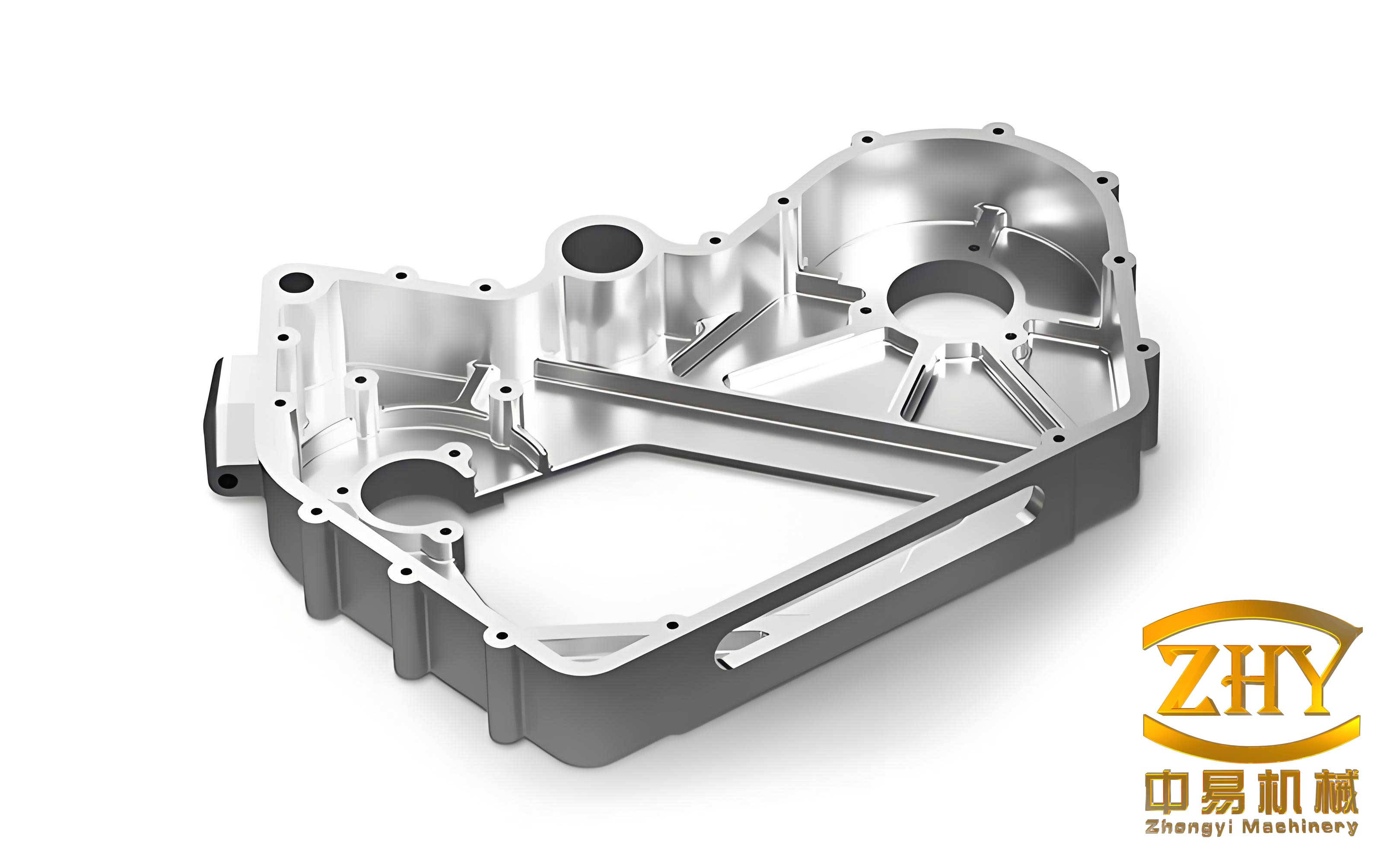

In the competitive foundry industry, rising costs of pig iron have driven many small to medium-sized operations to seek innovative cost-saving measures. One such approach involves utilizing machining scrap iron, primarily in the form of iron chips, as a major charge component for producing high-quality castings. This article details my firsthand experience in adopting a medium frequency furnace to melt iron scrap for manufacturing gearbox casings, a critical application requiring robust mechanical properties. These gearbox casings are essentially shell castings, characterized by their complex geometries and stringent performance criteria. By integrating iron scrap into the melt, we achieved significant cost reductions while maintaining the integrity of the shell castings. The process not only underscores the viability of sustainable practices but also highlights the technical nuances involved in producing reliable shell castings from recycled materials.

