Investment casting, often referred to as lost-wax casting, is a precision manufacturing process that has experienced a notable resurgence in recent years, driven by advancements in materials and technology. Despite its capabilities for producing intricate and high-tolerance components, the process is frequently marred by high defect rates, with porosity in casting standing out as a predominant issue. Porosity in casting manifests as voids or cavities within the cast metal, which can critically undermine mechanical strength, fatigue resistance, and overall part reliability. This defect is particularly prevalent when water glass (sodium silicate) is employed as a binder in shell mold construction. Through extensive practical experience and analysis, I aim to comprehensively explore the root causes of porosity in casting in such systems and present effective preventive strategies. The discussion will encompass material impurities, shell manufacturing intricacies, and molten metal handling, all contributing to the formation of porosity in casting.

The genesis of porosity in casting is multifactorial, often stemming from interactions between materials, processes, and environmental conditions. A holistic understanding requires dissecting each potential source, from raw material contaminants to gas entrapment during solidification. In the following sections, I will systematically analyze these factors, supported by thermodynamic principles and empirical data. The integration of tables and formulas will help summarize key relationships and guidelines, aiming to provide a robust framework for mitigating porosity in casting. Moreover, the repeated emphasis on “porosity in casting” throughout this text underscores its centrality to quality assurance in investment casting operations.

One of the primary contributors to porosity in casting is the quality of raw materials used in the process. Both metal charges and refractory materials can introduce gases or reactive substances that evolve during pouring and solidification, leading to void formation. Metal charges, often comprising scrap or recycled materials, may be contaminated with rust, oil, or moisture. During melting in induction furnaces, these contaminants decompose, releasing gases such as hydrogen and oxygen that dissolve into the molten metal. For instance, rust (iron oxide) can react at high temperatures, contributing to gas generation. The dissolution of hydrogen in steel is particularly critical, as it follows Sieverts’ law, where solubility is proportional to the square root of the partial pressure:

$$ [H] = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}} $$

Here, $[H]$ represents the concentration of dissolved hydrogen, $K_H$ is the equilibrium constant dependent on temperature, and $P_{H_2}$ is the partial pressure of hydrogen. As the metal cools and solidifies, the solubility drops sharply, causing supersaturation and the nucleation of hydrogen bubbles, which manifest as porosity in casting. Similarly, oxygen can react with carbon in the melt to form carbon monoxide, leading to boiling effects and “honeycomb” porosity. To quantify the risk, the gas content in raw materials should be minimized through pre-treatment, such as shot blasting or drying. The table below summarizes common contaminants and their effects on porosity in casting:

| Contaminant Type | Source | Gas Evolved | Impact on Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rust (FeO, Fe₂O₃) | Metal scrap | H₂, O₂ | Increases dissolved gases, leading to bubble formation during cooling. |

| Oil and Grease | Machined parts | Hydrocarbons (CₓHᵧ) | Decomposes to H₂ and CO, causing pinhole porosity. |

| Moisture | Storage conditions | H₂O vapor | Reacts with molten metal to produce H₂, exacerbating porosity. |

| Refractory Impurities | Clay or sand mixes | CO₂, H₂O | Decomposes at high temperatures, generating gas pockets in the mold. |

Refractory materials, such as silica sand and binders, also play a crucial role in inducing porosity in casting. Impurities like calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) can be inadvertently mixed into refractories. When the shell mold is heated during pouring, CaCO₃ decomposes at temperatures above 800°C according to the reaction:

$$ \text{CaCO}_3 \rightarrow \text{CaO} + \text{CO}_2 \uparrow $$

The released CO₂ gas can infiltrate the molten metal, creating gas pockets that result in porosity in casting. Strict quality control in material handling and storage is essential to prevent such cross-contamination. Additionally, the binder system itself—water glass—can contribute if not properly processed. Water glass contains sodium silicate, which may retain moisture or react under heat, further amplifying gas evolution.

