The production of high-integrity, load-bearing components is a cornerstone of heavy machinery manufacturing. Among these, the axle housing, or steering axle shell, is a critical structural element. This component functions as the central mounting point for the wheel assemblies and must withstand complex multidirectional forces including bending moments, torsional loads, and impact stresses during service. The transition from fabricated to monolithic shell castings offers significant advantages in terms of structural integrity, reduced manufacturing steps, and overall cost-effectiveness for such parts. This article details the comprehensive process, from initial design to final validation, for producing a ductile iron steering axle housing, leveraging numerical simulation as a core tool for optimization.

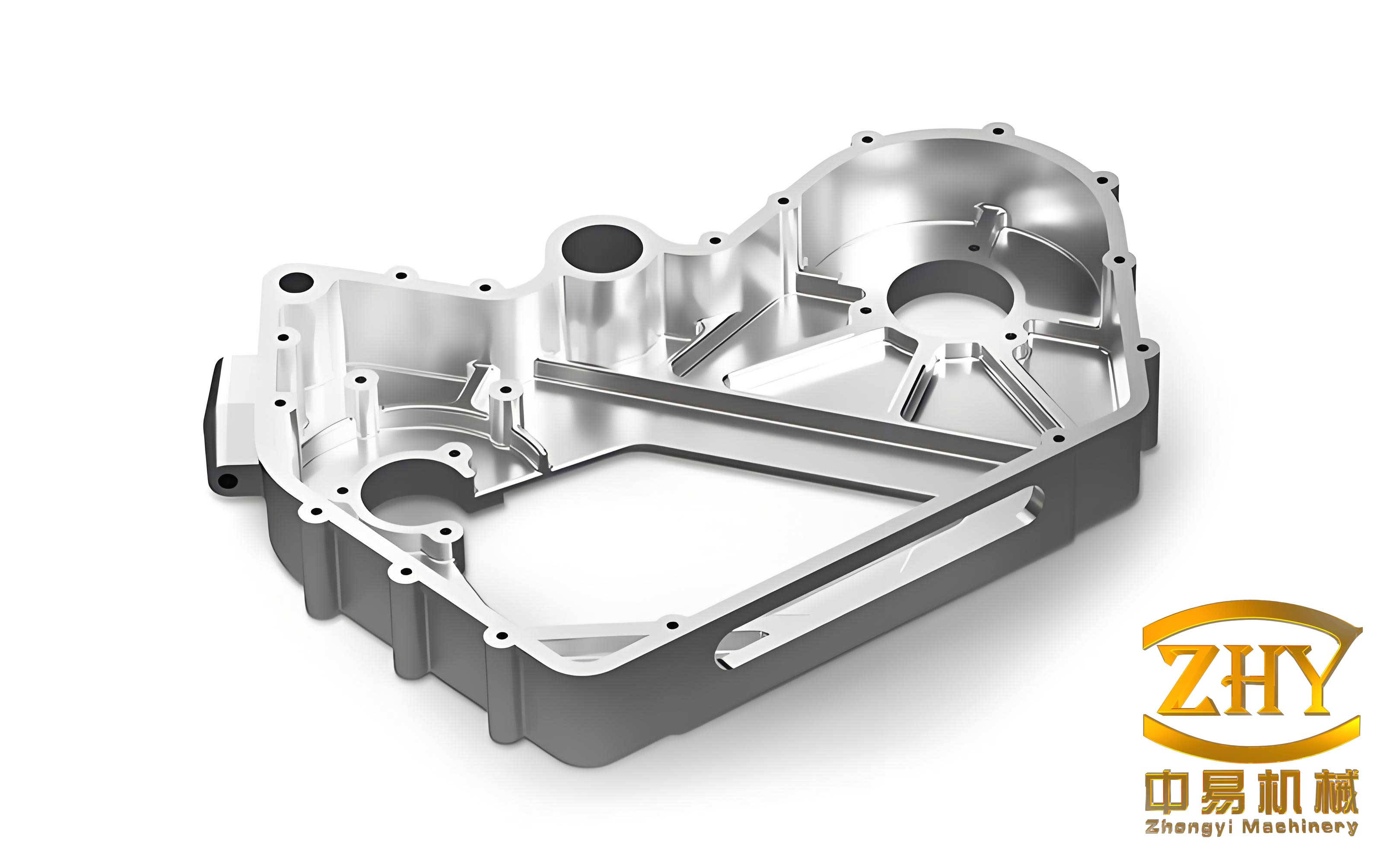

The specific shell casting under consideration is designed for a forklift steering axle. Its primary function is to house the steering hydraulic cylinder and provide mounting interfaces for the steering knuckles at both ends. The geometry is complex, featuring a central cavity, several external mounting bosses, and pronounced asymmetry. Key characteristics of the component are summarized below:

- Mass: 70 kg

- Overall Dimensions: 834 mm (L) x 228 mm (W) x 348 mm (H)

- Wall Thickness: Variable, with an average of 25.26 mm, a maximum of 63.11 mm, and a minimum of 15 mm.

- Material: Ductile Iron QT450-10 (EN-GJS-450-10).

The material choice is paramount. QT450-10 offers an excellent combination of strength, ductility, and castability, which is essential for safety-critical shell castings. Its mechanical properties derive from the spherical graphite morphology achieved through inoculation and spheroidization treatments. The required chemical composition and mechanical properties are specified in the following tables.

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cu | Mg | RE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.6-3.9 | 2.0-2.5 | 0.25-0.45 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.02 | 0.1-0.15 | 0.035-0.060 | ≤0.02 |

| Tensile Strength, Rm (MPa) | Yield Strength, Rp0.2 (MPa) | Elongation, A (%) | Hardness (HBW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 450 | ≥ 310 | ≥ 10 | 160 – 210 |

