In my extensive experience with vacuum expendable pattern casting (EPC) for producing air-cooled die steel components, I have consistently encountered the challenge of porosity in casting. This defect, characterized by voids or gas pockets within the cast structure, severely compromises the mechanical integrity and surface quality of parts, leading to high rejection rates. For years, our foundry supplied critical die steel castings to automotive manufacturers, and the persistent issue of porosity in casting threatened production timelines and quality standards. This article details my first-hand investigation into the root causes and the systematic, evidence-based solutions developed to entirely eliminate porosity in casting for these components. I will present a comprehensive analysis, supported by experimental data, formulas, and tables, to elucidate the mechanisms and provide a replicable framework for addressing porosity in casting in vacuum EPC applications.

The vacuum EPC process, while excellent for dimensional accuracy and surface finish, inherently involves the decomposition of a foam pattern upon contact with molten metal. This decomposition generates substantial volumes of gas. If this gas is not efficiently evacuated through the coating and sand medium, it becomes trapped within the solidifying metal, leading to porosity in casting. Our specific challenge involved air-cooled die steel grades, typically weighing around 10 kg with section thicknesses below 50 mm. Despite rigorous melting and deoxidation practices—using medium-frequency induction furnaces, sequential deoxidation with silicon-aluminum-iron, silicon-calcium powder, and final aluminum and rare-earth treatments—the castings exhibited extensive surface and subsurface porosity in casting. This indicated that the source was not inherent gas content in the steel melt, which was confirmed through gas content tests, but rather the interaction between the process materials and the high-temperature steel.

My analysis focused on three primary factors: coating thickness, coating composition, and foam pattern density. Each factor contributes significantly to the overall gas evolution and venting capacity, directly influencing the severity of porosity in casting.

1. The Critical Role of Coating Thickness and Permeability

Initially, the coating protocol involved applying 3-4 layers of a quick-drying coating based on 270-mesh quartz powder, resulting in a thickness (δ) of 2-3 mm. The primary function of the coating is to provide a barrier while allowing gaseous decomposition products to escape. I hypothesized that excessive thickness severely reduced permeability, trapping gases and causing porosity in casting. The permeability (K) of a coating layer can be conceptually described by a relation similar to Darcy’s law for flow through porous media:

$$ J = -\frac{K}{\mu} \frac{dP}{dx} $$

where \( J \) is the gas flux, \( \mu \) is the gas viscosity, and \( \frac{dP}{dx} \) is the pressure gradient. A thick coating increases the path length \( x \), reducing the pressure gradient for a given vacuum level and thus impeding gas flux. To quantify this, I conducted a production trial. Using a single heat of steel, I poured multiple castings in the same flask, varying only the coating thickness. The results were stark and are summarized in Table 1.

| Coating Thickness Range (mm) | Number of Castings Produced | Number of Castings with Porosity | Porosity in Casting Defect Rate (%) | Relative Gas Venting Efficiency (Qualitative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 – 1.5 | 78 | 5 | 6.4 | High |

| 2.0 – 3.0 | 52 | 19 | 36.5 | Low |

The data conclusively shows that reducing the coating thickness from 2-3 mm to 0.5-1.5 mm decreased the porosity in casting defect rate by approximately 82%. This confirms that coating thickness is a dominant variable controlling gas egress and a major contributor to porosity in casting.

2. Chemical Interactions Between Coating and Molten Steel

A second, more subtle cause of porosity in casting was identified through comparative observation. When producing ordinary carbon steel castings using the same coating and thickness, porosity in casting was minimal. The air-cooled die steel, however, contains significant levels of carbon and chromium (e.g., typical compositions involve >0.5% C and 5-12% Cr). At the high pouring temperatures exceeding 1650°C, thermochemical reactions become feasible. I postulated that chromium in the melt could reduce silica (SiO₂) from the quartz-based coating:

$$ \text{2Cr (in steel)} + \text{SiO}_2 (\text{coating}) \rightarrow \text{2CrO} + \text{Si} $$

