In the realm of advanced manufacturing, particularly for aerospace and high-performance engineering applications, the demand for complex, lightweight, and high-integrity components is ever-increasing. Titanium alloys, renowned for their excellent strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and good mechanical properties at elevated temperatures, are prime candidates for such applications. Among various fabrication techniques, investment casting, especially the shell casting process, stands out for producing net-shape or near-net-shape components with intricate geometries and superior surface finish. This method is particularly crucial for manufacturing shell castings with thin walls and complex internal features that are otherwise difficult or expensive to machine from bulk material.

However, the very attributes that make titanium desirable—its high melting point, reactivity in the molten state, and specific solidification characteristics—also render its casting process challenging. Defects such as shrinkage porosity, hot tears, and misruns are common in titanium shell castings, leading to low qualification rates, prolonged trial-and-error development cycles, and significant material waste. Traditional methods of process optimization rely heavily on empirical knowledge and physical prototyping, which are time-consuming and costly.

This work addresses these challenges by leveraging the power of numerical simulation as a virtual foundry tool. We focus on the development and optimization of the investment casting process for a specific ZTC4 titanium alloy shaped thin-walled component. The primary objective is to utilize finite element analysis (FEA) to predict and eliminate internal defects, thereby establishing a robust, first-time-right manufacturing process for high-quality titanium alloy shell castings.

1. Component Analysis and Initial Casting Layout

The subject of this study is a structural housing or casing component made from ZTC4, a widely used medium-strength (α+β) titanium alloy. Its nominal chemical composition is provided in Table 1.

| Al | V | Fe | Si | C | N | H | O | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5-6.8 | 3.5-4.5 | ≤0.40 | ≤0.15 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.25 | Bal. |

