In my extensive experience within the foundry industry, the production of high-integrity shell castings—particularly thin-walled, complex geometries like those used in automotive applications—presents a formidable challenge. The success of such castings hinges on a meticulous integration of die design, gating system configuration, molten metal handling, and process parameter control. This article, drawn from years of hands-on practice and analysis, delves into the core principles and advanced methodologies essential for mastering the art and science of producing superior shell castings. I will focus on the synergistic relationship between die casting process design for aluminum alloy shell components and state-of-the-art melting and holding technologies, utilizing numerous tables and mathematical models to encapsulate critical relationships.

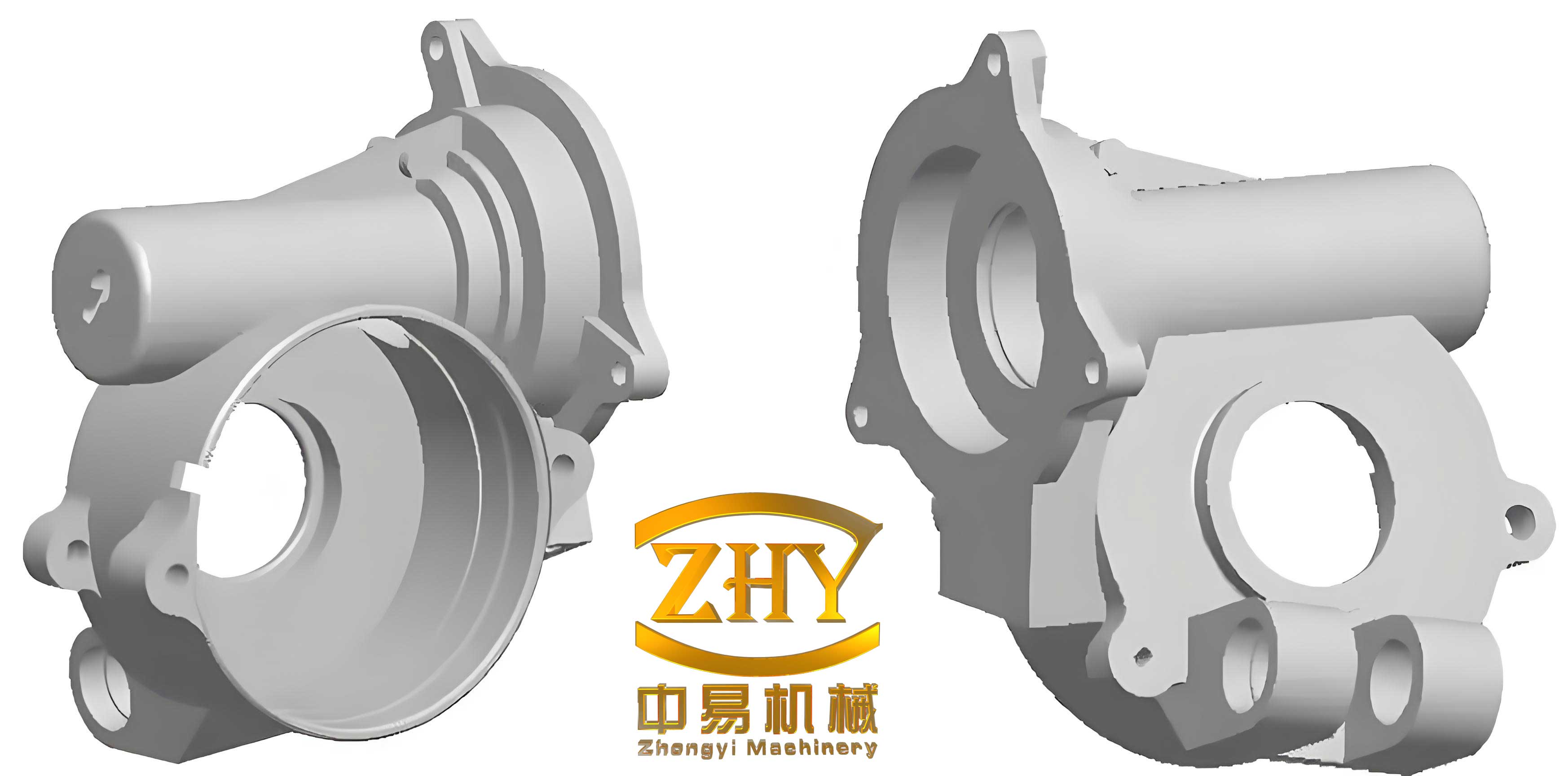

The fundamental premise is that optimal production of shell castings begins long before metal is poured. It starts with a comprehensive understanding of the component’s function, geometry, and performance requirements. A classic example is a regulator housing, a quintessential shell casting characterized by substantial planar dimensions, intricate features, and minimal, varying wall thicknesses. Such a component, often made from alloys like Al-Si8Cu3, demands not only dimensional accuracy but also pressure tightness, making the control of the filling and solidification sequence paramount. Any compromise in the initial design phase, especially regarding the gating system, is irrecoverable through subsequent adjustments to machine parameters.

My approach to designing for shell castings always prioritizes the analysis of part orientation and die parting lines. The primary goals are to facilitate mold filling, enable efficient ejection, ensure die structural integrity, and maximize die life. For a complex shell casting requiring multi-directional draft, the selection of the main parting plane is critical. Consider a component requiring release in the Z-direction and along two perpendicular X-directions. The optimal parting line should be placed to allow the machine’s opening force to handle the major stripping action, while side actions (via angled pins or hydraulic cylinders) manage the secondary directions. The key is to minimize the risk of part distortion during ejection, a common pitfall with delicate shell castings. A well-chosen parting line directly influences the stability of the die and the magnitude of the clamping force on the moving half.

