In my extensive experience in the field of metallurgy and automotive component manufacturing, I have witnessed the transformative potential of Austempered Ductile Iron (ADI) as a material for engine crankshafts. ADI, often referred to as austempered ductile iron internationally, represents a significant advancement over conventional ductile iron and even some alloy steels. Its unique combination of high strength, ductility, wear resistance, and cost-effectiveness makes it an ideal candidate for demanding applications like crankshafts in internal combustion engines. This article delves into the comprehensive development and application process of ADI crankshafts, from material composition and casting techniques to heat treatment, machining, and performance validation. I will emphasize the critical role of advanced casting methods, particularly sand coated iron mold casting, and incorporate various tables and formulas to summarize key technical data.

The journey of producing a high-performance ADI crankshaft begins with stringent control over the molten iron chemistry. To ensure consistent mechanical properties and minimize casting defects, the raw materials must be of high quality. Based on my work, two primary charge material approaches are viable: one using 100% high-quality steel scrap combined with alloying elements and carbon raisers, and another utilizing a 50/50 blend of high-quality pig iron and steel scrap with similar additions. The target chemical composition, crucial for achieving the desired matrix structure after austempering, is meticulously controlled as shown in Table 1.

| Element | Composition (wt.%) |

|---|---|

| C | 3.60 – 3.80 |

| Si | 2.20 – 2.60 |

| Mn | 0.25 – 0.45 |

| S | < 0.025 |

| P | < 0.045 |

| Cu | 0.40 – 0.65 |

| Mo | 0.25 – 0.45 |

| Mg | 0.040 – 0.045 |

Sulfur is kept extremely low to reduce the tendency for gas porosity and shrinkage, while phosphorus is minimized to mitigate low-temperature brittleness. ADI can be categorized into alloyed and non-alloyed types. In our pursuit of cost-effectiveness without compromising performance, we have successfully developed and validated non-alloyed ADI grades for crankshaft applications through numerous comparative trials.

