In my extensive experience within the foundry industry, the design and production of high-integrity shell castings, such as differential housings, represent one of the most demanding engineering challenges. These components are critical in automotive drivetrains, requiring exceptional internal soundness and mechanical properties. The specific differential housing shell casting discussed here, with a mass of 31.6 kg and manufactured from ductile iron, features a substantial hot spot with a maximum hot spot circle diameter of 52 mm. Achieving the client’s stringent internal quality specifications—mapping to ASTM E446 Grades 2, 3, and 4 for high, general, and low density regions, respectively—necessitated a meticulously engineered casting process. The material specification, D25-2, corresponds to QT550-6 in Chinese standards, with a mixed matrix of pearlite and ferrite (pearlite ≥50%), tensile strength of 552 MPa, yield strength of 379 MPa, elongation of 6%, and a hardness range of 187-255 HB. This article details the first-person journey of developing a robust casting process for these complex shell castings, leveraging systematic design, numerical simulation, and practical validation, while consistently focusing on the principles applicable to thick-section shell castings.

The foundational step in any casting process design is a thorough structural analysis of the shell casting itself. For this differential housing, the geometry is complex, integrating flanges, bosses, and varying wall thicknesses that create natural thermal centers. The primary challenge identified was the large thermal mass at the flange-adjacent boss, acting as a major hot spot. This inherent characteristic of many shell castings promotes shrinkage porosity if not properly managed during solidification. The material’s solidification behavior, particularly the graphitic expansion of ductile iron, adds another layer of complexity. A summary of the key material requirements for this shell casting is presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | Requirement (D25-2 / QT550-6) |

