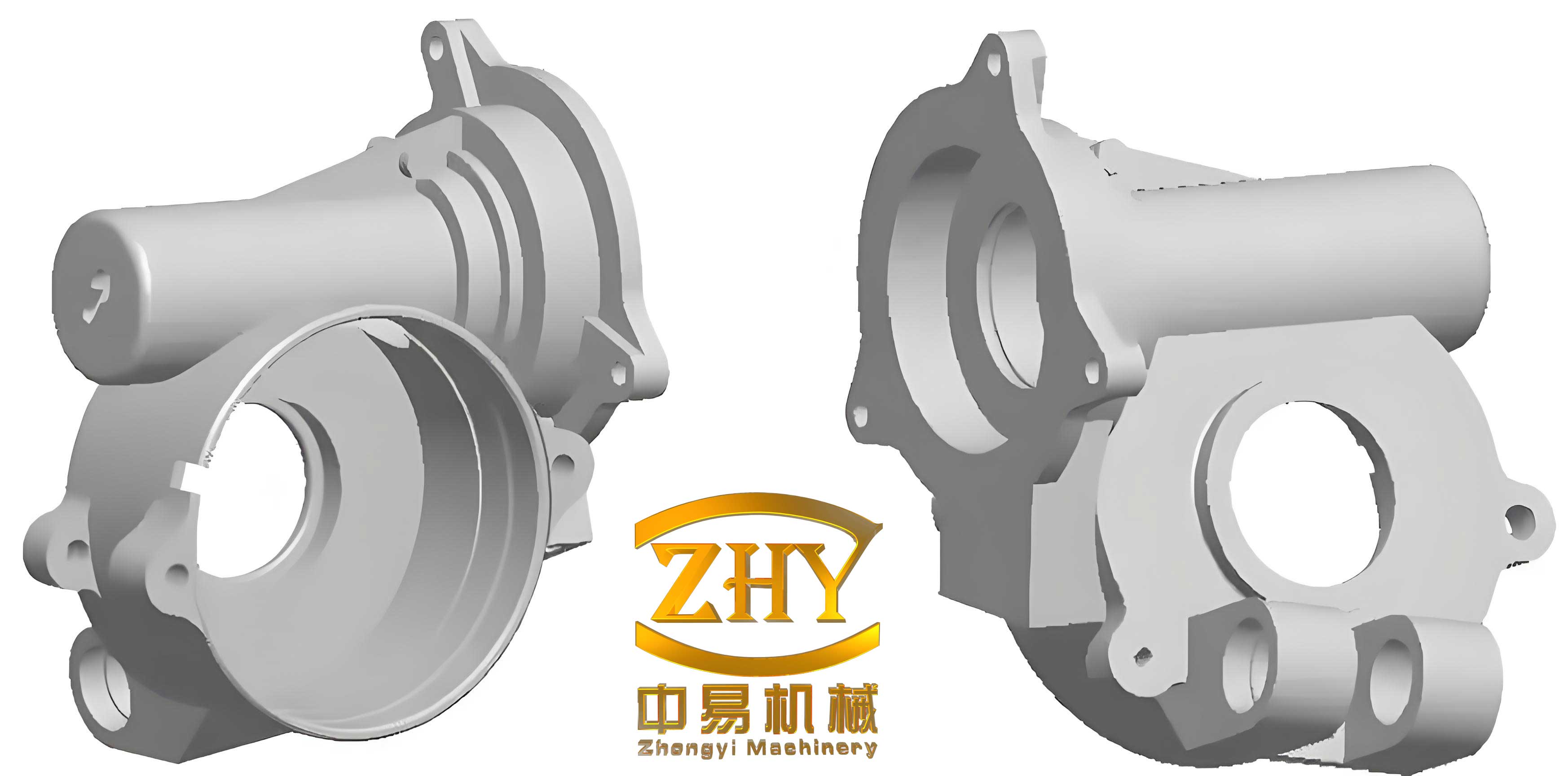

The differential housing is a critical component in automotive drivetrains, serving as the foundational structure that houses the differential gears and transmits torque to the axles. As such, the integrity and quality of this shell casting directly influence vehicle performance, durability, and safety. Traditional manufacturing approaches for differential housings often involved multi-piece assemblies or designs that introduced significant challenges during the casting process, primarily related to thermal management. This article details a comprehensive project undertaken to optimize the casting process for a specific differential housing shell, transitioning from a problematic design to a robust, high-yield production component. The core of this optimization centered on structural redesign, advanced core-making strategies, and precise process control to eliminate internal defects and enhance manufacturability.

