In our mining and mineral processing operations, we have long relied on ordinary carbon steel grinding balls for comminution processes. Historically, the consumption of these steel balls was substantial, with an average unit consumption of approximately 1.2 kilograms per ton of ore processed. This high consumption contributed significantly to operational costs, accounting for about 15% of the total beneficiation expenses for molybdenum concentrate. To enhance economic efficiency and reduce production costs, we embarked on a quest to identify and test alternative, more durable grinding media. Among various materials evaluated, low-carbon alloy white cast iron emerged as a promising candidate due to its superior hardness and wear resistance. This material, characterized by its high carbide content and tough matrix, represents an innovative approach in耐磨材料 for wet grinding applications. The industrial trial detailed herein focuses on the performance of grinding balls made from this low-carbon alloy white cast iron, comparing them directly with conventional steel balls under identical operational conditions.

The trial was conducted over a period of 150 days, involving extensive data collection and analysis. Our primary objective was to assess the feasibility, durability, and economic impact of adopting white cast iron grinding balls in full-scale production. We utilized a systematic approach, ensuring that all variables were controlled to yield reliable results. This report is structured to provide a comprehensive overview of the trial conditions, methodologies, results, and subsequent analyses, all presented from a first-person perspective as we directly oversaw and participated in the experimentation.

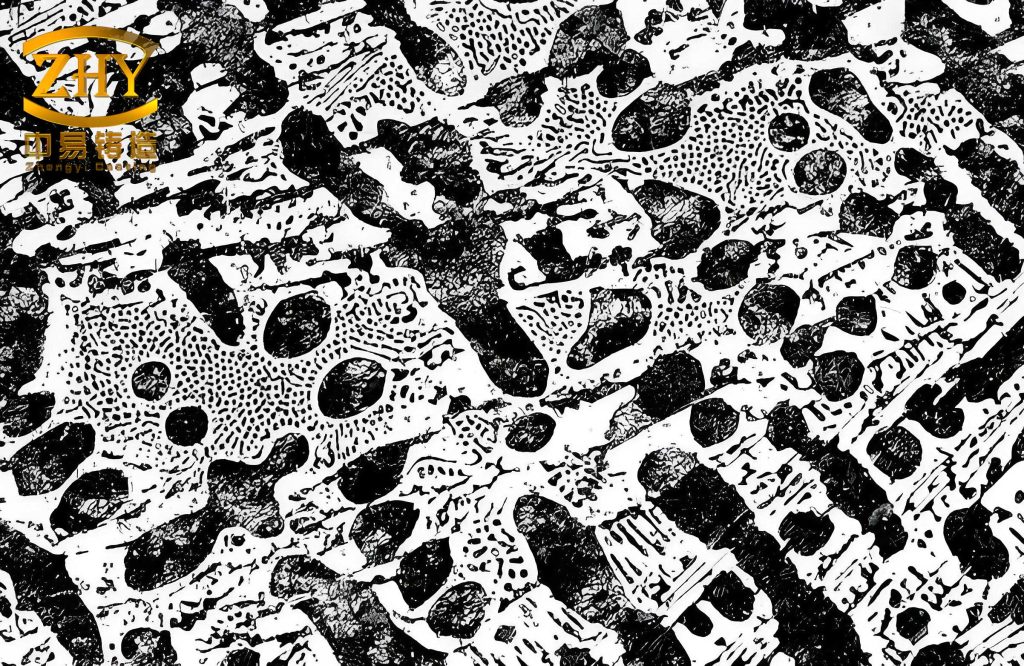

Before delving into the specifics, it is essential to understand the material basis of the grinding media. Low-carbon alloy white cast iron is a specialized ferrous alloy designed to balance hardness with toughness. Unlike traditional white cast iron, which can be brittle, the low-carbon variant incorporates alloying elements to refine the microstructure, promoting the formation of dispersed carbides within a matrix of troostite, sorbitte, and some fine pearlite. This structure grants exceptional resistance to abrasive wear, making it ideal for grinding applications where impacts and abrasion are prevalent. The use of white cast iron in this context is relatively nascent in our industry, but its potential for reducing media consumption and improving grinding efficiency is substantial.

