In my extensive experience with materials engineering and foundry practices, I have encountered numerous cases where austempered ductile iron (ADI) components, particularly spiral bevel gears, exhibit premature failure. ADI, characterized by a unique matrix of bainitic ferrite and retained austenite, offers an exceptional combination of strength, ductility, and wear resistance, making it a prime candidate for replacing alloy forged steels like 20CrMnTi in gear applications. Its advantages include weight reduction, noise dampening, and energy efficiency. However, the realization of these benefits is critically dependent on meticulous control over the entire manufacturing process, from melting and casting to heat treatment. Any deviation can lead to significant casting defects and subsequent in-service failures. This article delves deeply into a detailed investigation of such failures, focusing on the root causes related to microstructure and casting defects, and presents robust solutions derived from first-hand analysis and process optimization.

The fundamental appeal of ADI lies in its microstructure. After the austempering heat treatment, the matrix consists of acicular bainite (or upper/lower bainite) and a substantial volume fraction (20-40%) of carbon-enriched, thermally stable austenite. This austenite provides remarkable toughness and, under service loads, can undergo transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) effect, leading to work hardening and enhanced wear and fatigue resistance. The chemical composition, graphite morphology, and heat treatment parameters are interlinked variables that dictate the final properties. Any imbalance can precipitate failure.

The production of manganese and copper-alloyed ADI gears begins with precise charge calculation and melting. I typically start with high-purity pig iron, such as Q12 grade, to minimize trace element interference. Melting is conducted in a medium-frequency induction furnace to ensure homogeneous temperature and composition. The target nominal composition, which serves as a baseline, is outlined in the table below. It is crucial to understand that these are not rigid numbers but a range that must be adjusted based on section size, casting design, and desired hardenability.

| Element | Target Nominal | Range from Failed Gear Analysis | Primary Function & Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 3.5 | 3.1 – 3.2* | Promotes graphite formation, increases graphite nodule count, stabilizes austenite, reduces shrinkage. Critical for volume expansion during solidification to counter casting defects like shrinkage porosity. |

| Si | 2.5 | 2.6 – 2.8 | Strong graphitizer, refines graphite nodules, suppresses carbide formation, promotes bainitic transformation, widens the process window for austempering. |

| Mn | 0.4 – 0.6 | 0.6 – 0.8 | Enhances hardenability by shifting C-curve right, but promotes severe segregation leading to “white bright areas” (martensite/carbides) in the matrix, degrading toughness. |

| Cu | 0.6 – 0.8 | 0.8 – 0.9 | Improves hardenability and uniformity, promotes pearlite in as-cast state, solid solution strengthens the matrix, exhibits negative segregation. |

| P | <0.04 | ~0.045 | Undesirable; forms brittle phosphide eutectic at grain boundaries, severely reducing impact strength. |

| S | <0.02 | ~0.023 | Undesirable; consumes magnesium, impairs nodularization, leading to vermicular graphite and related casting defects. |

| Mg | 0.03 – 0.05 | ~0.03 | Residual from nodularization; essential for maintaining spheroidal graphite shape. |

| RE | 0.02 – 0.04 | ~0.04 | Residual rare earths; aid in nodularization, counteract deleterious effects of trace elements like Ti, Sb. |

*Note: The low analyzed carbon in the failed gear is likely due to the sampling method (drill chips from surface) and does not reflect the true liquidus carbon. Accurate analysis requires spectroscopy on a properly prepared sample.

The heart of ductile iron production is the nodularization and inoculation process. In the case under investigation, the initial process used a冲入法 (sandwich method) with 1.3% FeSiMg8RE3 alloy. I found this amount to be insufficient. The reaction kinetics can be described by the yield efficiency of magnesium, which is influenced by temperature, sulfur content, and process control. A simplified mass balance for magnesium is:

$$ [Mg]_{final} = [Mg]_{added} \cdot Y – [Mg]_{lost\ to\ S\ and\ oxidation} $$

where $Y$ is the yield efficiency, typically 30-50%. To achieve a residual Mg > 0.04%, the addition must be calculated accordingly. Inoculation with 75% ferrosilicon, totaling 0.9%, was performed but lacked intensity. In my revised process, I advocate for a dual-inoculation strategy: primary inoculation in the ladle and a decisive post-inoculation (e.g., stream inoculation during pouring) to enhance nodule count. The number of graphite nodules per unit area ($N_v$) is a critical parameter inversely related to graphite size and directly linked to mechanical properties. It can be estimated from 2D metallographic measurements:

$$ N_v \approx \frac{2N_A}{D} $$

where $N_A$ is the number of nodules per unit area and $D$ is the mean nodule diameter. Higher $N_v$ leads to a more uniform stress distribution and better performance.

