In my experience working in a high-volume foundry, addressing defects like porosity in casting has always been a critical challenge. Porosity in casting, particularly for complex components such as engine blocks, significantly impacts structural integrity, pressure tightness, and overall product quality. This article delves into a detailed investigation conducted at our facility, where we focused on how pouring temperature influences the occurrence of porosity in casting for a diesel engine block. The goal was to optimize the process to minimize defects and enhance reliability.

The engine block in question, similar to the Cummins 6BT design, is a highly intricate casting with thin walls (approximately 5.0 mm), integral water pump, oil cooler, and oil pump housings. Its complexity makes it prone to defects, especially porosity in casting, which historically accounted for scrap rates as high as 11.1%. Despite previous improvements, porosity in casting remained at 9.6%, necessitating a deeper analysis. Our production setup uses a bottom-gating system with a pouring time of 21–22 seconds, coupled with venting and feeding risers at the top and front faces. We operate on a high-pressure automated line with green sand molds, where mold permeability exceeds 120, moisture content is 3.1–3.6%, and mold hardness ranges from 55 to 70. Cores are made from low-gas evolution materials: the water jacket cores use high-temperature resistant coated sand with gas evolution ≤18 mL, coated with zircon-based alcohol paint, while the cylindrical cores employ low-nitrogen furan resin sand with gas evolution ≤16 mL, coated with water-based graphite paint. All cores are dried twice before use to further reduce gas generation.

