The evolution of commercial vehicle engines towards higher power densities and increased peak firing pressures has placed significantly greater thermal and mechanical demands on core components, most notably the cylinder head. To meet these demands, the traditional material of choice, alloyed gray iron such as HT300, has been progressively superseded by vermicular graphite cast iron, specifically RuT450. This material upgrade offers superior tensile strength, enhanced yield strength, and improved fatigue resistance. However, this comes at the cost of compromised casting processability. Vermicular iron exhibits a mushy-type solidification mode, more akin to ductile iron than flake graphite iron, leading to a pronounced tendency for shrinkage formation. This inherent characteristic, when combined with the complex geometry of modern high-horsepower cylinder heads—featuring numerous isolated heavy sections like injector bosses, valve guide bosses, and bolt bosses—presents a formidable foundry challenge. This paper details the process research and development undertaken to solve the pervasive issue of shrinkage in casting, specifically shrinkage porosity in these isolated hot spots, for a heavy-duty engine cylinder head produced using a vertical, two-up molding process on an HWS high-pressure molding line.

The casting in question is a six-cylinder head with an approximate weight of 150 kg and overall dimensions of 1070 mm x 340 mm x 165 mm. Its design incorporates numerous features that act as isolated thermal masses. Each cylinder features a central injector boss surrounded by four intake and exhaust valve guide bosses (Ø26 mm). Furthermore, four rows of bolt bosses (Ø29 mm) are distributed from the intake to the exhaust side, totaling 38 bosses across the head. A main oil gallery (Ø20 mm) runs the length of the casting, intersecting with valve seat rings and camshaft bearing caps, creating complex cross-junction hot spots. The combination of this geometry with the solidification characteristics of vermicular iron creates a high propensity for shrinkage in casting, particularly in the form of micro-shrinkage or porosity within these thick sections, which is unacceptable on machined surfaces.

| Parameter | Specification / Target |

|---|---|

| Material | RuT450 (Vermicular Graphite Iron) |

| Key Mechanical Properties | Tensile Strength ≥ 430 MPa, Hardness 200-250 HB |

| Vermicularity on Fire Deck | ≥ 80% |

| Chemical Composition (wt.%) | C: 3.6-3.9, Si: 1.8-2.3, Mn: 0.4-0.9, P≤0.07, S≤0.025, Cu: 0.4-1.2, Sn: 0.06-0.13 |

| Critical Quality Requirement | Machined surfaces of injector holes, guide holes, and bolt holes must be free from shrinkage in casting defects. |

The initial production process employed a vertical stack molding configuration with two castings per mold. The gating system was a bottom-feeding, single-level design, with the sprue located at the parting line and runners channeling metal along the exhaust-side bottom of the mold cavity before being introduced through six ingates. A key feature was the use of cylindrical external chills (Ø20 mm x 20 mm) placed in the core at locations corresponding to bolt bosses. Iron was treated using a conventional sandwich method for vermiculization, with process control based on quick thermal analysis and microscopic examination. Melt quality was later enhanced by implementing a wire-feeding treatment process coupled with an OCC (Optical Columnar Curvature) vermicularity measurement system for real-time, precise control, aiming for a consistent vermicularity range of 80-95%.

