In my extensive experience within high-volume foundry production, addressing defect formation is a continuous engineering challenge. Among the most persistent and detrimental issues is the occurrence of porosity in casting. This defect category not only compromises the structural integrity of a component but is particularly critical for parts demanding high pressure-tightness, such as engine cylinder blocks and heads. The battle against porosity in casting is multifaceted, requiring a deep understanding of metallurgy, fluid dynamics, and sand mold behavior. The specific case of a compact, thin-walled cylinder block, weighing approximately 30kg, serves as an excellent paradigm for exploring the root causes and implementing effective countermeasures for porosity in casting.

The cylinder block is a quintessential high-integrity casting. It must exhibit superior density and be entirely free from leaks in both water and oil galleries, as verified by rigorous pressure testing. The presence of shrinkage, sand inclusions, or gas holes—collectively often manifesting as detrimental porosity—is unacceptable. The complexity arises from its geometric design: thin walls, numerous cored passages for coolant and lubricant, and critical bearing journals. When produced via green sand molding with resin-coated sand cores, the system becomes a significant generator of gaseous products during the pour. The core assembly, especially the intricate water jacket and oil gallery cores made from high-strength shell sand, represents a massive, concentrated source of gas evolution. This scenario creates a perfect storm for the formation of porosity in casting.