The journey began with the challenge of reducing raw material expenses without compromising product quality. Traditional reliance on pig iron was becoming economically untenable. Initially, we experimented with a small cupola furnace for melting. However, its limited height resulted in unstable molten iron temperatures, leading to inconsistent quality in our shell castings. The coke-to-iron ratio was poor, at approximately 1:4.5 to 1:5.0. We then upgraded to a 3 t/h hot-blast cupola with a lined hearth, measuring 600 mm in diameter and 4.5 m in height, equipped with four rows of tuyeres. This improved stability, increased superheating, and achieved a better coke-to-iron ratio of 1:6 to 1:7. Yet, when incorporating low-cost charge materials like iron scrap, the melting rate dropped. Pre-processing scrap into briquettes using binders or slag-forming agents added extra costs, diminishing the savings. We considered dedicated scrap melting furnaces, but their high energy consumption, difficulty in controlling composition, and limited suitability for high-grade iron alloys made them less attractive. After thorough evaluation, we invested in a 1.5-ton medium frequency induction furnace, which proved to be a game-changer for producing shell castings from scrap.

The core of our process lies in meticulous charge composition and control. For gearbox casings—shell castings made of HT250 gray iron—the target chemical composition ranges are critical. We aim for the following weight percentages:

| Element | Target Range (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.2% – 3.6% |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.6% – 2.0% |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.7% – 1.0% |

To achieve this, the typical charge mix consists of 60% iron scrap, 20% returns (such as risers and defective castings), and 20% pig iron. In some batches, we even used up to 90% iron scrap with only 10% returns, minimizing pig iron usage. During charging, we layer pig iron or returns on top of the scrap to facilitate melting and reduce oxidation. Silicon and manganese levels are adjusted using ferrosilicon and ferromanganese additions. Carbon control is particularly crucial when using high scrap ratios. For minor adjustments, adding pig iron suffices; for significant carbon deficit from scrap, we employ carbon raisers. The carbon content can be approximated by the relationship:

$$ C_{final} = C_{charge} + \Delta C_{raiser} – \Delta C_{oxidation} $$

where \( C_{final} \) is the final carbon content, \( C_{charge} \) is the carbon from the charge, \( \Delta C_{raiser} \) is the contribution from carbon raisers, and \( \Delta C_{oxidation} \) accounts for losses during melting. This formula helps in pre-calculating additions to ensure the shell castings meet specifications.

Melting temperature plays a pivotal role in eliminating the genetic effects of charge materials. Iron scrap often contains carbides or graphite clusters that may not fully dissolve, acting as nuclei during solidification and leading to inherited microstructures. Higher superheating temperatures break down these clusters, reducing genetic inheritance. With the medium frequency furnace, we achieve a consistent molten iron temperature of 1560°C, measured using thermocouples. This temperature is significantly higher than that attainable in cupolas, providing better homogenization and improved properties for the shell castings. The superheating effect can be modeled by the Arrhenius-type equation for dissolution kinetics:

$$ k = A e^{-E_a / (RT)} $$

where \( k \) is the dissolution rate constant, \( A \) is the pre-exponential factor, \( E_a \) is the activation energy, \( R \) is the gas constant, and \( T \) is the absolute temperature. Higher \( T \) increases \( k \), promoting complete dissolution of undesired phases.

Furnace control is complemented by rigorous upfront testing. We pour triangular test samples with dimensions 40 mm in height, 20 mm in width, and 130 mm in length. After cooling to a dull red heat, the samples are water-quenched and fractured to examine the chill width. A chill width of around 9 mm indicates suitable composition for pouring the shell castings. This empirical test correlates with carbon equivalent (CE), calculated as:

$$ CE = C + \frac{Si + P}{3} $$

For HT250 shell castings, CE typically ranges from 3.9 to 4.1. The chill width \( w \) can be related to CE through an inverse relationship: \( w \propto \frac{1}{CE} \).

The molding and core-making processes for these shell castings employ green sand techniques. We use bentonite with fine granularity (over 98% passing 200 mesh) at 6–7% by weight, along with 5–6% coal dust to prevent mechanical penetration, reduce subsurface porosity, and enhance surface finish. The sand properties are critical for dimensional accuracy and surface quality of the shell castings. Key parameters include moisture content (controlled at 3–4%), green compressive strength (around 150 kPa), and permeability (approximately 120). These ensure the molds can withstand the metallostatic pressure without deformation.

Casting parameters are optimized for the shell castings. The pouring temperature is maintained between 1360°C and 1380°C. We emphasize fast, smooth, and continuous pouring to avoid cold shuts and slag inclusion. Proper slagging-off is mandatory. The pouring time \( t \) for a given casting volume \( V \) can be estimated using:

$$ t = \frac{V}{A \sqrt{2gh}} $$

where \( A \) is the choke area of the gating system, \( g \) is gravitational acceleration, and \( h \) is the effective metal head. This helps design gating systems for turbulence-free filling of shell castings.