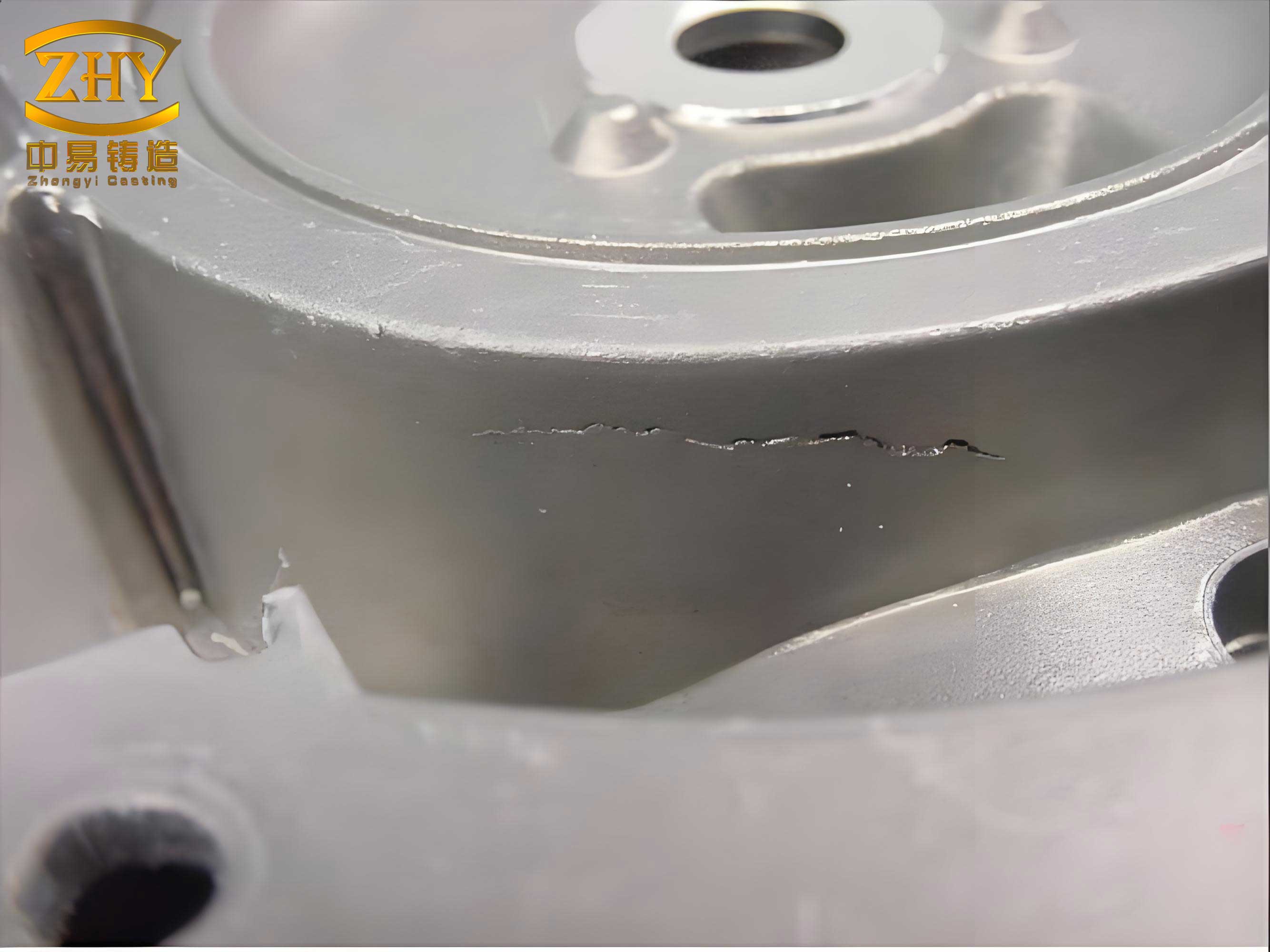

Casting is a stage rife with potential for casting defects. The original practice employed horizontal pouring in green sand molds with a symmetrical parting line. This is a common source of problems. The upper surface of a horizontally poured casting is prone to slag inclusion, gas entrapment, and dross formation due to turbulence and temperature gradients. Furthermore, feeding solidification can be inefficient, leading to shrinkage porosity, another critical internal casting defect. The manifestation of such defects is not always immediately visible but acts as stress concentrators under cyclic loading. The figure below illustrates typical subsurface discontinuities that can originate from poor casting practice.