The heart of shell casting die design lies in the strategic placement and sizing of the ingate. This decision is irrevocable once the die is manufactured and fundamentally dictates the flow pattern within the cavity. For deep-cavity shell castings, the ideal ingate location is often at the highest point to promote gravity-assisted filling. However, surface finish requirements may preclude this. In one specific case study involving a large, thin-shell component, initial ingate placement at one end led to persistent cold shuts and incomplete filling at the farthest point, severely limiting productivity. The metal stream was directly impinging on a deep core, causing excessive pressure loss and premature solidification. The solution was a complete redesign, relocating the ingate to the opposite end to achieve a longer but more controlled sequential filling path. This change alone increased yield dramatically, underscoring that for shell castings, a longer fill path with proper directional solidification is superior to a short, turbulent one. The fill length \( L_f \) is a critical variable, and the pressure drop \( \Delta P \) along it can be approximated by a modified Bernoulli’s equation for non-ideal flows:

$$ \Delta P = \frac{1}{2} \rho \bar{v}^2 \left( f \frac{L_f}{D_h} + K \right) $$

where \( \rho \) is the molten metal density, \( \bar{v} \) is the average flow velocity, \( f \) is the friction factor, \( D_h \) is the hydraulic diameter of the flow channel, and \( K \) represents minor loss coefficients. Minimizing \( \Delta P \) is essential for complete cavity fill in thin-shell castings.

The geometry of the ingate itself is a three-dimensional controller of metal flow. Its thickness \( d \) primarily governs the metal stream’s velocity and jet characteristics upon entry. The width \( e \) controls the volumetric flow rate in the plane of the ingate, and the attack angle \( \alpha \) directs the flow in the vertical and transverse directions. Optimizing these parameters for each unique shell casting is crucial. Based on empirical data and flow simulation validations, I have compiled standard parameter ranges for aluminum alloy shell castings of similar complexity, as shown in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Typical Range for Shell Castings | Example Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingate Thickness | \( d \) | mm | 1.5 – 3.0 | 2.1 |

| Ingate Width | \( e \) | mm | 30 – 60 | 43 |

| Ingate Attack Angle | \( \alpha \) | ° | 15 – 30 | 20 |

| Ingate Cross-Sectional Area | \( A_g \) | mm² | 70 – 120 | 90.3 |

| Fill Time | \( \tau_g \) | s | 0.05 – 0.15 | 0.0812 |

| Gate Velocity | \( v_g \) | m/s | 40 – 60 | 44.85 |

| Plunger Speed (Gate) | \( v_{p0} \) | m/s | 0.8 – 2.0 | 1.43 |

The fill time \( \tau_g \) is arguably the most critical parameter for shell castings. It must be shorter than the time for the metal to solidify at the ingate. A widely used empirical formula for estimating the fill time in die casting, particularly for thin-walled sections common in shell castings, is:

$$ \tau_g = k \cdot T_{max} \cdot \frac{(T_{pour} – T_{solidus}) + S_f}{(T_{mold} – T_{solidus})} \cdot \frac{\delta}{\delta_{min}} $$