Challenges in Traditional Shell Casting Design

The initial design of the HFF240301E-type differential housing presented classic yet severe foundry challenges. The component was originally conceived as a two-part assembly (left and right halves). This assembly required machining, bolting, and then subsequent machining of the cruciform cross-axle holes on the assembled unit. This method was not only inefficient but also prone to long-term reliability issues stemming from assembly stresses and alignment inaccuracies.

From a foundry perspective, the more immediate and critical problem was the geometry of the housing itself. The design featured numerous isolated, thick sections where metal intersections created pronounced thermal concentration zones, known as hot spots or hot junctions. In cast iron, particularly ductile iron which is common for such components, these hot spots are the primary origin of shrinkage porosity and cavity defects. The solidification sequence in such a geometry is unfavorable; the thin sections solidify and strengthen first, isolating the thicker, hotter sections. As these heavy sections finally solidify and contract, they cannot draw liquid metal from the already-solidified areas, leading to internal micro-porosity (shrinkage) or even macro-cavities (shrink holes). The susceptibility of a section to shrinkage can be estimated by its modulus, which is the ratio of volume to cooling surface area.

$$ M = \frac{V}{A} $$

Where \( M \) is the modulus (in cm or in), \( V \) is the volume of the section, and \( A \) is its surface area through which heat is dissipated. Sections with a higher modulus solidify more slowly and are prone to shrinkage. The original design’s cross-axle boss areas had a significantly higher modulus compared to the surrounding walls, creating ideal conditions for defect formation.

Key Problems Summary:

- Thermal Hot Spots: Multiple junctions created isolated, high-modulus regions.

- Shrinkage Defects: Inevitable micro-porosity and potential macro-shrinkage in the cross-axle boss areas.

- Manufacturing Complexity: Multi-stage machining and assembly increased cost and potential failure points.

- Use of Chills: To counteract hot spots, external chills were often necessary, which could lead to surface hardness variations and adverse effects on subsequent machining of critical bearing surfaces.

Structural Optimization: A Foundry-Centric Redesign

The primary objective was to redesign the geometry of the differential housing shell casting to inherently promote directional solidification and eliminate isolated thermal masses. The fundamental change was to integrate the cross-axle holes into the casting itself, moving away from the post-assembly machining approach. However, simply casting these holes creates four massive, isolated bosses—a recipe for severe shrinkage.

The breakthrough came from re-imagining the internal geometry. Instead of solid bosses, the design incorporated a sophisticated network of internal ribs and hollow structures connecting the cross-axle bearing areas to the main body of the housing and to each other. This design serves two crucial purposes:

- Modulus Reduction: It dramatically increases the cooling surface area (\(A\)) of the critical sections, thereby lowering their modulus (\(M\)).

- Feeding Path Creation: It establishes continuous thermal and liquid metal pathways between the heavier sections and the main casting body, which can act as a feeder (riser) during the final stages of solidification.

The optimized geometry ensures that the entire shell casting solidifies progressively from the thin, peripheral areas towards the thicker sections and finally to the strategically designed feeding channels. This principle is governed by Chvorinov’s rule, where solidification time \( t \) is proportional to the square of the modulus.

$$ t = k \cdot M^{n} $$

where \( k \) is a mold constant and \( n \) is typically around 2. By reducing \( M \) in potential hot spots and ensuring they are connected to larger thermal masses, we orchestrate a solidification sequence that prevents pore formation.

| Feature | Original Design | Optimized Design |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Axle Holes | Machined after assembly | Casted-in-place |

| Internal Geometry | Solid, isolated bosses | Ribbed, interconnected hollow structure |

| 4 major isolated hot spots | Distributed thermal mass, no major isolated hot spots | |

| Solidification Sequence | Random, prone to isolation | Controlled directional solidification |

| Required Chills | Extensive use necessary | Eliminated |

| Weight | Higher (solid mass) | Reduced (lightweight design) |

Casting Process Design and Engineering

A successful structural redesign must be paired with a robust and repeatable manufacturing process. The chosen production method was high-pressure green sand molding combined with an advanced core assembly system.

1. Molding Process: YJZ107 Squeeze Molding

We selected a high-pressure squeeze molding line to produce the mold halves. This process delivers exceptional mold hardness (consistently above 95 on the B-scale), which is vital for producing high-integrity shell castings.

Advantages for this Application:

- Dimensional Stability: The rigid mold wall minimizes mold wall movement during the critical graphite expansion phase of ductile iron solidification, counteracting the natural tendency for micro-expansion shrinkage.