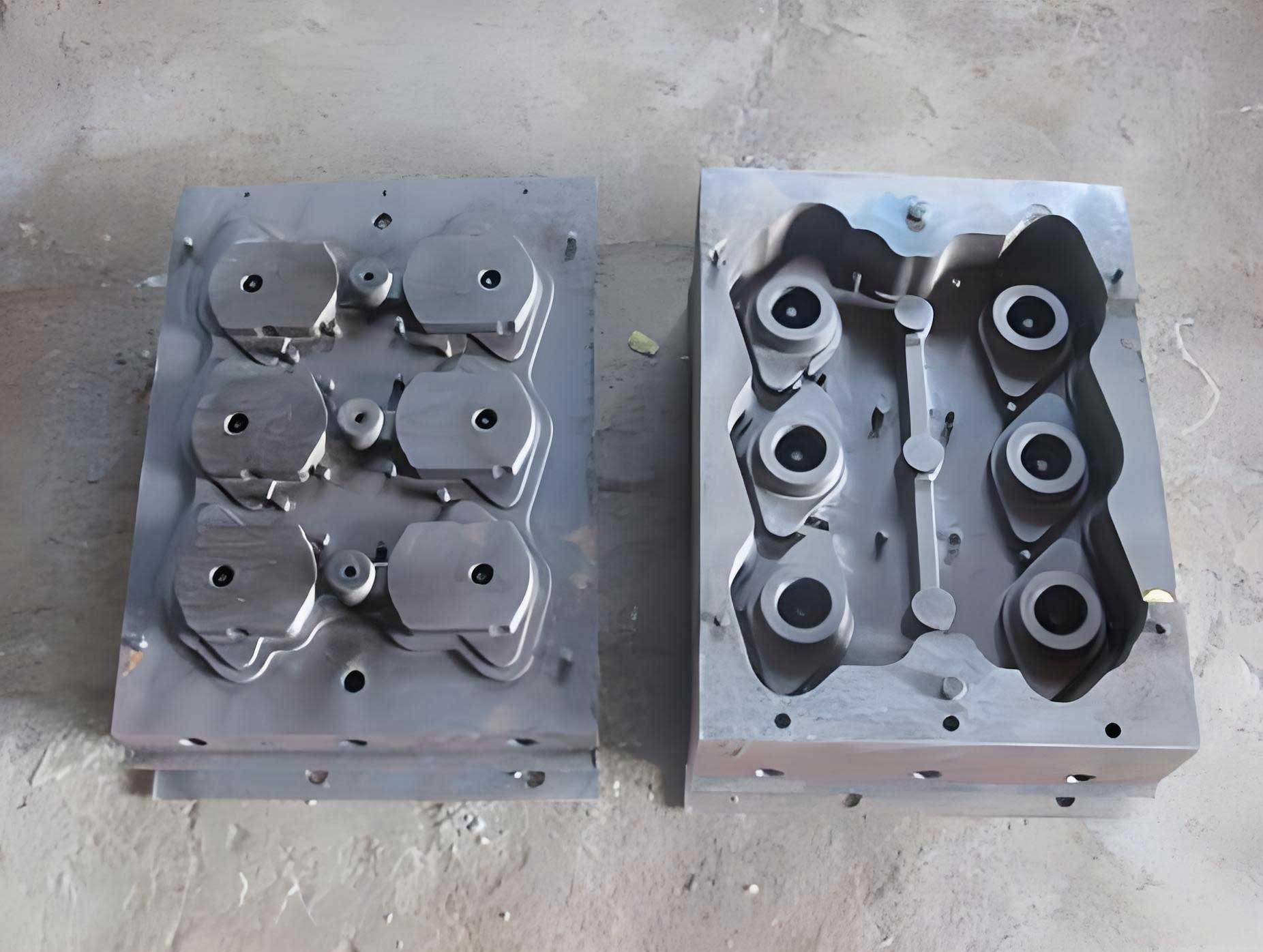

The choice of casting process is paramount for obtaining sound, high-quality crankshaft castings with uniform microstructure. Several processes are employed, including shell molding, resin sand molding, and green sand molding. However, from my perspective, two processes stand out for mass production of crankshafts: shell molding and sand coated iron mold casting. The sand coated iron mold casting process, in particular, offers exceptional stability, rapid cooling rates, excellent surface finish, and a significant reduction in common defects like shrinkage, gas holes, and slag inclusions. The rapid solidification inherent in sand coated iron mold casting refines the graphite nodule size and improves nodularity consistency, which is foundational for superior ADI properties.

Shell molding is often more advantageous for crankshaft castings below 20 kg in weight, while sand coated iron mold casting demonstrates superior control for heavier components above 20 kg. The quality control protocols during pouring are similar for both: stable sources for raw materials, timely mold replacement, strict adherence to furnace-front parameters, skilled operators, and continuous technical oversight. In our development program, we have validated crankshaft blanks produced via both methods, with a strong focus on optimizing the sand coated iron mold casting technique. Factories proficient in these methods, especially sand coated iron mold casting, can consistently achieve a comprehensive scrap rate below 3%. The as-cast microstructure and properties typically meet the benchmarks outlined in Table 2.

| Parameter | Target Value |

|---|---|

| Nodularity Grade | 1-3 |

| Graphite Size Grade | 5-8 |

| Matrix Ferrite Content | ~75% |

| Tensile Strength | 700 – 850 MPa |

| Elongation | 4.0 – 6.0 % |

| Hardness (HBW) | 190 – 240 |

The core of ADI’s superior properties lies in its unique heat treatment: austempering. The desired final microstructure is acicular ferrite (often called bainitic ferrite) surrounded by stable, high-carbon austenite. This structure is not a classical bainite but a distinct matrix that provides an outstanding combination of strength and toughness. Referring to standards like GB/T 24733-2009 (or analogous international standards), the relevant ADI grades for crankshafts are summarized in Table 3. Our development focused primarily on QTD800-10 and QTD1050-6.