Here, \( k \) is an alloy-specific constant, \( T_{max} \) is the maximum wall thickness, \( T_{pour} \) and \( T_{solidus} \) are the pouring and solidus temperatures, \( T_{mold} \) is the die temperature, \( S_f \) is a superheat factor, and \( \delta / \delta_{min} \) is a shape factor ratio. For the example shell casting with a dominant wall thickness of 3mm, the calculated fill time aligns with the empirical value in Table 1.

The gate velocity \( v_g \) and the corresponding plunger speed \( v_{p0} \) are derived from the continuity equation and the machine’s hydraulic characteristics. The relationship is given by:

$$ A_g \cdot v_g = A_{chamber} \cdot v_{p0} $$

where \( A_{chamber} \) is the cross-sectional area of the shot sleeve. Achieving the high gate velocities necessary to fill thin sections before freezing is a hallmark of producing sound shell castings.

Complementing the gating system is the overflow and venting design. Overflows serve to trap cold, oxidized metal at the end of fills and provide thermal mass for feeding. Vents allow air to escape, preventing back-pressure and gas entrapment within the shell casting. The sizing of these features is systematic. The total overflow volume \( V_{overflow} \) is often a percentage of the casting volume \( V_{casting} \), typically 10-25% for complex shell castings. The vent area \( A_{vent} \) is typically 20-50% of the ingate area \( A_g \) to ensure adequate exhaust without allowing metal ejection. Table 2 provides typical parameters for the exhaust system in aluminum shell castings.

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Typical Range / Formula | Example Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overflow Cross-Sectional Area | \( A_{of} \) | mm² | \( (0.5 – 0.8) \times A_g \) | 63 |

| Overflow Weight | \( G_{of} \) | g | \( (0.1 – 0.25) \times G_{casting} \) | 180 |

| Vent Cross-Sectional Area | \( A_v \) | mm² | \( (0.2 – 0.5) \times A_g \) | 54 |

The production of high-quality shell castings is not limited to die design; it is inextricably linked to the quality and consistency of the molten metal. Advanced melting and holding technology is a non-negotiable prerequisite. In my practice, utilizing energy-efficient, precisely controlled melting systems has proven indispensable for maintaining the metallurgical quality required for pressure-tight shell castings.

A prime example is the modern vertical shaft melting and holding furnace. This system integrates a melting chamber and a separate holding bath within a single vertical structure, governed by a sophisticated PLC. The core principle is counter-current heat exchange: charge material (ingots, returns) is loaded at the top and descends through a preheating zone where it is heated by the hot exhaust gases rising from the melting zone below. This design achieves remarkable thermal efficiency. The energy consumption \( E \) per ton of molten aluminum can be modeled as a function of key variables:

$$ E = C_0 + \frac{C_1 \cdot (T_{set} – T_{amb})}{\eta_{th}} + C_2 \cdot R_{returns} $$

where \( C_0, C_1, C_2 \) are system constants, \( T_{set} \) is the target holding temperature, \( T_{amb} \) is ambient temperature, \( \eta_{th} \) is the overall thermal efficiency, and \( R_{returns} \) is the fraction of recycled material in the charge. For a furnace operating with a 50/50 mix of primary and secondary aluminum and a setpoint of 720°C, specific energy consumption can be consistently held below 600 kWh per tonne, a critical factor for the cost-effective production of shell castings.

The PLC automation ensures several vital functions for shell casting production: independent control of melting and holding burners, automatic temperature regulation in the holding bath, pre-programmed furnace lining sintering cycles, and crucially, automated charge feeding based on exhaust gas temperature monitoring. When the exhaust temperature at the top reaches a set limit (e.g., 300°C), it signals a low charge level in the melting shaft, triggering the automatic feeder to add new material. This maintains a consistent thermal mass in the shaft, stabilizing the preheating process and ensuring a steady supply of molten metal at the correct temperature for casting shell components. The holding bath’s temperature uniformity, often within ±5°C, is vital for achieving consistent fill characteristics and microstructure in thin-walled shell castings.