Beyond raw materials, the shell manufacturing process is a critical stage where porosity in casting can originate. The construction of the ceramic shell involves multiple steps: coating, stuccoing, drying, dewaxing, and firing. Each step harbors potential pitfalls. Residual pattern material, often wax or polymer, is a common culprit. Incomplete dewaxing leaves carbonaceous residues that, during shell firing or metal pouring, undergo pyrolysis or oxidation reactions. For example, at high temperatures, residual wax can react with atmospheric oxygen or metal oxides:

$$ \text{C}_x\text{H}_y + \text{O}_2 \rightarrow \text{CO}_2 + \text{H}_2\text{O} $$

These gaseous products become trapped at the metal-mold interface, leading to subsurface porosity in casting. Similarly, moisture retention in the shell, whether from incomplete drying or hygroscopic absorption, poses a significant risk. Water molecules can dissociate at pouring temperatures, releasing hydrogen that dissolves into the metal. The reaction is facilitated by the high-temperature environment:

$$ \text{H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow 2[H] + [O] $$

To mitigate these issues, optimal dewaxing parameters—such as steam or flash firing—and controlled drying environments are imperative. The table below outlines key shell-related factors and their association with porosity in casting:

| Shell Process Factor | Description | Consequence for Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Dewaxing | Residual pattern material in shell | Gas evolution from carbon/hydrogen combustion, causing pinholes or blowholes. |

| Inadequate Drying | High moisture content before firing | Steam generation during pouring, leading to gas entrapment and mold erosion. |

| Poor Firing Practice | Insufficient temperature or time | Retained volatiles and incomplete binder burnout, increasing gas pressure. |

| “Fuzz” Formation | Salt migration on shell surface | Localized gas emission from sodium compounds, creating fine porosity. |

Shell firing, or baking, is particularly pivotal in preventing porosity in casting. Water glass-based shells undergo complex physico-chemical transformations during firing, including dehydration, crystal phase changes, and binder decomposition. For instance, sodium silicate decomposes to sodium oxide and silica, while clay components like kaolinite lose structural water. Inadequate firing—typically below 800°C—results in incomplete reactions, leaving behind volatile compounds that vaporize upon metal contact. Proper firing should reach temperatures around 850–900°C with sufficient soaking time (e.g., 2 hours) to ensure a white or pinkish shell color, indicating thorough burnout. Under-fired shells appear gray and are prone to gas evolution, causing not only porosity in casting but also mold cracking or metal penetration.

