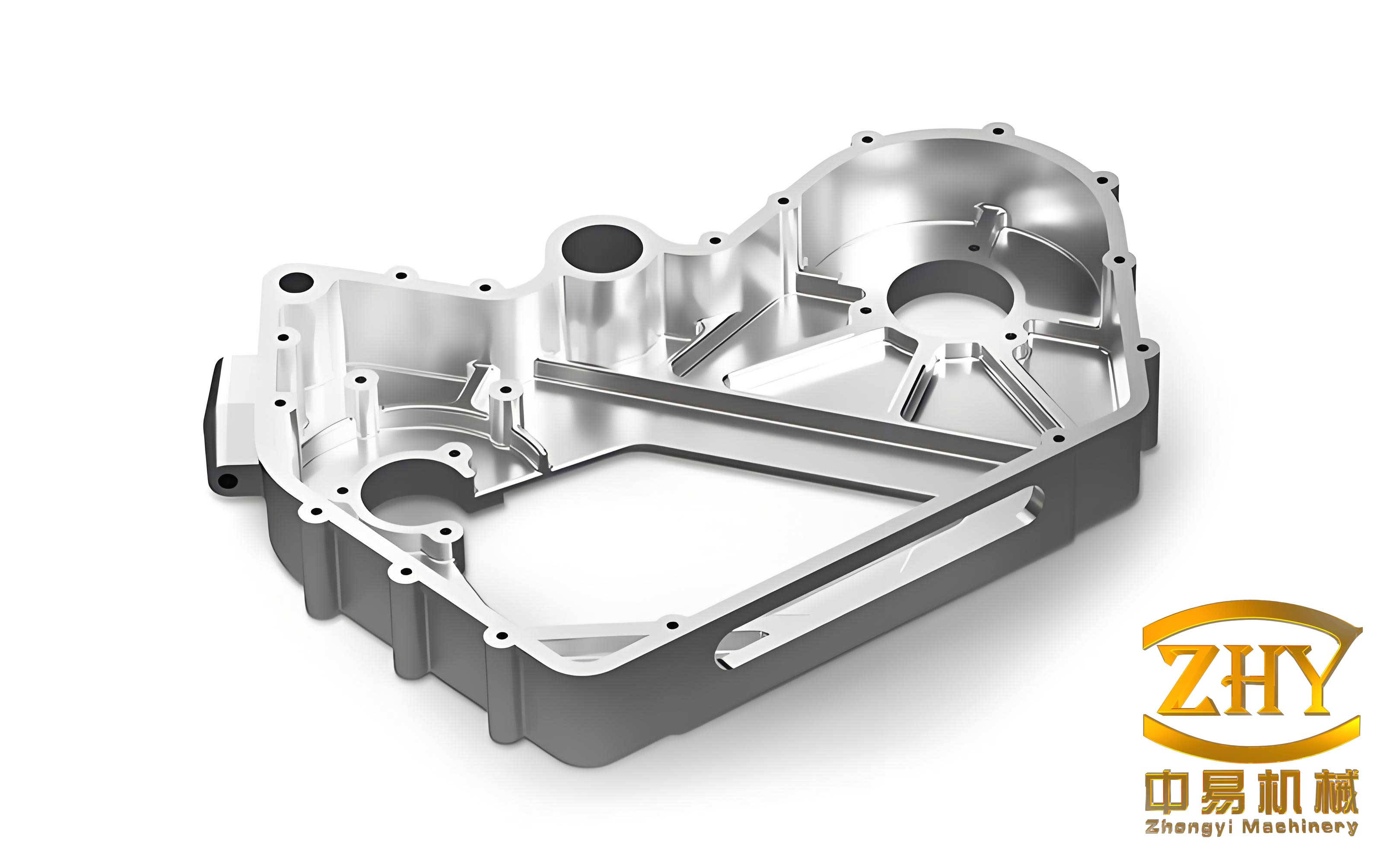

In my experience with foundry engineering, the design of casting processes for large, thin-walled shell castings made of aluminum alloy presents significant challenges, particularly in selecting appropriate casting shrinkage rates and managing deformation during casting and heat treatment. These shell castings, often used in automotive and aerospace applications, require precise dimensional control to ensure functionality and assembly. The choice of shrinkage rate is not uniform but must be tailored based on the geometry, structure, and wall thickness of the shell castings. Deformation, a common issue, can arise from both the casting solidification process and subsequent heat treatment, necessitating proactive measures to predict and mitigate it. This article delves into these aspects, drawing from practical trials and research, with a focus on methodologies for optimizing shrinkage selection and preventing deformation in shell castings. I will also discuss innovations in gating system design, such as serpentine sprue and high-pressure head pouring cups, which enhance filling characteristics for large shell castings.

The fundamental issue with shell castings lies in their expansive surface areas and varying wall thicknesses, which lead to non-uniform cooling and contraction. For instance, in a typical large shell casting like an oil pan or housing, the length can exceed 2000 mm, with an average wall thickness of 12 mm and variations up to 70 mm. This complexity demands a nuanced approach to shrinkage compensation. During initial trials, I observed that using a uniform shrinkage rate of 1% in all directions resulted in dimensional deviations: the length was shorter than calculated, the width was slightly larger, and the height matched expectations. This indicated that the actual shrinkage behavior differed by direction due to constraints from cores and mold geometry. Thus, for shell castings, it is crucial to analyze the casting structure thoroughly and assign differential shrinkage rates along the length, width, and height axes.