- Precision: Excellent reproducibility of casting dimensions, ensuring consistent machining allowances.

- Surface Finish: Produces a smooth casting surface, reducing cleaning and finishing time for the final shell castings.

Pattern plates for both the cope and drag were meticulously designed and manufactured, ensuring proper draft, feeding system integration, and core print locations for the complex internal sand core.

2. Core Making & Assembly: The Monolithic Sand Core Strategy

The heart of the manufacturability for the new design was the strategy for forming the intricate internal cavity. A conventional single-piece core box was impractical. Instead, we adopted a modular, bonded assembly approach using shell-coated sand (thermoset resin-coated sand) in heated core boxes.

The core assembly was decomposed into logical sub-components:

- Main Base Core: Forms the lower internal cavity and primary mounting features.

- Main Middle Core: Forms the central cavity and connects to the base core.

- Four Cross-Axle Cores: Form the precise bearing pockets for the differential spider gears.

The assembly sequence was critical. Two primary methods were evaluated:

Method A (Offline Assembly): Bonding all six core pieces together into a single, monolithic core assembly before delivering it to the molding line. This “monolithic sand core” is then placed into the drag mold in one action.

Method B (In-Mold Assembly): First, bonding the Main Base and Main Middle cores offline. This sub-assembly is placed in the drag. Then, the four Cross-Axle cores are inserted individually into their respective prints in the drag mold, engaging with locators on the main core sub-assembly.

Process trials determined that Method B was superior for high-volume production. While Method A offered faster single-station placement, it created handling and storage challenges for the fragile, complex assembly and increased the risk of core breakage during placement. Method B, though involving multiple placement steps, was more robust, reduced handling damage, and offered greater flexibility on the production line. The bonding and sealing of core joints were achieved using a high-temperature, low-fume core adhesive, with careful attention to seam finishing to prevent metal penetration in the final shell castings.

The modulus of the sand core itself must also withstand the metallostatic pressure. The core’s cold crushing strength (CCS) is a critical parameter, defined by the resin system and curing process.

| Parameter | Method A (Offline Monolithic) | Method B (In-Mold Assembly) |

|---|---|---|

| Handling Complexity | High (large, fragile assembly) | Lower (smaller sub-assemblies) |

| Core Damage Risk | Higher | Lower |

| Line-Side Logistics | Cumbersome storage/transfer | Simpler |

| Placement Speed | Fast (one placement) | Moderate (multiple placements) |

| Process Flexibility | Low | High |

| Selected Method | No | Yes |

3. Gating and Feeding System Design

To complement the directional solidification enabled by the new geometry, a pressurized, step-gated system with a controlled choke was designed. The gating ratio (sprue:runner:gate area) was calculated to achieve rapid, turbulent-free filling while establishing a thermal gradient. The feeder (riser) was strategically placed over the heaviest section of the main housing body, which, due to the new internal rib design, now acted as the final region to solidify and could effectively feed the interconnected cross-axle regions through the internal channels. The efficiency of a riser can be described by its feeding modulus, which must be greater than the modulus of the section it is intended to feed.

$$ M_{riser} > M_{casting\_section} $$

The solidification contraction volume \( V_{shrinkage} \) that must be supplied by the riser is a function of the alloy’s shrinkage rate \( \varepsilon \).

$$ V_{shrinkage} = \varepsilon \cdot V_{casting\_fed} $$

For ductile iron, \( \varepsilon \) is typically in the range of 2-5% depending on composition and cooling rate. The riser volume must be sufficient to provide this liquid metal after accounting for its own solidification shrinkage.

Material and Metallurgical Process Control

Producing sound shell castings requires precise control over the metallurgy of ductile iron. The target material was a high-strength, ferritic-pearlitic ductile iron (e.g., GJS-500-7 or similar).

Charge Material and Chemistry

A stringent charge makeup was enforced to ensure low levels of trace elements that can interfere with graphite nodulization or promote carbides.

- High Purity Pig Iron: Low in trace elements like Ti, Pb, Sb, Bi.

- Low Manganese Steel Scrap: Mn levels were kept below 0.3% to stabilize ferrite and reduce segregation.

- Phosphorus and Sulfur Control: P was kept below 0.04% to minimize phosphide eutectic, and S was minimized (<0.015%) prior to treatment to improve Mg-treatment efficiency.

- Copper Addition: Cu was added as an alloying element (0.3-0.6%) to strengthen the matrix, increase hardness, and improve uniformity of properties throughout the section thickness of the shell castings without significantly reducing ductility.

