The relentless drive towards automation and larger-scale operations in the metallurgical industry, particularly in zinc electrowinning, has placed unprecedented demands on critical components. The aluminum cathode plate crossbeam, a primary load-bearing and conductive element, is at the forefront of this challenge. Traditional manufacturing methods, primarily based on welding multiple pieces together, are increasingly revealing their limitations. These include high labor intensity, variable quality dependent on operator skill, and inherent defects such as incomplete fusion. These welding flaws manifest as severe issues in service: structural failures during mechanical stripping, poor conductivity leading to inefficient zinc deposition or re-dissolution, and ultimately, increased operational costs and safety hazards.

While alternatives like gravity-cast integrated hanger ear-crossbeams exist, they often suffer from poor surface finish, cold shuts, and inadequate stiffness. This context has propelled the development of integrated crossbeams manufactured via high-pressure die casting. This process promises superior integrity, consistency, and performance. However, producing a sound, large length-to-diameter ratio casting like a cathode crossbeam (often exceeding 1 meter in length with complex, thin sections) via die casting is fraught with a pervasive enemy: porosity in casting.

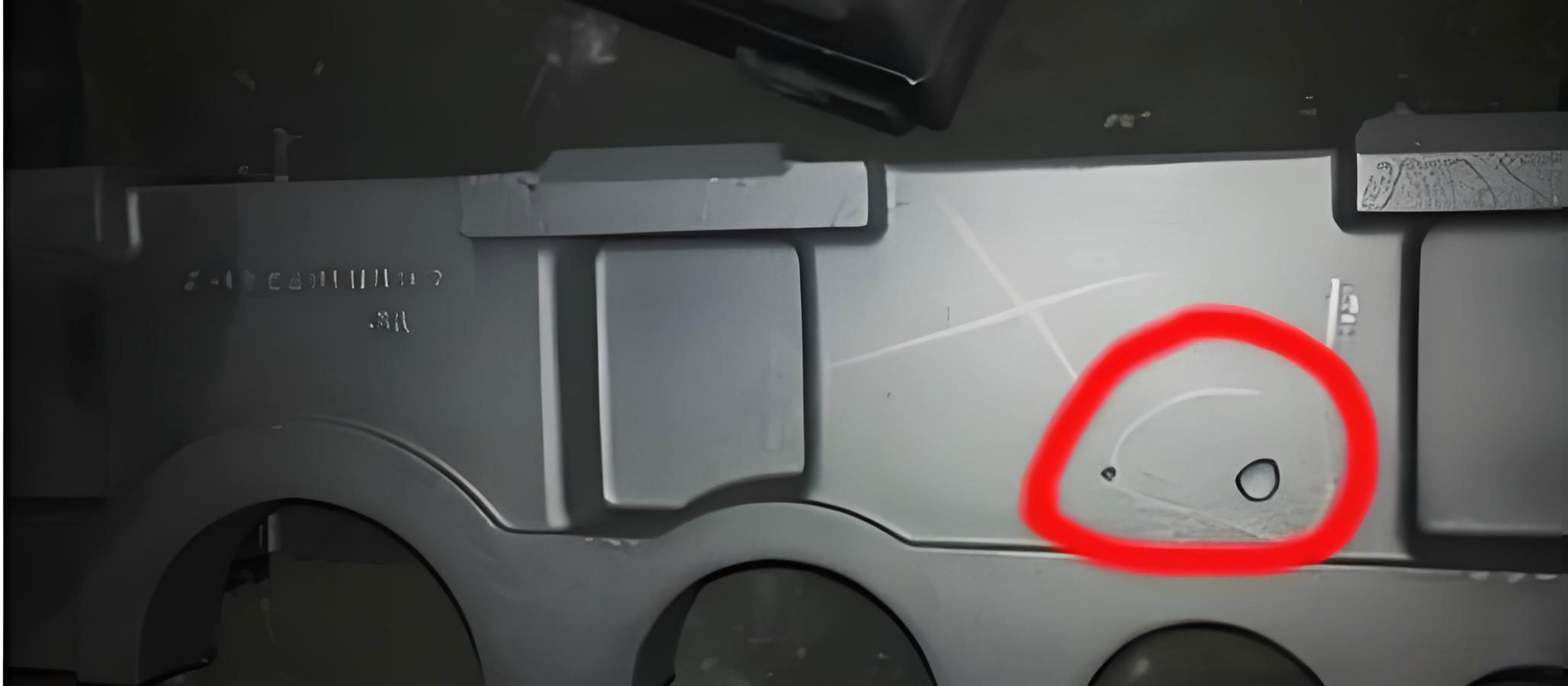

The visual above typifies the challenge of porosity in casting. In die casting, molten metal is injected into a steel mold at high velocity and under intense pressure, solidifying rapidly. This very nature of the process makes it exceptionally vulnerable to gas entrapment. The resultant voids, or pores, critically degrade mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, and pressure tightness. For a conductive crossbeam operating in a corrosive electrolytic bath, even minor subsurface porosity in casting can be a nucleation site for corrosion cracking and a source of increased electrical resistance.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Porosity Formation in Die Casting

To effectively combat porosity in casting, one must first understand its primary sources. In the high-pressure die casting of large, complex components, gas porosity originates from four principal avenues:

- Entrapped Mold Cavity Air: This is often the most significant source of large, irregular pores. If the air within the mold cavity cannot escape faster than the incoming molten metal fills the space, it becomes compressed and trapped. For a large aspect ratio crossbeam with long flow paths and multiple branches, ensuring complete venting is exceptionally challenging. The gas is compressed by the advancing metal front and is often forced into isolated pockets or the last regions to fill.

