In my extensive experience within foundry engineering, addressing defects such as porosity in casting remains a paramount challenge, directly impacting the structural integrity and performance of high-value components. This article delves into a detailed first-person investigation and resolution of gas hole defects encountered in the production of a machine tool pillar casting, specifically focusing on the methodologies employed to analyze and eliminate porosity in casting through rigorous process analysis and advanced simulation techniques. The component under scrutiny was a grey iron HT300 casting, produced in a two-cavity mold with a total pouring weight of approximately 235 kg. The persistent appearance of porosity in casting—manifesting as blowholes on the upper flange face and shrinkage-like defects on the inner walls of the main shaft and flange holes—posed significant quality and cost concerns. My approach centered on dissecting the existing gating and venting system, leveraging computational modeling to visualize flow and solidification phenomena, and implementing targeted corrective actions. The core of this endeavor was to understand the root causes of porosity in casting and to establish a robust framework for its prevention, a theme that will be recurrently emphasized throughout this discussion.

The casting in question had overall dimensions of 620 mm × 393 mm × 427 mm, with a predominant wall thickness of 12 mm and critical sections like the Φ100 mm hole and flange areas being 25 mm and 30 mm thick, respectively. The molding process utilized furan resin sand, with strict controls on resin addition and sand regeneration. The core assembly comprised five sand cores, with intricate interconnections that, as initially designed, presented potential challenges for gas evacuation. The original gating system was a bottom-gating design with reverse rising channels, featuring a sprue of Φ60 mm, a runner of 45 mm × 55 mm, and four inner gates of Φ20 mm each. The pouring time was initially set at an empirically determined 10 seconds. The venting system included two small exothermic risers and two blind risers, with a calculated vent-to-ingate area ratio of only 0.38. It was this configuration that my analysis identified as a primary contributor to the formation of porosity in casting.