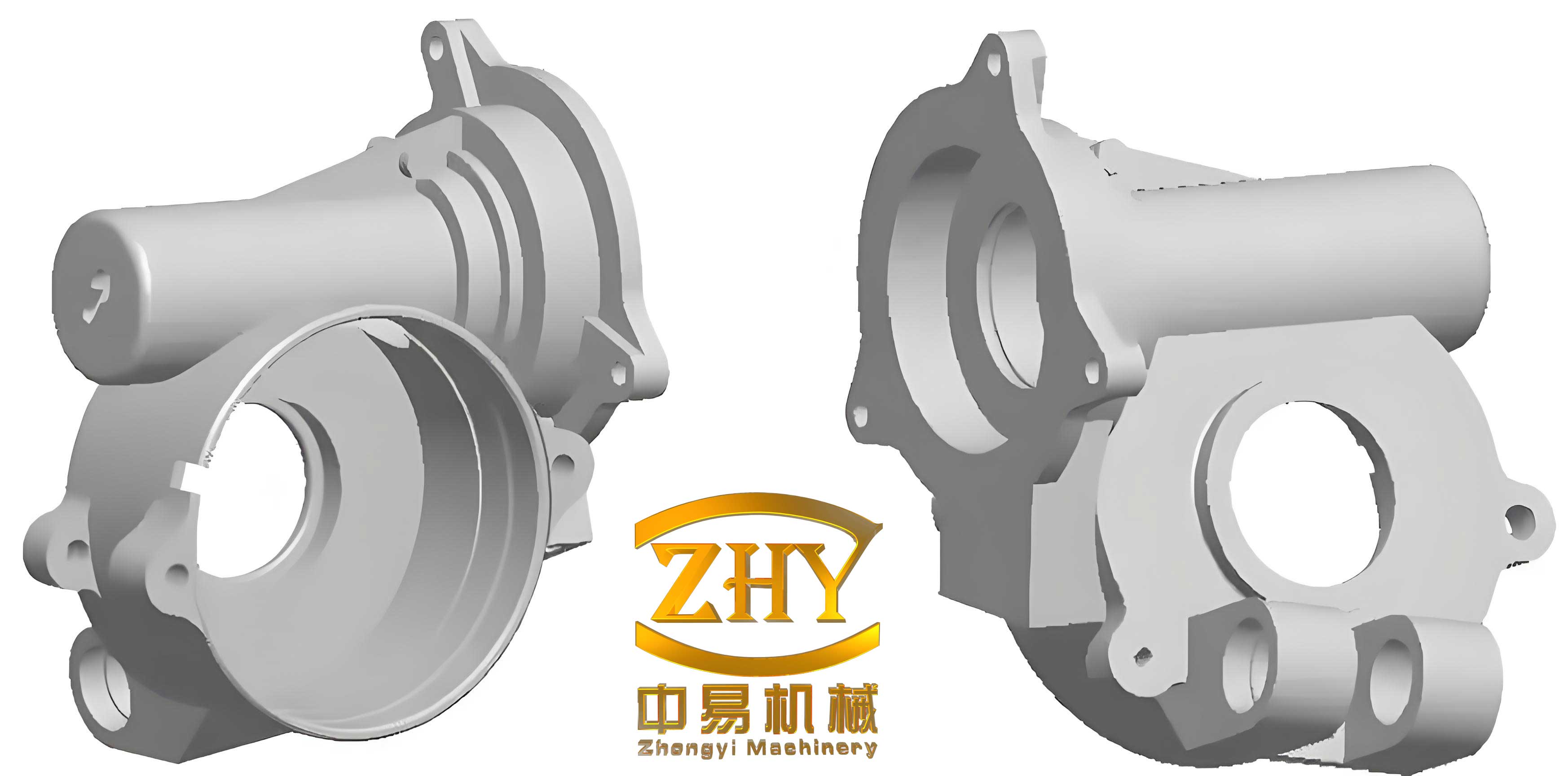

The geometry of the part is complex, characterized by an amalgamation of thin walls, varying sections, and integral features. It can be dissected into three main functional zones:

- A Circular Base/Ring: This forms the foundation of the part. Its outer wall features deep recesses, while the inner wall has a tapered protrusion, creating significant sectional variations. The largest inner diameter is approximately 60 mm. This area is prone to turbulence and premature solidification if the gating system is not properly designed.

- A Central Load-Bearing Plate (Web): This is a relatively uniform section with a nominal thickness of 7 mm. The primary metallurgical challenge here is to control the solidification sequence to prevent the formation of isolated liquid pools, which inevitably lead to shrinkage cavities.

- Wing-like Thin-Walled Structures: These are the most delicate features, with thicknesses ranging from 1.5 mm to 10.0 mm. They consist of two similar layers, each containing irregular grooves and through-holes, connected by several reinforcing ribs. Ensuring complete fill of these thin sections without cold shuts is critical.

The overall envelope dimensions are roughly 150 mm x 80 mm x 120 mm. Based on initial foundry experience, a preliminary casting layout was designed. A cluster of four parts was arranged around a central downgate to improve metal yield. The initial gating/feeding system, attached via wax assembly, included:

- Primary feeders (risers) at the bottom of the base and at the top and bottom of the wing structures. These were designed as truncated pyramids with specific dimensions.

- Four spherical side feeders (with a diameter of φ20 mm) attached to the sides of the wing structures to aid feeding.

This configuration aimed to ensure complete mold filling and provide directional solidification towards the feeders.

2. Theoretical Foundations of Numerical Simulation for Shell Castings

Numerical simulation of casting processes involves solving the coupled equations governing fluid flow, heat transfer, and solidification within the complex geometry of the mold (ceramic shell) and the casting itself. For titanium shell castings produced via vacuum investment casting, several key physical phenomena and their mathematical descriptions form the core of the model.

2.1 Governing Equations for Filling and Fluid Flow

The filling stage is modeled as a transient, incompressible, viscous flow with a moving free surface (the melt front). The molten titanium alloy is treated as a Newtonian fluid. The governing equations are the Navier-Stokes equations, comprising the continuity equation (mass conservation) and the momentum equations.

Continuity Equation:

$$ \nabla \cdot \vec{v} = 0 $$

where $\vec{v}$ is the velocity vector of the fluid.

Momentum Equation (Navier-Stokes):

$$ \rho \left( \frac{\partial \vec{v}}{\partial t} + (\vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \vec{v} \right) = -\nabla p + \mu \nabla^2 \vec{v} + \rho \vec{g} + \vec{S} $$

where:

- $\rho$ is the density of the molten metal.

- $t$ is time.

- $p$ is pressure.

- $\mu$ is the dynamic viscosity.

- $\vec{g}$ is the gravitational acceleration vector.

- $\vec{S}$ represents source terms, which can include contributions from buoyancy (Boussinesq approximation) due to temperature gradients.

A Volume-of-Fluid (VOF) or similar method is typically employed to track the evolution of the metal-air interface during mold filling.