The chromium oxide (CrO) formed, being unstable at high temperatures, can subsequently be reduced by the abundant carbon in the steel:

$$ \text{CrO} + \text{C (in steel)} \rightarrow \text{Cr} + \text{CO} \uparrow $$

The generation of carbon monoxide (CO) gas at the metal-coating interface provides a direct source for pore formation, exacerbating porosity in casting. The overall driving force for such reactions can be assessed using the Gibbs free energy change, \( \Delta G \), for the coupled reaction at temperature T:

$$ \Delta G = \Delta H – T\Delta S $$

Where a negative \( \Delta G \) indicates spontaneity. The high temperature and activity of Cr and C in die steel make this reaction sequence thermodynamically favorable. To test this, I performed a comparative trial using coatings of different compositions but identical thickness (2-3 mm). The results are presented in Table 2.

| Coating Primary Constituent | Chemical Nature | Number of Castings Sampled | Porosity in Casting Defect Rate (%) | Postulated Gas Generation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Powder (SiO₂) | Acidic | 36 | 27.8 | High: SiO₂ reduction by Cr/C generates CO. |

| Alumina (Al₂O₃-based) | Basic/Neutral | 31 | 12.9 | Low: Chemically inert to Cr, minimal gas generation. |

The use of alumina-based coating nearly halved the incidence of porosity in casting, strongly supporting the hypothesis that chemical gas generation is a significant factor for alloy steels rich in strong carbide formers like chromium. This interaction is a critical, often overlooked, source of porosity in casting for alloy steel EPC.

3. Foam Pattern Density and Gassing Characteristics

The third factor I investigated was the foam pattern itself. Originally, patterns with a density (ρ) of 35-45 × 10⁻³ g/cm³ were used to ensure sufficient mechanical strength during coating application, assembly, and molding. However, the mass of decomposable polymer directly correlates with the total gas volume (V_gas) produced upon pyrolysis. Assuming complete decomposition to gaseous products (a simplification), the gas volume can be approximated by:

$$ V_{gas} \propto m_{foam} = \rho_{foam} \cdot V_{pattern} $$

A higher density foam leads to a greater mass \( m_{foam} \) for the same pattern volume \( V_{pattern} \), thereby increasing the gas load that the coating must vent. Furthermore, incomplete combustion can yield liquid or solid residues that may clog the porous coating structure, effectively reducing its instantaneous permeability and trapping gas. This creates a dual problem: more gas is generated, and the pathway for its escape is more likely to be obstructed, synergistically promoting porosity in casting.

Integrated Solution Strategy: A Multi-Pronged Attack on Porosity in Casting

Based on this root cause analysis, I developed and implemented a set of interconnected process modifications aimed holistically at minimizing gas generation and maximizing gas evacuation to eliminate porosity in casting.

3.1 Minimizing Gas Generation from the Foam Pattern

First, I specified a lower-density expanded polystyrene (EPS) sheet of 20-25 × 10⁻³ g/cm³ for pattern fabrication. This directly reduces \( m_{foam} \) and thus the source term for gas. Second, and more innovatively, I introduced hollow pattern construction. For gating elements (sprue, runners, risers) and for casting sections thicker than 30 mm, the core of the foam was removed, leaving a shell of controlled thickness. The governing equation for the mass reduction is:

$$ \Delta m = \rho_{foam} \cdot (V_{solid} – V_{hollow}) $$

For a cylindrical section of outer radius R and inner radius r, the mass reduction is:

$$ \Delta m = \rho_{foam} \cdot \pi L (R^2 – r^2) $$

Where L is the length. We standardized shell thicknesses: 10-12 mm for gating and 12-15 mm for thick casting sections. This hollow design drastically cuts the gas load without compromising pattern handling strength, addressing a fundamental source of porosity in casting.

