In the field of advanced manufacturing, particularly for automotive and engineering applications, the demand for high-integrity aluminum-silicon alloy components has surged. These shell castings are critical due to their complex geometries, thin walls, and stringent requirements for mechanical strength and pressure tightness. My extensive involvement in foundry technology has revealed that traditional gravity casting methods often fall short for such shell castings, leading to defects like oxide inclusions, porosity, shrinkage, and gas holes. This prompted a shift to low-pressure casting, a process that has revolutionized the production of Al-Si shell castings by ensuring superior density, airtightness, and performance. In this article, I will elaborate on the application of low-pressure casting for Al-Si shell castings, drawing from practical experiences to highlight key parameters, simulations, and operational insights, with an emphasis on optimizing the process for mass production.

The transition to low-pressure casting was driven by persistent issues in gravity casting of shell castings. For instance, in producing an engineering vehicle component—a complex Al-Si alloy shell casting with dimensions of approximately 450 mm × 585 mm × 315 mm, a weight of around 50 kg, and varying wall thicknesses up to 60 mm—gravity casting resulted in unacceptable defect rates. These shell castings, made of ZL111 alloy, required pressure tightness up to 0.3 MPa for 15 minutes without leakage, but defects compromised quality. Common problems included oxide slag entrapment, gas pores, and micro-shrinkage, which were exacerbated by turbulent filling and inadequate feeding. Low-pressure casting emerged as a viable solution, offering controlled filling and solidification under pressure, thereby enhancing the integrity of shell castings.

To understand the benefits, let’s compare the two processes. In gravity casting, the molten metal flows freely into the mold, often causing turbulence that leads to oxidation and gas entrapment. For shell castings with intricate designs, this can result in localized defects, especially in thick sections. In contrast, low-pressure casting uses a pressurized system to lift molten aluminum from a furnace into the mold cavity via a riser tube. This bottom-filling approach minimizes turbulence, reduces oxide formation, and promotes directional solidification, which is crucial for shell castings. The process parameters are meticulously controlled, as summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Range or Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Casting Temperature | 680°C – 710°C | Optimal for fluidity while minimizing gas absorption |

| Filling Pressure | 0.12 MPa – 0.16 MPa | Calculated based on metallostatic head and system losses |

| Filling Time | 15 s – 30 s | Balances mold filling and gas evacuation |

| Solidification Pressure | 0.13 MPa – 0.16 MPa | Slightly higher than filling pressure for effective feeding |

| Pressure Increase Rate | 0.003 MPa/s – 0.006 MPa/s | Ensures smooth transition to solidification phase |

| Pressure Holding Time | 10 min – 15 min | Allows complete solidification and feeding |

The filling pressure in low-pressure casting is derived from Pascal’s principle, which relates pressure to the height of the molten metal column. The formula is given by:

$$P = \mu H \rho g$$

where \(P\) is the filling pressure in MPa, \(\mu\) is a system efficiency factor (typically 0.8–1.0 for shell castings), \(H\) is the height difference between the metal level and the mold cavity in meters, \(\rho\) is the density of Al-Si alloy (approximately 2700 kg/m³ for ZL111), and \(g\) is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s²). For the shell castings in question, with \(H \approx 0.5 \, \text{m}\) and \(\mu = 0.9\), the calculated pressure is around 0.12 MPa, aligning with the empirical range. This pressure ensures a steady fill without excessive velocity, reducing the risk of defects in shell castings.

Beyond pressure, the filling speed is critical. Too fast, and air entrapment occurs; too slow, and cold shuts may form. The filling time \(t_f\) can be estimated using the mold cavity volume \(V\) and the flow rate \(Q\) controlled by pressure. For shell castings with complex geometries, a balanced approach is adopted. The relationship is often expressed as:

$$t_f = \frac{V}{Q} \quad \text{with} \quad Q = A \sqrt{\frac{2P}{\rho}}$$

where \(A\) is the cross-sectional area of the gating system. In practice, for these shell castings, a filling time of 15–30 seconds proved optimal, allowing gradual mold filling while maintaining thermal gradients for sound solidification.

