In my extensive work on casting process development, I have encountered numerous challenges with complex components, particularly shell castings for automotive applications. The transmission housing for heavy trucks is a prime example of such a demanding shell casting. This article details the comprehensive journey from initial design to final optimization of the casting process for an HT200 gray iron transmission housing. The focus is on overcoming structural complexities and defect minimization, with repeated emphasis on the intricacies inherent to producing large, thin-walled shell castings.

The transmission housing is a critical assembly in heavy-duty vehicles, and its integrity is paramount for performance and durability. As a shell casting, it features a hollow, barrel-like structure with internal partitions, multiple bore openings, and varied wall thicknesses. The primary challenge lies in achieving sound casting free from defects like porosity, cold shuts, and misruns, which are common pitfalls in such voluminous shell castings. The material specification is HT200 gray iron, requiring a minimum tensile strength of 200 MPa and a controlled hardness range.

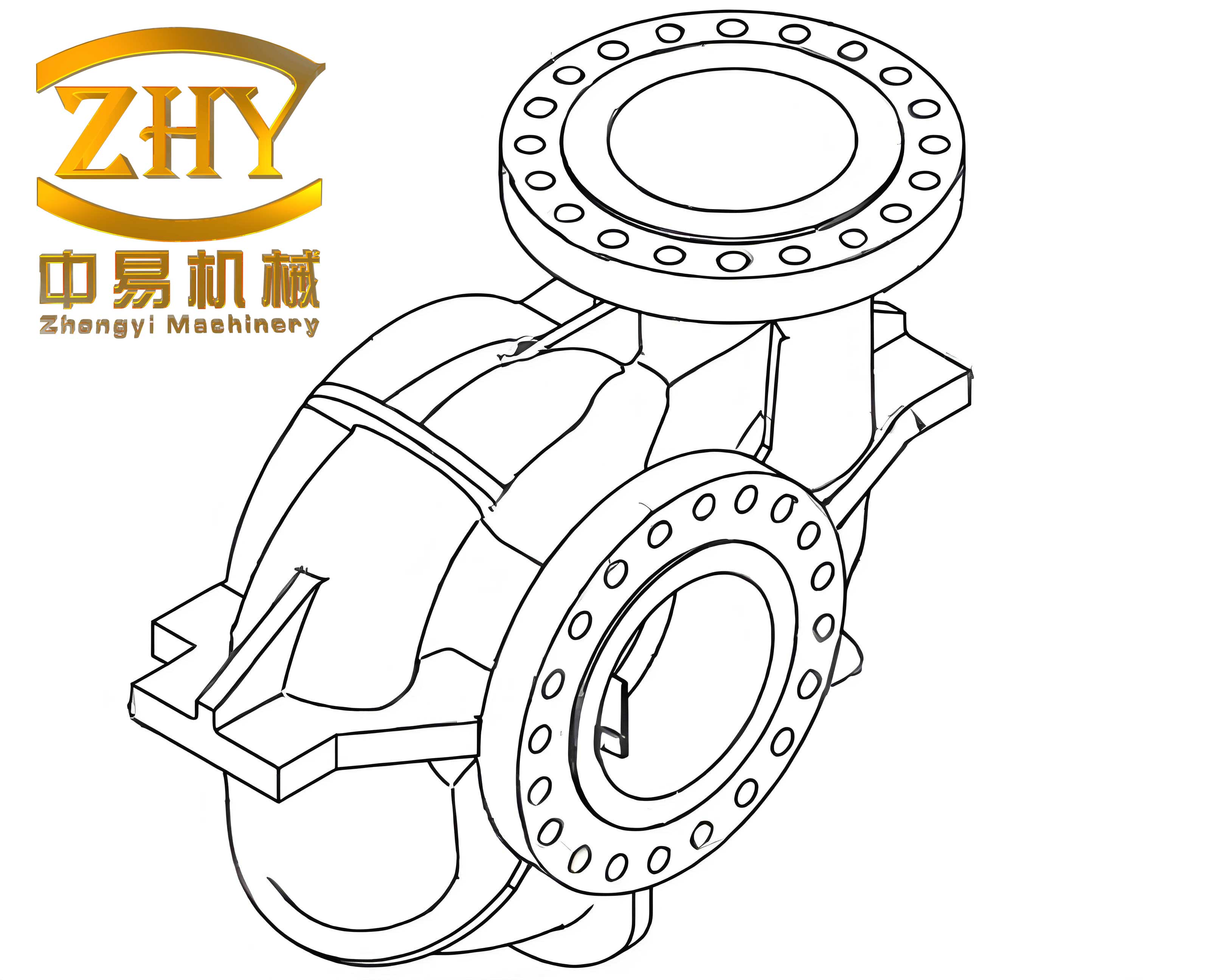

The fundamental geometry of this specific transmission housing, a key shell casting, is outlined below. The design necessitates precise control over dimensional tolerances and internal soundness.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Material | HT200 Gray Iron |

| Approximate Single Weight | 85 kg |

| Overall Dimensions (L x W x H) | 525 mm x 565 mm x 385 mm |

| Nominal Wall Thickness | 8 mm |

| Dimensional Tolerance | 0 to +2 mm |

| Required Tensile Strength | ≥ 200 MPa |

| Hardness (HB) | 170 – 220 |

The initial phase of process development involved selecting an appropriate overall strategy. Given the production environment and the nature of this large shell casting, a horizontal parting line and green sand molding on a high-pressure molding line were chosen. The mold dimensions were 1500 mm x 1100 mm x 400 mm (cope) / 400 mm (drag). To maximize productivity, two castings were arranged per mold. The parting plane was strategically placed at the central axis of the three main bearing bores to simplify pattern drafting and core placement.