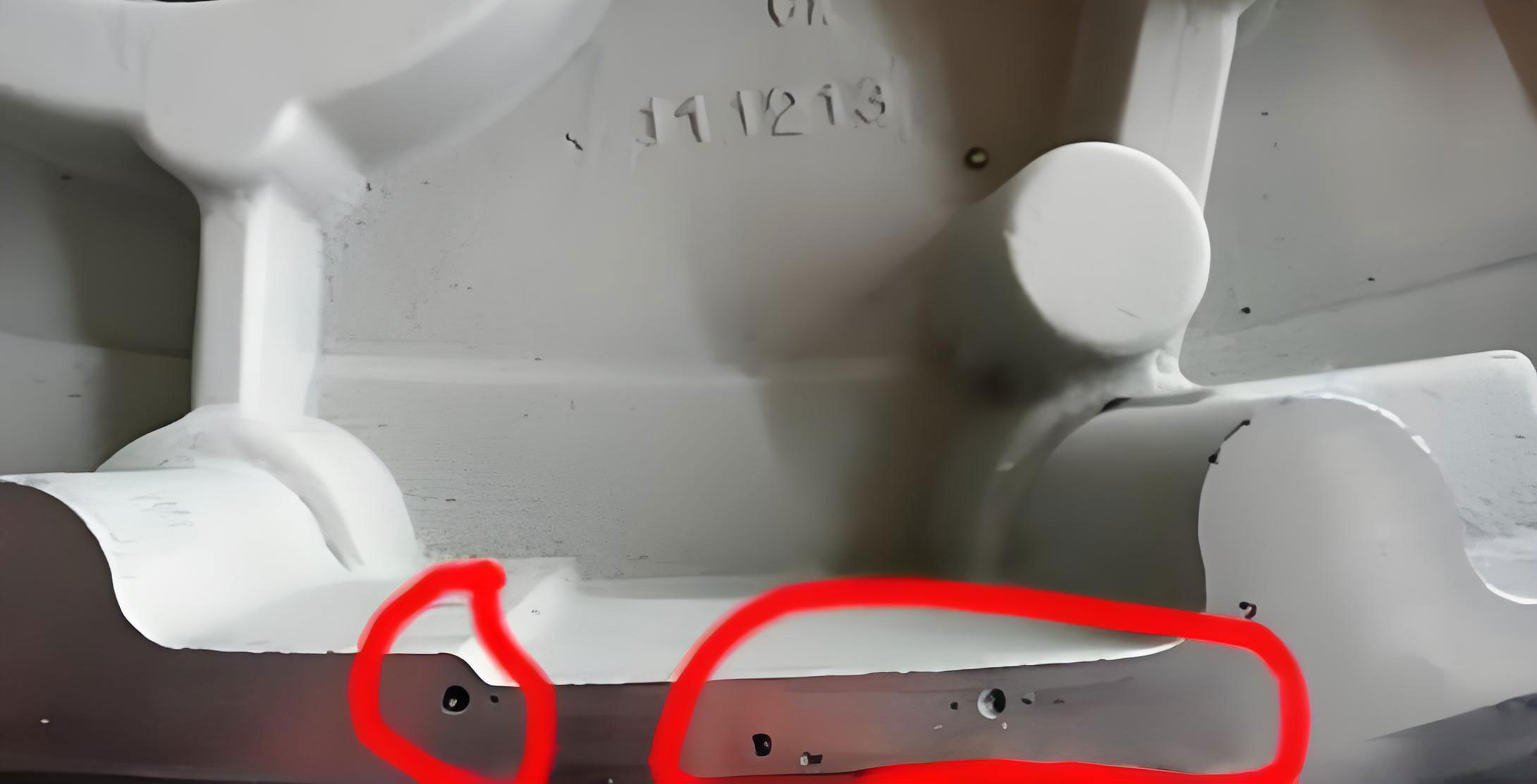

The manifestation of porosity in casting defects in our initial process was systematic. Gas holes, often irregular and 3-8mm in diameter, appeared predictably on the top deck surface, on raised bosses at the front and rear faces, and within the cylinder bores. Some cavities contained entrapped slag, indicating a combined gas-and-slag etiology. A root-cause analysis traced the sources of gas contributing to this porosity in casting:

- Mold Gas: Moisture from the green sand molding process vaporizes upon contact with molten metal.

- Core Gas: The extensive core package, particularly thin-section shell sand cores with high binder content, undergoes pyrolysis, releasing large volumes of gas.

- Coating Gas: The alcohol-based (醇基) refractory coating used on cores volatilizes rapidly, adding to the gas burden.

- Entrapped Air & Reaction Gas: Turbulent filling can trap air in the mold cavity. Furthermore, dissolved gases in the melt (like hydrogen, nitrogen) can precipitate during solidification. A critical reaction is the carbon-oxygen reaction occurring in stagnant, cooling metal: FeO + C → Fe + CO↑. If the CO bubbles cannot float out before the metal skin solidifies, they become trapped as another form of porosity in casting.

The original gating design, a middle-height vertical ingate system, exacerbated the problem. It caused significant turbulence, hindering the orderly escape of gases and leading to air entrainment. Furthermore, the long flow path to the top deck resulted in excessive temperature loss in the metal arriving last, reducing its ability to feed and allowing bubbles to be trapped more easily. While auxiliary vent pins and elevated pouring temperatures were tried, they proved insufficient to eliminate the porosity in casting. A systematic, multi-pronged strategy was required.

The fundamental equation governing the potential for gas defect formation can be conceptually framed by considering the gas pressure balance at the liquid metal front. A bubble will form or be trapped if the local gas pressure exceeds the opposing metallostatic and atmospheric pressures. We can express a simplified condition for the formation of porosity in casting as:

$$P_{gas} = P_{mold} + P_{core} + P_{coating} + P_{react} + P_{dissolved} > P_{hydrostatic} + P_{atm} + \frac{2\gamma}{r}$$

Where:

- $P_{gas}$ = Total gas pressure attempting to form a pore.

- $P_{mold}, P_{core}, P_{coating}$ = Partial pressures from mold moisture, core binder pyrolysis, and coating volatiles.

- $P_{react}$ = Pressure from in-situ reactions (e.g., CO formation).

- $P_{dissolved}$ = Pressure from gases precipitating from the melt.

- $P_{hydrostatic}$ = Metallostatic pressure head at that location in the mold.

- $P_{atm}$ = Atmospheric pressure.

- $\frac{2\gamma}{r}$ = Capillary pressure resisting bubble formation ($\gamma$ is surface tension, $r$ is pore radius).

Our goal is to minimize the left side of the inequality and maximize the right side, or, more practically, to provide easy escape paths for gases before they can form damaging porosity in casting.

A Systematic Approach to Mitigating Porosity

The campaign against porosity in casting involved three interconnected modifications: redesigning the filling system, implementing strategic overflows, and selecting a superior core coating.