|---|---|

| Matrix Structure | Pearlite + Ferrite (Pearlite ≥ 50%) |

| Tensile Strength | ≥ 552 MPa |

| Yield Strength | ≥ 379 MPa |

| Elongation | ≥ 6% |

| Hardness | 187 – 255 HB |

| Key Analog Standard | ASTM A536 (Equivalent Grade) |

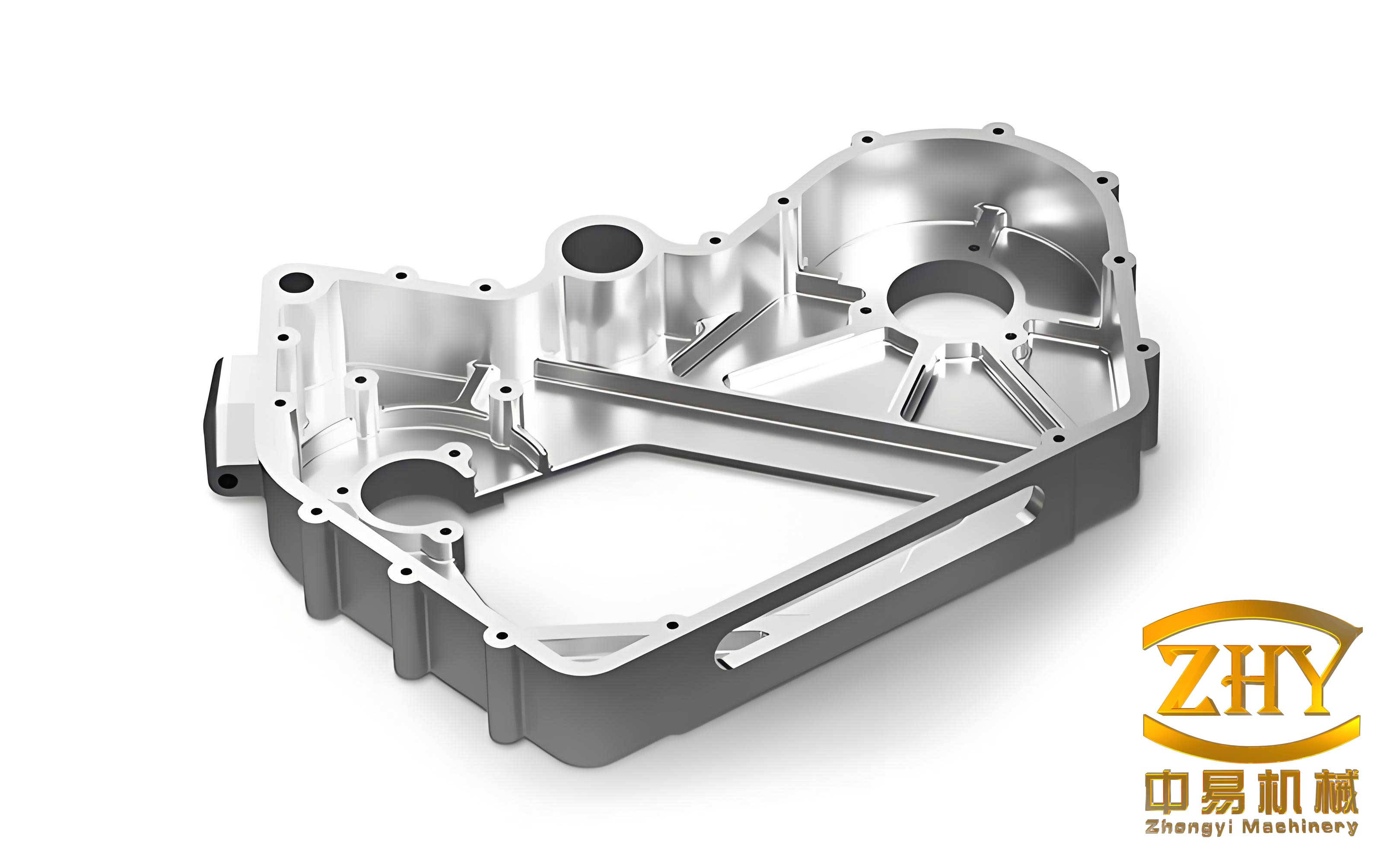

The geometry of this specific shell casting, highlighting its thick sections and potential isolated hot spots, is crucial for visualization. Below is an illustration that aids in understanding the complex three-dimensional form of such differential housing shell castings.

The casting process was developed for production on a KW high-pressure molding line with a mold plate size of 1040 mm x 840 mm. Given the shell casting’s maximum outer diameter of 350 mm, a pattern of four castings per mold was selected to optimize yield and productivity. The parting line was strategically placed at the flange, and the casting was oriented upside-down (inverted) in the mold. This orientation positions the major hot spot within the drag (lower mold half), which inherently increases the metallostatic pressure from any feeding system placed above it, enhancing feeding efficiency—a critical consideration for heavy shell castings. Furthermore, this orientation allowed for the formation of certain undercut features via the mold itself, reducing core weight and improving dimensional stability. A washout relief pocket was incorporated into the drag pattern to prevent sand inclusion defects during core setting, and feeding aids (chills or padding) were added at specific locations to ensure open feeding paths until late in solidification.

The heart of the process design lies in the gating and feeding systems. For shell castings produced in multi-cavity molds, the SPRUE-RUNNER gating system theory, as advocated by Karsay for ductile iron, is often optimal. This system places the flow control choke at the runner, allowing for a pressurized system upstream and an open system downstream. This hybrid closed-open design offers superior slag trapping capability while maintaining relatively calm mold filling. The first step was calculating the pouring time based on the total weight of metal required. The formula used is empirical:

$$ t = S_1 \sqrt{G_L} $$

Where \( t \) is the pouring time in seconds, \( G_L \) is the total weight of molten metal in kg (including castings and estimated gating/feeding system weight), and \( S_1 \) is a coefficient dependent on casting wall thickness. For this shell casting with its medium-to-thick sections, \( S_1 \) was selected as 2.2. The total casting weight for four pieces was \( 4 \times 31.6 \, \text{kg} = 126.4 \, \text{kg} \). Estimating the gating and riser system weight at 30 kg, the total metal weight \( G_L \) became 156.4 kg. Substituting into the formula:

$$ t = 2.2 \times \sqrt{156.4} \approx 27.4 \, \text{s} $$

A pouring time of approximately 27 seconds was targeted. Next, the choke cross-sectional area was determined using the hydraulic principle formula for pressurized systems:

$$ A_{\text{choke}} = \frac{G_L}{\rho_L \mu t \sqrt{2g H_p}} $$

Where:

– \( A_{\text{choke}} \) is the total choke area (cm²).

– \( \rho_L \) is the density of liquid iron (\( 7.3 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{kg/cm}^3 \)).

– \( \mu \) is the discharge coefficient (taken as 0.42 for iron castings).

– \( g \) is acceleration due to gravity (980 cm/s²).

– \( H_p \) is the effective metallostatic head height (30 cm).

