In my experience with manufacturing aluminum alloy components, particularly shell castings used in aerospace and automotive applications, heat treatment processes are critical for achieving desired mechanical properties. However, defects such as surface cracks can severely compromise product quality and delivery schedules. This article delves into a case study involving ZL208 aluminum alloy shell castings, where heat treatment-induced cracks were a persistent issue. Through systematic investigation, we identified the root cause and implemented effective solutions, emphasizing the importance of transfer time during quenching. The insights gained are broadly applicable to complex, thin-walled shell castings, where thermal stress management is paramount.

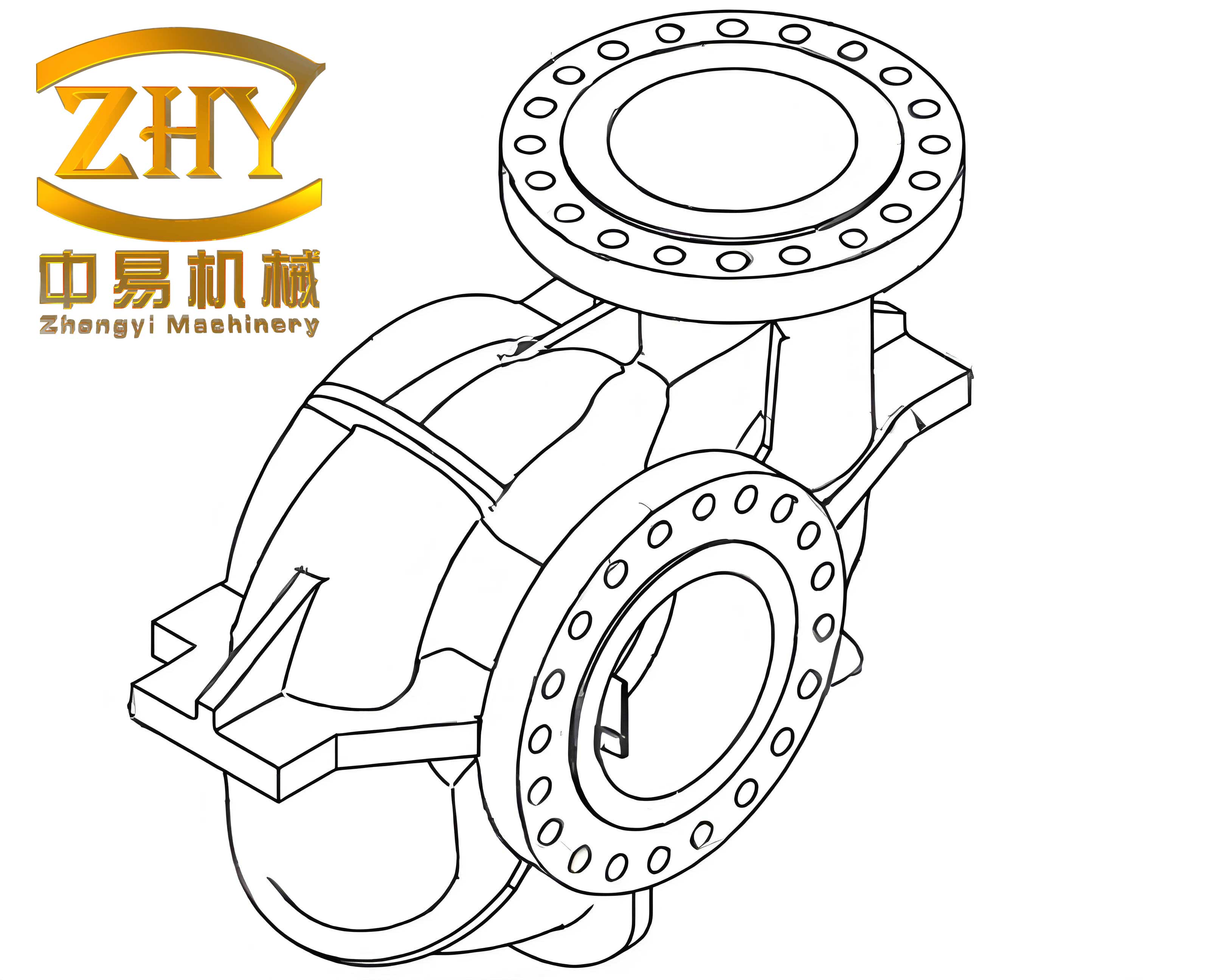

Shell castings, due to their intricate geometries and varying wall thicknesses, are prone to stress concentrations during thermal processing. The specific shell castings in question were produced via manual pattern molding using clay sand, with gravity pouring. The material, ZL208, is a cast aluminum alloy known for its high strength and corrosion resistance, often employed in structural components. The heat treatment regimen involved solution treatment followed by aging, conducted in pit-type furnaces. Mechanical properties required were tensile strength (σb) ≥ 216 MPa and yield strength (σ0.2) ≥ 190 MPa. Notably, these shell castings operate in environments not directly exposed to air, which relaxes some corrosion constraints but heightens the need for defect-free surfaces, as cracks can lead to catastrophic failures under load.

The problem emerged post-heat treatment: over 90% of shell castings exhibited severe surface cracks at specific locations, primarily near thicker sections or junctions. This high rejection rate threatened production timelines and cost-effectiveness. Initial inspections, including fluorescent testing, confirmed that cracks were absent before heat treatment, pointing to the quenching phase as the culprit. Understanding this phenomenon requires a deep dive into the thermodynamics of quenching and material response, which we explored through comparative experiments and theoretical analysis.

To isolate variables, we conducted a controlled experiment with shell castings from the same production batch. Twenty-four castings were fluorescent-tested pre-heat treatment and randomly divided into two groups of twelve each. Both groups underwent identical solution treatment at 542°C but differed in transfer time—the interval between furnace extraction and immersion in the quenching medium (water at 95°C). Results are summarized in Table 1.