The interplay between melting technology and casting parameters can be formalized. The superheat \( \Delta T_{sh} \) available at the die is:

$$ \Delta T_{sh} = T_{delivery} – T_{liquidus} = (T_{hold} – \Delta T_{transport} – \Delta T_{ladle}) – T_{liquidus} $$

A stable, accurately controlled \( T_{hold} \) from the furnace minimizes variations in \( \Delta T_{sh} \), which directly impacts fluidity and fill time calculations for shell castings. This stability is a cornerstone of repeatable quality.

Beyond the furnace, quantitative dosing systems are essential for high-pressure die casting of shell castings. Precise shot control requires knowing the exact volume of metal delivered to the shot sleeve. The mass \( m_{shot} \) required for a shell casting and its overflows is given by:

$$ m_{shot} = \rho \cdot (V_{casting} + V_{overflows} + V_{biscuit}) $$

Advanced dosing furnaces use weigh cells or electromagnetic pumps to deliver this mass with an accuracy of ±0.5%, eliminating another source of variation in the production of shell castings.

To synthesize these concepts, let’s consider an integrated process model for a shell casting. The goal is to determine the required machine settings. We define the following variables: casting weight \( W_c \), fill time \( \tau \), gate area \( A_g \), plunger diameter \( D_p \), and slow-shot plunger speed \( v_{slow} \). The fast-shot plunger speed \( v_{fast} \) is determined by the gate velocity requirement. A two-stage injection profile is standard. The model involves solving a system of equations:

1. Volume continuity from sleeve to gate: \( \frac{\pi D_p^2}{4} \cdot v_{fast} = A_g \cdot v_g \).

2. Fill time definition: \( \tau = \frac{V_{cavity}}{A_g \cdot v_g} \).

3. Hydraulic power model relating machine pressure to plunger force.

These can be combined to select an appropriate machine. For instance, rearranging gives the required gate area for a target fill time and gate velocity:

$$ A_g = \frac{V_{cavity}}{v_g \cdot \tau} $$

And the corresponding fast-shot plunger speed is:

$$ v_{fast} = \frac{4 A_g v_g}{\pi D_p^2} $$

Table 3 provides a calculated example for a family of aluminum shell castings with varying projected areas.

| Casting Projected Area (cm²) | Cavity Volume (cm³) | Target Fill Time (ms) | Calculated Gate Area (mm²) | Required Plunger Speed (m/s) for D_p=70mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 250 | 400 | 80 | 83.3 | 2.17 |

| 350 | 560 | 90 | 103.7 | 2.70 |

| 450 | 720 | 100 | 120.0 | 3.12 |

The mechanical properties of the final shell casting, such as tensile strength \( \sigma_t \) and elongation \( \epsilon \), are functions of the microstructure, which is governed by solidification conditions. The secondary dendrite arm spacing (SDAS), \( \lambda_2 \), a key microstructural parameter, is related to the local solidification time \( t_f \) by:

$$ \lambda_2 = a \cdot t_f^n $$

where \( a \) and \( n \) are alloy constants. The local solidification time is heavily influenced by the die temperature and the cooling rate, which in turn depends on the fill pattern and die thermal management. For thin-walled shell castings, achieving a fine, uniform microstructure is challenging due to rapid cooling, making controlled fill and thermal die design even more critical.

In conclusion, the reliable and economical production of high-performance shell castings is a multi-disciplinary endeavor. It demands a holistic view that seamlessly connects advanced die design principles—with rigorous optimization of parting lines, ingate geometry, and venting systems—to state-of-the-art metal preparation and handling technologies. Every parameter, from the attack angle of an ingate to the exhaust temperature setpoint in a melting furnace, plays a interconnected role in determining the quality, integrity, and cost of the final shell casting. The formulas and tables presented here serve as a foundational toolkit. However, successful implementation requires iterative refinement through simulation and practical validation. The future of shell casting production lies in the deeper integration of these process models into real-time control systems, further pushing the boundaries of complexity, performance, and sustainability for these essential components.