2.2 Heat Transfer and Solidification Model

Once the mold is filled, the dominant process is heat extraction through the ceramic shell, leading to solidification. For shell castings, heat transfer is primarily conductive. Radiation and convection play secondary roles, especially in a vacuum environment, and are often simplified or incorporated into effective boundary conditions. The governing equation is the transient heat conduction equation including the latent heat release during phase change:

$$ \rho c_{eff} \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) $$

where:

- $T$ is temperature.

- $k$ is thermal conductivity.

- $c_{eff}$ is the effective specific heat, which accounts for both sensible heat and latent heat $L$ released during solidification. It is often modeled as:

$$ c_{eff} = c_p + L \frac{\partial f_s}{\partial T} $$

where $c_p$ is the specific heat at constant pressure and $f_s$ is the solid fraction, a function of temperature defined by the alloy’s solidification path (e.g., from a lever rule or Scheil model based on the phase diagram).

The boundary condition at the metal-shell interface is critical:

$$ -k_{metal} \frac{\partial T}{\partial n} \bigg|_{interface} = -k_{shell} \frac{\partial T}{\partial n} \bigg|_{interface} = h_{interface} (T_{metal} – T_{shell}) $$

where $h_{interface}$ is the interfacial heat transfer coefficient (IHTC), a crucial parameter that depends on shell material, roughness, and possible air gap formation during solidification.

2.3 Prediction of Shrinkage Defects in Shell Castings

The volumetric contraction of the metal as it transitions from liquid to solid state, combined with insufficient feeding, leads to shrinkage porosity and cavities. Numerical prediction of these defects in shell castings often relies on criteria-based methods or more advanced porous media models.

One classic criterion is the Niyama Criterion ($G/\sqrt{\dot{T}}$), where $G$ is the temperature gradient and $\dot{T}$ is the cooling rate at the end of solidification. Regions with values below a critical threshold are prone to microporosity.

For macro-porosity and pipe shrinkage, feeding flow models are used. A common approach integrates Darcy’s law for flow in a mushy zone:

$$ \vec{v} = -\frac{K}{\mu g_l} (\nabla p – \rho_l \vec{g}) $$

where:

- $K$ is the permeability of the mushy zone (dependent on solid fraction, e.g., Kozeny-Carman model).

- $g_l$ is the liquid fraction ($g_l = 1 – f_s$).

- $\rho_l$ is the density of the liquid.

- $p$ is the pressure in the liquid.

A mass conservation equation is solved simultaneously. Regions where the pressure falls below a critical value (often related to the local atmospheric or gas pressure) are predicted to contain shrinkage porosity. This is sometimes referred to as a Porous Model or POROS criterion in commercial software, which can output a scalar field representing the percentage of porosity.

The key material properties and process parameters required for an accurate simulation are summarized in Table 2.

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Typical Value/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Material Properties (ZTC4) | Density, $\rho(T)$ | Function of temperature (Solid & Liquid) |

| Specific Heat, $c_p(T)$ | Function of temperature | |

| Thermal Conductivity, $k(T)$ | Function of temperature | |

| Viscosity, $\mu$ | ~0.005-0.006 Pa·s (liquid) | |

| Latent Heat, $L$ | ~290-320 kJ/kg | |

| Solidification Range (Liquidus/Solidus) | ~1650°C / ~1600°C (approx.) | |

| Process Conditions | Pouring Temperature | 1700-1750 °C |

| Shell Preheat Temperature | 900-1000 °C | |

| Interfacial Heat Transfer Coefficient, $h_{interface}$ | 500 – 2000 W/m²·K (calibrated) | |

| Shell Properties | Material | Fused Silica, Alumina, or Mullite-based |

| Thickness | 8-12 mm (typical) |

3. Initial Process Simulation and Defect Analysis

Using the commercial FEA software ProCAST, the initial casting layout was simulated. The model incorporated the 3D geometry of the cluster, the thermophysical properties of ZTC4 and the mullite-based ceramic shell, and the process parameters listed in Table 3.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Alloy | ZTC4 |

| Shell Material | Mullite |

| Shell Thickness | 10 mm |

| Interface Heat Transfer Coefficient | 500 W/m²·K |

| Pouring Time | 5 s |

| Pouring Temperature | 1700 °C |

| Shell Preheat Temperature | 1000 °C |

| Cooling Condition | Vacuum (Radiation to ambient) |

The filling simulation showed a generally sequential fill without major issues like severe splashing or air entrapment. The metal first filled the bottom feeders and the base, then rose through the wing structures. The simulation confirmed that the thin sections were filled adequately within the total pouring time.

