The relentless pursuit of higher performance, efficiency, and reliability in modern aviation has placed unprecedented demands on the materials used within aeroengines. Among the most critical components are the intricate oil pump and accessory shell castings. These components are characterized by highly complex geometries, with thin walls, internal networks of蜿蜒油路, and significant variations in section thickness. Such complexity necessitates manufacturing via casting processes. However, these shell castings must also operate under severe conditions—handling high-pressure fluids at elevated temperatures while maintaining absolute structural integrity and leak-tightness. This combination of intricate manufacturability requirements and extreme service conditions creates a significant materials engineering challenge.

Traditionally, cast aluminum alloys like ZL101A (a variant of Al-Si-Mg) have been employed for such shell castings due to their excellent castability, low hot tearing tendency, and good pressure tightness. Their fluidity allows them to fill intricate sand cores and thin sections in metal molds, leading to high-quality castings with minimal defects. Yet, their Achilles’ heel is thermal stability. The primary strengthening phase in ZL101A is the metastable β” (Mg5Si6) precipitate, which coarsens rapidly at temperatures exceeding 150°C, leading to a precipitous drop in strength. As next-generation engines push operational temperatures higher, the mechanical performance of ZL101A becomes a limiting factor.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the high-strength ZL205A (Al-Cu based) alloy. It offers exceptional room-temperature tensile strength, often exceeding 450 MPa in the T6 temper, making it comparable to some forged alloys. However, its applicability for complex shell castings is severely hampered by poor casting characteristics. Its long freezing range promotes a pasty mode of solidification, leading to:

$$ f_s^{pasty} = \int_{T_l}^{T_s} g(T) dT $$

where $f_s^{pasty}$ represents the fraction of solid formed over a wide temperature range $T_l$ to $T_s$, and $g(T)$ is a distribution function. This results in:

- Low fluidity, causing misruns and cold shuts in thin sections.

- High hot tearing susceptibility, as the extensive mushy zone cannot accommodate thermal stresses during solidification shrinkage.

- Pronounced microporosity, detrimental to the pressure tightness essential for pump shell castings.

Consequently, ZL205A is often restricted to simpler, sand-cast geometries rather than complex metal-mold shell castings.

This performance gap has driven the development of a new generation of cast aluminum alloys aimed at synergizing the castability of Al-Si systems with the strength and thermal stability of Al-Cu systems, further enhanced by strategic microalloying. This article delves into one such innovative alloy—an Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Sc system—evaluating its fundamental properties and, most importantly, its successful deployment in manufacturing high-integrity aeroengine shell castings.

Alloy Design Philosophy and Chemical Composition

The novel alloy is based on an Al-7Si matrix. Silicon is pivotal for imparting excellent casting characteristics: it improves fluidity, reduces shrinkage, and lowers the thermal expansion coefficient. The core of the strengthening strategy lies in the combined addition of Copper (~4%) and Magnesium (~0.35%). This combination enables the formation of multiple strengthening phases. Upon artificial aging (T6 temper), the alloy can precipitate both θ’ (Al2Cu) and Q’ (Al5Cu2Mg8Si6) phases. While θ’ provides significant strengthening, the Q’ phase is renowned for its superior thermal stability, resisting coarsening at temperatures up to 300°C. The synergy can be conceptually represented by a combined strengthening contribution:

$$ \Delta\sigma_{ppt} = \Delta\sigma_{\theta’} + \Delta\sigma_{Q’} $$

where $\Delta\sigma_{ppt}$ is the total precipitation strengthening increment.

The critical microalloying element is Scandium (Sc), added at approximately 0.15 wt.%. Scandium plays a multifaceted role:

- Primary Grain Refinement: Forms fine, coherent Al3Sc dispersoids that act as potent nucleation sites for α-Al grains, refining the as-cast microstructure.

- Enhanced Thermal Stability: Sc has been observed to segregate at the interface between the θ’ precipitate and the Al matrix, reducing the interfacial energy. This effectively raises the activation energy for Ostwald ripening, slowing down the coarsening kinetics of θ’ at elevated temperatures. The modified coarsening rate constant can be considered as:

$$ K_{modified} = K_0 \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{Q_{interface}}{RT}\right) $$

where $K_0$ is the intrinsic coarsening rate, $Q_{interface}$ is the increased activation energy due to Sc segregation, $R$ is the gas constant, and $T$ is the absolute temperature.