To quantify shrinkage rates, I often employ empirical formulas based on the material properties and casting geometry. For aluminum alloys like ZL104, the linear shrinkage can be approximated using the following relation, which accounts for thermal contraction during solidification and cooling: $$ \alpha = \frac{\Delta L}{L_0} = k \cdot \beta \cdot (T_{\text{pour}} – T_{\text{room}}) $$ where $\alpha$ is the shrinkage factor, $\Delta L$ is the length change, $L_0$ is the initial length, $k$ is a material constant (approximately 0.000022 °C⁻¹ for aluminum alloys), $\beta$ is a geometric constraint factor (ranging from 0.8 to 1.2 for shell castings), and $T_{\text{pour}}$ and $T_{\text{room}}$ are the pouring and room temperatures, respectively. In practice, I adjust $\beta$ based on the direction: for length, where contraction is less constrained, $\beta$ might be 1.1; for width, where cores restrict movement, $\beta$ could be 0.9; and for height, often free, $\beta$ is 1.0. This differential approach ensures that the mold dimensions compensate accurately for the actual shrinkage of shell castings.

I have summarized the typical shrinkage rate selections for large aluminum alloy shell castings in Table 1, which incorporates data from various projects. This table highlights how factors like wall thickness variation and core constraints influence the choice.

| Direction | Shrinkage Rate (%) | Key Influencing Factors | Typical Range for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 1.2 – 1.5 | Free contraction towards center, long span | Higher due to thermal gradient |

| Width | 0.8 – 1.0 | Core hindrance, flange areas | Lower due to restraint |

| Height | 1.0 – 1.2 | Minimal restraint, vertical freedom | Moderate,接近 free收缩 |

Another critical aspect is the direction of shrinkage. For shell castings exceeding 2000 mm in length, I found that shrinkage does not simply occur from one end to another; instead, it tends to contract inward from both ends toward the center. This is due to the temperature distribution during cooling, where the ends solidify first and pull the center. To address this, in mold design, I set the midpoint as the datum and apply increasing shrinkage rates outward. This method reduces length deviations to within 2 mm, as verified through coordinate measuring machines. The formula for adjusted length dimension $L_{\text{mold}}$ can be expressed as: $$ L_{\text{mold}} = L_{\text{casting}} \cdot (1 + s(x)) $$ where $s(x)$ is a position-dependent shrinkage function, e.g., $s(x) = s_0 + c \cdot |x – x_{\text{center}}|$, with $s_0$ as the base shrinkage and $c$ as a gradient coefficient. For shell castings, $c$ is typically 0.0005 per mm from the center.

