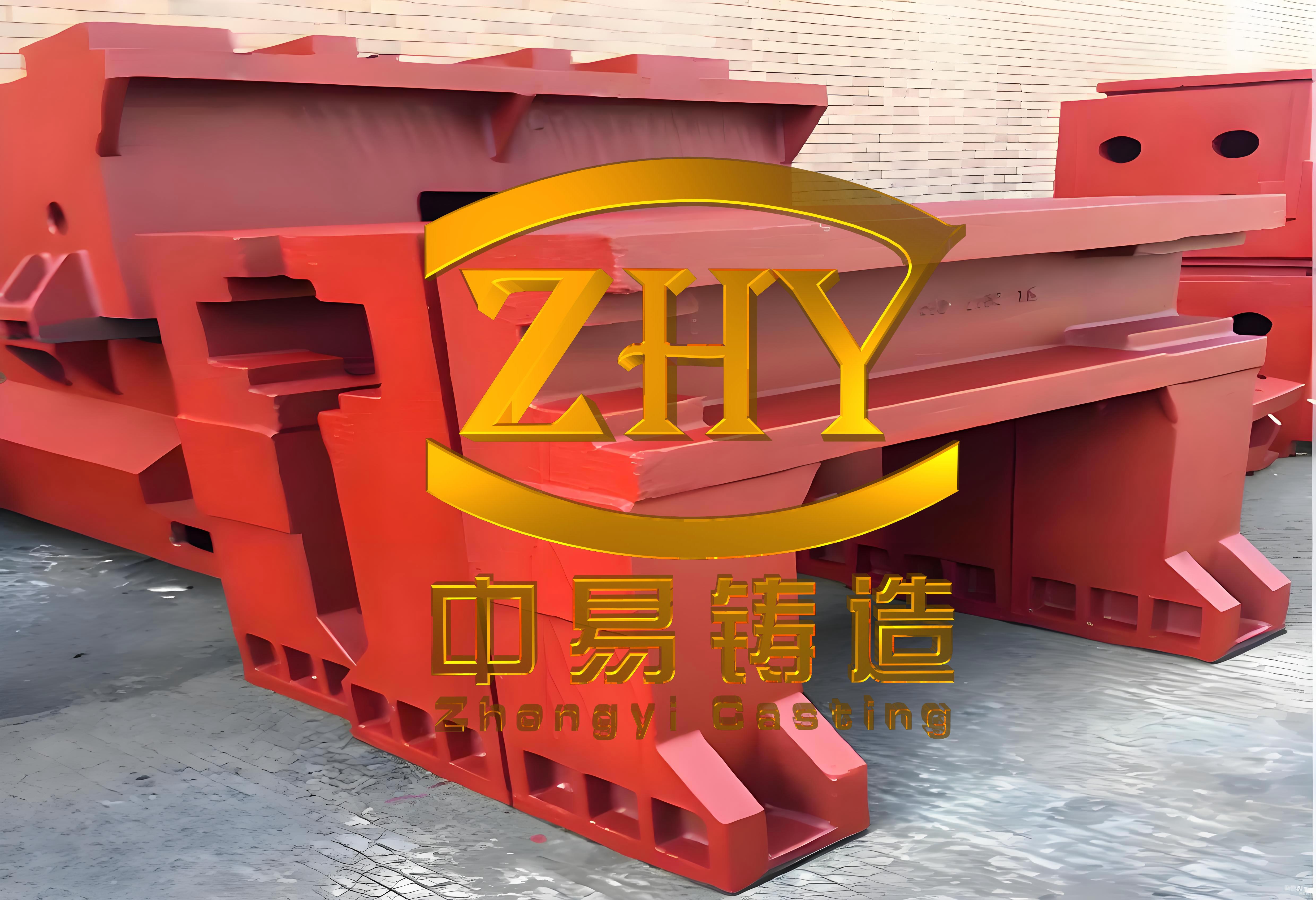

In the production of high-quality machine tool castings, we must analyze the various structural aspects of machine tool components, such as columns and frames, while also developing a deep understanding of casting processes. If inconsistencies in wall thickness occur during casting, significant differences in solidification between thick sections and central areas can lead to defects like shrinkage porosity and voids. Therefore, it is essential to scientifically select appropriate gating systems and employ advanced technologies to prevent such issues. This article delves into the characteristics, common defects, and quality control measures for machine tool castings, emphasizing the use of tables and formulas to summarize key points. The focus remains on enhancing the performance and reliability of machine tool castings through optimized processes.