1. Transition to a Bottom Gating System

The shift from a middle-ingate to a bottom-gating system was the most impactful change. The initial “step gating” hybrid was an improvement but retained some turbulence. The final pure bottom-gating design with six strategically sized ingates fundamentally altered the filling dynamics. This promotes laminar or quasi-laminar flow, minimizing air entrainment and allowing gases to rise counter-current to the incoming metal, venting through the top of the mold. The fluid flow can be described by modifying the Bernoulli equation for a real fluid, highlighting the importance of minimizing velocity-induced turbulence:

$$P_1 + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_1^2 + \rho g h_1 = P_2 + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_2^2 + \rho g h_2 + \Delta P_{loss}$$

Where $\Delta P_{loss}$ represents the energy loss due to friction and turbulence. Bottom gating, by maintaining a lower upward metal velocity ($v_2$) for a given flow rate compared to an impinging middle gate, significantly reduces $\Delta P_{loss}$ associated with turbulent dissipation, thereby creating a calmer fill that is less prone to generating and entrapping gases that lead to porosity in casting.

The table below summarizes the evolution and impact of the gating design changes on key parameters influencing porosity in casting:

| Gating Design | Filling Characteristic | Gas Escape Path | Thermal Gradient | Impact on Porosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Middle Gate | Highly turbulent, splashing | Obstructed, chaotic | Steep, hot spots at impingement | Severe porosity in top deck & bosses |

| Hybrid Step Gate | Moderately turbulent | Partially improved | More uniform but still skewed | Reduced, but not eliminated |

| Final Bottom Gate (6 ingates) | Laminar, smooth upward fill | Clear, counter-current flow | Favorable gradient (hot top) | Dramatic reduction in porosity |

2. Implementation of Pressed-Bead Overflow Risers

Recognizing that gas generation from sand and cores is inevitable, providing dedicated, high-efficiency escape routes is crucial. Pressed-bead overflow risers were added at the top deck and end bosses—the locations farthest from the ingates and traditional hot spots for porosity in casting. These are not feeding risers in the classical sense but are designed for gas and cold metal evacuation. The thin “bead” or press (1.8-2.2mm) acts as a thermal choke, ensuring the overflow connection freezes quickly after the mold is full, preventing reverse suction. The primary functions are:

- Gas Venting: Provides a direct, low-resistance path for gases accumulating at the mold ceiling to escape.

- Cold Metal & Slag Collection: The first, coolest, and often most oxidized metal to enter the cavity is diverted into the overflow, carrying with it non-metallic inclusions that could otherwise form slag-related porosity in casting.

- Temperature Modulation: By drawing off cooler metal, it helps maintain a hotter temperature gradient in the casting itself, slightly improving feedability and gas solubility.

The effectiveness of an overflow in removing gas-saturated metal can be rationalized by considering the solidification sequence. The overflow, having a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, solidifies first. The criterion for it to function is that its solidification time ($t_{overflow}$) is less than the solidification time of the critical section it protects ($t_{casting}$). Using Chvorinov’s Rule:

$$t = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n$$

Where $t$ is solidification time, $V$ is volume, $A$ is surface area, $B$ is the mold constant, and $n$ is an exponent (~2 for sand molds). By designing the overflow with a very low $V/A$ ratio (thin bead, tall shape), we ensure $t_{overflow} << t_{casting}$, guaranteeing it freezes early and traps the problematic first-fill metal, thereby preventing its defects from being retained in the main casting and reducing overall porosity in casting.

3. Selection of a Low-Gas, High-Adhesion Water-Based Coating

The final piece of the puzzle addressed a direct source of gas: the core coating. Replacing the volatile alcohol-based coating with an advanced water-based formulation had a direct and measurable impact on reducing one source of porosity in casting. The key performance differentiators are summarized below:

| Coating Property | Alcohol-Based Coating | Water-Based Coating | Benefit for Porosity Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Generation | Very High (rapid alcohol combustion) | Low (water vapor + binder pyrolysis) | Directly reduces $P_{coating}$ term in gas pressure equation. |

| Suspension Stability | Poor, prone to settling | Excellent with proper additives | Ensures uniform coating thickness; prevents localized weak spots that cause sand erosion and subsequent sand-related defects. |

| Adhesion/Peel Resistance | Moderate | Superior when properly dried | Prevents coating flaking during mold assembly or metal pour, eliminating a source of inclusions that can nucleate porosity in casting. |

| Application Control | Fast drying, hard to correct | Slower drying, allows for adjustment | Enables consistent, controlled application to achieve optimal insulating layer without excess. |

The gas evolution volume ($V_{gas}$) from a coating can be approximated as a function of temperature and coating mass. For a water-based coating, the primary gas is steam, released over a temperature range as water evaporates and then chemically bound water is released from clay minerals. For an alcohol-based coating, the release is a more violent, rapid combustion. The total gas contributing to potential porosity in casting is lower and more controlled with the water-based system. The drying process is critical and must be complete to avoid steam explosions; a well-controlled drying oven cycle is essential.

