In my investigation into the persistent challenge of porosity in casting, particularly within aluminum alloy components, I focused on a critical yet often nuanced factor: the solidification cooling rate. This study was driven by the understanding that while hydrogen content is the primary determinant for pore formation, the thermal conditions under which the alloy solidifies profoundly influence the final size, morphology, distribution, and quantity of these defects. High-integrity castings for demanding applications cannot tolerate such inconsistencies. Therefore, I systematically designed and executed an experiment to isolate and examine the effect of varying cooling rates, achieved through different molding methods and section thicknesses, on the characteristics of porosity in casting.

Aluminum alloys are paramount in modern manufacturing due to their excellent specific strength, corrosion resistance, and castability. However, the quest for flawless components is frequently hindered by internal defects. Among these, gas porosity and shrinkage porosity are predominant, often coalescing into complex pore structures that degrade mechanical properties, pressure tightness, and fatigue life. The formation of porosity in casting is fundamentally linked to the rejection of dissolved hydrogen during solidification and the inability to feed volumetric shrinkage. The kinetic interplay between hydrogen diffusion, nucleation of pores, and the advancing solidification front is governed by the local thermal history. A slower cooling rate extends the time available for hydrogen diffusion and pore growth, while a faster rate can trap hydrogen in solution or limit pore size. This research delves into this interplay, providing a detailed empirical analysis.

1. Experimental Methodology and Materials

The core objective was to generate a controlled matrix of cooling conditions for a common aluminum-silicon alloy. The approach involved manipulating cooling rates via three primary variables: mold material, casting wall thickness, and location within a casting.

1.1. Materials and Equipment

The trials utilized a hypoeutectic Al-Si alloy, akin to A356, with a nominal composition provided in Table 1. Approximately 10 kg of the alloy was melted for each experimental series.

| Si | Mg | Fe | Other Elements | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.5 – 7.5 | 0.25 – 0.45 | < 0.20 | < 0.10 | Balance |

Key equipment included:

- An industrial resistance furnace for melting.

- A rotary degassing unit using argon gas for baseline melt treatment.

- A reduced pressure test (RPT) system to assess initial melt hydrogen content prior to pouring.

- Standard foundry tools for molding and pouring.

1.2. Design of Experiments for Cooling Rate Variation

To create a spectrum of cooling rates, the following experimental conditions were established:

| Variable | Levels | Intended Effect on Cooling Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Mold Material | Green Sand, Resin-Bonded Sand, Permanent Metal Mold (coated), Permanent Metal Mold (uncoated) | Significantly different heat extraction capacities. Uncoated metal mold provides the fastest cooling. |

| Casting Wall Thickness | 5 mm, 10 mm, 20 mm | Within the same mold, thicker sections cool slower due to larger thermal mass. |

| Location within Sample | Edge, Center | In thicker sections, the edge cools faster than the center due to mold wall chilling. |

Simple plate-like patterns were fabricated for the sand molds. The metal molds were constructed from steel plates to form cavities of the specified thicknesses. A ceramic-based coating was applied to one set of metal molds to moderately reduce their chilling power. All metal molds were preheated to approximately 200°C to prevent premature freezing of the metal stream.

1.3. Procedure

The alloy was melted, degassed using the rotary impeller with argon, and then assessed for hydrogen content using the RPT to ensure a consistent starting point for porosity in casting formation studies. The melt was held at a superheat of 730±10°C before being poured into the various prepared molds. After solidification and cooling, the plate castings were extracted. From each plate, a central section was cut. This section was then subdivided into three coupons (top, middle, bottom), with the middle coupon used for analysis to minimize end effects. The analysis surface (mid-thickness cross-section) was meticulously ground, polished, and lightly etched to reveal the porosity in casting without introducing artifacts. The pore networks were then examined and documented using optical microscopy.

2. Results and Analysis: The Cooling Rate Regime

The analysis confirmed a strong and systematic relationship between the solidification cooling rate and all defining characteristics of the resulting porosity in casting.