The critical analysis lay in the solidification simulation. The temperature field and solid fraction evolution were analyzed to identify the last regions to solidify. The results revealed a problematic pattern. While the attached feeders solidified last as intended, certain regions within the casting itself also remained liquid until very late in the process, creating isolated “hot spots.” These were primarily located in the central load-bearing plate, especially at its junctions with the circular base and the wing structures.

The porosity prediction module (using a feeding flow/POROS model) quantified this risk. Figure X (conceptual) shows the predicted shrinkage defect distribution. Significant macro-shrinkage propensity (highlighted in red) was predicted in the web region and at the web-base junction. This aligns perfectly with the thermal analysis: these areas, due to their geometry and connection to thicker sections, created thermal centers that were not effectively fed by the existing gating system. The spherical side feeders on the wings were insufficient to draw feeding metal through the long and thin paths to the central web. This simulation predicted a high probability of scrapping the part due to internal shrinkage cavities in critical structural areas.

The underlying reason can be expressed by considering the local feeding demand. The solidification shrinkage volume $V_{shrink}$ in a region is:

$$ V_{shrink} = \beta \cdot V_{region} $$

where $\beta$ is the volumetric shrinkage coefficient of the alloy (a combination of liquid contraction and solidification contraction). For the web region to be sound, the feeding metal supplied through the mushy zone must satisfy:

$$ \int_{t_{coherence}}^{t_{solid}} \vec{v}_{feed} \cdot \vec{A} \, dt \ge V_{shrink} $$

where $\vec{v}_{feed}$ is the feeding velocity governed by Darcy’s law, $\vec{A}$ is the cross-sectional area of the feeding path, $t_{coherence}$ is the time when a coherent solid network forms, and $t_{solid}$ is the local solidus time. In the initial design, the permeability $K$ of the long, thin paths from the feeders to the web decreased rapidly, and the pressure drop $\nabla p$ was too high, causing $\vec{v}_{feed}$ to become negligible before the web solidified, leading to $V_{shrink}$ not being compensated.

4. Iterative Process Optimization via Simulation

Based on the diagnosis from the initial simulation, an optimized gating and feeding system was designed iteratively using the simulation software. The primary objective was to transform the thermal center in the load-bearing web into a directionally solidifying region fed by a dedicated riser. The key modifications were:

- Addition of Dedicated Top and Bottom Feeders on the Web: New, sizable truncated pyramid feeders were attached directly to the top and bottom edges of the central load-bearing plate. Their dimensions (e.g., 50mm x 20mm base, 35mm height) were calculated to provide sufficient thermal mass and liquid metal reservoir to feed the shrinkage of the entire web section.

- Strategic Placement of a Feeder on the Base: An additional feeder was added to the top of the circular base ring to create a more favorable thermal gradient and feed the web-base junction directly.

- Adjustment of Existing Feeders: The original feeders on the wing tips and base bottom were slightly resized to maintain overall thermal balance while ensuring they served their local areas without interfering with the new feeding strategy for the web.

The new cluster layout was simulated with identical process parameters. The results demonstrated a dramatic improvement.

Filling Analysis: The filling remained smooth and complete. The new feeders filled sequentially without causing turbulence.

Solidification and Thermal Analysis: The most significant change was observed in the solidification sequence. The temperature gradient now clearly pointed from the extremities of the casting (the thin wings and base edges) towards the newly added feeders on the web and the base. The web itself was no longer a thermal center; instead, it solidified progressively towards the feeders attached to it. The last points to solidify were now safely within the bodies of the main feeders, as desired for sound shell castings.

The evolution of the solid fraction $f_s$ can be described to highlight the improved directionality. Let $x$ be a coordinate from the tip of a wing towards the web feeder. The improved process ensures:

$$ \frac{\partial f_s(x,t)}{\partial t} > 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{\partial T(x,t)}{\partial x} < 0 $$

for a longer duration during solidification, indicating directional heat flow towards the feeder.

