In the realm of industrial casting, porosity in casting remains a pervasive and costly defect, particularly for complex components such as compressor cylinder blocks. As a practitioner in a foundry specializing in heavy-duty castings, I have extensively investigated the root causes and solutions for porosity in casting, focusing on large piston-type compressor cylinder bodies. These castings, made of HT300 gray iron, exhibit intricate geometries with internal water and air passages, leading to significant challenges in controlling porosity in casting. This article delves into a first-person account of the analysis, simulation, and practical measures implemented to address these defects, emphasizing the multifaceted approach required to minimize porosity in casting.

The cylinder block casting in question features an outer contour of approximately 1320 mm × 1160 mm, with a cylinder bore diameter of 810 mm and an average wall thickness of 45 mm, varying from less than 35 mm to over 80 mm. Its complex structure includes core assemblies for air and water channels, creating a spatially networked internal system. The casting must adhere to stringent standards, requiring pressure tightness and freedom from defects like cracks, cold shuts, and especially porosity in casting. Historically, with increased production rates, the scrap rate for such large cylinders reached around 20%, primarily due to porosity clusters in critical areas such as the bore and cylinder shoulders, leading to leaks during pressure testing. This prompted a thorough review of our processes to combat porosity in casting.

Our production environment utilizes resin-bonded sand for both molds and cores, with a molding box size of 1700 mm × 1700 mm. The gating system was originally a bottom-pour design with a 80 mm diameter sprue, ring-shaped runners, and multiple ingates. However, this setup often exacerbated porosity in casting due to inadequate venting and gas entrapment. To systematically tackle porosity in casting, we analyzed factors across materials, molding, design, and melting, supported by CAE simulations. Below, I detail each aspect, incorporating tables and formulas to summarize key insights.