2.1. Effect of Mold Material (Constant 10mm Section)

For a constant 10 mm wall thickness, the mold material created the most dramatic differences in cooling rate and, consequently, pore structure.

| Mold Type | Estimated Cooling Rate | Porosity Morphology & Distribution | Relative Pore Quantity & Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resin-Bonded Sand | Slowest | Highly irregular, elongated pores. Widely dispersed across the entire section. | Large number, large average size. |

| Green Sand | Slow | Irregular shapes, some rounded. Dispersed distribution. | Large number, large average size, often larger than in resin sand. |

| Coated Metal Mold | Fast | More rounded pores, tendency for localized clusters. | Moderate number, small to moderate size. |

| Uncoated Metal Mold | Fastest | Small, mostly spherical pores. Less clustered than coated metal mold. | Fewest number, smallest average size. |

Interpretation: The very slow cooling in sand molds leads to a long “mushy zone” (past the eutectic temperature $T_E$), enabling substantial hydrogen diffusion and pore growth. The local solidification time $t_f$ is high. Pores form and expand over an extended period, often coalescing and conforming to the complex interdendritic spaces, resulting in irregular shapes. In green sand, an additional source of hydrogen from moisture decomposition exacerbates the total pore volume. The relationship between pore radius $r$ and diffusion time can be conceptually linked by a simplified growth model:

$$ \frac{dr}{dt} \propto D_H \frac{C_l – C_s}{\rho_g} \cdot \frac{1}{r} $$

where $D_H$ is hydrogen diffusivity, $C_l$ and $C_s$ are hydrogen concentrations in liquid and solid at the interface, and $\rho_g$ is gas density. Longer $t_f$ allows for greater integrated growth ($r$ increases).

In contrast, the rapid cooling of the uncoated metal mold results in a short $t_f$ and a steep thermal gradient $G$. This promotes planar or cellular solidification front, leaving little time for hydrogen rejection and diffusion. Most hydrogen remains in solid solution (supersaturated), and the few pores that nucleate have limited growth opportunity, remaining small and spherical. The coated metal mold presents an intermediate case, reducing $G$ slightly and allowing slightly more time for pore development, leading to clustering.

2.2. Effect of Wall Thickness (Constant Mold: Green Sand)

Varying the wall thickness within the same insulating sand mold provided a clear gradient of cooling rates.

| Wall Thickness | Relative Cooling Rate | Predominant Solidification Mode | Porosity Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mm | Fastest (for sand) | Predominantly skin-forming (directional). | Pores are relatively few, smaller, and more localized (e.g., at the thermal center). |

| 10 mm | Intermediate | Mixed skin-forming and mushy. | Increased pore count and size compared to 5mm. More dispersed distribution. |

| 20 mm | Slowest | Fully mushy (pasty) solidification. | Highest pore count and largest size. Pores are highly irregular and uniformly distributed throughout the cross-section. |

Interpretation: The thin (5mm) section solidifies relatively quickly even in sand. The thermal gradient is steeper, favoring directional solidification from the walls. Porosity, largely driven by shrinkage now as hydrogen has less time to segregate, concentrates in the last region to freeze. The thick (20mm) section experiences severe conditions for porosity in casting formation. The enormous thermal mass leads to a very low $G$ and long $t_f$. A vast, undercooled mushy zone exists where dendrites grow in all directions. Hydrogen is extensively rejected into the interdendritic liquid, and the long freezing time allows both significant hydrogen diffusion and the development of substantial shrinkage cavities. Hydrogen pores easily nucleate and expand within these shrinkage cavities, leading to large, complex, and widely distributed pores. The solidification time can be approximated by the Chvorinov’s rule:

$$ t_f = B \cdot \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where $V/A$ is the volume-to-surface area ratio (modulus), $B$ is a mold constant, and $n$ is an exponent (~2). The 20mm plate has a much higher modulus than the 5mm plate, leading to a quadratically longer solidification time, directly enabling more severe porosity in casting.

2.3. Effect of Location Within a Thick Section (Uncoated Metal Mold, 20mm)

Even under the fast cooling of a metal mold, a thick section exhibits a thermal gradient from surface to center.