- Gas from Lubricant/Die Coatings: Die lubricants or release agents, typically water-based, are sprayed onto the hot mold surface. If not fully evaporated, the residual water flashes into steam upon contact with the molten aluminum, creating high-pressure vapor bubbles that become entrapped in the solidifying metal.

- Gas Dissolved in the Molten Metal: Molten aluminum, especially, has a high affinity for hydrogen. The solubility of hydrogen in liquid aluminum is significantly higher than in solid aluminum. This relationship is described by Sieverts’ Law:

$$C_{H} = K_{H} \sqrt{P_{H_{2}}}$$

where $C_{H}$ is the concentration of dissolved hydrogen, $K_{H}$ is the equilibrium constant, and $P_{H_{2}}$ is the partial pressure of hydrogen. During rapid solidification in die casting, the drastic drop in solubility forces the hydrogen to precipitate out as microscopic bubbles. Under the high applied pressure, these bubbles may be compressed to a very small size but remain as a diffuse network of micro-porosity in casting, severely impacting ductility and fatigue strength. - Gas Entrained During Injection (Turbulence): The high-speed injection phase (phase 2 of the shot profile) is critical. If the initial slow phase does not properly position the metal in the shot sleeve, or if the transition to high speed is too abrupt, the metal flow can become turbulent. This turbulence folds air from the shot sleeve or the gate area into the melt stream, creating finely dispersed gas porosity. The phenomena can be related to the Reynolds number ($Re$), which predicts flow regime:

$$Re = \frac{\rho v D}{\mu}$$

where $\rho$ is density, $v$ is velocity, $D$ is hydraulic diameter, and $\mu$ is dynamic viscosity. Exceeding a critical $Re$ leads to turbulent flow and air entrainment.

The following table summarizes the characteristics and primary causes of porosity in casting in this context:

| Porosity Type | Typical Size & Location | Primary Source | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Gas Pores | Large, irregular, often in last-to-fill areas or thick sections. | Entrapped mold cavity air. | Inadequate venting, poor gating design, excessive fill speed. |

| Micro-Porosity (Pinholes) | Very small, diffuse, often uniformly distributed. | Hydrogen precipitation during solidification. | High hydrogen content in melt, high solidification rate. |

| Entrained Air Porosity | Small, spherical, often aligned with flow direction. | Turbulence during injection folding air into melt. | Poor shot profile, low shot sleeve fill percentage, high gate velocity. |

| Blister Porosity | Subsurface pores expanding during painting or heating. | Combination of hydrogen micro-porosity and surface sealing. | High hydrogen content, high casting pressure compressing pores near surface. |

Systematic Countermeasures to Minimize Porosity

Addressing porosity in casting for a large aspect ratio crossbeam requires a holistic, system-wide approach targeting each source. The following strategies were developed and implemented to transform a porous, defective casting into a structurally and electrically sound component.