The nominal and actual compositions of this novel alloy are summarized below, highlighting its key constituents.

| Element | Nominal (wt.%) | Actual (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|

| Si | 7.0 | 7.1 |

| Cu | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| Mg | 0.35 | 0.32 |

| Sc | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Al | Bal. | Bal. |

Evaluation of Foundry Characteristics: Fluidity and Hot Tearing

Before committing to production, the casting performance of the new alloy was rigorously benchmarked against ZL101A and ZL205A. The fluidity, a measure of how well molten metal fills a mold, was tested using a standard spiral mold preheated to 200°C. The results were clear:

- ZL101A: >420 mm (Excellent)

- New Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Sc Alloy: 400 mm (Very Good)

- ZL205A: 245 mm (Poor)

The new alloy’s fluidity is vastly superior to ZL205A, a direct consequence of its lower liquidus temperature and the presence of Si, which reduces the effective viscosity of the semi-solid slurry. The fluidity length ($L_f$) can be related to material and process parameters by an equation of the form:

$$ L_f \propto \frac{\Delta T_{superheat} \cdot v_{pour}}{\sqrt{\mu \cdot \kappa}} $$

where $\Delta T_{superheat}$ is the superheat, $v_{pour}$ is the pouring velocity, $\mu$ is the effective viscosity, and $\kappa$ is the thermal diffusivity of the mold. The Si content favorably affects $\mu$.

Hot tearing susceptibility was assessed using constrained ring casting tests. A lower critical ring diameter at which the first crack appears indicates better resistance. The findings were as follows:

| Alloy | First Crack Appearance (Ring Width) | Hot Tearing Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| ZL101A | No crack observed | Best |

| New Alloy | 5.0 mm | Good |

| ZL205A | 25.0 mm | Poor |

This behavior is explained by solidification modeling (Scheil-Gulliver simulation). The key parameter is the solidification range ($\Delta T_{frz} = T_{liq} – T_{sol}$) and the thermal gradient ($G$). A wider pasty zone increases strain concentration in interdendritic regions. The hot tearing susceptibility index ($HTS$) often correlates with the derivative $|dT/df_s^{1/2}|$ near the end of solidification ($f_s \rightarrow 1$). A higher value indicates greater susceptibility.

$$ HTS \propto \left| \frac{dT}{df_s^{1/2}} \right|_{f_s \to 1} $$

Calculations for the three alloys in the final stages of solidification confirm the experimental ranking: ZL205A has the highest $|dT/df_s^{1/2}|$, followed by the new alloy, and then ZL101A. This demonstrates that the new alloy offers a favorable compromise, possessing significantly better hot tearing resistance than ZL205A, which is crucial for the production of sound, crack-free shell castings.

Microstructure and Mechanical Performance

The as-cast microstructure of the novel alloy exhibits a refined dendritic α-Al matrix with eutectic silicon particles distributed along the interdendritic regions. Compared to ZL101A, additional intermetallics such as blocky Al2Cu and fine primary Al3(Sc,Zr) can be observed. Following a standard T6 heat treatment (495°C/24h solution + 180°C/8h aging), the microstructure transforms. The eutectic Si spheroidizes, and the majority of the Cu and Mg dissolves into the matrix, only to re-precipitate as a dense dispersion of nano-scale precipitates during aging.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) reveals the true strength of this alloy system: a dual-precipitate structure. Alongside the classic plate-like θ’ (Al2Cu) phases, a high number density of lath-shaped or globular Q’ (Al5Cu2Mg8Si6) phases are present. The Orowan strengthening mechanism governs the contribution from these non-shearable precipitates:

$$ \Delta\sigma_{orowan} = M \frac{0.4 G b}{\pi \sqrt{1-\nu}} \frac{\ln(2\bar{r}/b)}{\lambda} $$

where $M$ is the Taylor factor, $G$ is the shear modulus, $b$ is the Burgers vector, $\nu$ is Poisson’s ratio, $\bar{r}$ is the average precipitate radius, and $\lambda$ is the inter-precipitate spacing. The fine $\lambda$ resulting from this dual-precipitate system yields high strength.

The room and elevated temperature tensile properties are the ultimate validation. The table below compares the performance of separately cast test bars.

| Alloy (T6 Temper) | Room Temp. Rm (MPa) | Room Temp. A (%) | 250°C Rm (MPa) | 250°C A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Sc | 425 ± 7 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 242 | 2.0 |

| ZL101A | 310 ± 5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 140 | 9.0 |

| ZL205A (Reference) | 484 ± 7 | 7.2 ± 7.0 | ~204 | ~10.5 |

The data reveals the new alloy’s unique position: its room-temperature strength is significantly (over 115 MPa) higher than ZL101A, though its ductility is lower. The lower ductility is primarily attributed to the presence of micro-shrinkage porosity associated with its wider solidification range compared to ZL101A, and to the stress concentration effects of the hard, brittle precipitates and eutectic Si. Most importantly, at 250°C, its strength surpasses that of the high-strength ZL205A alloy by nearly 20%, while retaining a strength advantage of over 100 MPa against ZL101A. This superior retention of strength at temperature, governed by the thermal stability of Q’ and Sc-modified θ’, validates its designation as a heat-resistant alloy suitable for demanding shell castings.