Deformation in shell castings is another pervasive challenge. During casting, deformation manifests as warping or twisting, often at locations with thick sections or abrupt changes in geometry. For example, in a shell casting with flanges and pockets, areas near thick bosses or mounting pads are prone to distortion due to differential solidification rates. The deformation $\delta$ can be estimated using a simplified beam theory model: $$ \delta = \frac{F \cdot L^3}{3 E \cdot I} $$ where $F$ is the thermal stress force, $L$ is the characteristic length, $E$ is the elastic modulus of the alloy (≈70 GPa for aluminum), and $I$ is the moment of inertia of the cross-section. In shell castings, $F$ arises from constraints during cooling, calculated as $F = A \cdot \sigma_{\text{thermal}}$, with $\sigma_{\text{thermal}} = E \cdot \alpha \cdot \Delta T$, where $\Delta T$ is the temperature difference across the wall.

To proactively prevent casting deformation, I employ several strategies. First, I add pre-distortion to the mold based on predicted deformation patterns. If the shell casting tends to bend outward by 8 mm, the mold is offset inward by a similar amount. Second, I incorporate process ribs or gussets at critical locations, such as ends or corners. These ribs, designed with thicknesses matching the adjacent wall (e.g., 12 mm), provide restraint during solidification. They act as tensile members if the casting warps outward or compressive supports if it warps inward. The effectiveness hinges on simultaneous solidification, which I ensure by adjusting rib geometry using Chvorinov’s rule: $$ t_s = k \cdot \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^2 $$ where $t_s$ is solidification time, $V$ is volume, $A$ is surface area, and $k$ is a constant. For ribs in shell castings, I design them so that $(V/A)_{\text{rib}} \approx (V/A)_{\text{wall}}$, promoting concurrent solidification and avoiding hot tearing.

Heat treatment introduces additional deformation risks for shell castings due to residual stress relief and thermal expansion. When heating to solution treatment temperatures (e.g., 500°C for aluminum alloys), distorted areas may exacerbate. To counteract this, I use supports and clamping devices during heat treatment. For instance, I place steel braces under the flanges of shell castings and apply反向 bolts to impose corrective forces. The amount of force required can be derived from: $$ F_{\text{correct}} = \frac{E \cdot I \cdot \delta_{\text{target}}}{L^3} $$ where $\delta_{\text{target}}$ is the desired straightening displacement. This approach, combined with slow heating and cooling rates, minimizes热处理变形 in shell castings.

Table 2 summarizes common deformation types, causes, and preventive measures for large aluminum alloy shell castings, based on my observations across multiple projects.

| Deformation Type | Typical Location in Shell Castings | Primary Causes | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warping (bending) | Ends, flange edges | Non-uniform cooling, thick-thin transitions | Pre-distortion in mold, process ribs, controlled cooling |

| Twisting | Asymmetric sections, off-center cores | Uneven thermal stresses, mold restraint | Balanced gating, symmetric core design, stress relief annealing |

| Local buckling | Thin walls near thick bosses | High compressive stresses during solidification | Increase local stiffness, add ribs, optimize wall thickness ratio |

| Overall shrinkage distortion | Entire casting, especially length | Incorrect shrinkage rate, poor datum selection | Differential shrinkage rates, center-based datum, simulation验证 |