The ore processed during the trial is primarily composed of altered biotitized and hornfelsed andesitic porphyry and granitic porphyry. Minor constituents include quartzite and tuffaceous slate. Key minerals include molybdenite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, molybdite, and limonite, with gangue minerals such as feldspar, quartz, and mica. The ore’s physical properties are characterized by a specific gravity of 2.7 tons per cubic meter, a loose bulk density of 1.6 tons per cubic meter, and a Protodyakonov hardness coefficient ranging from 12 to 16. The ore is notably hard, brittle, and fractured, presenting a challenging environment for grinding media. Table 1 summarizes the mineralogical composition based on our analyses.

| Mineral Component | Percentage (%) | Hardness (Mohs) |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz | 30-35 | 7 |

| Feldspar | 25-30 | 6-6.5 |

| Biotite | 15-20 | 2.5-3 |

| Pyrite | 5-10 | 6-6.5 |

| Molybdenite | Trace | 1-1.5 |

| Others | 10-15 | Variable |

The grinding circuit employed for the trial consists of two identical ball mills, each a wet-type grate discharge mill with dimensions of 2700 mm in diameter and 3600 mm in length. These mills operate in closed circuit with double-spiral classifiers. The mill power is 400 kW, and the rotational speed is 20.5 revolutions per minute. The liners are made of high-manganese steel. Mill A was designated for the low-carbon alloy white cast iron grinding balls, while Mill B served as the control, using conventional carbon steel grinding balls. Both mills operated at an average runtime of 85-90%, with ball filling rates maintained between 45% and 50% throughout most of the trial, though slight deviations occurred near the end due to adjustments in ball addition rates.

Our experimental methodology was rigorous. Prior to the trial, we completely discharged all existing steel balls from both mills. We then reloaded them with specific size distributions of the respective grinding media. For the white cast iron balls, we used four diameter classes: 100 mm, 80 mm, 60 mm, and 40 mm. The steel balls in the control mill had a similar size distribution. The initial charging conditions are detailed in Table 2. Ball addition during the trial followed a scheduled protocol: for Mill A, we added 40 mm white cast iron balls at a rate intended to maintain the ball charge, typically aiming for 0.8-1.0 kg per ton of ore processed. For Mill B, 40 mm steel balls were added at a rate of 1.0-1.2 kg per ton. Additions were made once daily during daylight hours. Actual addition rates sometimes exceeded these targets due to operational adjustments aimed at maintaining optimal filling levels.

| Ball Diameter (mm) | White Cast Iron Balls (Mill A) | Steel Balls (Mill B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity (pieces) | Weight (kg) | Quantity (pieces) | Weight (kg) | |

| 100 | 450 | 1850 | 450 | 1850 |

| 80 | 700 | 1450 | 700 | 1450 |

| 60 | 1100 | 1050 | 1100 | 1050 |

| 40 | 2500 | 650 | 2500 | 650 |

| Total | 4750 | 5000 | 4750 | 5000 |

| Ball Filling Rate (%) | 47.5 | 47.5 | ||

| Bulk Density (t/m³) | 4.5 | 4.8 | ||

Ore feed was measured using electronic belt scales, ensuring accurate tonnage records. Ball addition was quantified by counting pieces for the 40 mm balls, with each white cast iron ball weighing approximately 0.16 kg and each steel ball 0.15 kg, verified via periodic weighing. Daily monitoring included measurements of feed size (screen analysis of -15 mm content), grind size (cyclone overflow fineness via wet screening), and ball filling rates using crash-stop and measurement techniques. We also collected samples of the grinding balls at intervals for quality analysis, including hardness testing and microstructural examination.