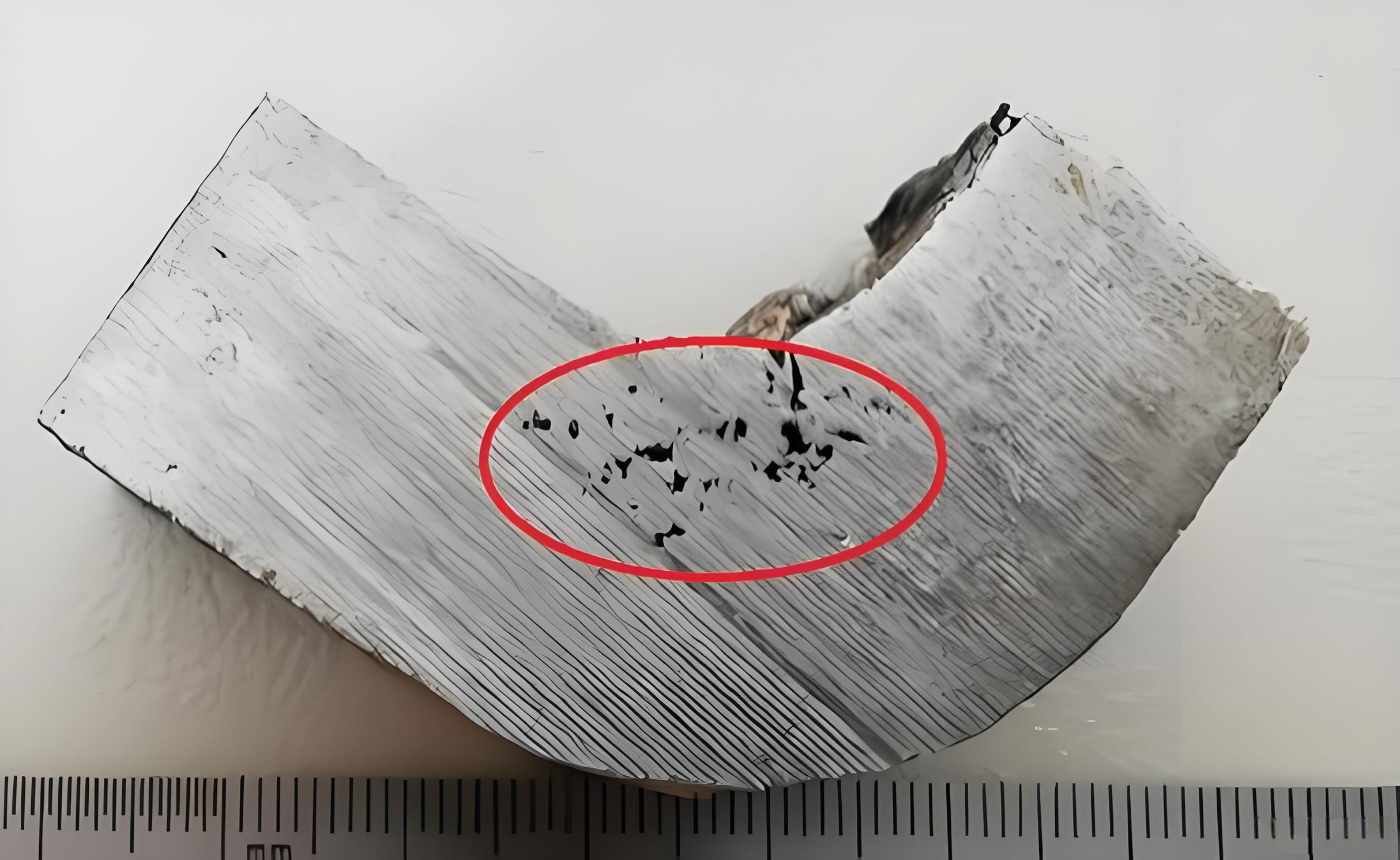

Despite these measures, machining of the initial trial castings revealed a high incidence of shrinkage in casting defects. The most severe shrinkage porosity was found in the bolt holes between cylinders 3 and 4, typically located 50-70 mm from the bottom face within the region where the bolt boss intersects the water jacket core. Analysis indicated that the bottom-running gating system heated the sand in the lower mold regions, adversely affecting the cooling conditions for these lower bolt bosses. Furthermore, the vertical orientation and the isolated nature of these hot spots meant that feed metal from the upper parts of the casting could not effectively reach and compensate for the solidification shrinkage in these regions.

To systematically address this core issue of shrinkage in casting, a series of process trials were designed and executed. The guiding principle was that in a vertical casting process, the effectiveness of risers is often limited by geometry, necessitating a combined approach of controlled feeding and accelerated local cooling.