The gating system design plays a pivotal role in achieving sound shell castings. Initially, I used a single sprue at one end, but this led to slow filling at the far end, causing cold shuts and oxide inclusions. To improve this, I switched to a two-sprue system with侧浇注, which enhanced filling speed and reduced defects. However, the high drop height (up to 800 mm including risers) caused turbulence and dross formation. To mitigate this, I adopted a serpentine sprue design. The serpentine sprue, with its S-shaped path, reduces the velocity of the metal stream by dissipating kinetic energy through multiple bends. The pressure drop $\Delta P$ across a serpentine sprue can be approximated using the Darcy-Weisbach equation: $$ \Delta P = f \cdot \frac{L}{D} \cdot \frac{\rho v^2}{2} $$ where $f$ is the friction factor, $L$ is the effective length, $D$ is the diameter, $\rho$ is the density of aluminum alloy (≈2700 kg/m³), and $v$ is the flow velocity. For shell castings, I design the sprue with a diameter gradient to maintain laminar flow, targeting a Reynolds number below 2000 to minimize turbulence.

Furthermore, to ensure rapid and平稳充型 without increasing metal volume or sprue height, I implemented a high-pressure head pouring cup. This cup maintains a constant metallostatic pressure during pouring, compensating for the decreasing head as the mold fills. The pressure $P$ at the base of the pouring cup is given by: $$ P = \rho g h_{\text{effective}} $$ where $g$ is gravity (9.81 m/s²), and $h_{\text{effective}}$ is the dynamic head adjusted by the cup design. For shell castings, I use cups with baffles or chambers that sustain $h_{\text{effective}}$ at around 300-400 mm, enabling fast filling rates of 0.5-1.0 kg/s. This is critical for thin-walled shell castings to avoid mistruns and cold laps.

In a specific case study involving a large shell casting similar to an oil pan, I applied these principles. The shell casting measured approximately 2042 mm in length, 480 mm in width, and 649 mm in height, with an average wall thickness of 12 mm. The material was ZL104 aluminum alloy, and the process used resin sand cores with gravity pouring. Initially, deformation reached 7-8 mm at the ends due to thick sections (up to 70 mm) and poor shrinkage compensation. By revising the shrinkage rates to 1.3% in length, 0.9% in width, and 1.1% in height, and adding pre-distortion and process ribs, deformation was reduced to under 2 mm. The gating system was optimized with a serpentine sprue and high-pressure head cup, resulting in a fill time of about 30 seconds and minimal defects. This case underscores the importance of tailored approaches for shell castings.

To generalize, I have developed a formula for estimating the overall shrinkage compensation factor $C_{\text{total}}$ for shell castings, incorporating multiple variables: $$ C_{\text{total}} = \alpha_{\text{material}} \cdot \left(1 + \gamma_{\text{geometry}} + \gamma_{\text{restraint}}\right) $$ where $\alpha_{\text{material}}$ is the base shrinkage for the alloy (e.g., 1.2% for ZL104), $\gamma_{\text{geometry}}$ is a correction factor for aspect ratio (e.g., 0.1 for length/width >4), and $\gamma_{\text{restraint}}$ accounts for core hindrance (e.g., -0.2 for high restraint). For complex shell castings, I use casting simulation software to validate these factors, but empirical adjustments remain valuable.

Another key consideration is the interaction between shrinkage and residual stresses in shell castings. Residual stresses $\sigma_{\text{res}}$ can be estimated using: $$ \sigma_{\text{res}} = E \cdot \epsilon_{\text{shrink}} \cdot \left(1 – \frac{T_{\text{solidus}} – T_{\text{eject}}}{T_{\text{pour}} – T_{\text{room}}}\right) $$ where $\epsilon_{\text{shrink}}$ is the strain from shrinkage mismatch, and $T_{\text{solidus}}$ and $T_{\text{eject}}$ are the solidus and ejection temperatures. High residual stresses exacerbate deformation during heat treatment, so I often incorporate stress-relief steps in the process cycle for shell castings.