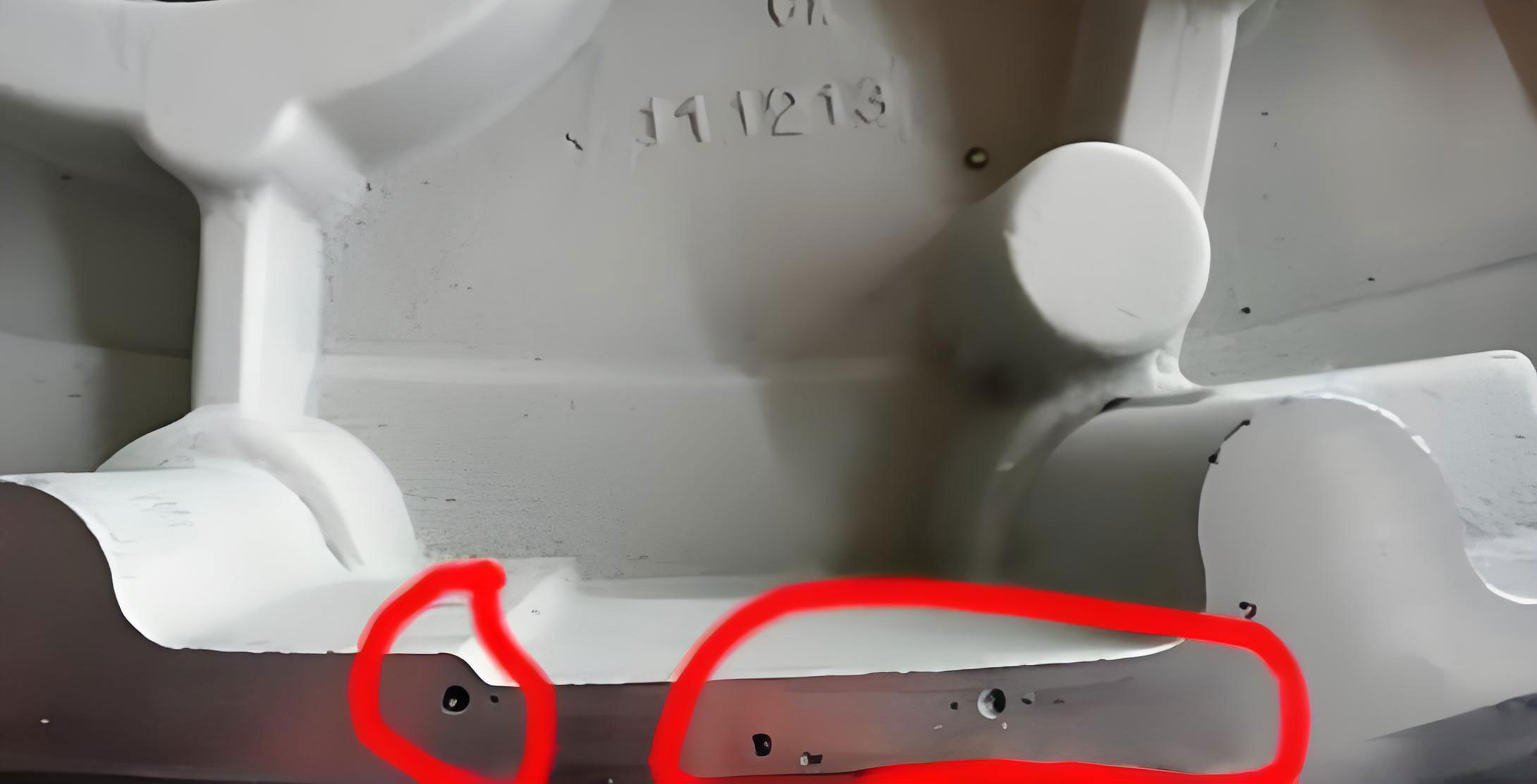

Porosity in casting primarily manifested in critical areas: the cylinder bores, oil cooler region, upper surfaces of the water jacket, and the water pump area. These locations are often associated with core gas evolution and inadequate venting. To quantify the impact of pouring temperature, we tracked a production batch of engine blocks, recording porosity defects relative to the temperature measured for the first casting from each ladle. The data, summarized in Table 1, revealed a strong correlation between low pouring temperatures and high scrap rates due to porosity in casting.

| Pouring Temperature Range (°C) | Number of Castings with Porosity | Percentage of Total Scrap (%) |

|---|---|---|

| < 1430 | 26 | 74.3 |

| 1430 – 1450 | 7 | 20.0 |

| 1450 – 1460 | 2 | 5.7 |

This table clearly indicates that over 74% of porosity in casting occurrences were linked to pouring temperatures below 1430°C. The original process specified a range of 1400–1440°C, which appeared suboptimal. Consequently, we hypothesized that increasing the pouring temperature to 1430–1460°C could mitigate porosity in casting by improving metal fluidity and gas escape. To test this, we implemented the adjusted temperature range in mass production and collected data over a significant period, as shown in Table 2.

| Production Period | Number of Castings Produced | Number of Castings Scrapped Due to Porosity | Porosity Scrap Rate (%) | Pouring Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to Adjustment | 6488 | 626 | 9.6 | 1400 – 1440 |

| After Adjustment | 8051 | 419 | 5.2 | 1430 – 1460 |

The results demonstrated a substantial reduction in porosity in casting scrap rate by 4.4 percentage points, a 46% decrease. This confirms that optimizing pouring temperature is a key lever for controlling porosity in casting. To understand this phenomenon fundamentally, we must explore the underlying mechanisms. Porosity in casting arises from entrapped gases—either from mold/core gas evolution or air entrainment—during solidification. The relationship between temperature and gas behavior can be described using physical models.

First, consider the solubility of gases in molten iron. Hydrogen and nitrogen solubility decreases as temperature drops, leading to gas precipitation and bubble formation. The solubility can be approximated by Sieverts’ law: $$ C = k \sqrt{P} e^{-\frac{\Delta H}{RT}} $$ where \( C \) is gas concentration, \( P \) is partial pressure, \( \Delta H \) is enthalpy of solution, \( R \) is gas constant, \( T \) is temperature, and \( k \) is a constant. Lower pouring temperatures reduce solubility, increasing the risk of gas bubble nucleation and contributing to porosity in casting.