Process Improvement Trials and Analysis

Trial 1: Enhanced Feeding and Chill Modification

The first modification focused on improving feeding to the most problematic lower bosses. The original external cylindrical chills for the second-row bolt bosses were replaced with a more substantial open feeder (hot riser) placed at the mold parting line. For the lower-row bosses, the cylindrical chills were changed to elongated bar-type external chills to increase their heat extraction capacity. Additionally, annular internal chills were introduced into the core prints for the valve guide bosses.

| Change | Objective | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Open Feeder on 2nd Row | Provide direct liquid feed to the hot spot. | Effectively eliminated shrinkage in the 2nd row bosses. |

| Bar-type External Chills | Increase heat sink mass and contact area. | Reduced but did not eliminate shrinkage in the 3rd row. |

| Annular Internal Chills in Guides | Accelerate cooling at the guide bore core. | Reduced leakage frequency but introduced fusion defects and gas porosity. |

The trial confirmed that a properly sized riser could effectively feed adjacent thick sections. However, the feeder’s influence was limited by distance, failing to reach the deeper sections of the lower bosses. The annular chills, while theoretically sound, posed practical issues with fusion and gas entrapment, making them unsuitable for mass production. The fundamental challenge of shrinkage in casting in deep, isolated sections persisted.

Trial 2: Reduction of Geometric Hot Spot Modulus

Since direct feeding was challenging, the next approach aimed to reduce the thermal modulus of the hot spots themselves by casting the holes for the bolts and guides, leaving only a minimal 2 mm machining allowance. This transforms a solid cylindrical mass into a hollow one, significantly reducing its volume-to-surface area ratio, a key driver for shrinkage formation. The solidification time \( t_s \) for a simple shape can be approximated by Chvorinov’s Rule:

$$ t_s = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where \( V \) is volume, \( A \) is surface area, \( B \) is a mold constant, and \( n \) is an exponent (typically ~2). By casting the hole, \( V \) decreases dramatically while \( A \) increases, leading to a much shorter \( t_s \) and reducing the time window for shrinkage in casting to form.

The bolt holes were cast blind to a depth of 70 mm from the bottom face, while the guide holes were cast through. Machining results showed the cast-hole sections themselves were largely free of shrinkage porosity. However, a small band of shrinkage often appeared just above the termination of the cast bolt hole. Furthermore, maintaining the precise dimensional stability of these small, deep core prints during molding, core handling, and metal pouring proved extremely difficult, leading to unacceptable machining scrap rates. This solution, while effective against the defect, introduced an even greater problem of dimensional variation.

Trial 3: Integrated Internal-External Chill System

The lessons from previous trials converged on a solution: if feeding is difficult and geometric modification is impractical, the most reliable method to prevent shrinkage in casting is to forcibly control the solidification sequence by drastically accelerating the cooling of the isolated hot spot. This requires a chill system with high heat extraction capacity and the ability to act from within the thermal center. A combined internal-external chill system was designed. Steel pins were inserted as internal chills into the core prints for the bolt and guide bosses. These pins protruded from the core and made contact with external chill blocks placed in the mold, creating a continuous high-conductivity heat path from the center of the hot spot to the massive mold wall.

The effectiveness of a chill depends on its ability to absorb heat and its thermal diffusivity. The heat extracted \( Q \) by a chill can be expressed as:

$$ Q = \int \rho c_p \Delta T \, dV $$

where \( \rho \) is density, \( c_p \) is specific heat, and \( \Delta T \) is the temperature rise of the chill material. To be effective, the chill must have a high volumetric heat capacity (\( \rho c_p \)) and a high thermal diffusivity \( \alpha \):

$$ \alpha = \frac{k}{\rho c_p} $$

where \( k \) is thermal conductivity. A high \( \alpha \) allows heat to rapidly conduct into the body of the chill. Steel provides an excellent balance of these properties, high melting point (preventing fusion), and cost-effectiveness compared to copper or specialized alloys.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulation was used to optimize the design. The initial chill design showed a steep thermal gradient, with the tip in contact with the casting becoming saturated quickly. The solution was to significantly increase the length and mass of the external portion of the chill assembly. Simulation results (shown conceptually below) confirmed that the modified design resulted in a much flatter temperature profile along the chill, indicating sustained heat extraction capability and preventing the formation of a secondary hot spot at the chill root, which could itself lead to shrinkage in casting.

| Material | Relative Cooling Power (Sand=1) | Key Properties for Chill Design |

|---|---|---|

| Copper | 4.05 | Highest conductivity, expensive, can fuse. |

| Steel | 3.95 | High strength, good conductivity/heat capacity, cost-effective. |

| Graphite | 3.34 | Good conductivity, low wettability, fragile. |

| Chromite Sand | 1.56 | Marginally better than silica sand, not sufficient for severe hot spots. |

| Silica Sand | 1.00 | Baseline. |

Machining of trial castings with the optimized steel pin chill system showed a dramatic reduction in defect rates, exceeding 90% improvement over the initial process. Crucially, metallographic examination confirmed that the presence of the steel chill did not adversely affect the vermicularization of the surrounding iron matrix, and the chill remnants were easily removed during subsequent drilling operations.