| Grade | Main Wall Thickness (mm) | Min. Tensile Strength, Rm (MPa) | Min. Yield Strength, Rp0.2 (MPa) | Min. Elongation, A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTD800-10 | ≤ 30 | 800 | 500 | 10 |

| QTD900-8 | ≤ 30 | 900 | 600 | 8 |

| QTD1050-6 | ≤ 30 | 1050 | 700 | 6 |

| QTD1200-3 | ≤ 30 | 1200 | 850 | 3 |

Determining the optimal austempering cycle is critical. For castings produced via sand coated iron mold casting where the as-cast structure contains minimal free carbides and phosphide eutectic (<3%), a single-step austempering process is often sufficient. However, to ensure complete dissolution of any carbides and achieve a homogeneous austenite, a two-stage process can be employed. The first stage involves a high-temperature graphitization anneal: 890–930°C for 2.5 hours, followed by furnace cooling to obtain a predominantly ferritic matrix. The second, and definitive, stage is the austempering cycle itself. The established parameters from our trials are: Austenitizing at 880–920°C for 2 hours, followed by rapid quenching into a salt bath maintained at 370–390°C for 2 hours for isothermal transformation.

The transformation kinetics during the isothermal hold can be conceptually described by the Avrami equation for phase transformation:

$$ f = 1 – \exp(-k t^n) $$

where \( f \) is the transformed fraction, \( k \) is a rate constant dependent on temperature and composition, \( t \) is time, and \( n \) is the Avrami exponent. For the formation of acicular ferrite in ADI, the rate constant \( k \) is highly sensitive to the isothermal temperature. The goal is to avoid the nose of the pearlite transformation curve and complete the bainitic reaction within the specified time. The process window must be carefully controlled; rapid transfer from the austenitizing furnace to the salt bath is essential to prevent pearlite formation.

Validation of this heat treatment on crankshafts, particularly those from sand coated iron mold casting, yielded excellent results. Samples taken from the counterweights showed a consistent microstructure and mechanical properties, as tabulated in Table 4.

| Sample ID | Target Grade | Nodularity Grade | Graphite Size | Matrix Structure | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Hardness (HBW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-1 | QTD800-10 | 2 | 6 | Acicular Ferrite + Austenite | 890 | 12.0 | 285 |

| I-2 | QTD800-10 | 2 | 6 | Acicular Ferrite + Austenite | 880 | 11.2 | 280 |

| II-1 | QTD1050-6 | 2 | 6 | Acicular Ferrite + Austenite | 1054 | 10.2 | 295 |

| II-2 | QTD1050-6 | 2 | 6 | Acicular Ferrite + Austenite | 1042 | 10.8 | 300 |

The achieved hardness range of 30-35 HRC (approximately 285-332 HBW) has significant implications for both performance and machinability. Firstly, this inherent hardness provides excellent wear resistance to the crankshaft journals. In fact, our research and literature indicate that the wear resistance of ADI journals at this hardness level is comparable to that of pearlitic ductile iron crankshafts with induction-hardened journals (45-50 HRC). This eliminates the need for a separate surface hardening process like induction hardening, simplifying production and reducing cost. Furthermore, when combined with fillet rolling, the surface finish and near-surface hardness are further enhanced, leading to superior fatigue performance.

However, this higher hardness presents challenges during machining. Compared to machining pearlitic ductile iron (250-300 HBW), operations like turning, drilling, and tapping on ADI (305-332 HBW) are more difficult. The material’s higher yield strength, lower thermal conductivity, and pronounced work-hardening tendency demand more robust tooling. We encountered frequent breakage of standard high-speed steel drills and taps, especially for oil holes and threaded holes. The solution lies in advanced tool materials. We found that carbide-tipped or solid carbide drills and taps are necessary for efficient and reliable machining. For even harder ADI grades or more aggressive machining, coated carbide tools or advanced ceramic tools (e.g., alumina-silicon carbide composites) show promise. The machining parameters must be optimized, often involving lower speeds and feeds than used for softer irons. The relationship between tool life (T) and cutting speed (V) can be approximated by Taylor’s tool life equation:

$$ VT^n = C $$

where \( n \) and \( C \) are constants specific to the tool-workpiece combination. For ADI, the exponent \( n \) is generally lower than for plain ductile iron, indicating a greater sensitivity of tool life to cutting speed, necessitating more conservative machining parameters.