Substituting the values:

$$ A_{\text{choke}} = \frac{156.4}{7.3 \times 10^{-3} \times 0.42 \times 27.4 \times \sqrt{2 \times 980 \times 30}} \approx 20.1 \, \text{cm}^2 $$

Thus, the total runner choke area \( \Sigma A_r \) was set to 20 cm². For a closed-open system, the typical cross-sectional area ratios between sprue base, runner choke, and ingate areas are \( \Sigma A_s : \Sigma A_r : \Sigma A_g = 1.3 : 1.0 : 1.2 \). This yielded:

$$ \Sigma A_s = 1.3 \times 20 = 26 \, \text{cm}^2 $$

$$ \Sigma A_g = 1.2 \times 20 = 24 \, \text{cm}^2 $$

The gating system was implemented with two ceramic filters placed on either side of the sprue in the runner. To promote temperature uniformity and a more simultaneous solidification pattern in the main body of the shell castings—thereby isolating the major hot spot for directed feeding—eight flat, thin ingates were used. These flat ingates help minimize slag entrainment and distribute heat evenly. The three-dimensional layout of this gating system was designed accordingly.

Feeding such a shell casting, with its pronounced hot spot, required more than conventional blind risers. The strategy was to encourage overall simultaneous solidification where possible and then apply highly efficient feeding to the isolated thermal center. Exothermic-insulating riser sleeves were chosen for this task. Their dual action of generating heat via chemical reaction and retaining heat via insulation significantly extends the liquid life of the riser, boosting its feeding efficiency (\( \eta \)) to around 35% or higher, compared to perhaps 10-15% for a conventional sand riser. The required feeding metal volume was calculated first. The volumetric shrinkage (\( \varepsilon \)) for ductile iron is approximately 4%. For one shell casting:

$$ \text{Required Feed Metal Mass} = \text{Casting Mass} \times \varepsilon = 31.6 \, \text{kg} \times 0.04 = 1.264 \, \text{kg} $$

Given the riser efficiency \( \eta = 0.35 \), the necessary riser metal mass is:

$$ M_{\text{riser}} = \frac{1.264}{0.35} \approx 3.61 \, \text{kg} $$

An exothermic sleeve size of 80/110 (top diameter 110 mm, bottom diameter 80 mm) was selected, which holds approximately 3.8 kg of liquid iron, satisfying the requirement. The design of the riser neck is paramount in ductile iron shell castings due to the pronounced graphite expansion phase. The neck must be open during the liquid contraction phase to allow feeding and then constrict or “close” at the onset of expansion to prevent metal reflux from the casting back into the riser. This is governed by the modulus (cooling rate), defined as Volume/Surface Area. The modulus of the chosen riser (\( M_R \)) was calculated from its geometry to be approximately 1.4 cm. The riser neck modulus (\( M_N \)) is typically designed as:

$$ M_N = k \cdot M_R $$

Where \( k \) is a factor, often between 0.5 and 0.67 for effective neck control in ductile iron. Using \( k = 0.67 \):

$$ M_N = 0.67 \times 1.4 = 0.938 \, \text{cm} $$

A cylindrical neck with a modulus matching this value was designed. To facilitate easy separation of the riser from the finished shell casting, a break-core (washburn core) was placed between the riser and the casting body. Furthermore, a “riser pad” or extension was provided below the riser to ensure an adequate reservoir of hot metal directly above the hot spot. Table 2 summarizes the key feeding system parameters for this shell casting.

| Design Element | Calculation/Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Riser Type | Exothermic-Insulating Sleeve (80/110) | Prolonged feeding for hot spot |

| Riser Metal Mass | ~3.8 kg | Exceeds required feed metal (1.26 kg) |

| Estimated Efficiency (η) | 35% | High yield feeding |

| Riser Neck Modulus (MN) | 0.94 cm (from MN=0.67MR) | Control feeding & expansion phases |

| Neck Shape | Cylindrical | Controlled solidification |

| Auxiliary Feature | Break-Core / Washburn Core | Easy riser removal post-casting |

Before committing to expensive tooling and trial runs, numerical simulation of the solidification process is an indispensable tool for optimizing shell casting processes. Using dedicated casting simulation software (such as InteCast/CAE), a full 3D model encompassing the shell castings, cores, gating, and feeding systems was created and meshed. A pure solidification simulation was run, ignoring fluid flow, to analyze the thermal gradients and predict shrinkage porosity. The results were visualized through temperature contour plots and shrinkage prediction modules at various solidification times. The simulation clearly showed the large hot spot at the flange boss solidifying last. Crucially, it demonstrated that the exothermic riser remained liquid significantly longer than this hot spot, with an open feeding channel via the designed neck until the late stages of solidification. The final predicted shrinkage map indicated that all porosity was successfully contained within the riser itself, with the shell casting body predicted to be sound—achieving the desired Grade 2 internal density. This virtual prototyping phase confirmed the efficacy of the gating and riser design for these specific shell castings, allowing for confidence before physical trials.