1. Mold Design Optimization for Enhanced Venting

The original mold design, while functional, failed to account for the complex, long-flow-length nature of the crossbeam. Dead zones and long flow paths impeded air escape. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation software (e.g., ProCAST, MAGMASOFT) became an indispensable tool. By simulating the melt flow and air displacement, multiple scenarios were analyzed.

- Gating and Runner System: The gate location and cross-sectional area were optimized to promote laminar, directional filling. A larger gate area was used to reduce metal velocity at the point of entry into the cavity, thereby reducing turbulence and air entrainment.

- Strategic Venting: Beyond standard vents at the end of flow paths, additional overflow wells and venting channels were incorporated at critical locations:

- At the junction of multiple flow fronts (potential air traps).

- Along the sides of the long beam sections.

- In areas identified by simulation as last-to-fill or having low pressure.

Vent thickness was carefully calibrated—thick enough to allow air escape but thin enough to freeze before molten metal escapes, preventing flash.

2. Molten Metal Treatment and Process Control

Controlling the hydrogen content in the molten aluminum is paramount to minimizing micro-porosity in casting.

- Degassing/Refining: A rotary impeller degassing system using high-purity nitrogen ($N_2$) or argon ($Ar$) was employed. An inert gas is bubbled through the melt. According to Sieverts’ Law, the partial pressure of hydrogen in the bubbles is effectively zero ($P_{H_2} \approx 0$), creating a strong chemical potential gradient. Dissolved hydrogen diffuses into the bubbles and is carried to the surface. The process efficiency can be modeled by considering diffusion kinetics and bubble surface area. A common refining flux was also used to help separate and remove oxides and other inclusions that can nucleate pores.

- Minimized Holding Time: The holding furnace for the die casting machine was managed to minimize the melt’s exposure time. Prolonged holding, especially at high temperatures, increases hydrogen pickup from atmospheric moisture. The temperature was tightly controlled within a optimal range (e.g., 670-680°C) to maintain fluidity while minimizing gas solubility and oxidation.

3. Critical Process Parameter Optimization

The shot profile and related parameters are the final and most direct control over porosity in casting.

| Parameter | Initial Setting | Optimized Setting | Rationale & Effect on Porosity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shot Sleeve Fill Percentage | ~50% | 60% – 70% | A higher fill percentage reduces the volume of air in the shot sleeve that must be compressed and pushed ahead of the plunger. This directly reduces the amount of air available for entrainment. Too high a fill percentage risks spilling. |

| Phase 1 (Slow Shot) Speed | Empirically set | Optimized via simulation | The slow shot must position the metal just before the gate without turbulence. Proper setting prevents air being pushed into the cavity early. |

| Phase 2 (Fast Shot) Speed | 6 m/s | 4 m/s | Reducing the fill velocity lowers the metal’s kinetic energy and Reynolds number, promoting more laminar flow. This minimizes turbulence-induced air entrainment and gives cavity air more time to escape through vents. |

| Fill Time | ~0.10 s | ~0.15 s | Increased fill time is a direct consequence of lower fast-shot speed. It provides a crucial extra window for air evacuation from the complex, long cavity. |

| Intensification Pressure | 60 MPa | Maintained or slightly increased | High intensification pressure is applied after the cavity is filled. It compresses any remaining gas pores to a smaller size and feeds shrinkage during solidification, reducing both gas and shrinkage porosity in casting. The pressure must be high enough to be effective but within machine and mold limits. |

| Die Temperature | 180 ± 25°C | Stable 180 ± 5°C | A stable, sufficiently high die temperature ensures metal fluidity, allows complete filling of thin sections, and can slightly slow solidification, aiding gas escape. Large fluctuations cause variable quality. |

The interplay of these parameters is crucial. For instance, the reduction in fill speed (v) directly increases fill time (t) for a given volume (V), as shown by the simplified relation:

$$ V = A_{gate} \cdot v \cdot t $$

where $A_{gate}$ is the gate area. This intentional trade-off sacrifices raw cycle time for quality by directly attacking the root cause of venting-limited and turbulence-induced porosity in casting.

Performance Validation of the Optimized Die Cast Crossbeam

The effectiveness of the integrated countermeasures against porosity in casting was validated through rigorous mechanical, electrical, and operational testing.