Core making presented a significant challenge due to the size and complexity of the internal cavity. The main cavity core was massive, weighing nearly 100 kg when combined. Manual handling and positioning were impractical. Therefore, a core assembly strategy was adopted. The two primary cores forming the main cavity were produced using the cold box process for adequate strength and dimensional stability. Two smaller cores for the idler shaft bosses were made from shell sand (coated sand) using a hot box machine. This combination of processes is often beneficial for complex shell castings. The cores were assembled using adhesives and mechanical fasteners on a dedicated fixture before being placed into the mold as a single unit using an automated manipulator. This approach is crucial for maintaining accuracy in such voluminous shell castings.

The design of the sand cores is a critical success factor for defect-free shell castings. Several key features were incorporated:

- Lightening Cavities: The large #1 and #2 cores were hollowed out to reduce weight and save core sand, which is especially important for large shell castings.

- Core Print Design: Core prints were modified with trapezoidal sections and sand collection grooves to ensure precise location and prevent sand crushing during mold closure.

- Mold Protection: Anti-crush rings and clearances were designed into the cope mold to prevent damage to the sand cores during closing. Seal grooves were added to prevent metal penetration.

- Handling Features: Slots for lifting clamps and recesses for assembly bolts were integrated into the core design.

- Error-Proofing: Asymmetric locators on the small idler boss cores (#3, #4) prevented incorrect assembly orientation.

The gating and feeding system is the lifeline of any casting process, more so for thin-walled shell castings requiring rapid fill. The design was based on hydraulic principles to ensure a controlled, non-turbulent fill. The first step was calculating the optimal pouring time.

The pouring time \( t \) (in seconds) is often estimated using the formula:

$$ t = S \sqrt{G} $$

where \( S \) is a wall thickness coefficient (taken as 1.85 for medium sections), and \( G \) is the total mass of metal in the mold (in kg). Assuming a casting yield of 85% for two castings:

$$ G = \frac{2 \times 85 \text{ kg}}{0.85} \approx 200 \text{ kg} $$

Therefore,

$$ t = 1.85 \times \sqrt{200} \approx 1.85 \times 14.14 \approx 26.2 \text{ s} $$

The next critical parameter is the choke area, which is the smallest cross-sectional area in the gating system controlling the flow rate. The required choke area \( F_{\text{choke}} \) (in cm²) is calculated using:

$$ F_{\text{choke}} = \frac{G}{0.31 \mu t \sqrt{H_p}} $$

Where:

\( \mu \) = total resistance coefficient (taken as 0.32 for gray iron in green sand molds).