Initial Casting Process Design

The design of the casting process for these shell castings begins with fundamental decisions regarding the molding method, pouring position, and parting line. Given the component’s size, complexity, and the typical batch size, green sand molding was deemed less optimal due to potential accuracy issues. Instead, the furan resin no-bake sand process was selected. This binder system provides excellent dimensional accuracy, high strength, good collapsibility, and is well-suited for low-to-medium volume production of high-quality iron castings.

Two primary schemes for the pouring position and parting surface were evaluated. The first scheme oriented the heavy knuckle-mounting arms vertically, with a horizontal parting line splitting the casting between cope and drag. This required a large, complex core for the internal cavity. The second scheme oriented the knuckle arms horizontally, utilizing a combined horizontal and contoured parting surface, placing most of the casting in the drag for better dimensional stability. Although this second scheme required several loose pieces for undercut features, it offered superior surface finish on critical machined faces and minimized the risk of mold shift. Therefore, the second scheme was adopted.

The gating system is a critical element for achieving sound shell castings. A bottom-gated, naturally pressurized (semi-choked) system was designed to ensure smooth, non-turbulent filling. The choke is at the sprue base, with the total runner cross-sectional area being the largest. The designed area ratios were: Sprue : Runner : Ingate = 1.2 : 1.5 : 1. The key parameters were calculated using hydraulic principles.

The total poured weight (including gating and feeders) was estimated at 187 kg, assuming a casting yield of approximately 65-70%. The theoretical pouring time $\tau$ (s) is often estimated empirically based on casting weight:

$$\tau = S \sqrt{G_L}$$

where $S$ is a coefficient dependent on section thickness (taken as 2.2 for medium sections) and $G_L$ is the total poured mass in kg. For our 187 kg system:

$$\tau = 2.2 \times \sqrt{187} \approx 30 \text{ seconds}$$

Accounting for the fluidity of ductile iron, this time is often reduced by 20-30%, leading to a target pouring time of 20 seconds.