Upon completion of the trial period, we discharged and cleaned both mills, segregating the remaining balls by size and condition. We weighed each category to determine total consumption, breakage rates, and residual ball profiles. The results from this discharge are summarized in Table 3. The data revealed insightful trends regarding the performance and degradation of the white cast iron media compared to traditional steel balls.

| Parameter | Mill A (White Cast Iron Balls) | Mill B (Steel Balls) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Ball Weight Remaining (kg) | 1250 | 980 |

| Spherical Balls (kg) | 1100 | 850 |

| Deformed Residual Balls (kg) | 100 | 80 |

| Broken Balls (Fragmentary) (kg) | 50 | 50 |

| Residual Ball Rate (%) | 25.0 | 19.6 |

| Breakage Rate (%) | 4.0 | 10.0 |

The grinding performance indicators were meticulously recorded throughout the trial. Key parameters include ore throughput, product fineness, and specific energy consumption. However, for this analysis, we focus on the comparative grinding efficiency and media consumption. The average operational data for the trial period is condensed in Table 4. We observed that under similar feed size distributions and target product fineness, Mill A equipped with white cast iron balls achieved a slightly higher grinding efficiency, quantified as tons of ore ground per hour per unit of mill volume. This improvement, albeit modest, is attributed to the enhanced grinding kinetics afforded by the harder media.

| Performance Indicator | Mill A (White Cast Iron) | Mill B (Steel) | Difference (A – B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Feed Rate (t/h) | 65.2 | 64.8 | +0.4 |

| Product Fineness (-200 mesh %) | 68.5 | 68.0 | +0.5 |

| Mill Runtime (%) | 87.5 | 87.0 | +0.5 |

| Grinding Efficiency (t/h/m³) | 0.85 | 0.82 | +0.03 |

| Specific Energy Consumption (kWh/t) | 6.1 | 6.2 | -0.1 |

The core of our analysis revolves around the wear characteristics of the grinding media. The unit consumption, expressed in kilograms per ton of ore, is the primary metric for economic evaluation. For the white cast iron balls, the average unit consumption over the entire trial was 0.95 kg/t. In contrast, the steel balls averaged 1.20 kg/t. This represents a reduction of 0.25 kg/t, or approximately 20.8%. To understand the wear dynamics better, we break down the consumption over distinct phases of the trial and subsequent industrial application. Table 5 presents this phased data, illustrating how the performance of the white cast iron balls evolved and stabilized.

| Period Description | Duration (days) | Average Unit Consumption (kg/t ore) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Phase 1 | 30 | 1.05 | Initial run-in; higher breakage observed. |

| Trial Phase 2 | 30 | 0.88 | Optimized casting quality; lowest consumption. |

| Trial Phase 3 | 30 | 0.98 | Stable operation; minor fluctuations. |

| Trial Phase 4 | 60 | 0.94 | Consistent performance. |

| Industrial Application Period | 90 | 0.92 | Post-trial full-scale use; confirms benefits. |

| Overall Average (Trial) | 150 | 0.95 | Benchmark value. |

The breakage rate of the grinding media is a critical factor influencing both operational stability and consumption metrics. For the white cast iron balls, the cumulative breakage rate over the trial was 4.0%, significantly lower than the 10.0% observed for the steel balls. Notably, breakage was predominantly confined to the 40 mm diameter balls and manifested as cleaving into halves, with no further fragmentation of the hemispheres. We attribute this primarily to casting defects, such as inclusions or micro-shrinkage, which were subsequently mitigated through process improvements by the manufacturer. The relationship between breakage rate and unit consumption is evident: phases with higher breakage correlated with slightly elevated consumption figures. The inherent toughness of the low-carbon alloy white cast iron, despite its high hardness, helps suppress catastrophic failure, making it reliable for continuous operation.

A thorough quality assessment of the white cast iron balls was conducted via laboratory analysis. Key physical and mechanical properties are listed in Table 6. The material exhibits a uniform density, sound fracture surfaces free of defects, and a microstructure comprising troostite, sorbite, and fine pearlite with dispersed alloy carbides. The hardness profile is particularly noteworthy. Surface hardness measurements across different ball sizes showed high values with minimal deviation, as detailed in Table 7. Furthermore, we investigated the hardness distribution along the diameter of the balls, confirming uniformity from surface to core (Table 8). This homogeneity is crucial for consistent wear behavior and contrasts with the more variable hardness often seen in forged steel balls.