Second, fluid dynamics play a crucial role. In a bottom-gating system, metal flows upward, and the upper sections of the casting, such as the cylinder bores and water jacket tops, experience lower superheat. This reduces fluidity and increases surface tension, making it harder for gas bubbles to escape. The surface tension \( \sigma \) of molten iron decreases with temperature, as given by: $$ \sigma = \sigma_0 – \alpha (T – T_0) $$ where \( \sigma_0 \) is surface tension at reference temperature \( T_0 \), and \( \alpha \) is a positive coefficient. At higher pouring temperatures (e.g., 1430–1460°C), surface tension is lower, facilitating bubble detachment and flotation. Additionally, the increased temperature maintains higher fluidity for longer, allowing better feeding through risers to compensate for shrinkage and gas entrapment, thereby reducing porosity in casting.

Third, core gas evolution is a major contributor to porosity in casting. The total gas volume \( V_g \) released from cores can be modeled as: $$ V_g = A \int_{0}^{t} G(t) \, dt $$ where \( A \) is core surface area, \( G(t) \) is gas evolution rate over time \( t \). At lower metal temperatures, the solidification front advances faster, trapping gas bubbles before they can vent. Higher pouring temperatures slow solidification, extending the time available for gas escape through vents and risers. To quantify this, we can relate the bubble rise velocity \( v_b \) to temperature via Stokes’ law, modified for molten metal: $$ v_b = \frac{2 r^2 (\rho_m – \rho_g) g}{9 \eta} $$ where \( r \) is bubble radius, \( \rho_m \) and \( \rho_g \) are densities of metal and gas, \( g \) is gravity, and \( \eta \) is dynamic viscosity of the metal. Viscosity \( \eta \) decreases with temperature, so higher pouring temperatures increase \( v_b \), promoting bubble removal and reducing porosity in casting.

We conducted further experiments to correlate pouring temperature with specific defect metrics. Table 3 expands on the data, incorporating additional parameters like mold moisture and core gas levels to show multi-factorial interactions affecting porosity in casting.

| Batch ID | Average Pouring Temp (°C) | Mold Moisture (%) | Core Gas Evolution (mL) | Porosity Defect Count | Defect Density (defects per casting) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 1415 | 3.4 | 17 | 42 | 0.85 |

| B2 | 1440 | 3.3 | 16 | 18 | 0.36 |

| B3 | 1455 | 3.2 | 15 | 9 | 0.18 |

| B4 | 1430 | 3.5 | 18 | 25 | 0.50 |

| B5 | 1460 | 3.1 | 14 | 5 | 0.10 |

This table illustrates that higher pouring temperatures consistently correlate with lower porosity in casting, even when other variables fluctuate. To optimize the process, we developed a predictive model for porosity risk \( P_r \) as a function of pouring temperature \( T_p \), mold moisture \( M \), and core gas \( G \): $$ P_r = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_p + \beta_2 M + \beta_3 G + \epsilon $$ where \( \beta \) are coefficients determined via regression. Our analysis yielded \( \beta_1 < 0 \), confirming the inverse relationship between temperature and porosity in casting.

Beyond the technical aspects, the economic impact of reducing porosity in casting is substantial. With an annual production of 35,000 engine blocks, the 4.4% reduction in scrap translates to significant cost savings. The financial benefit \( S \) can be estimated as: $$ S = N \times \Delta R \times C_u $$ where \( N \) is annual production volume, \( \Delta R \) is reduction in scrap rate (0.044), and \( C_u \) is unit cost per casting. Assuming a conservative cost model, this resulted in savings exceeding $2.46 million annually, highlighting the importance of controlling porosity in casting through temperature management.

In conclusion, our investigation underscores that pouring temperature is a dominant factor in mitigating porosity in casting for complex engine blocks. By raising the range from 1400–1440°C to 1430–1460°C, we achieved a 46% decrease in scrap due to porosity in casting. This improvement stems from enhanced metal fluidity, reduced surface tension, and prolonged gas escape windows, all critical for minimizing porosity in casting. Future work will explore integrating real-time temperature monitoring with automated feedback loops to further stabilize the process and reduce variability. Ultimately, mastering these parameters is essential for advancing foundry practices and ensuring high-integrity castings free from detrimental porosity in casting.