Based on my experimental research into the factors affecting porosity in aluminum alloy castings, this article synthesizes the key findings and underlying principles. The study systematically investigated the roles of melt hydrogen content, solidification rate, alloy crystallization temperature interval, and external pressure. The goal was to elucidate the formation mechanisms of porosity in casting to provide a theoretical foundation for process optimization and quality prediction.

Introduction: Significance and Objectives

The prevalence of porosity in casting represents a major challenge in producing high-integrity aluminum components. These defects act as stress concentrators, severely degrading mechanical properties such as tensile strength, fatigue resistance, and fracture toughness, while also impairing pressure tightness and corrosion resistance. As demand grows for lightweight, high-performance castings in sectors like aerospace and automotive, controlling porosity in casting becomes paramount. The primary cause is hydrogen, whose solubility in liquid aluminum is approximately 20 times greater than in the solid state. During solidification, rejected hydrogen can form bubbles that become trapped, leading to various forms of porosity in casting. Therefore, understanding the precise factors governing pore nucleation and growth is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies. This work aimed to dissect these influencing factors through controlled experiments, linking empirical observations to solidification theory.

Fundamental Principles

1. Sources of Gas and Inclusions

Hydrogen is the primary gas dissolved in aluminum melts. Its main source is the reaction between molten aluminum and water vapor from the atmosphere, humid tools, or charge materials:

$$2Al_{(l)} + 3H_2O_{(g)} \rightarrow Al_2O_{3(s)} + 6[H]$$

This reaction simultaneously introduces both hydrogen atoms ([H]) and oxide inclusions (Al2O3). Inclusions further exacerbate the problem by acting as favored nucleation sites for hydrogen bubbles, thereby promoting porosity in casting.

2. Principles of Hydrogen Absorption and Removal

The solubility of hydrogen follows Sievert’s Law, where the concentration in the melt is proportional to the square root of the hydrogen partial pressure in the surrounding atmosphere:

$$[H] = K \sqrt{P_{H_2}}$$

Here, [H] is the dissolved hydrogen concentration, K is the solubility constant (temperature-dependent), and PH2 is the equilibrium hydrogen partial pressure. During solidification, the local hydrogen concentration in the remaining liquid can become highly supersaturated, driving pore formation.

The kinetic process of degassing, such as by inert gas purging, can be described by a mass transfer equation. The change in bulk hydrogen concentration Cm over time is given by:

$$\frac{dC_m}{dt} = -\frac{A}{V}K(C_m – C_{ms})$$

where A/V is the specific surface area of bubbles, K is the mass transfer coefficient, and Cms is the hydrogen concentration at the bubble-liquid interface. Effective degassing requires maximizing A/V, minimizing bubble size, and increasing bubble residence time in the melt.

3. Modes and Directions of Solidification

The solidification mode, determined by the alloy’s crystallization temperature range (ΔTc) and the thermal gradient (G), critically influences the morphology of porosity in casting.

- Planar/Layer-by-Layer Solidification: Occurs when ΔTc is narrow and G is steep. The solid-liquid interface is relatively smooth, providing short and open paths for liquid feeding and gas escape. This mode tends to lead to concentrated shrinkage cavities and smaller, rounder gas pores.

- Pastry/Mushy Volume Solidification: Occurs when ΔTc is wide and G is shallow. A broad mushy zone filled with dendritic networks develops early. Liquid becomes isolated in inter-dendritic regions, hindering both feeding and gas evolution. This promotes dispersed micro-porosity in casting, often irregular in shape and combined with shrinkage (forming “shrinkage-gas pores”).

The transition can be approximated by the ratio ΔTc/G.