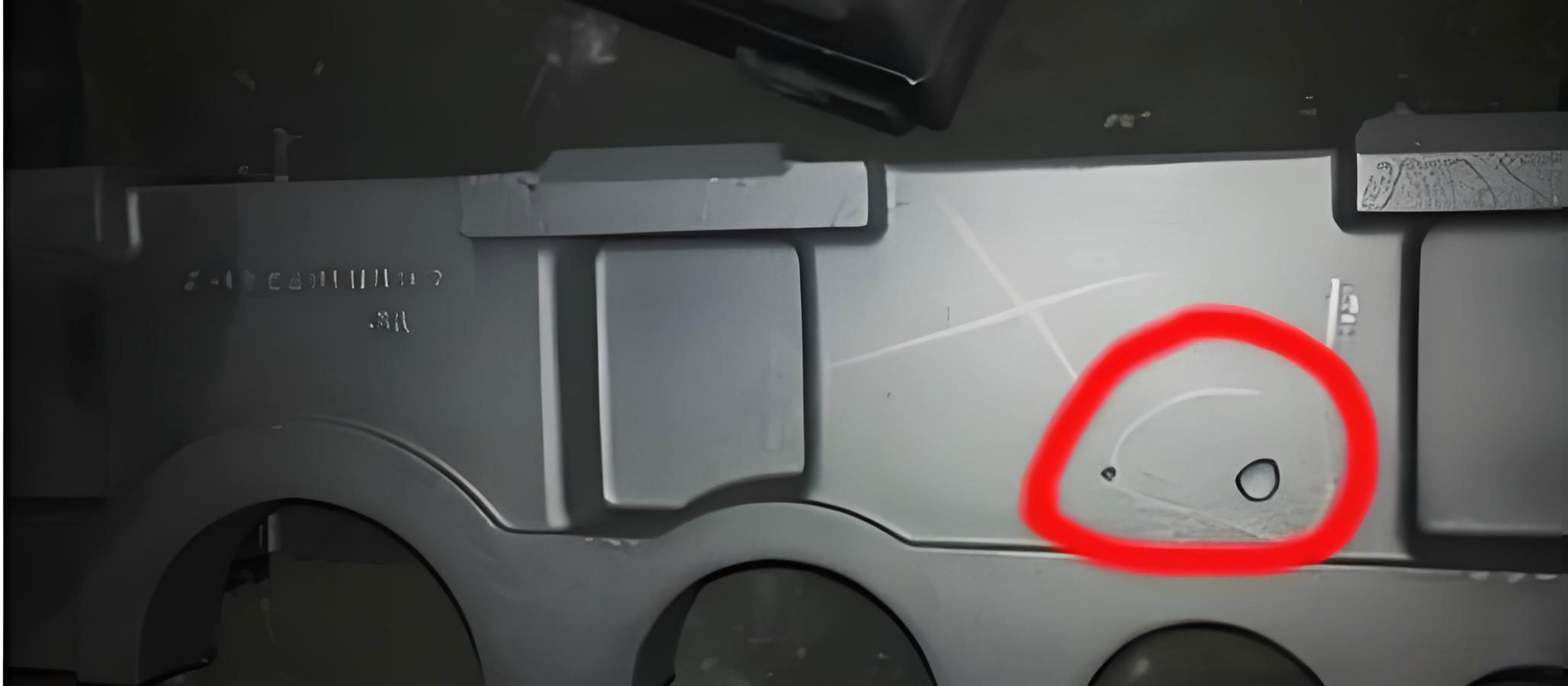

A peculiar phenomenon known as “fuzz” or “salt bloom” on shell surfaces also contributes to porosity in casting. This efflorescence results from the migration of sodium salts (e.g., NaCl, Na₂CO₃) as moisture evaporates during drying. Chemical analysis reveals high sodium chloride content, which has a melting point of 801°C and boils at 1413°C. During pouring, these salt particles vaporize, releasing gas that forms fine, scattered porosity in the casting. Controlling ambient humidity and limiting shell storage time to under 24 hours before firing can reduce fuzz formation. Moreover, optimizing the binder composition to minimize sodium content is beneficial.

Moving to molten metal handling, gas dissolution and purification are central to controlling porosity in casting. Investment casting often employs medium-frequency induction furnaces for melting, which can inadvertently introduce atmospheric gases into the melt. Hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen are the primary culprits, with their solubility governed by temperature and partial pressure. The dissolution process for diatomic gases follows the square-root law, as mentioned earlier. For nitrogen, a similar relationship holds:

$$ [N] = K_N \sqrt{P_{N_2}} $$

Here, $[N]$ is dissolved nitrogen concentration, $K_N$ is the temperature-dependent constant, and $P_{N_2}$ is nitrogen partial pressure. Since solubility increases with temperature, rapid cooling during solidification leads to gas rejection and bubble formation, directly causing porosity in casting. To combat this, melt purification through degassing and deoxidation is essential. Conventional methods include slag formation, temperature control, and the addition of deoxidizers like aluminum, silicon, or manganese. However, a more potent approach involves rare earth elements, which exhibit strong affinity for oxygen and other gases.

Rare earth elements (e.g., cerium, lanthanum) are powerful deoxidizers and desulfurizers. Their effectiveness stems from the highly negative Gibbs free energy of oxide formation, which decreases with increasing temperature, as illustrated in the Ellingham diagram. The standard Gibbs free energy change for rare earth oxide formation can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta G^\circ = \Delta H^\circ – T\Delta S^\circ $$

Where $\Delta G^\circ$ is the standard free energy change, $\Delta H^\circ$ is enthalpy change, $T$ is temperature, and $\Delta S^\circ$ is entropy change. For instance, the reaction for cerium oxidation is:

$$ 2\text{Ce} + 3[O] \rightarrow \text{Ce}_2\text{O}_3 $$

This reaction has a large negative $\Delta G^\circ$, making it thermodynamically favorable. In practice, adding about 0.1–0.2 wt% rare earth elements to the melt can reduce oxygen content from over 100 ppm to below 20 ppm, significantly lowering the risk of porosity in casting. Rare earths also modify inclusions, rendering them harmless. However, excessive addition may lead to brittle intermetallic phases, so dosage must be optimized. The following table compares deoxidation methods and their impact on porosity in casting:

| Deoxidation Method | Mechanism | Efficacy in Reducing Porosity in Casting | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (Al) | Forms Al₂O₃ inclusions | Moderate; may leave residual gases if not fully reacted. | Common but can cause alumina clusters. |

| Silicon (Si) | Forms SiO₂ | Moderate; less effective at low temperatures. | Often used with other deoxidizers. |

| Rare Earths (RE) | Form stable RE oxides and sulfides | High; reduces oxygen and hydrogen simultaneously. | Requires careful dosage to avoid embrittlement. |

| Vacuum Degassing | Physical removal of dissolved gases | High; but equipment-intensive. | Effective for hydrogen and nitrogen. |