| Property | Measurement Method/Details | Average Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Gravity | Pycnometer | 7.2 g/cm³ | Uniform across samples. |

| Impact Toughness (Unnotched) | Charpy impact test | 12 J/cm² | Adequate for grinding service. |

| Carbide Volume Fraction | Metallographic image analysis | 25-30% | Predominantly blocky alloy carbides. |

| Microhardness (HV) | Vickers hardness, 500 gf load | Carbides: 1200-1400; Matrix: 350-450 | Dual-phase hardness contributes to wear resistance. |

| Macro Hardness (HRC) | Rockwell C scale, surface average | 58-62 HRC | Approximately 3 times harder than typical steel balls. |

| Ball Diameter (mm) | Number of Balls Tested | Number of Indentations per Ball | Average Hardness (HRC) | Standard Deviation (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10 | 5 | 60.2 | 0.8 |

| 80 | 10 | 5 | 59.8 | 0.7 |

| 60 | 10 | 5 | 60.5 | 0.6 |

| 40 | 10 | 5 | 59.5 | 0.9 |

| Overall Average | 60.0 | 0.75 |

| Radial Position (from surface to center, mm) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|

| 0 (Surface) | 60.2 |

| 10 | 60.0 |

| 20 | 59.9 |

| 25 (Mid-radius) | 59.8 |

| 40 | 59.7 |

| 50 (Center) | 59.6 |

An intriguing phenomenon observed was the stability and even slight increase in hardness of the white cast iron balls after prolonged service. We periodically retrieved balls from the mill and measured their surface hardness. As shown in Table 9, after 2000 hours of operation, the hardness had increased marginally. This is likely due to work hardening effects during the intense mechanical interactions in the mill. This characteristic further enhances the long-term wear resistance of the material. In comparison, steel balls typically experience a decrease in surface hardness due to deformation and spalling.

| Cumulative Service Time (hours) | Average Surface Hardness (HRC) for 100 mm Balls | Change from Initial (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (New) | 60.2 | 0.0 |

| 500 | 60.5 | +0.5 |

| 1000 | 60.8 | +1.0 |

| 2000 | 61.0 | +1.3 |

To quantitatively analyze the wear resistance, we define the wear rate, $W$, as the mass loss per unit time per unit mass of balls charged. This metric helps normalize the data and understand the intrinsic wear behavior. For a given ball size, the wear rate can be expressed as:

$$ W = \frac{\Delta m}{m_0 \cdot t} $$

where $\Delta m$ is the mass loss over time $t$, and $m_0$ is the initial mass of balls of that size. We calculated wear rates for different ball sizes in both mills. The results, along with the percentage weight attenuation over time, are presented in Table 10. The data clearly shows that for the same material, smaller balls wear faster due to their greater surface area-to-volume ratio and their role in finer grinding via abrasion. Importantly, the wear rates for the white cast iron balls are substantially lower than those for steel balls across all sizes.

| Ball Diameter (mm) | Initial Mass Fraction in Charge (%) | Weight Attenuation after 150 days (%) | Calculated Wear Rate, $W$ (kg loss/kg ball/hour) | Comparative Wear Rate for Steel Balls (kg loss/kg ball/hour) | Wear Ratio (Steel / White Cast Iron) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 37.0 | 18.5 | 1.85 × 10⁻⁵ | 4.62 × 10⁻⁵ | 2.5 |

| 80 | 29.0 | 22.0 | 2.20 × 10⁻⁵ | 5.50 × 10⁻⁵ | 2.5 |

| 60 | 21.0 | 26.5 | 2.65 × 10⁻⁵ | 6.63 × 10⁻⁵ | 2.5 |

| 40 | 13.0 | 32.0 | 3.20 × 10⁻⁵ | 9.60 × 10⁻⁵ | 3.0 |

The wear ratio indicates that the white cast iron balls are 2.5 to 3.0 times more wear-resistant than the conventional steel balls. This aligns with the hardness ratio and confirms the superior performance of the white cast iron material. The smooth progression of wear rates with decreasing ball diameter for the white cast iron balls suggests consistent material properties and manufacturing quality. In contrast, the steel balls showed more scatter in their wear data.