Current Production Status and Defect Manifestation

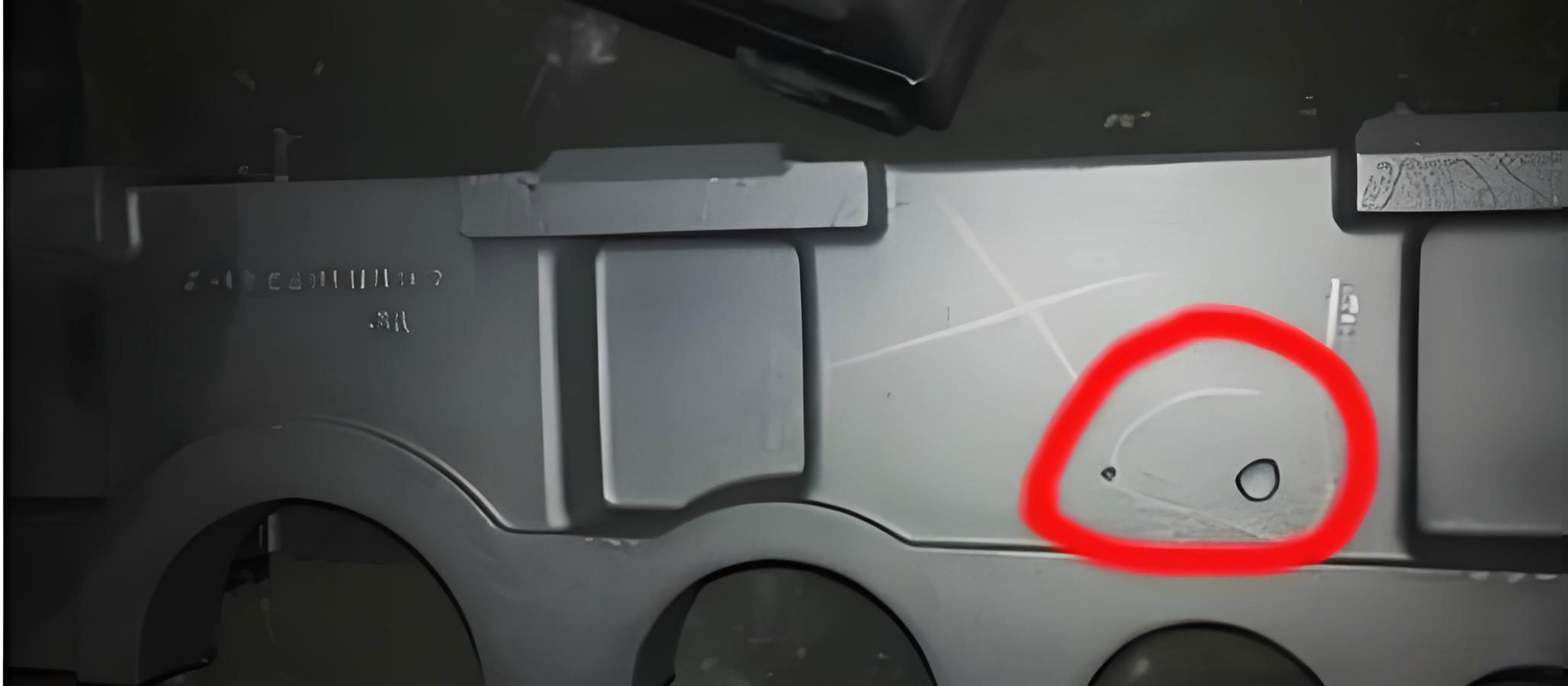

Porosity in casting typically appeared as localized clusters of 1–2 gas holes in the cylinder bore after rough machining or as visible groups in the cylinder shoulder after cleaning. These defects directly impacted the pressure integrity, causing failures during hydrostatic and pneumatic tests at 0.6 MPa and 0.2 MPa, respectively. The accelerated production pace heightened the incidence of porosity in casting, necessitating a holistic investigation. Our initial assessment revealed that porosity in casting often correlated with regions of last solidification or high gas concentration, prompting a focus on gas generation and venting efficiency.

Causes and Solutions for Porosity in Casting

Porosity in casting arises from multiple interactive factors. We categorized these into molding materials, molding and core assembly, process design, and melting/pouring practices. Each category contributes to gas formation, entrapment, or inadequate removal, leading to porosity in casting.

1. Molding Materials: Gas Generation and Permeability

The quality of molding materials significantly influences porosity in casting. Excessive gas evolution from resins or high fines content can reduce permeability, trapping gas within the molten metal. We measured key parameters across four sand mixers to assess resin addition, gas evolution, and strength. The data, summarized in Table 1, indicated high loss on ignition (3%) and residual moisture, exacerbating porosity in casting.

| Mixer No. | Sand Output (mL) | Resin Addition (%) | Catalyst Addition (mL) | Catalyst/Resin Ratio (%) | 24h Tensile Strength (MPa) | Gas Evolution (mL/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 470 | 1.5 | 250 | 53.2 | 0.22 / 0.70 | 21.3 |

| 2 | 628 | 1.3 | 380 | 60.8 | 0.20 / 0.75 | 16.5 |

| 3 | 710 | 1.4 | 420 | 59.2 | 0.18 / 0.68 | 18.2 |

| 4 | 280 | 1.3 | 180 | 64.3 | 0.20 / 0.70 | 14.5 |

To mitigate porosity in casting, we reduced resin addition to below 1.1% for core lines and 1.3% for molding lines, decreasing gas evolution. We increased new sand proportion to 15% to lower fines content and implemented regular parameter checks. Additionally, when humidity exceeded 55%, we used kerosene torches to dry molds and cores, reducing residual moisture that contributes to porosity in casting. The gas evolution rate can be modeled by the Arrhenius equation for resin decomposition: $$ G = A \cdot e^{-E_a/(RT)} $$ where \( G \) is gas evolution rate, \( A \) is pre-exponential factor, \( E_a \) is activation energy, \( R \) is gas constant, and \( T \) is temperature. Lowering resin content reduces \( A \), directly curbing porosity in casting.

2. Molding and Core Assembly: Venting and Moisture Control

Imperfections in molding and core assembly, such as exposed core prints or blocked vents, hinder gas escape, promoting porosity in casting. We found instances of core prints being exposed due to inaccurate dimensions, and excessive use of sealing compounds that could intrude into cavities. Moreover, inadequate drying time before pouring allowed residual volatiles to generate gas. Our measures included repairing cores with refractory paste to prevent lateral gas leakage, ensuring vent passages are clear, and minimizing sealant use. We also extended drying times: for humidity below 45%, drying for 2 hours; above 45% (e.g., rainy seasons), at least 4 hours. This reduces water vapor pressure, which can be expressed as: $$ P_{H_2O} = P_0 \cdot e^{-\Delta H_v/(RT)} $$ where \( P_{H_2O} \) is vapor pressure, \( P_0 \) is constant, and \( \Delta H_v \) is enthalpy of vaporization. Longer drying lowers \( P_{H_2O} \), decreasing gas contribution to porosity in casting.

3. Process Design: Gating, Venting, and Solidification Control

Process design flaws, such as undersized vents or improper gating, are critical to porosity in casting. Initially, vent rods were 6 mm diameter, and the bottom-pour gating caused turbulent filling, trapping gas. We enlarged vent rods to 8 mm and used dual vents in core prints, increasing total vent area to 0.06% of core surface area. Risers were enlarged to 80/60 mm to enhance gas migration and feeding. The gating system was redesigned into a main-sub system: the main system became a closed bottom-pour, while a top-pour subsystem was added. This hybrid approach combines advantages of bottom, top, and step gating, improving metal feeding and gas expulsion to reduce porosity in casting. The pressure balance in vents can be described by: $$ \Delta P = \frac{8 \mu L Q}{\pi r^4} $$ where \( \Delta P \) is pressure drop, \( \mu \) is gas viscosity, \( L \) is vent length, \( Q \) is gas flow rate, and \( r \) is vent radius. Increasing \( r \) reduces \( \Delta P \), facilitating gas escape and minimizing porosity in casting. Additionally, we inserted chills in thick sections to promote directional solidification, reducing isolated pools where porosity in casting could form.