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Mg | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Range | 3.6-3.8 | 2.3-2.6 | 0.3-0.6 |

Melting, Treatment, and Pouring

The process utilized a medium-frequency induction furnace for melting, ensuring excellent homogeneity and temperature control.

- Spheroidization: A precise amount of FeSiMg cored-wire was injected into the base iron in a tundish cover ladle. The treatment time was controlled to be under 60 seconds to minimize Mg fading and temperature loss. The reaction is simplified as:

$$ [S]_{in\,Fe} + Mg \rightarrow MgS_{(slag)} $$

$$ [O]_{in\,Fe} + Mg \rightarrow MgO_{(slag)} $$ - Inoculation: A multi-stage inoculation strategy was employed to ensure a high nodule count and prevent chilling:

- Ladle Inoculation: Primary inoculation during transfer from treatment ladle.

- Floating Inoculation: Addition of inoculant blocks to the stream during transfer.

- In-stream Inoculation: Final, precise inoculation as the iron is poured into the mold.

This practice refines the graphite structure, which is crucial for the mechanical properties and pressure tightness of the shell castings.

- Pouring Practice: The molds were poured quickly and consistently, with a target pour time of under 8 minutes for the ladle to prevent excessive temperature drop and inoculation fade.

Production Validation and Results

A controlled production trial was executed, implementing all the described optimizations: the new structural design for the housing shell, the YJZ107 molding process, the in-mold core assembly strategy (Method B), and the strict metallurgical controls.

The results were immediately evident upon shakeout and initial inspection. The shell castings exhibited clean surfaces with well-defined features. Non-destructive testing (radiographic inspection and ultrasonic testing) of sample castings from the initial batches confirmed the absence of shrinkage cavities or significant porosity in the critical cross-axle bearing areas and throughout the main body.

Key outcomes from the production validation include:

- Elimination of Hot Spots & Shrinkage: The redesigned internal geometry successfully prevented the formation of isolated thermal masses. Radiography confirmed sound metal in all previous problem areas, validating the modulus equalization and directional solidification approach.

- Elimination of Chills: The need for external chills was completely removed. This resolved the secondary issue of surface hardness variation on machined bearing surfaces, leading to more consistent and predictable machining performance and final part quality.

- Enhanced Machinability and Yield: The casting-integrated cross-axle holes only required semi-finishing (boring) rather than deep drilling from solid, significantly reducing machining time, tool wear, and cost. The overall product yield from molding to final machined part increased dramatically due to the near-total elimination of casting scrap.

- Weight Reduction: The optimized, ribbed internal structure resulted in a lighter component compared to the old design with solid bosses, contributing to vehicle lightweighting goals.

The mechanical properties of the produced shell castings were tested and met or exceeded specifications. The microstructure showed a uniform distribution of well-formed, spherical graphite nodules (ASTM Type I, II) in a matrix of ferrite and pearlite, with a nodule count exceeding 120 nodules/mm², indicative of effective inoculation.

| Metric | Status Before Optimization | Status After Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Shrinkage Defect Rate | High (in cross-axle bosses) | Negligible |

| Casting Yield | Low | High (>95% sound castings) |

| Machining Steps for Cross-Holes | Drilling & Boring (post-assembly) | Boring only |

| Use of Chills | Required | Eliminated |

| Surface Hardness Variation | Significant (due to chills) | Minimal |

| Component Weight | Higher | Reduced by ~5-8% |

Conclusion

The successful optimization of the HFF240301E differential housing shell casting process demonstrates the profound impact of an integrated, holistic engineering approach. By prioritizing foundry principles during the structural design phase—specifically through modulus control and the creation of directional solidification pathways—the root cause of shrinkage defects was systematically eliminated. This design-for-manufacturability step was the cornerstone of success.

The manufacturing process was then tailored to support this optimized design. The combination of high-pressure green sand molding for dimensional stability and a modular, bonded shell sand core system provided the necessary precision and robustness for high-volume production of these complex shell castings. Rigorous control over metallurgy, particularly low-manganese chemistry, effective Mg-treatment, and multi-stage inoculation, ensured the consistent production of high-integrity ductile iron with the required mechanical properties.

The final outcome is a superior differential housing shell casting: lighter, stronger, free from internal defects, and more efficient to manufacture. This case underscores that overcoming chronic casting defects often requires moving beyond simple process parameter adjustments and instead fundamentally re-engineering the component and its production system from the ground up. The principles applied here—thermal center management through geometry, advanced core-making, and precise metallurgical control—are universally applicable to the production of high-quality, safety-critical shell castings across the automotive and heavy machinery industries.