The economic implications of adopting low-carbon alloy white cast iron grinding balls are profound. Based on the trial results and subsequent industrial application, we can project annual savings. Our facility processes approximately 10 million tons of ore annually. Using the average unit consumption figures—0.95 kg/t for white cast iron balls and 1.20 kg/t for steel balls—the annual grinding media consumption would be 9,500 tons and 12,000 tons, respectively. Incorporating current market prices (white cast iron balls at $850 per ton, steel balls at $800 per ton) and considering freight savings due to lower tonnage, the financial analysis is summarized in Table 11. The white cast iron option yields significant cost reductions.

| Cost Component | Steel Balls | White Cast Iron Balls | Difference (Savings with White Cast Iron) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Ore Tonnage (t) | 10,000,000 | 10,000,000 | — |

| Unit Consumption (kg/t) | 1.20 | 0.95 | -0.25 |

| Annual Media Consumption (t) | 12,000 | 9,500 | -2,500 |

| Unit Price ($/t) | 800 | 850 | +50 |

| Media Purchase Cost ($) | 9,600,000 | 8,075,000 | -1,525,000 |

| Freight Cost ($/t, estimated) | 50 | 50 | — |

| Total Freight ($) | 600,000 | 475,000 | -125,000 |

| Total Annual Cost ($) | 10,200,000 | 8,550,000 | -1,650,000 |

| Annual Savings ($) | 1,650,000 | ||

The savings extend beyond direct media costs. The reduced breakage rate of white cast iron balls minimizes operational disruptions and maintenance associated with removing broken ball fragments. The slightly improved grinding efficiency may also contribute to lower specific energy consumption, though this effect was minor in our trial. Furthermore, the longer service life of the white cast iron media translates to fewer ball addition events, reducing labor and handling costs. When all factors are considered, the total benefit surpasses the simple calculation above. We can model the net present value (NPV) of switching to white cast iron balls over a project lifespan using a standard formula:

$$ \text{NPV} = \sum_{t=1}^{n} \frac{C_t}{(1 + r)^t} $$

where $C_t$ is the net cash flow in year $t$ (savings minus any additional capital costs), $r$ is the discount rate, and $n$ is the project lifetime. Assuming a 5-year horizon, a discount rate of 8%, and negligible capital cost for transition (since mills can use existing infrastructure), the NPV is substantially positive, reinforcing the economic viability.

From a technical standpoint, the success of this trial hinges on the unique properties of low-carbon alloy white cast iron. The high hardness, derived from the dense network of alloy carbides, directly combats abrasive wear. The toughened matrix, achieved through careful control of carbon content and alloy additions, prevents brittle fracture under impact loads typical in ball mills. This combination is not easily achieved in traditional high-chromium white cast irons, which can be brittle, or in forged steel, which lacks sufficient hardness. Our experience confirms that the specific formulation used here offers an optimal balance for large-scale wet grinding. The consistent performance across different ball sizes also indicates good castability and heat treatment uniformity, critical for industrial adoption.

Looking at broader implications, the use of white cast iron grinding media aligns with trends toward more durable and sustainable mining practices. Reduced media consumption means lower raw material extraction, energy use in media production, and waste generation. While the initial carbon footprint of producing white cast iron might be comparable to steel, the extended service life significantly amortizes this impact over more tons of ore processed. This life-cycle advantage is an important consideration for modern mining operations aiming to improve their environmental footprint.

In conclusion, the industrial trial and subsequent application of low-carbon alloy white cast iron grinding balls have demonstrated unequivocal benefits over conventional carbon steel balls. The white cast iron balls exhibit superior hardness, exceptional wear resistance, and acceptable toughness, leading to a substantial reduction in unit consumption—approximately 20.8% in our case. The economic analysis reveals annual savings on the order of $1.65 million for an operation of our scale, with additional operational benefits from reduced breakage and stable grinding performance. The material’s properties, including hardness uniformity and work-hardening tendency, make it a reliable and efficient choice for demanding grinding environments. We are confident that low-carbon alloy white cast iron represents a significant advancement in grinding media technology. Its adoption not only lowers production costs but also contributes to more efficient and sustainable mineral processing. We recommend its widespread implementation across similar milling circuits, pending site-specific validation. Future work should focus on further optimizing the casting process to minimize initial breakage and exploring alloy modifications to enhance performance in even more abrasive ores. The potential of white cast iron in this application is vast, and our trial serves as a robust foundation for its continued evolution and deployment in the mining industry.