| Group | Number of Shell Castings | Water Temperature (°C) | Transfer Time (s) | Cracked Castings Post-Treatment | Acceptable Castings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 95 | 5 | 8 | 4 |

| 2 | 12 | 95 | 20 | 0 | 12 |

This stark contrast indicated that shorter transfer times exacerbated cracking, prompting a mechanistic analysis focused on thermal stresses. In aluminum alloys like ZL208, solution treatment involves dissolving strengthening phases into the solid solution, and subsequent quenching aims to retain this supersaturated state. During cooling, two primary stresses arise: transformational stress (due to phase changes) and thermal stress (due to temperature gradients). For aluminum shell castings, phase transformations are minimal during quenching; thus, thermal stress dominates crack initiation. Thermal stress (σ_th) can be approximated by:

$$ \sigma_{th} = E \alpha \Delta T $$

where E is Young’s modulus, α is the coefficient of thermal expansion, and ΔT is the temperature difference between the surface and core or, in this context, between the casting temperature and quenching medium. A larger ΔT induces higher stresses, potentially exceeding the material’s fracture toughness at stress concentrators like notches or thick-thin transitions.

The temperature difference ΔT is influenced by quenching medium temperature and casting temperature upon immersion. For shell castings, water temperature was maintained at 95°C (near boiling), leaving little room for adjustment. Therefore, we focused on casting temperature at quenching, which depends on transfer time via Newton’s law of cooling. The relationship is expressed as:

$$ \frac{t – t_f}{t_i – t_f} = e^{-\frac{hA\tau}{V\rho C_p}} $$

Here, t is the casting temperature at immersion (°C), t_f is ambient temperature (°C), t_i is furnace temperature (542°C), h is the overall heat transfer coefficient (175 kcal/m²·h·°C), A is surface area (214150 mm²), V is volume (823706 mm³), ρ is density (2.7 g/cm³), C_p is specific heat (0.216 cal/g·°C), and τ is transfer time (s). Rearranging for t:

$$ t = t_f + (t_i – t_f) e^{-\frac{hA\tau}{V\rho C_p}} $$

Substituting values for these shell castings, with hA/(VρC_p) ≈ 0.025 s⁻¹, we derive:

$$ t = t_f + (542 – t_f) e^{-0.025\tau} $$

This equation highlights how transfer time τ affects t, and consequently ΔT = t – 95°C. Table 2 computes t for various τ and ambient temperatures, demonstrating that longer transfer times reduce t significantly, thereby lowering ΔT and thermal stress.