The solidification phase in low-pressure casting is where the process excels for shell castings. By applying a sustained pressure during crystallization, the molten metal is forced into shrinkage voids, enhancing density. The solidification pressure \(P_s\) is typically 10–20% higher than the filling pressure, as shown in Table 1. This pressure compensates for solidification shrinkage, which can be modeled using the Chvorinov’s rule for solidification time \(t_s\):

$$t_s = k \left( \frac{V}{A_s} \right)^2$$

where \(k\) is a constant dependent on mold material and alloy properties, \(V\) is the volume of the casting, and \(A_s\) is the surface area. For Al-Si shell castings, the modulus \(\frac{V}{A_s}\) influences feeding requirements. Low-pressure casting reduces the need for extensive risers, as pressure feeds the entire casting, leading to a higher yield—often above 85% for shell castings compared to 60–70% in gravity casting.

To validate the process, numerical simulation plays a pivotal role. Using solidification simulation software, such as HuaZhu CAE, the thermal behavior of shell castings during low-pressure casting can be analyzed. The governing heat transfer equation during solidification is:

$$\rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + L \frac{\partial f_s}{\partial t}$$

where \(T\) is temperature, \(t\) is time, \(\rho\) is density, \(c_p\) is specific heat, \(k\) is thermal conductivity, \(L\) is latent heat of fusion, and \(f_s\) is solid fraction. Simulations for these shell castings showed that low-pressure casting promotes sequential solidification from the top downward, minimizing hot spots and shrinkage. The results indicated that liquid fraction distribution remained uniform, with no isolated liquid pools, ensuring dense shell castings. This simulation-guided approach allowed for optimization of gating design and cooling placements, crucial for complex shell castings.

The gating system in low-pressure casting for shell castings is typically open and bottom-fed, as illustrated in the process schematic. This design minimizes turbulence and oxide inclusion. The gating ratio (sprue:runner:gate) is often set to 1:2:4 for Al-Si alloys to ensure smooth flow. For shell castings with thick sections, chill plates are strategically placed to control solidification rates. The use of resin sand molds enhances dimensional stability and surface finish for shell castings. Key operational requirements include:

- Mold Preparation: Vent holes of 3 mm diameter are placed at high points and dead zones to evacuate gases.

- Chill Management: Chill plates must be clean and preheated to remove moisture, preventing gas generation.

- Coatings: Two layers of refractory coating are applied to mold surfaces to improve thermal resistance and reduce sand interaction.

- Assembly and Pouring: Molds are assembled promptly before casting to minimize moisture absorption, with immediate pouring after closing.

- Melting Control: Strict adherence to melting protocols reduces hydrogen pickup and oxide formation in Al-Si alloys for shell castings.

These steps ensure that shell castings produced via low-pressure casting meet high-quality standards.