3.2 Optimizing Coating Thickness and Application Strategy

To enhance coating permeability, I mandated a substantial reduction in overall thickness. However, maintaining adequate green and fired strength was paramount to prevent pattern distortion or erosion. This was achieved by reformulating the coating slurry: blending 200-mesh and 270-mesh refractory powders to improve particle packing and strength, and using a combination of high-temperature (e.g., silica sol) and room-temperature (e.g., organic binders) binders. Crucially, I abandoned uniform coating application. Recognizing that solidification rates vary across a casting, I implemented a differential coating strategy. Areas prone to rapid heat dissipation, such as edges and corners, receive a thin coating (δ = 0.5-1.0 mm) to maximize local gas venting. Areas with slower solidification, like thick sections, receive a slightly thicker coating (δ = 1.0-1.5 mm) to withstand metal pressure for a longer duration. This strategy optimizes the local balance between strength and permeability. The coating thickness on the gating system was also reduced to 1-1.5 mm to ensure gases from the massive foam decomposition in the sprue and runners are vented away from the mold cavity, preventing their ingress and subsequent contribution to porosity in casting.

3.3 Selecting Chemically Inert Coating Materials

Permanently, I replaced the quartz-based coating with an alumina (Al₂O₃)-based coating. Alumina is thermodynamically more stable than silica in the presence of chromium and carbon at casting temperatures. The free energy change for any potential reduction reaction of Al₂O₃ by chromium is highly positive, making it effectively inert:

$$ \Delta G_{(\text{Cr} + \text{Al}_2\text{O}_3)} \gg 0 \quad \text{at } T > 1650^\circ\text{C} $$

This eliminates the in-situ chemical generation of CO gas at the interface, removing a key mechanism for pore nucleation. The coating formulation was adjusted for optimal viscosity, suspension, and drying characteristics to suit the new refractory base.

The combined impact of these measures can be modeled conceptually. The net tendency for porosity in casting (P) can be expressed as a function of key variables:

$$ P \propto \frac{(\text{Gas Generation Rate})}{(\text{Gas Evacuation Rate})} $$

Where:

– Gas Generation Rate = \( f(\rho_{foam}, V_{foam}, \text{chemical reactions}) \)

– Gas Evacuation Rate = \( g(K_{coating}, \delta_{coating}, \text{vacuum pressure}) \)

Our modifications target both the numerator and denominator:

1. Reducing \( \rho_{foam} \) and \( V_{foam} \) via hollow patterns decreases the Gas Generation Rate.

2. Eliminating chemical reactions by using Al₂O₃ coating further decreases the Gas Generation Rate.

3. Reducing \( \delta_{coating} \) and optimizing \( K_{coating} \) through particle sizing increases the Gas Evacuation Rate.

Therefore, the overall ratio P decreases significantly, leading to the elimination of porosity in casting.

4. Results and Long-Term Performance

The implementation of this integrated approach yielded transformative results. The quantitative improvement is summarized in Table 3, comparing the old and new processes over a significant production volume.

| Process Parameter / Outcome | Original Process | Optimized Process | Improvement Factor / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Coating Thickness (mm) | 2.5 | 1.0 (variable) | 60% reduction on average |

| Coating Composition | Quartz (SiO₂) | Alumina (Al₂O₃) | Eliminates chemical gas generation |

| Foam Pattern Density (g/cm³) | 40 × 10⁻³ | 22.5 × 10⁻³ | ~44% reduction in foam mass |

| Pattern Design | Solid | Hollow (for gating & thick sections) | Further 30-50% reduction in local foam mass |

| Porosity in Casting Defect Rate (%) | ~30-40 (typical) | ~0.5-1.0 (sporadic, non-critical) | >95% reduction in defect rate |

| Casting Yield Improvement (%) | Baseline | +35 (estimated) | Due to near-zero scrappage from porosity |

| Surface Quality | Often marred by surface pores | Consistently sound and smooth | Direct benefit of eliminating surface porosity in casting |