The cross-sectional area of the ingates $A_{ingate}$ is calculated using the orifice flow formula:

$$A_{ingate} = \frac{G_L}{\rho \cdot \mu \cdot \tau \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot g \cdot h_p}}$$

where:

- $\rho$ = melt density (7100 kg/m³ for iron)

- $\mu$ = discharge coefficient (typically 0.55-0.65 for metal, 0.6 used)

- $g$ = gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s²)

- $h_p$ = effective metallostatic pressure head at the ingate (m)

The effective pressure head $h_p$ is derived from the average pressure head $H_p$ in the mold cavity and the gating ratio:

$$H_p = H_0 – \frac{P^2}{2C}$$

where $H_0$ is the height of the sprue (0.30 m), $P$ is the height of the casting above the ingates (0.21 m), and $C$ is the total casting height (0.345 m). Thus:

$$H_p = 0.30 – \frac{(0.21)^2}{2 \times 0.345} \approx 0.236 \text{ m}$$

$$h_p = \frac{k_2^2}{1 + k_1^2 + k_2^2} \cdot H_p$$

With $k_1$ (Sprue:Runner area ratio) = 0.8 and $k_2$ (Sprue:Ingate area ratio) = 1.2:

$$h_p = \frac{1.2^2}{1 + 0.8^2 + 1.2^2} \times 0.236 \approx 0.110 \text{ m}$$

Substituting back to find the ingate area:

$$A_{ingate} = \frac{187}{7100 \times 0.6 \times 20 \times \sqrt{2 \times 9.8 \times 0.110}} \approx 15.0 \times 10^{-4} \text{ m}^2 = 15.0 \text{ cm}^2$$

Consequently:

$$A_{sprue} = 1.2 \times A_{ingate} = 18.0 \text{ cm}^2$$

$$A_{runner} = 1.5 \times A_{ingate} = 22.5 \text{ cm}^2$$

To distribute flow evenly to the two shell castings in the mold, a tapered runner system was designed. The initial runner cross-section was 22 cm², reducing to 15.5 cm² and finally 8.1 cm² after each ingate branch to maintain pressure. Six ingates (3 per casting) were used, each with an area of 2.5 cm², placed at the bottom of the drag to enable uphill filling. The sprue base included a well to reduce turbulence.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Pouring Mass | $G_L$ | 187 kg | Including gating/feeders |

| Target Pouring Time | $\tau$ | 20 s | Adjusted for ductile iron |

| Sprue Cross-Sectional Area | $A_{sprue}$ | 18.0 cm² | Choke area |

| Main Runner Cross-Sectional Area | $A_{runner}$ | 22.5 / 15.5 / 8.1 cm² | Tapered design |

| Total Ingate Area | $A_{ingate}$ | 15.0 cm² | – |

| Number of Ingates | – | 6 | 2.5 cm² each |

Numerical Simulation of the Initial Process

With the initial process designed, numerical simulation software (e.g., ProCAST, MAGMASOFT) was employed to virtually evaluate the filling and solidification behavior. This step is indispensable for modern foundries producing complex shell castings, as it predicts defects before expensive tooling is made. The 3D model of the mold assembly was meshed, and appropriate boundary conditions were set: furan resin sand properties, an initial mold temperature of 25°C, a pouring temperature of 1350°C, and an interfacial heat transfer coefficient of 500 W/(m²·K).

The filling simulation confirmed a smooth, laminar fill pattern with a total fill time of approximately 19 seconds, aligning with the design target. No significant surface turbulence or air entrapment was predicted. The focus then shifted to solidification analysis, which is critical for ductile iron due to its mushy freezing characteristics and expansion during graphite precipitation.

The solidification simulation revealed problematic areas. The main defect predictions were shrinkage porosity located in the isolated, thick sections of the knuckle-mounting arms on both sides of the central housing. Additionally, a surface depression (sink) was predicted on the top conical boss. Analysis of solidification iso-time plots and temperature gradient maps provided the root cause.