The ultimate test of any casting process design is physical production. The tooling was manufactured based on the finalized digital design. For the first trial pours, additional metallurgical and process safeguards were implemented to further secure the quality of the shell castings. Firstly, the carbon equivalent was slightly increased within specification limits, and an effective inoculation practice was used to maximize the number of graphite nodules. This enhances the graphitic expansion during eutectic solidification, boosting the natural “self-feeding” capability of the ductile iron shell castings. Secondly, the mold hardness was maximized using the high-pressure molding line to create a rigid mold wall. This rigidity is essential to withstand the internal expansion pressure without mold wall movement, which would otherwise create additional volume deficits needing feeding. Thirdly, the pouring temperature was carefully controlled to an optimum range—high enough to ensure clean filling but low enough to minimize total liquid contraction. After pouring and cooling, sample shell castings were subjected to rigorous inspection. Non-destructive testing via X-ray radiography revealed no internal shrinkage defects in the critical areas. Furthermore, destructive testing involving sectioning of the castings through the major hot spot confirmed complete soundness, with a dense, shrinkage-free structure meeting and exceeding the ASTM E446 Grade 2 requirement. The successful validation proved that the integrated approach of analytical design, simulation, and controlled foundry practice could consistently produce high-integrity differential housing shell castings.

Reflecting on this project, the successful production of complex, thick-section shell castings in ductile iron hinges on a holistic understanding of the interplay between geometry, material behavior, and process physics. The key takeaways are particularly relevant for shell castings. The strategic use of a hybrid gating system with multiple flat ingates promotes thermal uniformity, reducing the number of isolated hot spots. For the inevitable major hot spots characteristic of shell castings, exothermic-risers with precisely calculated necks provide a robust feeding solution that works in harmony with ductile iron’s expansion. Numerical simulation is not just a verification tool but a powerful design optimizer that can predict defect formation in shell castings before any metal is poured, saving significant time and cost. Finally, coupling a sound design with controlled metallurgy (graphitization potential) and robust molding (high rigidity) is essential to unlock the full self-feeding potential of ductile iron, thereby achieving the highest levels of internal soundness in demanding shell castings. This comprehensive methodology, from CAD to poured casting, forms a reliable framework for tackling present and future challenges in the production of high-performance shell castings for the automotive and heavy machinery sectors.

To further generalize the principles, the feeding demand for any shell casting can be modeled by considering its geometry-modulus distribution. The modulus \( M \) at any point in a casting is a primary driver of solidification time. For a spherical hot spot, the solidification time \( t_s \) is related to the modulus by Chvorinov’s rule:

$$ t_s = k \cdot M^n $$

Where \( k \) and \( n \) are constants dependent on the metal and mold materials. For efficient feeding in shell castings, the riser modulus \( M_R \) should satisfy:

$$ M_R \geq 1.2 \cdot M_C $$

Where \( M_C \) is the modulus of the casting section being fed. In our case, for the exothermic riser with higher efficiency, the factor can be slightly reduced. The gating design also follows fluid dynamics principles. The initial sprue velocity \( v_s \) at the choke is given by Torricelli’s theorem:

$$ v_s = \mu \sqrt{2g H_p} $$

And the flow rate \( Q \) is:

$$ Q = A_{\text{choke}} \cdot v_s = \frac{G_L}{\rho_L t} $$

These formulas interconnect the key design variables. For foundries producing a variety of shell castings, maintaining a database of successful gating and feeding ratios specific to different weight ranges and section thicknesses can accelerate process development. The continuous evolution of simulation software also allows for more sophisticated analyses, including coupled fluid flow, solidification, and stress modeling, which will further enhance the predictability and quality of complex shell castings in the years to come. The journey of optimizing each shell casting process reinforces the notion that casting is both a science and an art, where empirical knowledge and computational power merge to create reliable, high-performance components.