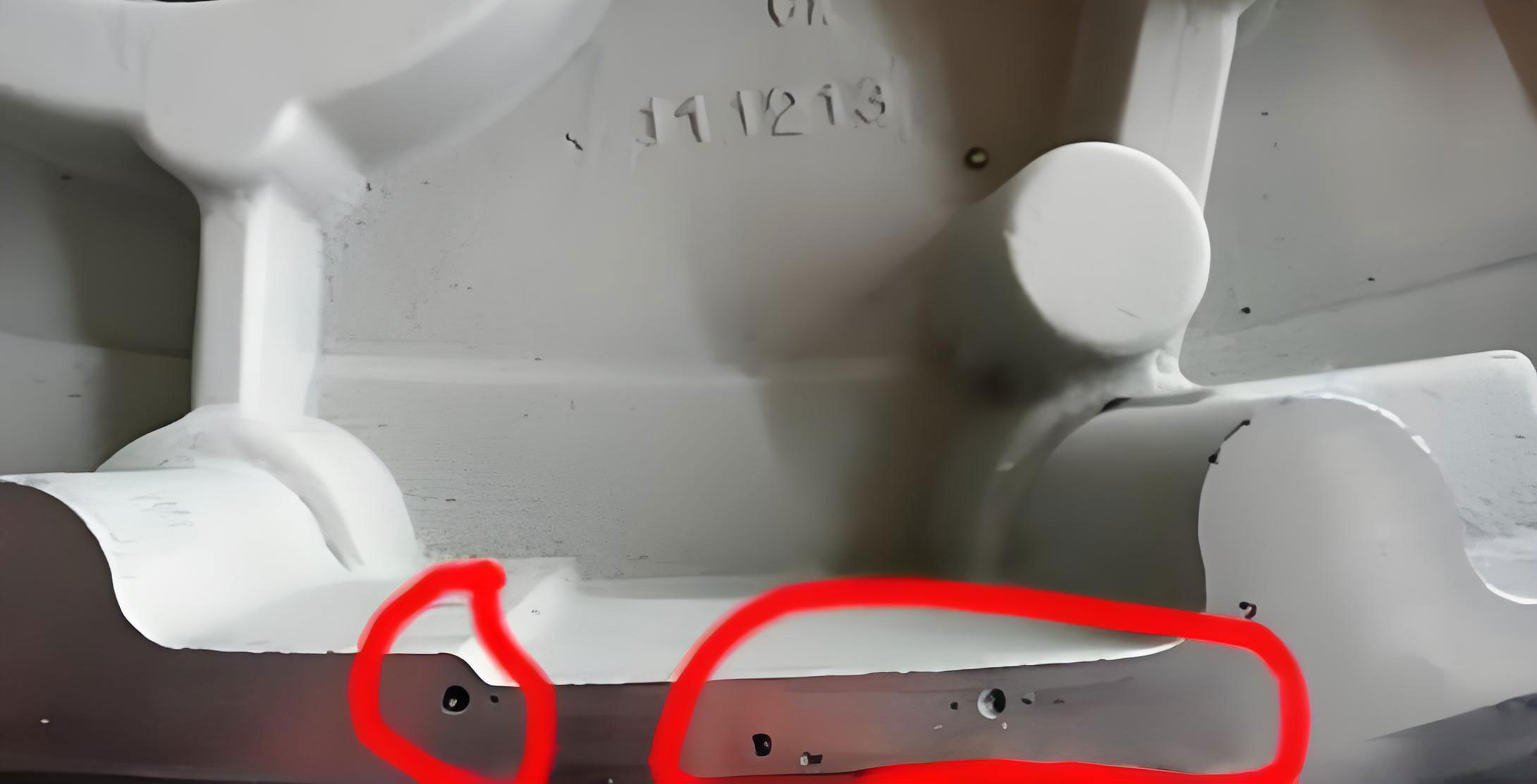

Observation: In the 20mm thick casting from the uncoated metal mold, the region near the mold wall (edge) exhibited few, very small, and spherical pores. In stark contrast, the thermal center of the same sample contained a significantly higher density of pores. These central pores were also larger and more irregular in shape compared to those at the edge.

Interpretation: This result powerfully demonstrates the role of local thermal history. The mold wall provides intense chilling, creating a zone of very rapid solidification at the edge where hydrogen is trapped. The center, however, is thermally insulated by the surrounding metal. Its cooling rate, while still faster than in a sand mold of equivalent thickness, is the slowest within this casting. This local reduction in cooling rate at the center extends the time for solidification, allowing for greater solute (hydrogen) redistribution, pore nucleation, and growth. It effectively creates a “micro-scale” version of the wall thickness effect within a single sample. The local thermal gradient $G$ and growth velocity $v$ determine the morphology of the solid-liquid interface and the resulting porosity in casting. The ratio $G/v$ is much higher at the edge than at the center.

3. Discussion: Mechanisms Linking Cooling Rate to Porosity

The observed trends can be synthesized into a coherent mechanistic framework centered on the concepts of solidification mode, hydrogen diffusion, and pore nucleation/growth kinetics.