The central hub and top boss, despite being the heaviest sections, solidified last (around 1300s) but did not show shrinkage porosity. This is attributed to the phenomenon of “self-feeding” or “feedability” in ductile iron, where the expansion force from graphite formation ($\approx 4.2$% volume increase) can compensate for the liquid and solidification contraction, provided the mold is rigid enough. The resin sand mold provided this necessary rigidity.

However, the knuckle arms, while connected to the thermal mass of the central hub initially, developed isolated liquid pockets. Analysis of the solid fraction progression showed that the connection path between the arm and the central hub solidified prematurely (at ~828s), leaving an isolated liquid zone within the arm itself. This isolated zone, now lacking a liquid feed path and subject to faster cooling in its thinner regions, experienced insufficient graphite expansion pressure to overcome shrinkage, leading to microporosity.

The sink defect on the conical boss is a direct result of liquid contraction without adequate compensation. As the highest point in the casting, it acted as a “hot spot” and was the last point to be fed. The liquid contraction occurring throughout the casting as it cooled from pouring temperature to solidus was fed by metal from this boss, causing it to draw inwards. The solidification sequence can be described by analyzing the thermal gradient $\vec{\nabla}T$ and the local solidification time $t_f$. Regions with low thermal gradient and long $t_f$ are prone to shrinkage if not properly fed.

$$ t_f = \frac{T_{pour} – T_{solidus}}{(\partial T/\partial t)_{local}} $$

Where $(\partial T/\partial t)_{local}$ is the local cooling rate.

| Defect Location | Type | Predicted Cause | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knuckle Mounting Arms | Shrinkage Porosity | Formation of isolated liquid zones | Premature isolation from feeding source prevents compensation of shrinkage by graphite expansion. |

| Top Conical Boss | Surface Sink / Depression | Lack of feed metal for liquid contraction | Liquid contraction of the entire casting is fed from the highest point, causing inward draw. |

Process Optimization Based on Simulation

The simulation clearly identified the inadequacies of relying solely on the self-feeding capacity of ductile iron for these particular shell castings. An optimized feeding strategy was required. The principle is to ensure directional solidification towards a dedicated feeder (riser) that can supply liquid metal to compensate for both liquid shrinkage and solidification shrinkage in the isolated regions, while also managing the graphite expansion pressure.

Two types of feeders were designed:

- Top Open Feeders (Sink Heads): Two cylindrical open feeders were placed on either side of the top conical boss. Their primary function is to act as a liquid reservoir to feed the liquid contraction of the entire casting and the solidification shrinkage of the top boss itself. They also serve as vents and heat sinks.

- Side Blind Feeders (Hot Risers): Four side risers were attached to the knuckle arms and other thicker sections. These are designed to remain molten longer than the casting section they are feeding, ensuring a thermal gradient that drives feed metal into the casting to compensate for solidification shrinkage in the now-isolated zones. Their design follows modulus principles.

The feeder neck design is crucial to control the timing of feed metal flow and to allow the feeder to be easily removed. The neck should freeze after the casting section but before the feeder itself to maximize feeding efficiency while allowing break-off. The modulus (Volume/Surface Area ratio) of the feeder $M_f$ should be greater than that of the casting section $M_c$ it feeds. A common rule is:

$$ M_f = 1.1 \times M_c $$

For the knuckle arm section with an approximate modulus $M_c$, the required feeder modulus was calculated, dictating its diameter and height. The feeder volume $V_f$ must also satisfy the required feed metal demand based on the shrinkage of the feeding area $V_c$ and the feeding efficiency of the feeder material $ \varepsilon $ (around 14% for ductile iron in sand molds).

$$ V_f \geq \frac{V_c \cdot \beta}{\varepsilon} $$

where $\beta$ is the volumetric shrinkage of the alloy (for ductile iron, liquid shrinkage is ~2.5%, with net shrinkage dependent on expansion).