Machine tool castings are integral to modern manufacturing, particularly in applications requiring high strength and durability, such as in aerospace, marine, and heavy machinery. As we advance into an era of rapid technological innovation, the demand for precision machine tool castings has surged, driving the need for improved casting techniques. In this context, we explore the unique properties of ductile iron used in these castings and how they can be leveraged to achieve superior results. By addressing common challenges and implementing robust quality controls, we can produce machine tool castings that meet stringent industry standards.

The primary material of interest is ductile iron, where carbon precipitates as spheroidal graphite during solidification, unlike the flake graphite in gray iron. This structural modification reduces stress concentration at graphite sites, significantly enhancing the matrix strength and enabling properties comparable to steel. For instance, the tensile strength of ductile iron can be expressed as: $$\sigma_t = \sigma_0 + k \cdot (1 – f_g)$$ where $\sigma_t$ is the tensile strength, $\sigma_0$ is the base strength of the iron matrix, $k$ is a material constant, and $f_g$ is the volume fraction of graphite. Additionally, heat treatments can further improve toughness and other characteristics, making machine tool castings versatile for high-stress environments. We often utilize this in components like lathe beds and milling machine bases, where dimensional stability is critical.

However, the casting process for machine tool castings is prone to several defects that can compromise quality. One common issue is poor nodulization or degradation, where the fracture surface shows silver-gray areas with black spots, and metallographic analysis reveals thick graphite flakes. This typically arises from high sulfur content in the molten iron, leading to reactions with oxygen and the formation of anti-nodulizing elements. To mitigate this, we recommend using low-sulfur carbon sources or treating the carbon to reduce sulfur levels. The reaction can be summarized as: $$ \text{Mg} + \text{S} \rightarrow \text{MgS} $$ where magnesium is used as a nodulizing agent. Table 1 outlines the key factors and countermeasures for this defect.

| Defect Type | Primary Causes | Corrective Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Nodulization | High sulfur content, excessive anti-nodulizing elements | Use low-sulfur materials, add rare earth sulfides, control aeration |

| Shrinkage Porosity | Low carbon, high phosphorus, inadequate mold rigidity | Increase carbon content, enhance mold stiffness with higher resin ratios |

| Graphite Floating | Large initial charge size, high carbon and rare earth content | Control rare earth levels, optimize charge composition |

| Inverse Chill | Presence of Mg, Mn, rapid solidification | Reduce chill-promoting elements, improve furnace intensity, adjust temperature |

| Slag Inclusion | High sulfur, oxidation, magnesium residues | Lower sulfur, minimize air exposure, use rare earth additions, design effective gating |

| Low-TImpact Brittleness | Insufficient energy absorption, material incompatibility | Select high-grade materials suitable for low-temperature applications |

Another significant defect is shrinkage porosity and voids, which occur during the primary and secondary solidification stages, respectively. Shrinkage cavities manifest as surface depressions with rough, dark interiors, while micro-porosity results in distributed voids. This is often due to low carbon levels and high phosphorus, which exacerbate shrinkage. The solidification shrinkage can be modeled using: $$ \Delta V = V_0 \cdot \beta \cdot (T_l – T_s) $$ where $\Delta V$ is the volume change, $V_0$ is the initial volume, $\beta$ is the shrinkage coefficient, and $T_l$ and $T_s$ are the liquidus and solidus temperatures. To address this, we enhance mold rigidity by increasing resin proportions in sand molds, ensuring uniform cooling. For machine tool castings, this is crucial in thick sections like column bases, where thermal gradients are steep.

Graphite floating is a defect where graphite balls rise and aggregate in the upper parts of the casting, leading to “graphite flotation” and reduced mechanical properties. This is primarily caused by oversized charge materials and excessive carbon or rare earth content. We control this by optimizing the charge composition and monitoring rare earth additions. The tendency for graphite floating can be estimated with: $$ C_{eq} = C + 0.3 \cdot Si $$ where $C_{eq}$ is the carbon equivalent, and values above 4.3 often promote floating. By maintaining $C_{eq}$ below this threshold, we minimize the risk in machine tool castings.