3.1. Solidification Mode Transition

The cooling rate directly controls whether solidification proceeds as planar, columnar dendritic, or equiaxed dendritic (mushy). The transition is governed by the extent of constitutional undercooling ahead of the interface. The criterion for the onset of constitutional undercooling is:

$$ \frac{G}{v} \leq \frac{m_L C_0 (1-k_0)}{D_L k_0} $$

where $m_L$ is the liquidus slope, $C_0$ is the initial alloy composition, $k_0$ is the partition coefficient, and $D_L$ is the solute diffusivity in liquid. A low cooling rate (low $G$ and/or high local solidification time $t_f$) promotes a low $G/v$ ratio, easily satisfying this inequality and leading to a mushy zone. This mushy zone is the primary site for the development of porosity in casting. The extended dendritic network provides plentiful nucleation sites and traps interdendritic liquid rich in rejected hydrogen.

3.2. Hydrogen Redistribution and Pore Stability

During solidification, hydrogen is rejected from the solidifying phase ($k_0 < 1$ for H in Al). The concentration in the remaining liquid $C_L$ increases according to the Scheil equation approximation:

$$ C_L = C_0 \cdot (1 – f_s)^{(k_0-1)} $$

where $f_s$ is the solid fraction. When $C_L$ exceeds the solubility limit at the local pressure, a pore can nucleate. The critical radius for a pore nucleus $r^*$ is given by:

$$ r^* = \frac{2 \gamma}{\Delta P} $$

where $\gamma$ is the gas-liquid surface tension and $\Delta P$ is the pressure difference driving nucleation (supersaturation pressure minus external pressure). Slower cooling increases the time during which $C_L$ is high and may lower the local pressure due to inadequate feeding, reducing $r^*$ and making pore nucleation easier. Once nucleated, pore growth is diffusion-limited. The growth rate depends on the supersaturation and the diffusion length, both of which are time-dependent variables strongly influenced by the cooling rate.

3.3. Integrated Model for Porosity Prediction

A comprehensive view considers the interplay of thermal, solutal, and pressure fields. The Niyama criterion, originally for shrinkage, highlights the role of thermal parameters:

$$ \frac{G}{\sqrt{\dot{T}}} $$

where $\dot{T}$ is the cooling rate. A low Niyama value indicates a risk region for shrinkage porosity, which often acts as a host for gas porosity. For direct gas porosity, a simplified criterion for pore formation can be conceptualized as a function of local solidification time and hydrogen content:

$$ \text{Pore Formation Risk} \propto [H]_0 \cdot t_f^\alpha \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{\beta}{G}\right) $$

where $[H]_0$ is initial hydrogen content, $t_f$ is local solidification time, $G$ is thermal gradient, and $\alpha$, $\beta$ are material constants. This formalism captures my experimental observations: high hydrogen, long solidification time (thick sections, insulating molds), and low thermal gradient all exponentially increase the risk and severity of porosity in casting.

4. Conclusions

This systematic study unequivocally establishes solidification cooling rate as a master variable controlling the manifestation of porosity in casting in aluminum alloys. The following definitive conclusions were drawn:

- Morphology and Distribution: Rapid cooling (e.g., uncoated permanent mold) produces a low amount of porosity in casting, characterized by small, spherical pores that may be clustered. Slow cooling (e.g., sand molds) results in a high density of large, irregularly shaped pores that are widely dispersed throughout the casting section.

- Mold Material Interaction: The choice of mold material is a primary lever for controlling cooling rate. However, secondary effects are critical: green sand can introduce additional hydrogen from moisture, amplifying total porosity, while resin sand, despite its slow cooling, may allow some hydrogen escape during its extended solidification, slightly moderating pore volume.

- Section Sensitivity: For a given mold, increased wall thickness dramatically increases the severity of porosity in casting due to a quadratic increase in solidification time and a shift towards a mushy solidification mode. This effect is so potent that even in a fast-cooling metal mold, the thermal center of a thick section can exhibit porosity characteristics akin to a slower-cooling environment.

- Underlying Mechanism: The observed effects are governed by the cooling rate’s control over the local solidification time $t_f$ and thermal gradient $G$. These parameters dictate the solidification mode (planar vs. mushy), the extent of hydrogen redistribution, the time available for pore nucleation and diffusion-limited growth, and the interaction with shrinkage feeding. The formation of porosity in casting is thus a kinetic competition between solidification advancement and gas pore evolution.

Therefore, to minimize and control porosity in casting, process design must prioritize strategies that achieve a sufficiently high cooling rate for the given section thickness. This can involve selecting more conductive mold materials (metal molds, chills), optimizing mold coatings, or designing castings with more uniform and thinner sections where possible. This work provides a foundational empirical and mechanistic framework for making such engineering decisions aimed at enhancing the internal soundness and reliability of aluminum alloy castings.