\( H_p \) = mean effective metallostatic head height (in cm).

\( G \) = mass of metal flowing through the choke (170 kg for two castings, ignoring the gating system for this part of the calculation).

With a cope height \( H = 40 \) cm and casting height \( C = 38.5 \) cm:

$$ H_p = H – \frac{C}{8} = 40 – \frac{38.5}{8} = 40 – 4.81 = 35.2 \text{ cm} $$

Substituting the values:

$$ F_{\text{choke}} = \frac{170}{0.31 \times 0.32 \times 26.2 \times \sqrt{35.2}} $$

First, calculate \( \sqrt{35.2} \approx 5.93 \).

Then denominator: \( 0.31 \times 0.32 = 0.0992 \); \( 0.0992 \times 26.2 \approx 2.60 \); \( 2.60 \times 5.93 \approx 15.42 \).

Thus,

$$ F_{\text{choke}} = \frac{170}{15.42} \approx 11.02 \text{ cm}^2 $$

Applying a safety factor of 1.2 for practical foundry conditions common in shell castings production:

$$ \sum F_{\text{choke}} = 11.02 \times 1.2 = 13.22 \text{ cm}^2 $$

A semi-continuous gating system (initially choked, then open) was selected to promote non-turbulent filling. The cross-gate was designated as the choke. Its area \( F_{\text{cross}} \) was set equal to \( \sum F_{\text{choke}} \), dimensioned at 33 mm x 40 mm = 13.2 cm². To enhance slag trapping, a ceramic foam filter was incorporated. The area ratios were designed as \( F_{\text{sprue}} : F_{\text{cross}} : F_{\text{filter}} : \sum F_{\text{ingate}} = 1.1 : 0.75 : 4.5 : 1 \).

From these ratios:

Sprue area: \( F_{\text{sprue}} = \frac{1.1}{0.75} \times F_{\text{cross}} = 1.467 \times 13.2 \approx 19.4 \text{ cm}^2 \), corresponding to a standard sprue diameter of 50 mm (area ≈ 19.63 cm²).

Filter required area: \( F_{\text{filter}} = \frac{4.5}{0.75} \times F_{\text{cross}} = 6 \times 13.2 = 79.2 \text{ cm}^2 \). A filter with dimensions 240 mm x 32 mm (76.8 cm²) was used, which is acceptable for these shell castings.

Total ingate area: \( \sum F_{\text{ingate}} = \frac{1}{0.75} \times F_{\text{cross}} = 1.333 \times 13.2 \approx 17.6 \text{ cm}^2 \). This was divided into four ingates, each with a trapezoidal section of 26/30 mm width and 8 mm height.

| Component | Area Ratio | Calculated Area (cm²) | Selected Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprue | 1.1 | 19.4 | Ø 50 mm |

| Cross Gate (Choke) | 0.75 | 13.2 | 33 x 40 mm |

| Filter | 4.5 | 79.2 | 240 x 32 mm |

| Total Ingates (4) | 1.0 | 17.6 | 4 x (26/30 x 8 mm) |

Venting is paramount for resin-bonded cores used in shell castings, as they generate substantial gas during pouring. The initial venting design placed multiple vent pins at the highest points of the cope, including above the core prints. However, this proved insufficient.

Metallurgical control is equally vital. For HT200 shell castings, the chemical composition must be tightly controlled to achieve the desired microstructure and mechanical properties. The target range and the rationale are summarized below.

| Element | Target Range (wt.%) | Role and Control Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.1 – 3.5 | Ensures adequate fluidity and graphite formation. Higher carbon improves castability but reduces strength. |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.6 – 2.0 | Promotes graphitization, counteracts chilling. Si/C ratio is critical for matrix structure. |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.7 – 1.0 | Neutralizes sulfur as MnS, strengthens the pearlite matrix. |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤ 0.12 | Kept low to minimize formation of iron sulfides, which can promote shrinkage and embrittlement. |

| Phosphorus (P) | ≤ 0.12 | Kept low to avoid the formation of brittle phosphide eutectic networks. |

The pouring temperature was maintained between 1370°C and 1420°C to ensure complete filling of the thin sections in these large shell castings within the 30-second target pour window. The microstructure was controlled to limit cementite content to less than 3% by volume.