Integrated Process Analysis and Quality Outcomes

The combined effect of these three measures created a synergistic defense against porosity in casting. The bottom-gating system ensures a calm fill. The overflows at the high points provide dedicated escape routes for both gas and contaminated metal. The low-gas coating removes a significant source of volatiles from the system. The result was a dramatic reduction in scrap rates due to gas holes and slag inclusions.

A quantitative framework for evaluating the success can be built around the concept of the Niyama Criterion, often used to predict shrinkage porosity but also indicative of conditions ripe for gas pore formation. The criterion states that porosity is likely where the thermal gradient $G$ divided by the square root of the cooling rate $\dot{T}$ falls below a critical value. While originally for shrinkage, a low $G/\sqrt{\dot{T}}$ ratio also indicates a region of long solidification time under a low gradient—precisely where gas bubbles have ample time to nucleate and grow rather than be forced out. Our modifications improved this ratio in critical areas:

$$Niyama = \frac{G}{\sqrt{\dot{T}}}$$

- Bottom Gating: Improved temperature uniformity, potentially altering $G$ favorably.

- Overflows: Drew off cooler metal, increasing the local $G$ in the adjacent casting region.

- Reduced Gas Pressure ($P_{gas}$): Even in areas with a marginally low Niyama value, a lower internal gas pressure decreases the probability that a pore will actually form and expand to a damaging size.

The primary metric for success was the drastic fall in leak-test failures during hydrostatic and pneumatic testing of the water and oil passages. This confirmed that the internal porosity in casting, which is most detrimental to functionality, had been effectively controlled.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

While the implemented solutions were highly effective, the fight against porosity in casting is never truly over. Further refinement is always possible. Modern tools like computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and solidification simulation allow for virtual prototyping of gating and venting designs. These simulations can model gas generation from sand and coatings, track the movement of entrapped air and oxides, and predict final defect locations with increasing accuracy. The governing equations solved in such software, like the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow and the Fourier equation for heat transfer, provide a deep digital insight:

$$\rho \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{v}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{v} \right) = -\nabla p + \mu \nabla^2 \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{F}$$

$$\rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{Q}$$

Where $\mathbf{v}$ is velocity, $p$ is pressure, $\mu$ is viscosity, $T$ is temperature, $k$ is thermal conductivity, and $\dot{Q}$ includes latent heat release. Coupling these with a gas evolution/pore nucleation model is the frontier for predicting porosity in casting.

Other advanced strategies could include:

- Inert or Reduced-Pressure Pouring: To minimize air entrainment and oxide formation.

- Vacuum-Assisted Venting: Actively drawing gases out of the mold cavity during pouring.

- Optimized Binder Chemistry: Using core binders designed for lower gas evolution or specific gas release profiles (e.g., early vs. late release).

- Real-Time Process Monitoring: Using thermal imaging to track fill patterns and solidification fronts to identify areas at risk for porosity in casting.

In conclusion, the successful reduction of porosity in casting, as exemplified by the cylinder block project, is not achieved by a single silver bullet but through a holistic system analysis. It requires attacking the problem from multiple angles: controlling fluid flow to minimize turbulence and air entrainment, designing effective venting pathways to evacuate generated and entrapped gases, and selecting process materials that inherently lower the gas load. The transition to a bottom-gating system, the implementation of pressed-bead overflow risers, and the adoption of a high-performance water-based core coating represent a powerful, synergistic trilogy of solutions. This integrated approach systematically lowers the total gas pressure ($P_{gas}$) within the mold while improving the conditions for its escape, thereby dramatically suppressing the formation of costly and performance-limiting porosity in casting. This methodology provides a robust framework that can be adapted and applied to a wide range of complex, high-integrity castings where internal soundness is paramount.