For the top open feeders, a necked-down (washburn) design was used to promote early freezing of the neck after the feeder has performed its liquid contraction feeding role, isolating the feeder from the casting pressure during the later expansion phase.

Validation of the Optimized Process

The modified process model, incorporating the designed feeder system, was subjected to a new simulation. The results were markedly improved. The simulation predicted the complete elimination of shrinkage porosity within the shell castings themselves. The feed metal flow vectors showed liquid being drawn from the side risers into the knuckle arms during the critical period of solidification. The top open feeders showed significant draw-down, confirming they were supplying metal to compensate for the bulk liquid contraction, and the sink defect on the conical boss was eliminated. All predicted shrinkage was now contained within the feeder heads, which are removed during cleaning, resulting in sound castings.

| Aspect | Initial Process | Optimized Process |

|---|---|---|

| Shrinkage in Knuckle Arms | Present (Internal Porosity) | Eliminated (Moved to Side Risers) |

| Surface on Top Boss | Sink Defect Predicted | Smooth Surface |

| Solidification Soundness | Unsound in critical sections | 100% Sound Casting Body |

| Casting Yield | ~65-70% (Est.) | Reduced due to feeders, but quality assured. |

The optimized process was translated into production tooling. Molding was performed with furan resin sand. The base iron was melted in a medium-frequency induction furnace, superheated to 1500°C for purification, and then treated with a rare-earth magnesium ferrosilicon alloy for spheroidization followed by inoculation. Pouring was conducted at 1350±10°C.

After shakeout and cleaning, the produced shell castings were fully inspected. Dimensional checks confirmed accuracy. Chemical analysis and mechanical testing on separately cast samples verified compliance with QT450-10 specifications. Most importantly, a sectioning test was performed on a randomly selected casting. Macroscopic examination of the critical sections, including the knuckle arms and the top boss, revealed dense, sound metal with no evidence of shrinkage cavities or porosity, thus physically validating the simulation predictions and the success of the optimization.

| Process Stage | Parameter | Value / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Molding | Method | Furan Resin No-Bake Sand |

| Mold Hardness | > 90 (B Scale) | |

| Cores / Loose Pieces | As per optimized design | |

| Melting & Treatment | Furnace | Medium-Frequency Induction |

| Spheroidizing Agent | RE-Mg-FeSi | |

| Inoculant | Ba-FeSi | |

| Pouring Temperature | 1350 ± 10 °C | |

| Quality Check | Mechanical Test | Separately cast coupons (See Table 2) |

| Integrity Check | Sectioning & Macro-etching |

Conclusion

The successful production of high-integrity ductile iron shell castings for demanding structural applications requires a systematic approach that integrates traditional foundry engineering with advanced simulation tools. For the steering axle housing:

- The initial process design, based on empirical calculations and sound foundry practice for gating and molding, provided a solid foundation.

- Numerical simulation proved invaluable in identifying latent defects—specifically, shrinkage in isolated hot spots and surface sinks—that were not apparent from traditional modulus calculations alone, due to the complex geometry and the unique solidification behavior of ductile iron.

- The optimization strategy, involving a combination of top open feeders for liquid contraction and strategically placed side risers to feed isolated sections, was directly guided by simulation analysis. The design of these feeders followed modulus and volume requirement principles to ensure their efficacy.

- The final validation through both simulation and physical sectioning confirmed that the optimized process reliably produces sound shell castings meeting all quality and performance specifications.

This case study underscores that for complex shell castings, a “right-first-time” approach is achievable. The synergy of fundamental metallurgical knowledge, rigorous process design, and predictive simulation minimizes costly trial-and-error, reduces lead time, and ensures the consistent production of reliable components for critical applications. The methodology presented here provides a robust framework for the design and optimization of casting processes for similar heavy-section, high-duty ductile iron components.