Defect Prediction: The porosity simulation for the optimized layout showed a complete elimination of the predicted shrinkage in the load-bearing web and its junctions. All predicted porosity was successfully moved into the feeder heads, which are subsequently removed during machining. The final predicted defect map for the casting proper was clean, indicating a high likelihood of producing a sound part.

A comparative summary of key simulation metrics between the initial and optimized designs is presented in Table 4.

| Metric | Initial Design | Optimized Design |

|---|---|---|

| Last-to-Solidify Region | Central Web & Web-Base Junction | Feeder Heads (Top/Bottom Web Feeders, Base Feeder) |

| Predicted Shrinkage in Critical Web | High Probability (Macro-porosity) | None |

| Solidification Directionality | Poor (Multiple isolated thermal centers) | Excellent (Directional towards major feeders) |

| Feeding Path Efficiency | Low (Long, restrictive paths to web) | High (Direct, short paths from dedicated feeders) |

| Estimated Sound Yield | Low (<50% projected) | High (>95% projected) |

5. Experimental Validation and Production Results

To validate the numerical predictions, the optimized process was translated into physical production. Wax patterns were manufactured and assembled into trees replicating the simulated cluster. A multilayer ceramic shell was built using a standard investment process with mullite-based slurries and stuccos. The shells were dewaxed, fired, and then cast in a vacuum arc skull melting and casting furnace using ZTC4 alloy.

The casting parameters closely followed those used in the simulation: a pouring temperature of ~1700°C into preheated shells at ~1000°C. After casting, the shells were removed, and the clusters were cut apart. The feeders were removed via abrasive cutting, leaving the final cast components.

The castings underwent thorough non-destructive evaluation (NDE) using radiographic inspection (X-ray). The results were in excellent agreement with the simulation. Radiographs of the critical web and junction areas showed no indications of shrinkage porosity or cavities. The internal soundness of the shell castings met the stringent acceptance criteria defined by relevant aerospace standards (e.g., equivalent to ASTM E192).

Subsequent to the successful prototype trials, the optimized process was scaled for a production batch of over 40 clusters. The consistency of the results was remarkable, with a qualification rate exceeding 95%, confirming the robustness and reliability of the simulation-optimized process. This high yield stands in stark contrast to the anticipated high scrap rate from the initial design, resulting in substantial savings in material, energy, and time.

6. Conclusion and Broader Implications

This study successfully demonstrates the integral role of numerical simulation in the development and optimization of complex titanium alloy shell castings. By applying finite element analysis based on fundamental principles of fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and solidification, a problematic initial casting design was systematically diagnosed and corrected.

The key to success was the identification of inappropriate thermal gradients and feeding paths that led to shrinkage defects in a critical structural region. Through virtual iteration, an optimized gating system was developed that established proper directional solidification, effectively moving the thermal centers into strategically placed feeder heads. The final simulation predicted, and subsequent physical production confirmed, the manufacture of sound, high-integrity shell castings.

The mathematical models employed—from the Navier-Stokes equations for filling to the heat conduction equation with latent heat and the Darcy-based feeding flow models for defect prediction—provided a comprehensive digital twin of the physical process. The close correlation between simulation results and experimental validation underscores the maturity and reliability of modern casting simulation tools for reactive alloys like titanium.

The methodology outlined here provides a general framework for tackling the challenges associated with thin-walled, complex geometry shell castings. It moves the industry away from reliance on empirical guesswork and costly physical trials towards a science-based, predictive engineering approach. This leads to:

- Reduced Development Time and Cost: Multiple design iterations can be performed virtually in days rather than the weeks or months required for physical trials.

- Improved First-Pass Yield: Significantly higher confidence in producing defect-free parts on the first production run.

- Enhanced Component Performance: By guaranteeing internal soundness in critical areas, the mechanical performance and reliability of the final components are assured.

- Material Efficiency: Optimal feeder design minimizes the amount of metal recycled, improving yield and sustainability.

Future work can integrate further sophistication into the models, such as more accurate prediction of microstructural evolution (grain size, morphology) within titanium shell castings, modeling of potential shell-metal reactions (alpha-case formation), and the simulation of residual stresses and distortion during cooling. Furthermore, coupling process simulation with structural performance simulation (e.g., fatigue life prediction) will enable true performance-based design of cast components. The continued advancement and application of these numerical tools are essential for pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the manufacturing of advanced titanium alloy shell castings for the most demanding applications.