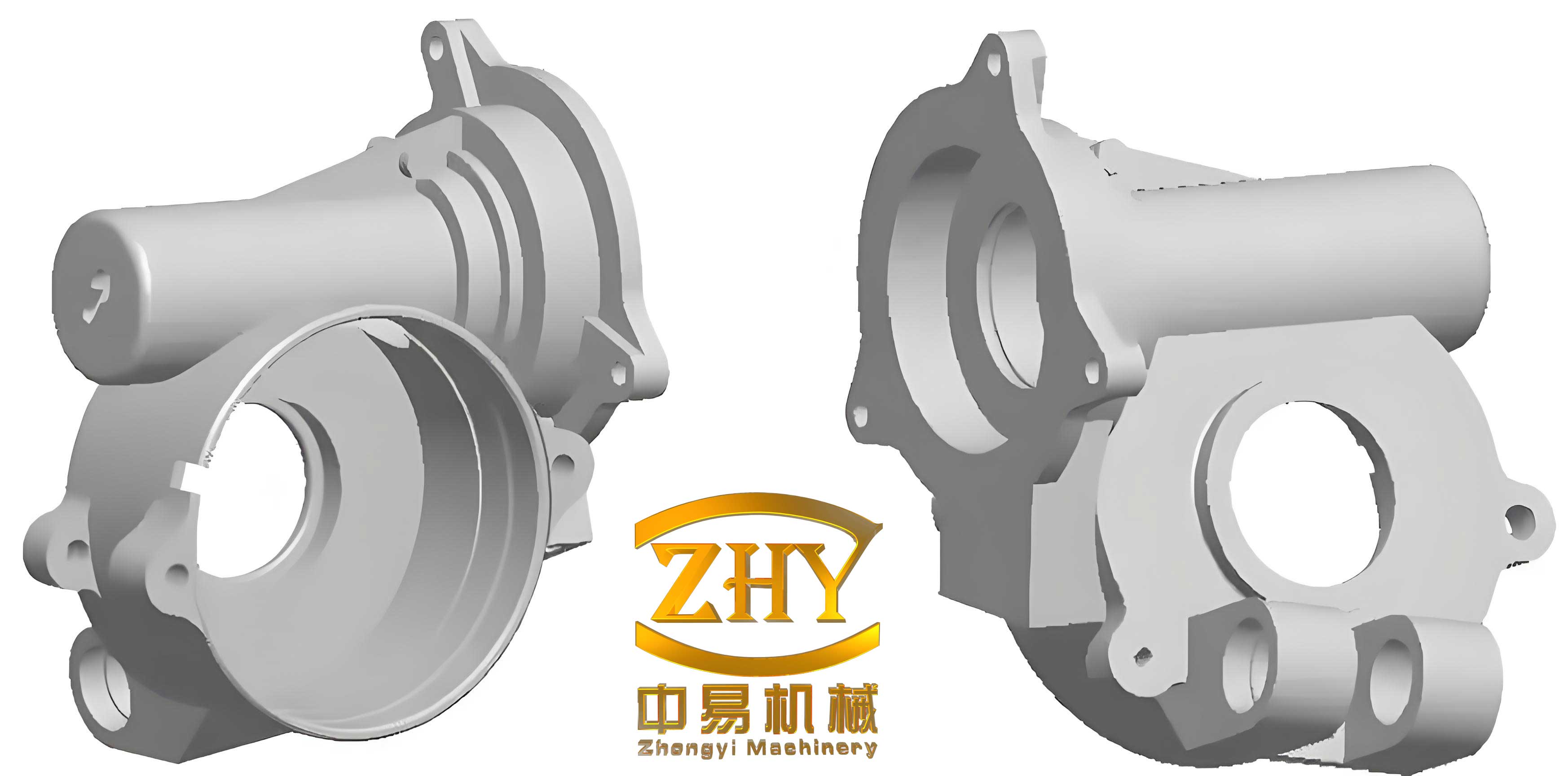

The effectiveness of this approach is evident in the final products. The shell castings exhibit a compact microstructure, with reduced porosity and improved mechanical properties. Tensile strength often exceeds 300 MPa for ZL111 alloy, with elongation above 2%, meeting or surpassing specifications. Pressure testing confirms airtightness, with no leaks at 0.3 MPa. To visually appreciate the quality, consider the following image of a successfully produced shell casting using low-pressure casting:

This image demonstrates the integrity and surface finish achievable with low-pressure casting for shell castings, highlighting the absence of defects like shrinkage or gas holes.

In terms of production scalability, low-pressure casting has enabled mass manufacturing of these shell castings. The process consistency reduces scrap rates to below 5%, compared to over 30% in gravity casting. The economic benefits include lower material usage due to reduced gating systems and higher yield. Moreover, the environmental impact is minimized through efficient energy use and less waste. For shell castings in automotive applications, this translates to reliable performance under harsh conditions, such as in engine blocks or transmission housings.

To further elaborate on the technical nuances, let’s delve into the metallurgical aspects of Al-Si shell castings under low-pressure casting. The Al-Si alloy, particularly ZL111, has a narrow freezing range, which favors feeding under pressure. The eutectic composition around 12% Si enhances fluidity and reduces hot tearing. The pressure during solidification alters the nucleation and growth kinetics, leading to finer grains. The relationship between pressure \(P\) and grain size \(d\) can be approximated by:

$$d = d_0 \exp\left(-\frac{P}{P_c}\right)$$

where \(d_0\) is the grain size at atmospheric pressure and \(P_c\) is a critical pressure constant. For shell castings, this refinement improves toughness and fatigue resistance.

