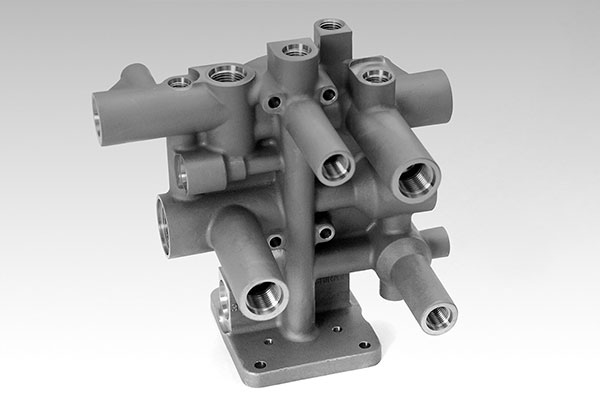

In the realm of advanced manufacturing, lost wax investment casting stands as a pivotal near-net-shape forming technique, renowned for its ability to produce complex components with minimal machining. This process, which involves creating expendable wax patterns, coating them with refractory materials, and pouring molten metal, is extensively utilized in aerospace, automotive, and other high-precision industries due to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness. However, the multi-step nature of lost wax investment casting introduces numerous variables that can lead to dimensional inaccuracies, such as those observed in flange castings. In this article, I will delve into a detailed investigation of dimensional deviations in flange components produced through lost wax investment casting, employing fault tree analysis and fishbone diagram methodologies to identify root causes, with a particular focus on the influence of wax material properties, such as shrinkage rates between low-temperature and medium-temperature waxes.

The lost wax investment casting process begins with the creation of a wax pattern, which is then assembled into a tree-like structure, coated with ceramic slurries, and fired to form a robust mold. After dewaxing, molten metal is poured into the cavity, and upon solidification, the ceramic shell is removed to reveal the final casting. Despite its advantages, this method is susceptible to dimensional variations due to factors like wax pattern accuracy, shell building parameters, and metal pouring conditions. For instance, in the production of a flange casting, critical dimensions may exceed tolerance limits, leading to scrap rates and increased costs. Through systematic analysis, I aim to elucidate how wax material selection—specifically, the shift from medium-temperature to low-temperature wax—impacts dimensional stability, and I will present experimental data to validate these findings.

To address the issue of dimensional超差 in flange castings, I first applied fault tree analysis (FTA), a deductive reasoning approach that starts with an undesired event (the顶事件) and traces back to potential root causes. In this case, the顶事件 was the deviation in flange dimensions, such as the outer diameter measuring beyond the specified tolerance of ϕ(70±0.55) mm and the cumulative dimension exceeding ϕ(96±0.55) mm. The fault tree was constructed by identifying intermediate events, including熔模尺寸不合格 (wax pattern dimensional inaccuracy),型壳材料更改 (shell material alterations), and浇注参数不当 (pouring parameter inconsistencies). By evaluating each branch, I determined that熔模尺寸不合格 was the primary contributor, as it directly influenced the final casting dimensions. Sub-events under this category involved wax material properties,模具设计 (mold design), and process controls. For example, the use of low-temperature wax, which has a different shrinkage behavior compared to medium-temperature wax, emerged as a key factor. This analytical approach allowed me to isolate the most probable causes and prioritize further investigation.

Complementing the fault tree analysis, I employed a fishbone diagram (also known as Ishikawa diagram) to visually map out all potential factors affecting wax pattern dimensional accuracy. The diagram categorized causes into six main areas: Man (human factors), Machine (equipment), Material (wax and other inputs), Method (process procedures), Environment (working conditions), and Measurement (inspection techniques). Under Material, for instance, the change from medium-temperature wax to low-temperature wax was identified as a critical element, as their distinct compositions—medium-temperature wax typically consists of rosin-wax bases, while low-temperature wax comprises 50% fully refined paraffin and 50% stearic acid—lead to varying收缩率 (shrinkage rates). Similarly, in the Method category, inconsistencies in process instructions, such as the lack of specific tolerance ranges for theoretical dimensions, contributed to the deviations. By systematically evaluating each末端因素 (end factor) through现场验证 (on-site verification) and调查分析 (investigative analysis), I confirmed that wax material substitution and inadequate process specifications were the root causes. This holistic analysis not only highlighted the interdependencies among factors but also provided a framework for implementing corrective actions in lost wax investment casting operations.