Finalized Production Process and Discussion

The successful trial results were incorporated into the finalized, mass-production process. The definitive strategy to conquer shrinkage in casting in this vertical-poured vermicular iron cylinder head is a holistic one, combining metallurgical control, feeding, and aggressive chilling:

- Gating and Feeding System: The bottom-feeding gating was retained but carefully balanced to ensure smooth filling. Where geometry permitted, small blind risers were used to feed accessible heavy sections.

- Comprehensive Chill Strategy:

- Injector Bosses: The sand core for the injector tube is manufactured with an integrated internal chill.

- Bolt and Guide Bosses: A system of steel pin internal chills, coupled with designed external chill blocks in the mold, is used for every relevant boss location. This system creates a directional solidification front pushing from the chill towards the nearest feeding source or thinner section.

- Metallurgical Precision: The use of wire-feeding treatment and the OCC process control system ensures consistent high vermicularity (80-95%), which optimizes the material’s innate shrinkage characteristics. While higher vermicularity generally reduces shrinkage tendency compared to lower, erratic vermicularity is a major source of variable shrinkage in casting defects.

The interplay between feeding distance and chill effectiveness is critical. In a vertical casting, the effective feeding distance \( L_f \) from a riser is less than in a horizontal one due to gravitational effects. The use of chills effectively reduces the required feeding distance for an isolated section by turning it into a “fed” zone via rapid solidification. The combined system ensures that every isolated hot spot is either within a reduced \( L_f \) or is forcibly solidified before the feeding paths freeze.

Furthermore, the mechanism of shrinkage in casting formation in vermicular iron is distinct. The expanded solidification range and the growth morphology of the vermicular graphite create a pasty zone that can block interdendritic feeding. The pressure drop \( \Delta P \) required for feeding through this mush is given by the Darcy equation:

$$ \Delta P = \frac{\mu \dot{V} L}{K A} $$

where \( \mu \) is viscosity, \( \dot{V} \) is volumetric feeding rate, \( L \) is length of the mushy zone, \( A \) is cross-sectional area, and \( K \) is permeability. A long mushy zone (large \( L \)), as found in thick sections, drastically increases \( \Delta P \). If this exceeds the metallostatic pressure, shrinkage in casting occurs. Chills directly attack this problem by reducing \( L \), shortening the mushy zone and increasing permeability \( K \) in the final stages of solidification.

Conclusion

The challenge of preventing shrinkage in casting, particularly micro-shrinkage porosity in isolated hot spots, in complex vermicular iron castings produced via vertical molding processes requires a multifaceted engineering solution. Relying solely on risers is insufficient due to geometric constraints on feeding channels and distances. Conversely, chills alone cannot provide the macroscopic volume compensation required during solidification. This case study demonstrates that a successful strategy must be integrated:

- Strategic Feeding: Employ risers for all geometrically feasible heavy sections to provide liquid metal reserve.

- Aggressive and Intelligent Chilling: For numerous, dispersed, and deeply embedded hot spots like bolt and guide bosses, internal chills or combined internal-external chill systems are the most effective and reliable solution. They work by fundamentally altering the local solidification kinetics, reducing the thermal modulus and shortening the mushy zone, thereby mitigating the root cause of shrinkage in casting.

- Process Stability: Precise control of the vermiculization process to achieve consistently high vermicularity is essential to minimize the inherent shrinkage tendency of the iron and ensure predictable process outcomes.

- Design for Manufacturability (DFM): Where possible, collaborating with product design to incorporate cast holes (reducing the thermal modulus) can be a highly effective solution, though it requires careful attention to core stability and dimensional control.

In summary, the battle against shrinkage in casting in advanced castings like vermicular iron cylinder heads is won through a combination of thermal management—using chills to control solidification sequence at a local level—and hydraulic management—using the gating and risering system to ensure adequate liquid pressure and supply. This integrated approach ensures the production of sound, high-integrity castings capable of meeting the severe demands of modern high-performance engines.