| Ambient Temperature, t_f (°C) | Transfer Time, τ (s) | Casting Temperature, t (°C) | Temperature Difference, ΔT = t – 95°C (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 5 | 474.5 | 379.5 |

| 15 | 15 | 386.5 | 291.5 |

| 15 | 25 | 316.0 | 221.0 |

| 30 | 5 | 476.0 | 381.0 |

| 30 | 15 | 390.6 | 295.6 |

| 30 | 25 | 321.0 | 226.0 |

| 45 | 5 | 477.4 | 382.4 |

| 45 | 15 | 394.7 | 299.7 |

| 45 | 25 | 327.8 | 232.8 |

For instance, at t_f = 30°C, increasing τ from 5 s to 20 s reduces ΔT by approximately 122°C (from 381°C to 259°C). This reduction is crucial because thermal stress scales linearly with ΔT. In shell castings, locations with thicker sections, such as mounting bosses or rib intersections, cool slower during transfer, resulting in higher local t and ΔT upon quenching. These areas, coupled with geometric stress concentrators, become prime sites for crack initiation, as observed in the problematic shell castings.

Beyond stress analysis, we must consider metallurgical impacts of extended transfer times. For aluminum alloys, rapid quenching is typically advocated to suppress precipitation and maximize strength after aging. However, for thin-walled shell castings with uniform sections (max wall thickness 10 mm, local pads 16.5 mm), slower cooling during transfer may not compromise solute retention severely. The governing factor is the critical cooling rate to avoid undesirable phase formation. For ZL208, which contains copper, magnesium, and other elements, the time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagram indicates that precipitation kinetics are relatively sluggish above 300°C. Thus, transfer times up to 25 s allow t to drop to around 320°C, still above the nose of the TTT curve, ensuring sufficient supersaturation.

To validate this, we conducted extensive process trials with shell castings, varying transfer times from 18 to 25 s. Each batch was fluorescent-tested post-heat treatment, and mechanical properties were evaluated. Results are consolidated in Table 3, showing that transfer times of 20 s or more eliminated cracks entirely, while shorter times still caused sporadic defects.

| Trial Batch | Transfer Time, τ (s) | Number of Shell Castings Tested | Crack-Free Castings | Rejection Rate (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 10 | 9 | 10 | One casting cracked at thick section |

| 2 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 10 | Similar crack location |

| 3 | 20 | 13 | 13 | 0 | No defects observed |

| 4 | 20 | 17 | 17 | 0 | Consistent performance |

| 5 | 22 | 11 | 10 | 9 | Minor crack in one unit |

| 6 | 22 | 16 | 16 | 0 | All shell castings acceptable |

| 7 | 25 | 12 | 12 | 0 | Optimal for this geometry |

Mechanical testing confirmed that properties remained within specifications. Figure 1 and Figure 2 plot tensile strength (σb) and yield strength (σ0.2) for samples from trials 3 and 7, demonstrating that all values exceed 216 MPa and 190 MPa, respectively. This aligns with the premise that for shell castings with moderate wall thicknesses, transfer times can be extended without sacrificing strength, provided the alloy’s precipitation behavior is considered.

$$ \text{Figure 1: Tensile strength (σb) distribution for shell castings with τ = 20 s and τ = 25 s. All points above 216 MPa threshold.} $$

$$ \text{Figure 2: Yield strength (σ0.2) distribution for shell castings with τ = 20 s and τ = 25 s. All points above 190 MPa threshold.} $$

The success of this approach hinges on quantifying the heat transfer dynamics specific to shell castings. The dimensionless Biot number (Bi) helps assess internal temperature gradients:

$$ Bi = \frac{h L_c}{k} $$

where L_c is characteristic length (volume/surface area ≈ 3.85 mm for these shell castings) and k is thermal conductivity (~120 W/m·K for ZL208). With h ≈ 200 W/m²·K (converted from 175 kcal/m²·h·°C), Bi ≈ 0.0064, indicating that internal resistance is negligible compared to surface convection—lumped capacitance applies. Thus, temperature is uniform within the casting during transfer, validating the use of Newton’s law. However, upon water immersion, high convective coefficients (5000-10000 W/m²·K for boiling water) increase Bi, creating steep surface-to-core gradients that drive thermal stress. By reducing initial ΔT, we mitigate these gradients.