Another advantage is the reduction of oxide inclusions. In low-pressure casting, the molten metal flows upward in a laminar manner, minimizing surface agitation. The oxide film formation tendency in Al-Si alloys is high, but controlled filling reduces entrapment. The amount of oxides \(\Delta O\) can be modeled as:

$$\Delta O = k_o \int v^2 \, dt$$

where \(k_o\) is an oxidation constant and \(v\) is the flow velocity. By keeping \(v\) low through pressure regulation, \(\Delta O\) is minimized for shell castings.

Table 2 summarizes the comparative benefits of low-pressure casting over gravity casting for Al-Si shell castings, based on empirical data from production runs.

| Aspect | Gravity Casting | Low-Pressure Casting |

|---|---|---|

| Defect Rate (Porosity) | High (15–20%) | Low (2–5%) |

| Oxide Inclusions | Significant | Minimal |

| Mechanical Strength | Variable, often below spec | Consistent, above spec |

| Pressure Tightness | Often fails at 0.3 MPa | Reliable up to 0.5 MPa |

| Yield (Material Efficiency) | 60–70% | 85–90% |

| Production Cost per Unit | Higher due to scrap | Lower with scale |

The simulation insights also guide optimization. For instance, the pressure curve during low-pressure casting for shell castings is designed as a multi-stage profile: slow rise for lift-off, moderate increase for filling, and a plateau for solidification. This profile can be expressed as:

$$P(t) =

\begin{cases}

P_r \cdot t & \text{for } 0 \leq t < t_1 \\

P_f & \text{for } t_1 \leq t < t_2 \\

P_s & \text{for } t_2 \leq t < t_3

\end{cases}$$

where \(P_r\) is the ramp rate, \(P_f\) is the filling pressure, and \(P_s\) is the solidification pressure. For shell castings, typical values are \(t_1 = 5 \, \text{s}\), \(t_2 = 30 \, \text{s}\), and \(t_3 = 600 \, \text{s}\), ensuring complete processing.

In practice, the implementation of low-pressure casting for shell castings requires attention to equipment calibration. The pressure control system must be precise, with feedback loops to adjust for variations in metal level and temperature. The furnace design, often a resistance or induction type, maintains a consistent temperature gradient. For Al-Si shell castings, degassing treatments using argon or nitrogen are integrated to further reduce hydrogen content, with the solubility of hydrogen in aluminum given by Sieverts’ law:

$$[H] = k_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}}$$

where \([H]\) is the hydrogen concentration, \(k_H\) is a temperature-dependent constant, and \(P_{H_2}\) is the partial pressure of hydrogen. Under low-pressure casting conditions, \(P_{H_2}\) is controlled to minimize porosity in shell castings.

The quality assurance for shell castings involves non-destructive testing like X-ray radiography and ultrasonic inspection. These methods detect internal defects that could compromise performance. Statistical process control charts are used to monitor key parameters, ensuring that each batch of shell castings meets standards. The data often shows a narrow distribution of properties, affirming process stability.

Looking ahead, advancements in low-pressure casting for shell castings include integration with additive manufacturing for mold making, real-time monitoring using IoT sensors, and AI-driven optimization of pressure profiles. These innovations promise to further enhance the quality and efficiency of producing complex shell castings.

In conclusion, the adoption of low-pressure casting for Al-Si shell castings has proven transformative in foundry operations. By leveraging controlled pressure filling and solidification, this process addresses the limitations of gravity casting, delivering dense, leak-proof, and high-strength components. The combination of empirical parameter settings, numerical simulation, and stringent operational controls ensures that shell castings meet the rigorous demands of modern engineering applications. As the industry evolves, low-pressure casting will continue to be a cornerstone for manufacturing premium shell castings, driving innovation in materials and design. My experience reaffirms that for critical Al-Si alloy components, low-pressure casting is not just an alternative but a necessity for achieving excellence in shell castings production.