Manufacturing Complex Aeroengine Shell Castings

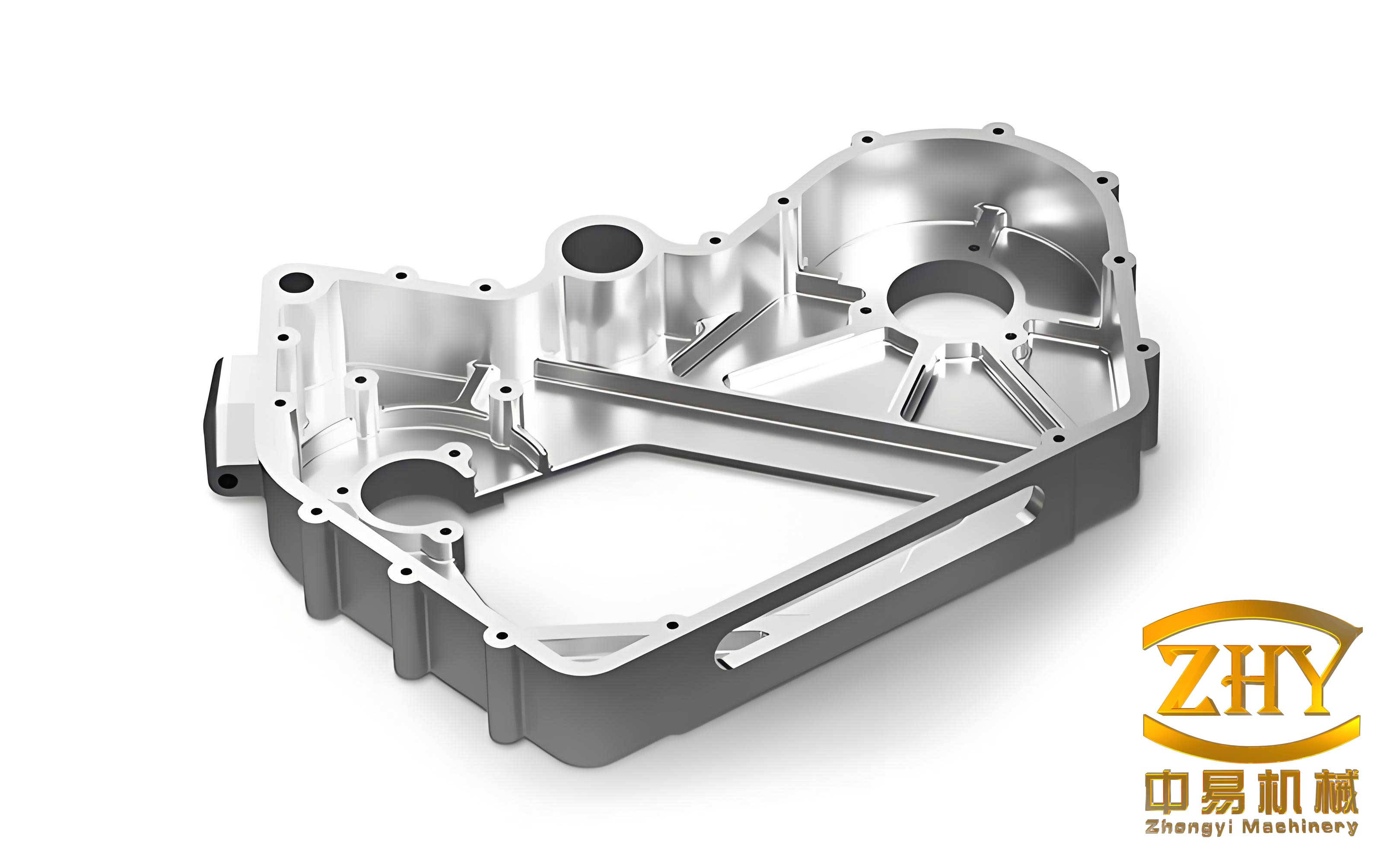

The true test of any engineering material is its performance in a real component. The target component was an oil pump housing—a quintessential complex aeroengine shell casting. Its challenges encapsulate all the difficulties in casting:

- Geometric Complexity: Overall dimensions of ~260mm x 220mm x 60mm with numerous thin (4-5mm) internal ribs and walls.

- Variable Section Thickness: Transition from 4mm thin walls to 25mm thick mounting bosses, creating isolated hot spots.