The initial trial production, based on the above design, revealed a significant quality issue. The rejection rate exceeded 15%, with over 80% of defects identified as blowholes (subsurface porosity). This is a classic problem in complex shell castings where gas entrapment occurs. Analysis indicated that while vent pins were numerous, the geometry of the casting and the gating layout created gas pockets. The highest points of the cavity were near the ingates. During rapid filling, gases generated from the cores and mold atmosphere were trapped in these pockets and forced into the solidifying metal, creating invasive blowholes. This experience underscored a critical lesson for shell castings: vent placement must consider the dynamic flow of metal and the natural escape paths for gas, not just static high points.

The solution involved a fundamental revision of the orientation. The casting was inverted in the mold (i.e., the original “top” became the “bottom” relative to the parting line). This repositioned the massive core assembly and changed the geometry of the cavity relative to the gating. The new orientation allowed the natural buoyancy of gases to carry them toward the now-highest points, which were remote from the ingates. Furthermore, the venting system was enhanced. Instead of simple round pins, wedge-shaped collective venting risers were placed at both ends of the core prints to efficiently channel gas from the core prints. Additional vent pins were strategically placed on seven of the housing’s top bosses. The gating system design remained unchanged. This modified layout for producing these shell castings is illustrated in the final process schematic.

The impact of this optimization was profound. Subsequent production runs demonstrated a drastic reduction in blowhole defects. The rejection rate for these critical shell castings fell from over 15% to a stable level below 3%. This validated the process and highlighted the importance of dynamic gas evacuation planning in the casting of large, complex shell components.

To generalize the learning, the key steps for developing a robust process for similar heavy-section shell castings can be encapsulated in a systematic approach. The following table summarizes the critical phases and their focus areas.

| Phase | Key Activities | Technical Considerations for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Geometry & Feasibility Analysis | Review 3D model, identify thin/thick sections, undercuts, core complexity. | Simulate solidification and filling. Assess draft angles and parting line selection for the shell structure. |

| 2. Overall Process Strategy | Select molding method, parting line, number of castings per mold, core-making process. | Balance between productivity (multiple shell castings per mold) and dimensional control. Choose core process based on size and complexity. |

| 3. Detailed Design | Gating, feeding, venting, core design, pattern equipment design. | Use hydraulic calculations for gating. Design generous venting from cores and high points. Incorporate error-proofing in cores. |

| 4. Prototype & Trial | Produce initial tooling, execute trial runs, conduct non-destructive testing (NDT). | Monitor fill time and temperature. Inspect for porosity, cold shuts, and core shift in the initial shell castings. |

| 5. Defect Analysis & Optimization | Root cause analysis of defects (e.g., porosity mapping). Modify process parameters or geometry. | For gas defects, re-evaluate venting strategy and metal fill dynamics specific to the shell casting geometry. |

| 6. Final Validation & Production | Implement optimized process, establish control limits for metallurgy and process variables. | Document stable process windows for chemical composition, pouring temperature, and cycle times for consistent shell casting quality. |

In conclusion, the successful development of a casting process for a heavy truck transmission housing, a representative large and intricate shell casting, hinges on a methodical and iterative approach. The journey from a 15%+ rejection rate to under 3% underscores several universal principles. Firstly, theoretical calculations for gating provide a necessary starting point but must be validated empirically. Secondly, for shell castings employing substantial resin-bonded cores, venting design is not a static afterthought but a dynamic system that must align with the metal flow and gas generation patterns. Simply placing vents at the highest points is insufficient if those points are in zones of turbulent or late filling. Inverting the casting was the pivotal change that resolved the gas entrapment issue. Finally, tight control over metallurgical parameters—composition, temperature, and microstructure—forms the foundation for achieving the required mechanical properties in these high-integrity shell castings. The lessons learned are directly applicable to the broader family of complex, thin-walled shell castings across the automotive and heavy machinery sectors. Future work could involve more advanced simulation tools to predict gas entrapment and optimize vent placement virtually before first trial, further reducing development time and cost for such challenging shell castings.