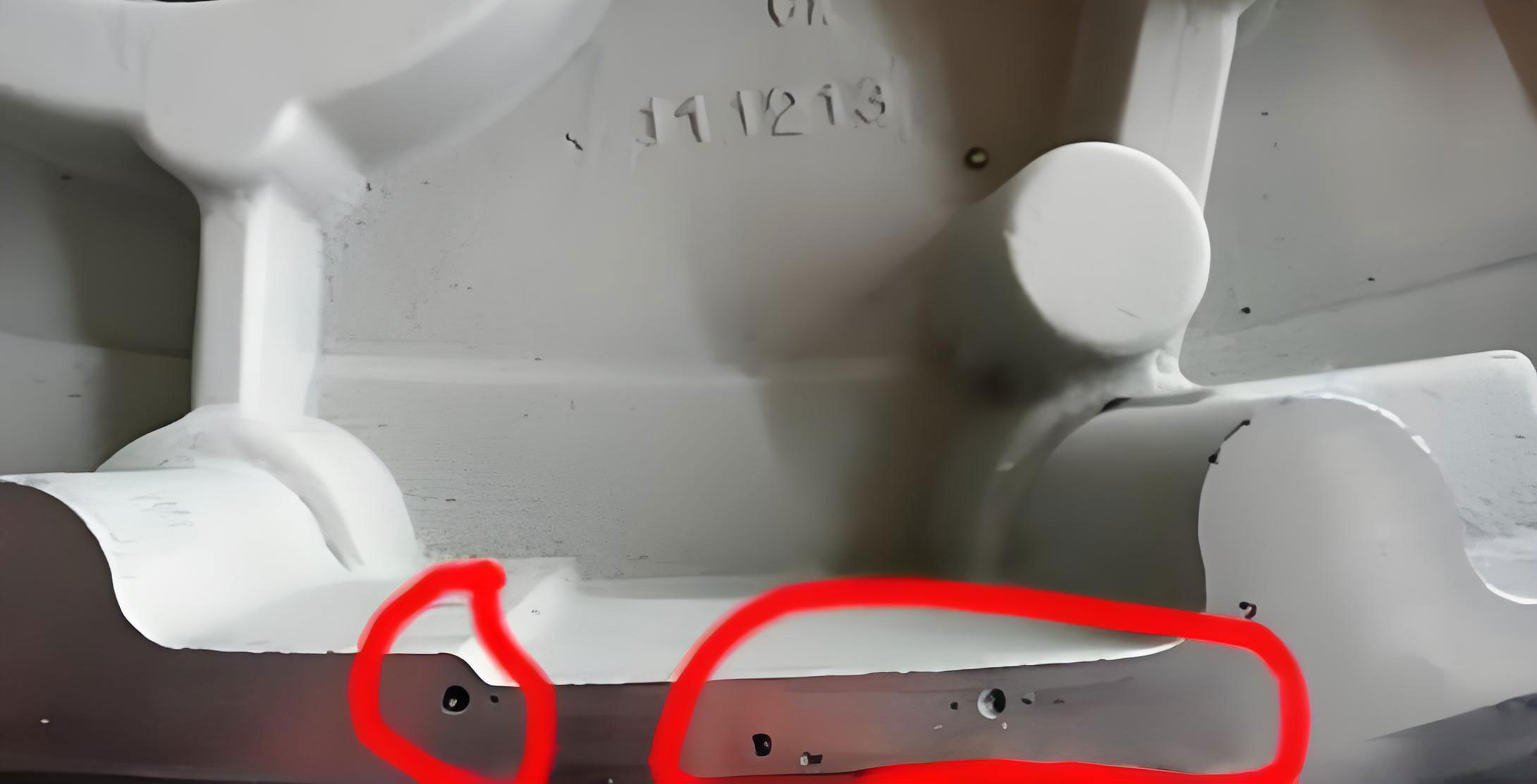

Following the full implementation, our foundry has successfully produced nearly one hundred tons of air-cooled die steel castings. Not a single casting has been scrapped due to porosity in casting defects. The consistency and reliability of the process have improved dramatically. The problem of porosity in casting, which once plagued production, is now considered resolved. The soundness of the castings has been verified through radiographic inspection, dye penetrant testing, and functional performance in their applications as forging dies and automotive tooling.