After machining, the gears undergo austempering heat treatment: austenitization at 900±10°C for 2 hours followed by rapid quenching into a salt bath at 370±5°C for 2 hours. This isothermal hold allows the diffusion-controlled bainitic transformation. The kinetics of this transformation can be modeled by the Johnson-Mehl-Avrami-Kolmogorov (JMAK) equation for phase fraction transformed ($f$):

$$ f = 1 – \exp(-k t^n) $$

where $k$ is a rate constant dependent on temperature and composition, $t$ is time, and $n$ is the Avrami exponent. The stability of the austenite is paramount. Its carbon content ($C_{\gamma}$) after austempering, which dictates its mechanical stability, can be approximated from the initial bulk carbon and the fraction of bainitic ferrite formed. High silicon content is beneficial as it inhibits carbide precipitation during the bainitic hold, allowing carbon to partition solely into the austenite.

The failure mode observed in the field after approximately 37,000 km of service was surface crushing and spalling (pitting) on the tooth flanks. Spalling is a surface fatigue phenomenon where subsurface cracks initiate, propagate, and eventually link to cause material detachment. The primary drivers are sub-surface stress exceeding the material’s endurance limit, often exacerbated by microstructural inhomogeneities or casting defects. In this case, macro-examination revealed not only the spalled craters but also small gas holes on the tooth surface at the parting line, a clear signature of a casting defect.

My comprehensive failure analysis involved multiple techniques. Chemical analysis was performed via optical emission spectroscopy on samples taken from the gear body. The results, compared to targets, are in Table 1. The elevated manganese and copper, coupled with potentially low effective carbon due to poor graphite morphology, set the stage for problems. Metallographic examination is the most revealing. Samples were sectioned, mounted, polished, and etched with 4% nital. The as-cast graphite structure was evaluated per standards like ASTM A247. The findings were alarming.

| Parameter | Measured Value | Acceptable Range for High-Performance ADI | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodularity | 77.6% | >90% | Poor. Presence of vermicular and exploded graphite drastically reduces load-bearing capacity and fatigue strength. |

| Nodule Count (nodules/mm²) | ~120 | >150 | Insufficient. Low count leads to larger graphite spheres, promoting stress concentration. |

| Graphite Size (μm) | 6 – 42 | Predominantly 20-30 μm, uniform | Excessive size variation and large maximum size are detrimental. | Matrix: White Bright Areas | Present (~3-5 vol%) | 0% (ideally) | Hard, brittle regions of martensite/retained austenite with high carbon (M/A islands) due to Mn segregation. Act as internal notches. |

The low nodularity is a direct consequence of inadequate magnesium treatment and insufficient inoculation. Graphite acts as a void in the matrix; spheroidal shapes minimize stress concentration. The stress concentration factor $K_t$ for an elliptical cavity is given by:

$$ K_t = 1 + 2\sqrt{\frac{a}{b}} $$

where $a$ and $b$ are the major and minor axes. For a sphere, $a=b$, so $K_t = 3$. For vermicular graphite, $a >> b$, leading to a much higher $K_t$, dramatically reducing fatigue life. The presence of manganese-rich white bright areas is equally critical. Manganese, having a segregation coefficient $k < 1$, enriches in the last-to-freeze intercellular regions. Upon austempering, these regions, with their high hardenability, may transform to martensite or high-carbon austenite instead of bainite. The local hardness can exceed 700 HV, while the surrounding bainitic matrix is around 350-400 HV. This mismatch promotes crack initiation under cyclic contact stresses.

Hardness testing provided further clues. The core hardness was 32 HRC, the general surface was 35 HRC, but the contact surface (flank) exhibited 53 HRC. This significant increase is evidence of the TRIP effect. The contact stress $\sigma_c$ in gear meshing, approximated by the Hertzian contact stress formula for curved surfaces, is:

$$ \sigma_c = \sqrt{ \frac{F}{\pi L} \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2}}{\frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}} } $$

where $F$ is load, $L$ is face width, $R$ is radius of curvature, $E$ is Young’s modulus, and $\nu$ is Poisson’s ratio. This high stress induces plastic deformation in the surface layers, transforming the metastable retained austenite to martensite, thereby increasing hardness and wear resistance—a beneficial effect if the base microstructure is sound. However, with pre-existing casting defects and poor graphite, this work-hardened layer can spall off.