1. Structural Integrity and Mechanical Properties

Destructive testing on sampled castings from the optimized process revealed a significant reduction in visible and macroscopic porosity. The cross-sections showed dense, homogeneous material with excellent metallurgical bonding at the copper-aluminum composite interface for the conductive head.

Load testing was performed to quantify mechanical performance:

- Three-Point Bend Test (Beam Stiffness): The integrated crossbeam demonstrated a calculated overall bending strength of 73.33 MPa.

- Hanger Ear Load Capacity: The critical hanger ears, which bear the entire weight during mechanical stripping, were tested to failure.

- Open-Type Hanger Ear: Effective load capacity: 844 kg.

- Closed-Type Hanger Ear: Effective load capacity: 1894 kg.

These values far exceed typical operational loads, providing a significant safety margin and demonstrating the integrity achieved by minimizing porosity in casting.

2. Electrical Conductivity and Operational Efficiency

Electrical resistance is a hypersensitive indicator of internal defects like porosity in casting, as voids interrupt the conductive path. The resistance of the optimized crossbeam was measured and compared to its theoretical minimum value.

The theoretical resistance $R_{theory}$ for a homogeneous conductor is given by:

$$ R_{theory} = \rho \frac{L}{A} $$

where $\rho$ is the resistivity of the aluminum alloy (approximately 2.85 x 10-8 Ω·m), $L$ is the conductive length (~1 m), and $A$ is the average cross-sectional area.

For the crossbeam design:

$$ R_{theory} = 2.85 \times 10^{-8} \cdot \frac{1.0}{0.07 \cdot 0.014} \approx 29.08 \mu\Omega $$

Measured values on production crossbeams ranged from $\Omega_{min} = 29.21 \mu\Omega$ to $\Omega_{max} = 30.29 \mu\Omega$.

The average measured resistivity was 100.4% of the theoretical value. This near-perfect correlation indicates an extremely low volume of porosity in casting, as significant voids would have increased the resistance measurably above the theoretical baseline.

The ultimate proof was in-plant performance. A batch of 1,000 die-cast integrated crossbeams was monitored alongside traditional welded crossbeams over several months. Temperature at the conductive head—a direct indicator of resistive heating—was recorded.

| Crossbeam Type | Min. Temp. (°C) | Max. Temp. (°C) | Avg. Temp. (°C) | Median Temp. (°C) | % of Units > 50°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Die-Cast Integrated | 36 | 56 | 44.7 | 42 | ~15% |

| Traditional Welded | 36 | 63 | 47.9 | 44 | ~34% |

The results are conclusive. The die-cast crossbeams ran, on average, 3.2°C cooler than their welded counterparts. More strikingly, the incidence of “hot” crossbeams (temperature > 50°C) was reduced by over 55% in the die-cast version. This lower, more consistent operating temperature directly translates to lower energy consumption (reduced cell voltage), enhanced operational safety, and longer component life, all stemming from the superior integrity and reduced porosity in casting.

Conclusion

The successful production of high-integrity, large aspect ratio aluminum crossbeams via high-pressure die casting is a testament to a systematic, science-based approach to defeating porosity in casting. The battle is won not by a single silver bullet, but by a coordinated campaign on multiple fronts:

- Intelligent Mold Design: Leveraging flow simulation to design gating and, most critically, comprehensive venting strategies tailored to the part’s geometry to ensure air evacuation keeps pace with metal fill.

- Melt Quality Control: Implementing rigorous degassing and holding practices to minimize the hydrogen content dissolved in the molten aluminum, thereby reducing the source of micro-porosity in casting.

- Precision Process Control: Meticulously optimizing the shot profile—specifically increasing shot sleeve fill percentage, reducing fill speed, and maintaining high intensification pressure—to minimize air entrainment and compress any residual porosity.

The outcome is a component that transcends the limitations of welded assemblies. It exhibits superior and more predictable mechanical strength, electrical conductivity approaching the theoretical limit of the alloy, and demonstrably better in-service performance with lower operating temperatures. This integrated die-casting solution provides a reliable, high-performance, and cost-effective answer to the evolving demands of modern hydrometallurgy, fundamentally by conquering the pervasive challenge of porosity in casting.