4. Mechanism of Pore Formation

The formation of porosity in casting is fundamentally linked to solute redistribution during solidification. Applying the Tiller-Chalmers model for a stagnant boundary layer, the hydrogen concentration in the liquid ahead of the solid interface, CL, is:

$$C_L = C_0 \left[ 1 + \frac{1-k}{k} \exp\left(-\frac{vx}{D}\right) \right]$$

where C0 is the initial melt hydrogen content, k is the partition coefficient for hydrogen, v is the solidification velocity, x is the distance from the interface, and D is the hydrogen diffusion coefficient in the liquid.

A pore can nucleate when CL exceeds the saturation concentration, CS. The width of this supersaturated zone, Δx, and its duration, Δt, are crucial for pore formation:

$$\Delta x = \frac{D}{v} \ln\left[\frac{1-k}{k} \left( \frac{C_S}{C_0} – 1 \right)\right]$$

$$\Delta t = \frac{\Delta x}{v} = \frac{D}{v^2} \ln\left[\frac{1-k}{k} \left( \frac{C_S}{C_0} – 1 \right)\right]$$

These equations show that a lower solidification rate (v) increases both Δx and Δt, enhancing the opportunity for pore nucleation and growth, thus increasing the severity of porosity in casting.

The condition for a bubble to nucleate and grow against external pressure is:

$$P_{H_2} > P_{atm} + \rho g h + \frac{2\sigma}{r}$$

where PH2 is the internal hydrogen pressure, Patm is atmospheric pressure, ρgh is the metallostatic head, σ is surface tension, and r is the bubble radius. Increasing the external pressure on the melt (e.g., in low-pressure casting) directly raises the right-hand side of this inequality, making pore formation more difficult.

5. Low-Pressure Casting Principle

Low-pressure casting involves applying a controlled gas pressure (typically 0.1-0.3 MPa) onto the surface of molten metal in a sealed furnace, forcing it up a riser tube to fill a mold. This method offers smoother filling and allows the pressure to be maintained during solidification, which suppresses pore formation and improves feeding.

Experimental Investigation of Pressure and Hydrogen Content

1. Experimental Conditions and Methodology

The primary alloy used was ZL105 (Al-Si-Cu-Mg). Melt hydrogen content was monitored and controlled using a density measurement technique. Three melt states were prepared: unrefined (high hydrogen), refined (low hydrogen), and intermediate (“furnace bottom” melt). Castings were produced using a low-pressure casting machine under three different applied pressures: 0 MPa (atmospheric), 0.1 MPa, and 0.27 MPa. Specimens from different casting sections (body and thin fins) were sectioned, ground, polished, and examined under a stereomicroscope to characterize the porosity in casting.

2. The Influence of Applied Pressure

The applied pressure during low-pressure casting was found to be a dominant factor in reducing porosity in casting. The results are summarized conceptually below.

| Factor | Condition | Effect on Porosity in Casting | Governing Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applied Pressure | Atmospheric (0 MPa) | High pore count and size | $$P_{H_2} > P_{ext} + \rho g h + \frac{2\sigma}{r}$$ Higher Pext raises the threshold for bubble nucleation and growth. |

| Low Pressure (0.1 MPa) | Moderate reduction in pore count and size | ||

| Higher Pressure (0.27 MPa) | Significant reduction; pores are fewer and smaller |