5. Generalized Principles and Formulas for Porosity Mitigation in EPC

The lessons learned extend beyond air-cooled die steel. The framework for addressing porosity in casting in vacuum EPC can be generalized. I propose a systematic evaluation checklist and calculation aids for foundries facing similar issues.

Porosity Risk Index (PRI) – A Conceptual Formula:

While precise quantification is complex, a semi-empirical index can guide process parameter selection:

$$ PRI = \frac{ \left( \frac{\rho_{foam}}{20} \right) \cdot \left( \frac{\delta_{coat}}{1.0} \right) \cdot \left( \text{Chemical Reactivity Factor, CRF} \right) }{ \left( \text{Permeability Factor, PF} \right) \cdot \left( \frac{P_{vac}}{50} \right) } $$

Where:

– \( \rho_{foam} \) is in \(10^{-3} \, \text{g/cm}^3\) (reference 20).

– \( \delta_{coat} \) is average coating thickness in mm (reference 1.0).

– CRF: 1.0 for inert coatings (Al₂O₃, zircon), 2.5-3.0 for reactive coatings (SiO₂ with high Cr/C steels).

– PF: 1.0 for standard coatings, >1.5 for optimized, high-permeability blends.

– \( P_{vac} \) is applied vacuum in kPa (reference 50 kPa).

A lower PRI indicates a lower risk of porosity in casting. Our optimization moved PRI from a value >>1 to a value <<1.

Decision Matrix for Coating Selection:

| Alloy Type / Key Elements | Recommended Coating Base | Rationale | Risk of Chemical Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon & Low-Alloy Steels | Quartz (SiO₂) or Alumina | Low reactivity; cost may dictate choice. | Low |

| High-Chromium Steels (Die Steels, Stainless) | Alumina (Al₂O₃), Zircon (ZrSiO₄), Magnesia (MgO) | Inert to reduction by Cr/C. Essential to prevent gas generation. | High if using SiO₂ |

| High-Manganese Steels | Basic coatings (MgO-based) | Resists interaction with MnO. | Moderate |

| Cast Iron | Graphite-based, Alumina | Compatibility with high C content. | Low |

6. Conclusion

Through meticulous investigation and controlled experimentation, I identified the multifaceted origins of porosity in casting for vacuum EPC air-cooled die steel components. The defect was not monochromatic but resulted from the confluence of excessive gas generation (from dense foam and chemical reactions) and restricted gas evacuation (from thick, low-permeability coatings). The solution required an integrated, synergistic approach: radically reducing foam mass via lower density and hollow designs; slashing coating thickness and applying it differentially to balance strength and permeability; and switching to a chemically inert alumina-based coating to eliminate in-situ gas generation. The result has been the virtual eradication of porosity in casting from our production, transforming a major quality bottleneck into a reliable, high-yield process. This case underscores that combating porosity in casting in advanced casting processes demands a holistic understanding of materials interactions, fluid dynamics, and solidification science. The principles and strategies detailed here—emphasizing the control of gas sources and the optimization of venting pathways—provide a robust template for addressing similar challenges with porosity in casting across a wide spectrum of alloys and casting geometries in the expendable pattern casting domain.

The continuous monitoring of parameters like foam density, coating viscosity and thickness, and vacuum level remains essential for consistent quality. Future work could involve developing real-time sensors to monitor back-pressure in the mold during pouring, providing direct data to further refine the process window and ensure zero-defect production against porosity in casting. The battle against porosity in casting is won through persistent inquiry, data-driven adjustments, and a willingness to challenge established practices.