Further, we can model thermal stress evolution using thermoelastic theory. For a spherical shell analogy (relevant for curved sections in shell castings), the stress at the surface σ_s is:

$$ \sigma_s = \frac{E \alpha}{1 – \nu} \left( \frac{1}{r_o^3 – r_i^3} \int_{r_i}^{r_o} \Delta T(r) r^2 dr – \Delta T(r_o) \right) $$

where ν is Poisson’s ratio, r_i and r_o are inner and outer radii, and ΔT(r) is temperature difference from reference. For solid sections, this simplifies to:

$$ \sigma_s \propto E \alpha \Delta T_{avg} $$

where ΔT_{avg} is average temperature difference. In practice, finite element analysis (FEA) simulations of shell castings during quenching reveal that stress peaks at fillets and thickness transitions, correlating with crack observations. By inputting temperature-dependent material properties and boundary conditions, FEA can optimize transfer times for diverse shell casting geometries.

In industrial settings, implementing extended transfer times requires logistical adjustments. For shell castings processed in batches, furnace-to-quench distances may need extension, or automated transfer systems can be programmed with controlled delays. It’s vital to monitor ambient temperature variations, as our formula shows t_f influence is minor but non-zero. Seasonal changes might necessitate slight τ adjustments—for example, in colder environments, longer transfer times could be needed to achieve the same t. We recommend real-time infrared pyrometry to measure casting temperature before quenching, enabling dynamic τ control for consistent ΔT.

Another aspect is quenchant selection. While water is effective for aluminum shell castings, polymer quenchants or air mist can offer milder cooling, reducing thermal stress. However, for ZL208, which requires moderate cooling rates for strength, water at 95°C remains suitable. Additives like corrosion inhibitors may be beneficial, though not essential for non-exposed shell castings. The key is balancing quench severity with stress minimization, as encapsulated by the quench factor (Q) model:

$$ Q = \int_{0}^{t} \frac{dt}{C(T)} $$

where C(T) is the critical time at temperature T to precipitate a specific fraction. For shell castings, prolonging transfer time alters the Q integral, but within allowable limits for mechanical properties.

Beyond ZL208, these principles apply to other aluminum alloys used in shell castings, such as A356 or 319. Each alloy has unique precipitation kinetics, necessitating tailored transfer times. For instance, high-silicon alloys may tolerate longer transfers due to slower diffusion. Empirical studies on various shell casting geometries—from turbine housings to pump bodies—show that optimal τ ranges from 15 to 30 s for wall thicknesses of 5-20 mm. This underscores the generality of our findings.

In quality assurance, non-destructive testing (NDT) like fluorescent penetrant inspection remains essential for detecting sub-surface cracks in shell castings. However, preventive measures through process optimization are more cost-effective. Statistical process control (SPC) charts for transfer time and crack incidence can help maintain robustness. We advocate for design-for-manufacturing guidelines: uniform wall thicknesses, generous fillets, and avoidance of abrupt section changes in shell castings to inherently lower stress concentrations.

In conclusion, the crack defect in ZL208 aluminum alloy shell castings was primarily due to excessive thermal stress from short transfer times during quenching. By extending transfer time to 20-25 s, we reduced the temperature difference between casting and quenchant, thereby lowering stress below the cracking threshold. Mechanical properties were preserved because the alloy’s precipitation kinetics allowed sufficient solute retention. This case study highlights that for complex, thin-walled shell castings, thermal stress management via controlled cooling delays is a viable strategy. Future work could explore integrated modeling of heat transfer, phase transformations, and stress to develop predictive tools for shell casting heat treatment optimization.

Ultimately, the longevity and reliability of shell castings in critical applications depend on meticulous process design. As industries demand lighter and stronger components, aluminum alloy shell castings will continue to be pivotal, and addressing heat treatment challenges will remain at the forefront of manufacturing excellence.