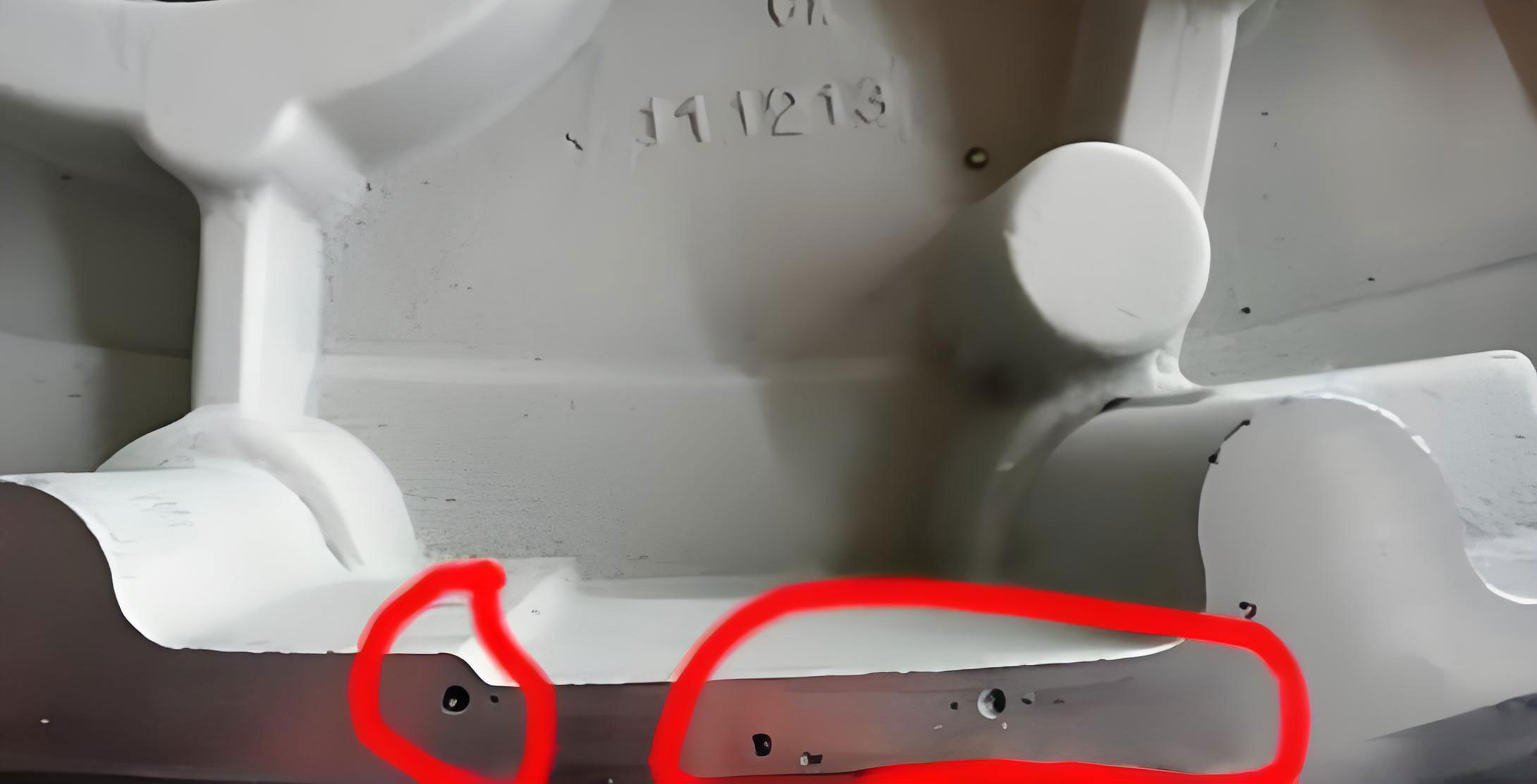

At 0.27 MPa, the body of the casting showed remarkably few pores. However, some larger shrinkage-gas pores were observed in sections adjacent to chills, where rapid solidification impaired feeding. Thin fin sections were particularly sensitive; insufficient pressure led to mistuns and surface-connected pores, likely from mold gas invasion. This highlights that while pressure is highly effective, adequate filling pressure and mold drying remain critical to prevent specific types of porosity in casting.