In terms of mold design for shell castings, I emphasize the use of metal molds for production runs due to their durability and consistent shrinkage behavior. The mold material (e.g., cast iron) has a different thermal expansion coefficient than aluminum, which I compensate by adjusting the shrinkage rates further. For instance, the effective shrinkage $s_{\text{eff}}$ for a metal mold can be expressed as: $$ s_{\text{eff}} = s_{\text{casting}} – \left( \alpha_{\text{mold}} – \alpha_{\text{casting}} \right) \cdot \Delta T_{\text{mold}} $$ where $\alpha_{\text{mold}}$ and $\alpha_{\text{casting}}$ are the thermal expansion coefficients of the mold and casting materials, and $\Delta T_{\text{mold}}$ is the mold temperature rise during pouring. This level of detail is crucial for high-precision shell castings.

Furthermore, the arrangement of cores in shell castings significantly impacts distortion. I design core assemblies to minimize restraint by using collapsible cores or adding clearance in critical areas. The force exerted by a core on the contracting casting can be modeled as: $$ F_{\text{core}} = A_{\text{contact}} \cdot E_{\text{core}} \cdot \epsilon_{\text{shrink}} $$ where $A_{\text{contact}}$ is the contact area, and $E_{\text{core}}$ is the elastic modulus of the core material (e.g., resin sand). By reducing $A_{\text{contact}}$ through strategic core partitioning, I lower the risk of deformation in shell castings.

Table 3 provides a comparison of gating system designs for large aluminum alloy shell castings, highlighting the benefits of serpentine sprues and high-pressure head cups.

| Gating Design | Fill Time (s) | Turbulence Level | Defect Rate (%) | Suitability for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single straight sprue | 60-90 | High | 15-20 | Poor, due to slow fill and dross |

| Multiple straight sprues | 40-60 | Medium | 10-15 | Moderate, better for symmetric castings |

| Serpentine sprue with high-pressure cup | 25-40 | Low | 5-10 | Excellent, fast and平稳充型 |

In conclusion, the successful production of large aluminum alloy shell castings hinges on a holistic approach to process design. Key takeaways include the necessity of differential shrinkage rates based on directional constraints, proactive deformation prediction through pre-distortion and ribs, and optimized gating for rapid, tranquil filling. The integration of serpentine sprues and high-pressure head pouring cups has proven particularly effective for shell castings, reducing defects and improving dimensional accuracy. Continuous refinement through simulation and empirical data is essential, as each shell casting presents unique challenges. By adhering to these principles, foundries can achieve high-quality shell castings that meet stringent industrial standards, paving the way for advancements in lightweight and complex component manufacturing.

To further elaborate, I often use statistical process control (SPC) to monitor shrinkage and deformation trends in shell castings. For example, I track the dimensional deviations of critical features over production runs and adjust shrinkage factors using regression models. A simple linear model for length deviation $\Delta L$ might be: $$ \Delta L = a \cdot s_{\text{set}} + b \cdot t_{\text{wall}} + c $$ where $s_{\text{set}}$ is the set shrinkage rate, $t_{\text{wall}}$ is the local wall thickness, and $a, b, c$ are coefficients determined from historical data of shell castings. This data-driven approach enhances consistency.

Additionally, the role of alloy composition cannot be overlooked for shell castings. Aluminum alloys like ZL104 have specific solidification ranges that affect shrinkage. The eutectic fraction influences the mushy zone behavior, which I account for in shrinkage calculations using: $$ s_{\text{effective}} = s_{\text{liquid}} + f_{\text{eutectic}} \cdot s_{\text{eutectic}} $$ where $s_{\text{liquid}}$ is shrinkage during liquid cooling, $f_{\text{eutectic}}$ is the eutectic fraction, and $s_{\text{eutectic}}$ is shrinkage during eutectic transformation. For shell castings with thin walls, this refinement helps in predicting micro-shrinkage porosity as well.

Ultimately, the design of casting processes for shell castings is an iterative endeavor that blends science and artistry. By sharing these insights, I aim to contribute to the broader foundry community’s ability to tackle the complexities of large, thin-walled aluminum alloy components. The journey from initial trial to production-ready shell castings is fraught with challenges, but with meticulous attention to shrinkage, deformation, and gating, success is attainable.