The role of rare earths extends beyond deoxidation; they also mitigate hydrogen-induced porosity in casting by forming stable hydrides or altering gas nucleation sites. The interaction between rare earths and hydrogen can be described by equilibrium constants, though practical trials show marked improvements in gas reduction. Additionally, rare earths enhance fluidity and feeding characteristics, indirectly reducing shrinkage porosity, which often coexists with gas porosity. It is crucial to integrate rare earth addition with proper melt handling—for example, adding them after aluminum treatment to prevent premature oxidation.

Another aspect of porosity in casting relates to reactional gases from alloying elements. In steel melts, carbon-oxygen reactions can produce CO bubbles if deoxidation is incomplete. The reaction is:

$$ [C] + [O] \rightarrow \text{CO} \uparrow $$

This is particularly problematic in oxidizing conditions, leading to a boiling effect and macroporosity. The equilibrium constant $K_{CO}$ for this reaction depends on temperature and composition. Maintaining a balanced carbon-to-oxygen ratio through controlled deoxidation is key. Furthermore, nitrogen can react with elements like titanium or aluminum to form nitrides, which may nucleate porosity if gas supersaturation occurs. The solubility product for nitride formation is given by:

$$ [N][\text{Ti}] = K_{\text{TiN}} $$

Where $[\text{Ti}]$ is titanium concentration and $K_{\text{TiN}}$ is the equilibrium product. Monitoring alloy chemistry and using inhibitors can help manage such reactions.

To synthesize the prevention strategies for porosity in casting, a comprehensive approach must address all stages of the investment casting process. Starting with raw material selection, only clean, dry, and low-impurity charges should be used. Pre-treatment processes like shot blasting or thermal drying are advisable. For refractories, strict segregation and quality checks prevent cross-contamination. In shell making, optimize dewaxing by ensuring complete pattern removal through controlled heating cycles. Drying should occur in environments with regulated humidity (ideally below 60% RH) to minimize moisture retention. Firing must achieve temperatures of at least 850°C with adequate soak time to burn out organics and dehydrate the binder. Shell storage should be brief to avoid moisture pickup and salt migration.

In melting and pouring, adopt a dual strategy of physical and chemical gas removal. Use inert gas purging or vacuum degassing to extract dissolved hydrogen and nitrogen. Implement deoxidation with rare earth elements, adding them in conjunction with aluminum for synergistic effects. The recommended sequence is: melt under a protective atmosphere, add aluminum for preliminary deoxidation, then introduce rare earths (e.g., mischmetal) at 0.15 wt% of the melt weight, followed by a brief holding period for homogenization. Pour at moderate temperatures to avoid excessive gas solubility, and ensure the shell is hot (above 500°C) to reduce thermal shock and gas condensation. The following formula summarizes the critical parameters for minimizing porosity in casting:

$$ P_{\text{porosity}} \propto \frac{[G]_{\text{initial}} \cdot T_{\text{pour}} \cdot t_{\text{solidification}}}{K_{\text{degassing}} \cdot Q_{\text{shell}}} $$

Here, $P_{\text{porosity}}$ represents the propensity for porosity formation, $[G]_{\text{initial}}$ is initial gas content in the melt, $T_{\text{pour}}$ is pouring temperature, $t_{\text{solidification}}$ is solidification time, $K_{\text{degassing}}$ is degassing efficiency, and $Q_{\text{shell}}$ is shell quality factor (incorporating dryness and firing). Minimizing the numerator and maximizing the denominator reduces porosity in casting.

In conclusion, porosity in casting is a multifaceted defect that can be systematically addressed through meticulous control over materials, processes, and metallurgy. The analysis reveals that gas sources originate from raw material impurities, shell manufacturing flaws, and molten metal gas dissolution. By implementing stringent material management, optimized shell protocols, and advanced deoxidation techniques like rare earth addition, foundries can significantly reduce the incidence of porosity in casting. Continuous monitoring and adaptation to specific production conditions are essential, as even minor deviations can reintroduce gas-related defects. Ultimately, a holistic quality system that prioritizes gas prevention will enhance yield and component performance, solidifying investment casting’s role in precision manufacturing. The repeated focus on “porosity in casting” throughout this discussion highlights its persistent challenge and the need for integrated solutions.