3. The Influence of Melt Hydrogen Content

As expected, hydrogen content was the primary driver for pore formation. This was true under both atmospheric and pressurized conditions.

| Melt Condition | Relative Hydrogen Content | Porosity Characteristics at 0 MPa | Porosity Characteristics at 0.27 MPa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrefined | High | Extensive, large, irregular pores throughout | Numerous pores, but significantly reduced vs. 0 MPa case |

| Refined | Low | Few, small, round pores | Very few, very fine pores |

| Furnace Bottom | Medium | Moderate pore count and size | Few pores, slightly larger than refined state |

The results clearly demonstrate that for a given pressure, higher hydrogen content leads to more severe porosity in casting. Furthermore, applying pressure significantly improves casting density even with higher hydrogen melts, though it cannot fully compensate for poor degassing. The combined action of low hydrogen and high applied pressure yields the most sound castings.

Experimental Investigation of Solidification Rate and Alloy Type

1. Influence of Solidification Rate

Solidification rate was varied by changing the mold material (metal, resin sand, green sand) and casting section thickness for a given alloy (ZL102).

| Mold Type | Cooling Rate | Solidification Mode Trend | Porosity in Casting Observed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Mold | Fast | Towards layer-by-layer | Fewest pores, small and round |

| Green Sand Mold | Medium | Intermediate | More, larger, irregular pores |

| Resin Sand Mold | Slow | Towards mushy | Most pores, largest size, irregular shape |

Furthermore, within a single thick casting (40mm) made in resin sand, the porosity in casting varied by location:

- Bottom (fastest cooling): Fewer, more localized pores.

- Middle: Increased pore count and size.

- Top (slowest cooling, last to feed): Highest pore count and size, uniformly distributed.

These observations align perfectly with the theory expressed in the Δx and Δt equations. A slower solidification rate (lower v) increases the width and lifetime of the hydrogen-enriched zone, providing greater opportunity for pore nucleation and coalescence, thereby intensifying porosity in casting.

2. Influence of Crystallization Temperature Interval

Two alloys with distinctly different solidification ranges were compared: near-eutectic ZL102 (narrow ΔTc) and ZL105 (wider ΔTc).

| Alloy | Crystallization Interval | Dominant Solidification Mode | Characteristic Porosity Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZL102 | Narrow | Layer-by-layer | Rounder, more distinct pores. Feeding is more effective, so pores are more purely gas-driven. |

| ZL105 | Wider | Mushy/Volume | Irregular, often angular “shrinkage-gas” pores. Early dendrite coherency isolates liquid pools, combining shrinkage and gas effects. |

For the same section thickness and mold type, ZL105 consistently exhibited a greater amount and larger size of porosity in casting compared to ZL102. The wider freezing range promotes the formation of a broad mushy zone where interdendritic feeding is restricted and hydrogen is efficiently trapped, leading to the characteristic irregular pore morphology.

Conclusion

This comprehensive study confirms that porosity in casting is a complex phenomenon governed by interdependent factors. The key conclusions are:

- Applied Pressure: Increasing the metallostatic pressure during solidification, as in low-pressure casting, is a highly effective means of suppressing pore nucleation and growth, leading to denser castings. However, it must be sufficient to ensure complete filling, especially of thin sections.

- Melt Hydrogen Content: This is the most critical factor. Lowering the initial hydrogen concentration directly reduces the driving force for pore formation and is the first step in controlling porosity in casting.

- Solidification Rate: Faster cooling reduces the time and spatial extent for hydrogen segregation and bubble growth, thereby reducing the severity of porosity in casting. This validates the predictions of the solute redistribution model.

- Alloy Solidification Range: Alloys with a narrow crystallization interval tend towards layer solidification, producing rounder, more distinct gas pores. Alloys with a wide interval solidify in a mushy mode, leading to irregular, combined shrinkage-gas pores that are more detrimental. The solidification mode fundamentally shapes the morphology of porosity in casting.

Ultimately, controlling porosity in casting requires an integrated approach: rigorous melt degassing to minimize hydrogen, process design (choice of molding material, use of chills) to achieve favorable solidification rates and gradients, and, where possible, the application of pressure during solidification. Understanding these principles allows for the scientific prediction and prevention of this pervasive defect.