- Intricate Internal Cavities: A labyrinth of interconnected oil galleries, necessitating the use of complex, multi-part resin-bonded sand cores.

- Stringent Requirements: Pressure tightness at 0.5 MPa air pressure, structural integrity under 33 MPa hydraulic pressure, and high internal quality per aerospace standards (e.g., HB 963).

Given the alloy’s demonstrated metal-mold capability, a tilt-pour permanent mold process was selected. This process minimizes turbulence, allows for controlled filling of thin sections, and promotes directional solidification towards the risers.

The casting process was meticulously designed and simulated using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and solidification software. The governing equations for mold filling (Navier-Stokes with volume-of-fluid method) and heat transfer were solved iteratively:

$$ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = 0 $$

$$ \frac{\partial (\rho \vec{v})}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} \vec{v}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot \vec{\tau} + \rho \vec{g} + \vec{F}_{drag} $$

$$ \rho C_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} + \rho C_p \vec{v} \cdot \nabla T = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{Q}_{latent} $$

where $\vec{F}_{drag}$ accounts for the drag in the mushy zone (modeled using the Carman-Kozeny equation) and $\dot{Q}_{latent}$ is the latent heat release. The simulation guided the placement of multiple risers on the thick sections (top and side bosses) to ensure adequate feeding and shrinkage compensation. The mold was preheated to 300°C, and the alloy was poured at 740°C with a controlled tilt sequence over 11 seconds.

Quality Assessment of Produced Shell Castings

A batch of ten shell castings was produced using the optimized process. After shakeout, heat treatment (T6), and shot blasting, they underwent a comprehensive quality inspection protocol. The results were highly promising and directly comparable to established production with ZL101A.

1. Mechanical Properties (From Casting Coupons): Test bars machined from designated locations on the castings themselves showed even higher strength than separately cast bars, a phenomenon often due to slightly faster cooling in the metal mold.

$$ R_{m}^{casting-coupon} = 448 \pm 23 \text{ MPa} $$

This represents a massive 200+ MPa advantage over ZL101A shell castings from the same geometry.

2. Internal Soundness:

- Radiographic Inspection (X-Ray): No major shrinkage porosity or core-related defects were detected in the critical areas of the shell castings. The internal quality met the stringent Class II requirements of the relevant standard, with an 80% first-pass yield, equaling the benchmark set by ZL101A castings.

- Macroetch Examination: Samples from riser junctions showed a pore density rated at Level 1 (the best level), indicating very low gas porosity.

3. Surface Quality and Integrity: Liquid penetrant inspection (FPI) confirmed the absence of surface discontinuities such as hot tears, cold cracks, or cold shuts on all ten shell castings. This is a direct result of the alloy’s good hot tearing resistance and fluidity, validating the initial processability assessment.

4. Functional Performance:

- Air Pressure Test (0.5 MPa): All castings were pressurized internally with air and submerged. No leakage was observed, confirming exceptional pressure tightness.

- Hydraulic Burst Test (33 MPa): All shell castings withstood the high-pressure hydraulic test without failure or leakage, demonstrating that the achieved mechanical properties and internal soundness were fully adequate for the service load.

Conclusion and Perspective

The development and application of the novel Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Sc cast aluminum alloy successfully bridge the critical performance gap between high-castability, low-strength alloys and high-strength, poor-castability alloys. Its balanced design provides a compelling property portfolio:

| Property Category | Performance vs. ZL101A | Performance vs. ZL205A | Implication for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Castability | Slightly lower fluidity, comparable hot tear resistance. | Significantly superior in both fluidity and hot tear resistance. | Enables reliable production of complex, thin-walled geometries in metal molds. |

| Room-Temp Strength | ~35-40% higher. | ~10-15% lower. | Allows for weight reduction or higher design pressures. |

| High-Temp Strength (250°C) | ~70% higher. | ~15-20% higher. | Enables use in higher-temperature engine environments. |

| Pressure Tightness | Equivalent (Grade 1 porosity). | Typically superior due to narrower pasty zone. | Ensures leak-free operation in pump and manifold applications. |

The successful manufacture and validation of the complex oil pump housing shell castings demonstrate that this alloy is not just a laboratory curiosity but a production-ready material. It offers a clear pathway for upgrading the performance of critical aeroengine components where complexity, leak-tightness, and high-temperature strength are non-negotiable. Future work may focus on further optimizing the Mg/Cu ratio and Sc content to enhance ductility without compromising strength or thermal stability, and on developing specialized heat treatment cycles to tailor the precipitate mix for specific application temperature windows. The integration of such advanced cast aluminum alloys will be fundamental in realizing the next generation of efficient and powerful aviation propulsion systems.