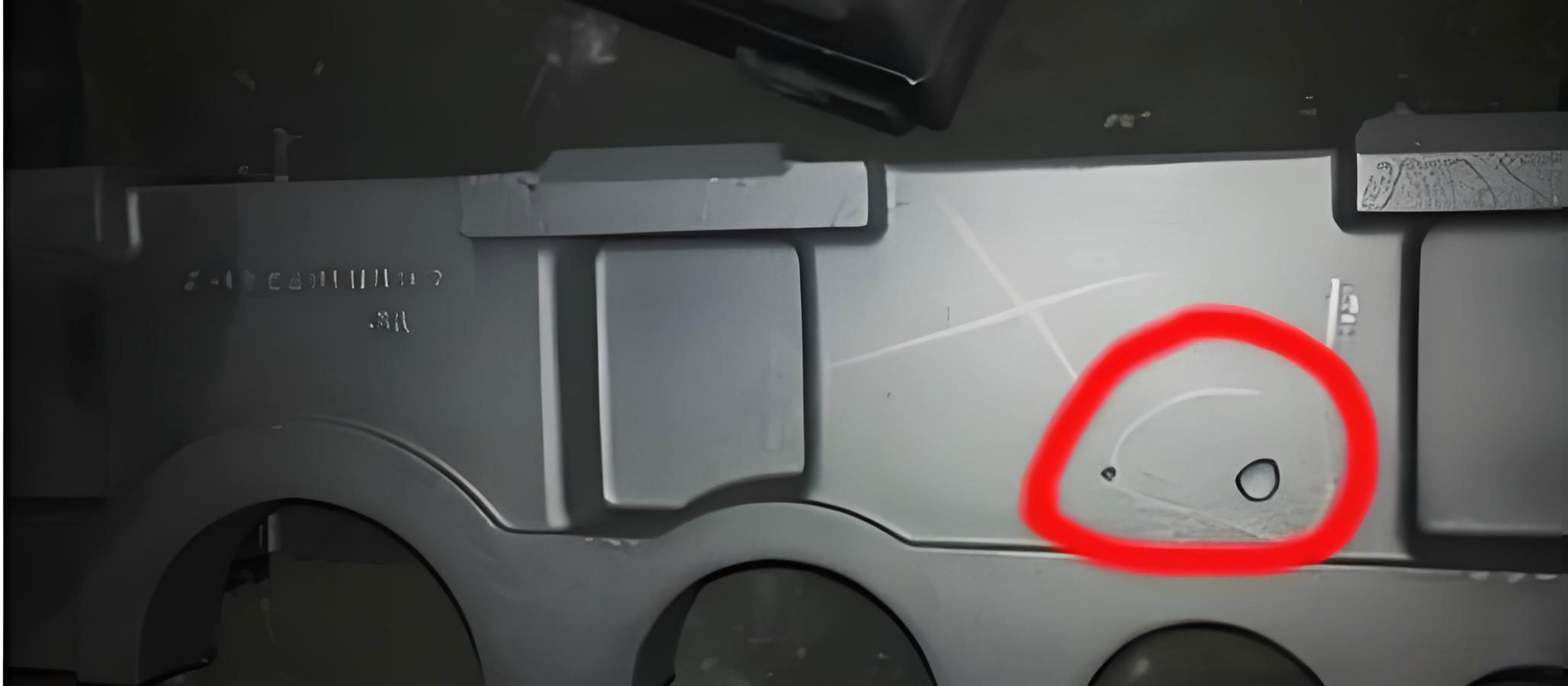

The first phase of my investigation involved a thorough cause-and-effect analysis. The defects were clearly identified: large, concentrated blowholes on the top flange surface (an ideal location for gas accumulation) and dispersed shrinkage-porosity on the inner walls of the machined holes. This pattern suggested the involvement of both侵入性气体 (entrapped gas) and micro-shrinkage mechanisms, both falling under the broad umbrella of porosity in casting. To quantify the process parameters, I began by recalculating the theoretical pouring time. For a casting of this weight and section thickness, a faster pour is generally desirable for thin sections to prevent mist runs, but it must be balanced against turbulent flow. Using established empirical formulas, I derived two estimates:

$$t = \sqrt{G} + \sqrt[3]{G} \quad \text{where } G = 235 \text{ kg}$$

$$t = \sqrt{235} + \sqrt[3]{235} \approx 15.33 + 6.17 = 21.5 \text{ seconds}$$

An alternative formula gave:

$$t = K \sqrt{G} \quad \text{with } K = 1.1$$

$$t = 1.1 \times \sqrt{235} \approx 1.1 \times 15.33 = 16.86 \text{ seconds}$$

Given the dominant 12 mm wall, a quicker pour was targeted. Therefore, a pouring time (t) of around 16 seconds was deemed more appropriate than the original 10 seconds. This adjustment was crucial because an excessively short pouring time necessitates a higher flow rate, which can lead to turbulent filling and air entrainment, a direct precursor to porosity in casting.

Next, I scrutinized the gating system design. The original area ratio of sprue : runner : ingate was 1 : 1.75 : 0.44. The total ingate area (∑A_ingate) was 12.57 cm². Using principles of fluid flow for pressurized systems (orifice outflow), I recalculated the required total ingate area for different pouring times. The governing equation for metal flow rate is:

$$Q = \mu \cdot A \cdot \sqrt{2 g h_p}$$

Where Q is the flow rate (kg/s), μ is the discharge coefficient, A is the choke area (cm²), g is gravity (981 cm/s²), and h_p is the metallostatic pressure head (cm). The total weight G = ρQ t, leading to the formula for total ingate area:

$$\sum A_{ingate} = \frac{G}{0.31 \cdot \mu_3 \cdot t \cdot \sqrt{h_p}}$$

Here, μ_3 represents the effective discharge coefficient for the entire system. For the original 10-second pour, this calculation yielded a required ∑A_ingate significantly larger than the 12.57 cm² used. Conversely, for a 16-second pour, the calculated area was more moderate. This confirmed that the original ingates were undersized, forcing a high exit velocity that promoted jetting and air entrainment. The venting system was equally problematic. The vent-to-ingate area ratio (∑A_vent / ∑A_ingate) is a critical metric for allowing core and mold gases to escape before the metal solidifies. A ratio of 0.38 is grossly inadequate; industry experience suggests a ratio of 1.0 to 1.5 or higher is necessary for resin sand molds to effectively prevent porosity in casting. The original vents were simply too small and too few.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of the original filling process vividly illustrated these issues. The simulation revealed that the metal jet from the bottom-up ingates reached velocities as high as 3.7 m/s upon exiting, vertically impacting the upper flange region within the first second. This created severe turbulence, oxide film formation, and gas entrapment. The metal front advanced in an unstable, sloped manner, further aggravating air entrainment. The vents filled last, confirming their ineffectiveness in evacuating the large volume of gas generated from the resin-bonded sand cores during the critical early stages of filling and initial solidification. This simulation data was instrumental in pinpointing the mechanisms of porosity in casting formation.

Based on this analysis, I formulated and evaluated two improved gating system designs, designated as Scheme 1 and Scheme 2. The primary objectives were to: 1) Increase the total ingate area to reduce flow velocity, 2) Increase the total vent area substantially, 3) Modify the ingate entry geometry to promote smoother, more horizontal filling, and 4) Ensure proper venting pathways from all core assemblies.

| Parameter | Original Design | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprue Diameter (mm) | Φ60 | Φ60 | Φ60 |

| Runner Cross-section (mm) | 45 × 55 | 45 × 55 | 45 × 55 |

| Ingate Type | Circular, bottom-up | Circular, bottom-up | Rectangular, horizontal entry |

| Number of Ingates | 4 | 4 | 4 (transitioned) |

| Ingate Dimensions | Φ20 mm | Φ25 mm | See Fig. 6 (Area ~6.8 cm² each) |

| Total ∑A_ingate (cm²) | 12.57 | 19.64 | ~27.2 |

| Sprue : Ingate Area Ratio | 1 : 0.44 | 1 : 0.69 | 1 : ~0.96 |

| Pouring Time Target (s) | 10 | 16 | 16 |

| Number of Vents | 2 (30×8 mm) | 6 (40×10 mm) | 6 (40×10 mm) |

| Total ∑A_vent (cm²) | 4.8 | 24.0 | 24.0 |

| Vent-to-Ingate Ratio (∑A_vent/∑A_ingate) | 0.38 | 1.22 | 0.88 |

Scheme 1 retained the circular, bottom-up ingates but increased their diameter to Φ25 mm, raising ∑A_ingate to 19.64 cm². Scheme 2 involved a more radical change: the ingates were transformed into a rectangular, horizontally-oriented entry system. This design aimed to diffuse the metal stream and introduce it more gently into the mold cavity. Applying the continuity equation (A₁v₁ = A₂v₂) to the Scheme 2 ingate transition, the exit velocity was theoretically reduced, aligning with simulation results showing a calmer fill. The venting system was overhauled in both schemes, with six flat vents (40 mm × 10 mm) installed, primarily on the top flange, boosting the vent-to-ingate ratio above 1.0 for Scheme 1, a critical step to combat porosity in casting.