Post-machining, fillet rolling is a critical process to induce beneficial compressive residual stresses in the high-stress concentration areas of the crankshaft fillets, dramatically improving fatigue strength. The rolling force (F) must be carefully calculated based on the crankshaft geometry, nominal operating bending moment (Mnom), and the desired safety factor (SF). A simplified analytical model for required contact pressure can be derived from Hertzian contact theory and the desired sub-surface stress state. The nominal bending stress at the fillet is given by:

$$ \sigma_{nom} = \frac{M_{nom} \cdot y}{I} $$

where \( y \) is the distance from the neutral axis to the outer fiber, and \( I \) is the area moment of inertia. The rolling process aims to create a compressive residual stress (\( \sigma_{res} \)) such that the resultant stress (\( \sigma_{nom} + \sigma_{res} \)) under load remains below the fatigue limit. The applied rolling force is then determined iteratively based on finite element analysis or empirical data from strain-gauge measurements during rolling.

We conducted extensive bending fatigue tests on both QTD800-10 and QTD1050-6 ADI crankshafts after fillet rolling. For a Type I crankshaft (QTD800-10) with a nominal operating moment of 504 N·m, the test results, summarized in Table 5, demonstrated a high safety factor.

| Sample No. | Test Bending Moment (N·m) | Result | Cycles to Failure (×105) | Failure Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 950 | Run-out (≥107) | 1000 | N/A |

| 1-4 | 1000 | Run-out | 1000 | N/A |

| 2-4 | 1050 | Run-out | 1000 | N/A |

| 2-2 | 1200 | Run-out | 1000 | N/A |

| 3-3 | 1500 | Failed | 7 | Connecting Rod Journal Fillet |

| 3-1 | 1400 | Failed | 1.6 | Connecting Rod Journal Fillet |

| 4-1 | 1250 | Run-out | 1000 | N/A |

| 5-1 | 1300 | Failed | 2.3 | Connecting Rod Journal Fillet |

| 6-3 | 1250 | Failed | 5.5 | Connecting Rod Journal Fillet |

Statistical analysis of such data, using methods like the staircase technique or maximum likelihood estimation, allows for the determination of the median fatigue limit. For this batch, the fatigue limit was around 1120-1200 N·m, yielding a safety factor (SF = Fatigue Limit / Mnom) well above 2.0, which exceeds the typical industry requirement of 1.6-1.8. Subsequent engine bench tests and field trials confirmed the robustness and reliability of these ADI crankshafts.

The application prospects for ADI crankshafts are exceptionally promising. The current automotive landscape is characterized by intense cost pressure alongside demands for higher performance and efficiency. Traditionally, forged steel crankshafts (e.g., from 40Cr, 42CrMo) have been used for high-output, turbocharged engines, while pearlitic ductile iron crankshafts serve naturally aspirated engines. ADI bridges this gap. It offers mechanical properties that can match or exceed those of many forged steels at a significantly lower cost—often half or less of the cost of a comparable forged steel crankshaft. This cost advantage stems from the inherent near-net-shape capability of casting processes like sand coated iron mold casting, which drastically reduces material waste and machining compared to forging.

The sand coated iron mold casting process is a key enabler for this cost-effective production of high-integrity ADI crankshaft blanks. Its stability and quality consistency are fundamental to achieving the reproducible chemistry and microstructure required for successful austempering. As foundries worldwide become more proficient with sand coated iron mold casting technology, the availability and quality of ADI castings will only improve. Furthermore, the maturation of austempering heat treatment facilities and a growing body of knowledge on ADI processing are creating a favorable ecosystem for its adoption.

In conclusion, the development and application of ADI for engine crankshafts represent a significant technological and economic opportunity. Through meticulous control of chemistry, leveraging advanced casting techniques like sand coated iron mold casting, optimizing the austempering heat treatment, adapting machining strategies, and validating performance via rigorous testing, ADI crankshafts can reliably meet the demands of modern engines. The non-alloyed approach we pursued further enhances its cost competitiveness. As the automotive industry continues to seek lightweight, strong, and affordable components, ADI is poised to replace not only higher-grade ductile iron crankshafts but also to make substantial inroads into applications currently reserved for forged steel. The journey from a novel material to a mainstream engineering solution is well underway, and sand coated iron mold casting is playing a pivotal role in this transformation. Future work will undoubtedly focus on refining alloy designs for even more demanding applications, optimizing the integration of casting and heat treatment for sand coated iron mold casting products, and further improving machinability through collaborative efforts with tooling manufacturers.