The root cause analysis clearly points to two intertwined issues: sub-optimal metallurgical structure and preventable casting defects. To address these, I implemented a multi-pronged corrective action plan.

1. Enhanced Nodularization and Inoculation: The nodularizing alloy addition was increased to 1.6-1.8%, with careful control of pouring temperature (1480-1550°C) to improve magnesium recovery. Inoculation was intensified using a FeSiBa alloy for longer-lasting effect and supplemented with immediate stream inoculation using a specialized FeSi inoculant at 0.1% during pouring. This boosted nodule count to over 200 nodules/mm² and nodularity above 95%. The relationship between inoculant addition and nodule count is not linear but follows a saturation curve, which must be determined for each foundry setup.

2. Composition Optimization: Manganese content was strictly capped at 0.6%. To maintain hardenability for the gear’s section size (which dictates the critical diameter $D_c$), copper was adjusted to the range of 0.7-0.8%. The combined hardenability effect can be estimated using multiplying factors. Silicon was maintained at 2.6-2.8% to suppress carbide formation and white bright areas. The carbon equivalent (CE) was kept high to improve fluidity and feeding:

$$ CE = \%C + \frac{\%Si + \%P}{3} $$

A CE above 4.3 is generally targeted for good castability, but must be balanced against graphite flotation.

3. Radical Change in Casting Practice to Eliminate Casting Defects: The horizontal pouring was completely abandoned. A vertical gating system was designed with the spiral bevel gear segment placed at the bottom of the mold cavity. A sizable riser (feeder) was placed at the top of the gear shaft section. This promotes directional solidification from the gear teeth (which are critical and require soundness) towards the riser. The riser remains molten longest, feeding shrinkage throughout solidification. The Chvorinov’s rule governs solidification time $t$:

$$ t = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where $V$ is volume, $A$ is surface area, $B$ is a mold constant, and $n$ is typically 2. By designing the casting so the modulus ($V/A$) increases towards the riser, shrinkage porosity is eliminated. This vertical placement also minimizes turbulence and slag/gas entrapment on the critical gear tooth surfaces. After implementing this, radiographic inspection confirmed the absence of gas holes and shrinkage cavities—the most pernicious casting defects were eradicated.

4. Heat Treatment Refinement: The austempering temperature was fine-tuned to 365°C to obtain a finer bainitic structure. A mandatory tempering step at 300°C for 3 hours was introduced after austempering. This tempering helps to relieve residual stresses and, more importantly, allows carbon to further diffuse from any potential fine carbides in the bainitic ferrite into the austenite, stabilizing it further and slightly tempering any unavoidable martensite in segregated zones, reducing their brittleness. The volume fraction of retained austenite ($V_{\gamma}$) can be measured by X-ray diffraction and should ideally be between 25-35% after this process.

The effectiveness of these measures was validated through rigorous bench testing per automotive drive axle standards and subsequent field trials. The improved gears showed no signs of spalling or crushing beyond normal wear, and their service life exceeded design expectations. The key learning is that ADI’s superior properties are not automatic; they are earned through rigorous control of every step. Casting defects are not merely surface imperfections; they are often the initiators of catastrophic fatigue failures. Similarly, minor deviations in chemistry—like excess manganese—can have disproportionate effects by creating microscopic stress raisers in the matrix.

In conclusion, the failure of ADI spiral bevel gears is a systems problem, often rooted in foundational process steps. My analysis underscores that substandard graphite morphology—low nodularity, low nodule count, large size—combined with matrix inhomogeneities like white bright areas from segregation, are the primary metallurgical causes of surface fatigue failure. These are frequently compounded by, and sometimes originate from, avoidable casting defects such as gas holes and shrinkage porosity resulting from non-optimal gating and feeding design. The solution pathway is clear: aggressive inoculation and proper nodularization to perfect the graphite phase; tight compositional control, especially limiting manganese; and a casting methodology centered on directional solidification and minimal turbulence. By adhering to these principles, ADI can reliably deliver its promise of high performance, durability, and efficiency in demanding gear applications, moving from a material of potential to one of proven and consistent excellence.