Inverse chill appears as bright, white structures in the fracture surface, typically after heat treatment, due to elements like magnesium and manganese that promote chill formation. Rapid solidification rates also contribute. We mitigate this by reducing such elements and increasing furnace reaction intensity. The chill depth $d$ can be related to cooling rate $R$ by: $$ d = k_d \cdot R^{-n} $$ where $k_d$ and $n$ are constants. Adjusting the cooling rate through controlled pouring temperatures helps prevent this in precision machine tool castings.

Slag inclusion involves dark, non-metallic impurities at surfaces or corners, formed in two stages: first, from sulfur reactions producing sulfides, and second, from magnesium oxidation. To combat this, we reduce sulfur levels, limit air exposure by using protective atmospheres, and incorporate rare earth elements to lower slag formation temperatures. The gating system should be designed for smooth, laminar flow with slag traps. For example, the efficiency of slag removal $\eta_s$ can be expressed as: $$ \eta_s = 1 – \frac{C_{slag}}{C_0} $$ where $C_{slag}$ is the final slag concentration and $C_0$ is the initial. This approach is vital for high-integrity machine tool castings used in dynamic loads.

Impact brittleness at low temperatures is another concern, where castings fracture脆ly under stress due to low energy absorption. We address this by selecting advanced materials with better low-temperature toughness, such as high-nickel ductile iron grades. The impact energy $E_i$ can be modeled as: $$ E_i = E_0 \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{T}{T_0}\right) $$ where $E_0$ is the room-temperature energy, $T$ is the temperature, and $T_0$ is a material constant. This ensures that machine tool castings perform reliably in harsh environments, such as in outdoor or cryogenic applications.

Quality control in the casting process begins with mold fabrication. We use multi-layer plywood for molds to enhance strength and resistance to deformation during handling. Surface treatments, such as applying anti-rust and glossy paints, improve durability and finish. For熔炼, we employ large-tonnage electric furnaces to maintain precise temperature control and preheat nodulizing agents to minimize heat loss. The temperature profile during melting can be described by: $$ T(t) = T_0 + \alpha \cdot t – \beta \cdot e^{-\gamma t} $$ where $T(t)$ is the temperature at time $t$, $T_0$ is the initial temperature, and $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ are furnace-specific constants. Post-treatment, we promptly remove slag to maximize furnace efficiency and reuse materials. Table 2 summarizes key process parameters for producing high-quality machine tool castings.

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Influence on Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Pouring Temperature | 1350–1450°C | Affects fluidity and defect formation; higher temperatures reduce viscosity but increase shrinkage risk |

| Carbon Equivalent (Ceq) | 3.8–4.3 | Controls graphite formation; values outside range lead to defects like floating or shrinkage |

| Mold Hardness | 80–90 (B scale) | Ensures dimensional stability; softer molds cause wall movement and voids |

| Nodulizing Agent Addition | 1.2–1.8% of Fe weight | Determines graphite spheroidization; insufficient agent results in flake graphite |

| Cooling Rate | 10–20°C/min | Impacts microstructure; rapid cooling promotes chill, while slow cooling increases segregation |

In applications, machine tool castings are essential for components requiring high stiffness and wear resistance, such as in CNC machine beds, where vibrations must be minimized. The natural frequency $f_n$ of a casting can be approximated by: $$ f_n = \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}} $$ where $k$ is the stiffness and $m$ is the mass. By optimizing the casting process, we achieve better dynamic performance. Moreover, the use of ductile iron allows for weight reduction without compromising strength, which is critical in moving parts like slides and carriages. We continuously refine these processes to meet the evolving demands of industries like automotive and energy, where precision machine tool castings are indispensable.

Looking ahead, the global foundry industry is evolving, with increasing emphasis on sustainability and efficiency. While we have made strides in machine tool casting technologies, there is still a gap compared to leading international standards. We are committed to learning from global best practices, addressing weaknesses, and innovating in areas like digital simulation and real-time monitoring. For instance, solidification modeling using finite element analysis helps predict defect formation, described by equations like the Fourier heat equation: $$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T $$ where $\alpha$ is thermal diffusivity. By integrating such tools, we can preempt issues and enhance yield. Ultimately, these efforts will position us at the forefront of machine tool casting, delivering economic benefits and societal value through reliable, high-performance components.

In summary, the production of high-quality machine tool castings involves a meticulous balance of material science, process control, and defect mitigation. Through systematic approaches, including the use of advanced formulas and tailored parameters, we can overcome common challenges and produce castings that excel in demanding applications. As we push the boundaries of innovation, machine tool castings will continue to play a pivotal role in advancing manufacturing capabilities worldwide.