The effectiveness of these modifications was validated through comprehensive solidification and thermal analysis simulation. Temperature profiles and cooling curves at key points, particularly at the defect-prone flange top and the Φ100 mm hole wall, were compared. A critical concept in analyzing gas defect formation is the “coexistence zone” or “danger period.” This is the time window during which the metal is within its solidification range (between liquidus and solidus temperatures) and the adjacent sand core is hot enough to rapidly decompose and produce gas. The duration of this coexistence zone is directly related to the risk of porosity in casting. The simulation provided quantitative data for this:

| Design Scheme | Core Gas Generation Start Time (s) | Metal Solidification Start (Liquidus) (s) | Metal Solidification End (Solidus) (s) | Coexistence Zone Duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | ~16 | ~16 | ~43 | ~27 |

| Scheme 1 (Φ25 bottom-up) | ~16 | ~16 | ~43 | ~27 |

| Scheme 2 (Horizontal entry) | ~29 | ~29 | ~38 | ~9 |

The data revealed a profound insight. While Scheme 1 improved flow characteristics, it did not significantly alter the thermal history at the metal-core interface in the upper regions compared to the original design. Scheme 2, with its horizontal filling pattern, fundamentally changed the thermal sequence. The metal reached the top flange later, but once it did, it cooled and solidified more rapidly. This drastically shortened the coexistence zone from 27 seconds to just 9 seconds, greatly reducing the opportunity for core gases to infiltrate the solidifying metal and cause porosity in casting. The simulation of filling patterns for Scheme 2 confirmed a much more quiescent, layer-by-layer fill without the violent impingement and sloshing observed in the original process.

Furthermore, the simulation allowed for an in-depth analysis of the shrinkage-porosity defect in the lower Φ100 mm hole. This defect, often intermixed with gas pores, is another facet of porosity in casting. Grey iron HT300 has a relatively wide solidification range due to its lower carbon equivalent, making it prone to interdendritic shrinkage. The simulation predicted areas of reduced density, corresponding to microporosity. The density (ρ) in these zones can be related to the solid fraction (f_s) and the porosity level. An approximate relationship can be derived from mass balance:

$$\rho_{casting} = \rho_{sound} \cdot (1 – \alpha)$$

where $\alpha$ is the volumetric fraction of porosity in casting. For HT300, the standard density ($\rho_{sound}$) is approximately 7.25 g/cm³. The simulation indicated localized densities as low as 7.1 g/cm³ in the shrinkage zone, implying a porosity level ($\alpha$) of about 2%. This was mapped against solidification sequences, showing that these areas were hot spots, inadequately fed due to the early formation of a rigid dendritic network in the surrounding thinner sections. While this level of porosity in casting might be acceptable if located within the machining allowance, the analysis underscored the importance of thermal management. Solutions such as localized chilling or repositioning the ingate to avoid creating such isolated hot spots were considered as further refinements to eradicate all forms of porosity in casting.

The integration of strict process control measures was also part of the holistic solution. I emphasized operations such as using molds and cores on the same day of production, controlled application of coatings (avoiding vent passages), ensuring all core vent channels are connected to the outside atmosphere, and preheating ladles. Maintaining a consistent pouring temperature and a controlled, steady pour within the 16-second window were imperative to stabilize the conditions that minimize porosity in casting.

In conclusion, this investigative journey from defect discovery to resolution powerfully demonstrates the systemic approach required to tackle porosity in casting. The key technical learnings are multifold: First, a scientifically determined pouring time is essential to balance fill speed against turbulence. Second, the gating system must be designed with adequate choke area to ensure calm, non-jetting metal entry; a sprue-to-ingate area ratio closer to 1:0.7 or higher proved beneficial. Third, venting is not an afterthought—the vent-to-ingate area ratio should decisively exceed 1.0 for resin sand molds to provide a low-resistance escape path for gases. Fourth, the geometry and orientation of the ingates profoundly influence the thermal profile during filling and initial solidification; a horizontal entry can significantly shorten the critical gas-metal coexistence period. Finally, modern casting simulation software is an indispensable tool for diagnosing the complex interplay of fluid flow, heat transfer, and solidification that leads to porosity in casting. It allows for virtual prototyping of solutions, saving considerable time and cost associated with physical trials. By adhering to these principles—meticulous design, quantified process windows, and predictive simulation—the pervasive challenge of porosity in casting can be effectively mitigated, leading to enhanced product quality, improved yield, and reduced manufacturing costs for critical cast components across industries.