4. Melting and Pouring: Temperature and Gas Solubility

Melting and pouring parameters affect gas solubility and solidification kinetics, influencing porosity in casting. Low pouring temperatures increase viscosity, hindering gas bubble floatation, while high temperatures may exacerbate gas dissolution. Our practice involved melting in cupolas above 1460°C, with pouring at 1320–1340°C. To address porosity in casting, we adjusted to a higher pouring range of 1350–1360°C, ensuring adequate fluidity for gas escape while minimizing gas pickup. The solubility of hydrogen in iron, a common gas causing porosity in casting, follows Sieverts’ law: $$ [H] = K_H \cdot \sqrt{P_{H_2}} $$ where \( [H] \) is hydrogen concentration, \( K_H \) is equilibrium constant, and \( P_{H_2} \) is hydrogen partial pressure. Proper temperature control and slag removal reduce \( P_{H_2} \), lowering gas content and porosity in casting. We also implemented isothermal pouring to maintain consistent thermal gradients, reducing turbulence-induced gas entrapment that leads to porosity in casting.

CAE Simulation for Porosity in Casting Analysis

To validate our improvements, we employed casting simulation software (similar to Huazhu CAE) for solidification analysis. The software uses 3D modeling and finite element methods to predict shrinkage and gas entrapment. As shown in the simulation results, we visualized liquid fraction distribution over time, identifying regions prone to porosity in casting due to late solidification or gas trapping. The simulation confirmed that enlarging vents and adding chills reduced isolated liquid pockets, thereby mitigating porosity in casting. The solidification time \( t_s \) can be estimated using Chvorinov’s rule: $$ t_s = C \cdot \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^2 $$ where \( V \) is volume, \( A \) is surface area, and \( C \) is mold constant. By modifying geometry and cooling, we optimized \( t_s \) to ensure vents remain open longer, allowing gas escape before solidification seals porosity in casting. The simulation also highlighted the effectiveness of the hybrid gating system in reducing turbulent energy, which is correlated with gas entrainment. The turbulent kinetic energy \( k \) in fluid flow can be expressed as: $$ k = \frac{3}{2} (u’)^2 $$ where \( u’ \) is fluctuating velocity component. Lower \( k \) from improved gating decreases gas entrapment, directly reducing porosity in casting.

Integrated Measures and Results

Our comprehensive approach involved simultaneous actions across all process stages. Key outcomes included a significant reduction in scrap rates due to porosity in casting. We monitored parameters through regular audits, as summarized in Table 2, which tracks improvements in gas evolution and defect incidence.

| Parameter | Before Improvement | After Improvement | Impact on Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resin Addition (%) | 1.3–1.5 | 1.1–1.3 | Reduced gas evolution by ~15% |

| Vent Diameter (mm) | 6 | 8 | Improved gas flow rate by ~80% |

| Pouring Temperature (°C) | 1320–1340 | 1350–1360 | Enhanced bubble floatation |

| Drying Time (hours) | 1–2 | 2–4 | Lowered moisture content |

| Defect Rate (%) | ~20 | <5 | Significant reduction in porosity |

The hybrid gating system proved particularly effective, as it allowed controlled filling with minimal turbulence, while enlarged vents and risers facilitated gas escape. We also introduced statistical process control to monitor variables like sand moisture and temperature, using control charts to preempt issues related to porosity in casting. The defect reduction underscores the importance of a systems-thinking approach to porosity in casting, where each factor interplays to either exacerbate or alleviate the problem.

Conclusion

In summary, addressing porosity in casting requires a multifaceted strategy encompassing material selection, process design, and operational controls. Through detailed analysis, we identified that porosity in casting in large cylinder blocks stemmed from excessive gas generation, inadequate venting, and suboptimal solidification patterns. By reducing resin content, enhancing vent designs, implementing a hybrid gating system, and optimizing pouring temperatures, we nearly eliminated porosity in casting defects. The use of CAE simulations provided valuable insights for iterative improvements. This experience reinforces that porosity in casting is not an isolated issue but a systemic challenge demanding integrated solutions. Future work could explore advanced materials with lower gas evolution or real-time monitoring systems to further combat porosity in casting. Ultimately, proactive management of these factors ensures high-quality castings, reducing waste and enhancing productivity in foundry operations.