The heart of this investigation lies in understanding the shrinkage characteristics of wax materials used in lost wax investment casting. Shrinkage, defined as the reduction in size during cooling and solidification, can be quantified using the formula: $$ \text{Shrinkage Rate} = \frac{\text{Mold Dimension} – \text{Theoretical Dimension}}{\text{Theoretical Dimension}} \times 100\% $$ In the context of flange casting production, I conducted a comparative study between medium-temperature wax and low-temperature wax using the same mold. The mold dimensions were fixed, and multiple wax patterns were produced under identical conditions. The results, summarized in the table below, illustrate the average dimensions measured for each wax type and their corresponding shrinkage rates. This empirical approach is crucial for optimizing the lost wax investment casting process, as even minor variations in shrinkage can accumulate and lead to significant dimensional errors in the final castings.

| Theoretical Dimension (mm) | Mold Dimension (mm) | Wax Type | Average Measured Dimension (mm) | Shrinkage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 154.0 | 158.0 | Medium-Temperature | 155.74 | 1.014 |

| 154.0 | 158.0 | Low-Temperature | 156.50 | 1.010 |

| 70.0 | 72.4 | Medium-Temperature | 70.80 | 1.022 |

| 70.0 | 72.4 | Low-Temperature | 72.03 | 1.005 |

| 96.0 | 99.8 | Medium-Temperature | 97.66 | 1.022 |

| 96.0 | 99.8 | Low-Temperature | 99.03 | 1.008 |

As evidenced by the data, low-temperature wax exhibits a lower shrinkage rate compared to medium-temperature wax across various dimensions. For example, in the critical outer diameter of 70 mm, the shrinkage rate for medium-temperature wax is approximately 1.022%, whereas for low-temperature wax, it is only 1.005%. This difference, though seemingly small, results in a measurable increase in wax pattern dimensions when low-temperature wax is used, directly contributing to the observed dimensional超差 in the final castings. The relationship between wax type and dimensional accuracy can be further expressed mathematically by considering the cumulative effect of shrinkage on multiple features. For a flange casting with multiple diameters, the overall deviation Δ can be modeled as: $$ \Delta = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \text{Theoretical Dimension}_i \times \left(1 – \frac{\text{Shrinkage Rate}_i}{100}\right) \right) – \text{Theoretical Dimension}_{\text{total}} $$ where n represents the number of features, and the shrinkage rate varies based on the wax material. This formula underscores the importance of selecting appropriate wax types in lost wax investment casting to maintain dimensional integrity.

In addition to wax material properties, other factors in the lost wax investment casting process can exacerbate dimensional variations. For instance, the shell-building phase involves applying multiple layers of refractory coatings, and any inconsistency in parameters like temperature, humidity, or drying time can lead to shell distortion or cracking. During the dewaxing stage, if not properly controlled, residual stresses may cause wax patterns to deform, further affecting the final dimensions. Moreover, metal pouring parameters, such as temperature and velocity, play a critical role; deviations here can result in incomplete filling or thermal contractions that alter the casting geometry. To mitigate these risks, I recommend implementing real-time monitoring systems and statistical process control (SPC) in lost wax investment casting operations. By continuously tracking key variables—e.g., wax injection pressure, shell thickness, and pour temperature—manufacturers can detect anomalies early and adjust processes accordingly, thereby reducing the incidence of dimensional超差.

The experimental validation phase involved producing a batch of flange castings using both medium-temperature and low-temperature waxes under controlled conditions. All other parameters, such as shell materials, coating layers, and pouring temperatures, were kept constant to isolate the effect of wax type. The wax patterns were measured using calibrated instruments, and the data were analyzed to compute shrinkage rates. The results, as shown in the previous table, confirm that low-temperature wax patterns are consistently larger than their medium-temperature counterparts due to reduced shrinkage. This finding has profound implications for quality control in lost wax investment casting, as it highlights the need for material-specific process adjustments. For example, when switching from medium-temperature to low-temperature wax,模具设计 (mold design) should account for the lower shrinkage by potentially modifying the mold dimensions to compensate. This proactive approach can prevent dimensional超差 and enhance the overall yield of precision castings.

Furthermore, the fault tree and fishbone analyses revealed that human factors and measurement inaccuracies, though not primary causes in this instance, can still contribute to dimensional deviations in lost wax investment casting. For example, if operators fail to adhere to standardized procedures during wax injection or shell building, variations may arise. Similarly, inaccurate measurement tools can lead to false acceptances or rejections of castings. To address this, regular training and equipment calibration are essential. Additionally, the integration of advanced technologies, such as 3D scanning and digital twins, can provide more accurate dimensional assessments and simulate the effects of process changes before implementation. By fostering a culture of continuous improvement and leveraging data-driven insights, manufacturers can optimize the lost wax investment casting process for superior dimensional accuracy and reliability.

In conclusion, the dimensional超差 observed in flange castings produced via lost wax investment casting is predominantly attributable to the shrinkage characteristics of the wax materials used. Through systematic analysis using fault tree and fishbone diagrams, I identified that the substitution of medium-temperature wax with low-temperature wax, which has a lower shrinkage rate, results in larger wax patterns and subsequent casting dimensions beyond tolerance limits. The experimental data unequivocally demonstrate that for a given mold, low-temperature wax yields patterns with reduced contraction, leading to deviations in critical features such as outer diameters and cumulative dimensions. To mitigate these issues, it is imperative to conduct thorough material evaluations and adjust process parameters accordingly in lost wax investment casting operations. By emphasizing the importance of wax selection and implementing robust quality control measures, manufacturers can achieve higher precision, reduce scrap rates, and meet the stringent demands of industries reliant on this advanced casting technique. Ultimately, this study underscores the critical role of material science in enhancing the efficacy of lost wax investment casting and paves the way for future innovations in near-net-shape manufacturing.