The production outcomes have been highly satisfactory. Mechanical properties evaluated on separately cast test bars (Ø20 mm × 120 mm) consistently meet requirements. The results are summarized below:

| Property | Average Value | Specification for HT250 |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (\( \sigma_b \)) | 240–249 MPa | ≥250 MPa (typical) |

| Hardness (HB) | 210–220 | 180–250 |

Microstructural analysis reveals fine, uniformly distributed graphite flakes with rounded edges, set in a matrix of fine pearlite. This microstructure is ideal for the durability and machinability of shell castings. The graphite morphology can be quantified using parameters like aspect ratio and nodularity, but for flake graphite in these shell castings, we focus on size and distribution. The average graphite length is under 100 μm, contributing to the strength. Daily production averages 300 gearbox casings (shell castings), with a yield rate exceeding 95%, demonstrating process stability.

Safety and operational vigilance are paramount when using medium frequency furnaces with iron scrap. Key considerations include:

- Scrap Preparation: Iron chips contaminated with oils or cutting fluids must be dried via centrifugation, baking, or sun-drying to prevent explosive vaporization when added to molten metal.

- Bridging and Shell Formation: Proper charging sequences and periodic stirring avoid material bridges and cold spots that could lead to operational halts.

- Furnace Safety Systems: The induction furnace must have a closed-loop cooling water system with temperature and flow monitoring/alarm, emergency cooling water backup, robust steel框架结构, and comprehensive electrical protections (e.g., overcurrent, leakage).

These measures ensure safe production of shell castings while adapting to environmental standards.

To further illustrate the process parameters, here is a comprehensive table of key operational data:

| Parameter | Value or Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Furnace Capacity | 1.5 tons | Medium frequency induction type |

| Melting Temperature | 1560°C | Measured with thermocouple |

| Charge Composition | 60% scrap, 20% returns, 20% pig iron | Variable based on scrap availability |

| Carbon Raiser Addition | 0.1–0.5% of charge weight | For carbon adjustment |

| Pouring Temperature | 1360–1380°C | For shell castings |

| Molding Sand Moisture | 3–4% | Green sand with bentonite and coal dust |

| Chill Width (Test Sample) | 9 ± 1 mm | Quality control indicator |

| Daily Production Volume | 300 pieces | Of gearbox casings (shell castings) |

| Yield Rate | >95% | Reflecting process efficiency |

The economic impact is substantial. By using iron scrap as the primary charge, we reduced raw material costs by approximately 40%, translating to savings of about 600 USD per ton of castings produced. This cost-effectiveness does not come at the expense of quality; the shell castings exhibit excellent performance in field applications. The medium frequency furnace offers superior temperature control, reduced environmental emissions compared to cupolas, and flexibility in charge makeup—all beneficial for sustainable foundry operations.

In conclusion, the adoption of a medium frequency furnace for melting iron scrap has revolutionized our production of shell castings, specifically gearbox casings. This approach aligns with circular economy principles by valorizing waste materials. Key success factors include precise composition control, adequate superheating to mitigate genetic effects, rigorous process monitoring, and stringent safety protocols. The resulting shell castings meet mechanical and microstructural standards at a lower cost, enhancing competitiveness. Future work may explore optimizing scrap blends for other grades of shell castings or integrating advanced sensors for real-time quality assurance. Ultimately, this experience demonstrates that with proper technology and management, iron scrap can be a reliable resource for high-quality shell castings, paving the way for greener foundry practices.

From a technical perspective, the relationship between charge composition and final properties in shell castings can be modeled using regression equations. For instance, tensile strength \( \sigma_b \) might be expressed as:

$$ \sigma_b = \alpha \cdot C + \beta \cdot Si + \gamma \cdot Mn + \delta \cdot (Pearlite \%) + \epsilon $$

where \( \alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta, \epsilon \) are coefficients determined from historical data. Such models aid in predictive control for consistent shell castings. Additionally, the cooling rate \( \dot{T} \) during solidification affects microstructure; for sand-cast shell castings, \( \dot{T} \) is typically in the range of 10–30°C/s, influencing graphite formation and matrix fineness.

Overall, the integration of medium frequency melting with scrap utilization represents a best practice for foundries aiming to produce cost-effective, high-performance shell castings. By sharing these insights, I hope to contribute to the broader adoption of such methods, fostering innovation in the casting industry while emphasizing the critical role of shell castings in mechanical systems.