As a researcher focused on wear-resistant materials, I have extensively studied the performance of alloyed white cast iron under severe service conditions. The application of slurry pumps for transporting abrasive media, such as sand-laden water, presents a significant challenge due to shell erosion. To promote the use of cost-effective chromium-manganese-copper (Cr-Mn-Cu) alloy white cast iron in these components, a detailed investigation into its erosion resistance is essential. This article presents my findings from a comprehensive study comparing the slurry erosion behavior of as-cast and heat-treated Cr-Mn-Cu alloy white cast iron, analyzing the failure mechanisms to provide a solid experimental foundation for its industrial application.

The core advantage of alloy white cast iron lies in its hard, wear-resistant carbide phases embedded within a metallic matrix. The composition and treatment of this alloy white cast iron critically determine the morphology, distribution, and hardness of these carbides, as well as the properties of the surrounding matrix. In this study, I designed a specific alloy white cast iron composition to investigate the synergistic effects of chromium, manganese, and copper after heat treatment. The targeted chemical composition (in wt.%) was as follows:

| Element | C | Cr | Mn | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt.%) | 2.8 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 2.5 | Balance |

The material was melted in a vacuum induction furnace and cast into ceramic shells. Specimens for erosion testing were machined from the castings. In addition to the as-cast condition, two distinct heat treatment regimens were applied to alter the microstructure of the alloy white cast iron, as detailed below.

| Sample Designation | Heat Treatment Protocol |

|---|---|

| As-Cast (AC) | No heat treatment (reference state) |

| HT1 | Austenitized at 800°C for 2 hours, air-cooled, then tempered at 500°C for 0.5 hours. |

| HT2 | Austenitized at 800°C for 6 hours, air-cooled, then tempered at 500°C for 1 hour. |

The prolonged austenitization for HT2 was intended to promote greater alloy element homogenization and carbide stabilization within the white cast iron structure.

To evaluate performance, I measured bulk hardness (Rockwell C scale) and impact toughness. More critically, microhardness testing was conducted separately on the carbide phases and the metallic matrix to understand the contribution of each constituent. The slurry erosion test was designed to simulate the working environment of a pump volute. A mixture of 5 kg of quartz sand (20-40 mesh) and 6.67 liters of pure water was used as the erosive medium. Tests were conducted on a rotating disc-type erosion tester at a controlled velocity of 2.8 m/s. The relative erosion resistance, $\beta$, was defined as the ratio of the mass loss of the as-cast reference sample to the mass loss of the tested sample, following the equation:

$$ \beta = \frac{\Delta m_{AC}}{\Delta m_{sample}} $$

where $\Delta m$ is the cumulative mass loss after a standardized test duration. A higher $\beta$ value indicates superior erosion resistance. Each sample was tested multiple times to ensure statistical reliability.

The results from mechanical and erosion testing are consolidated in the table below. The data clearly shows that heat treatment significantly enhances the properties of this alloy white cast iron.

| Property | As-Cast (AC) | HT1 | HT2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (HRC) | 54.0 | 61.6 | 61.5 |

| Microhardness – Matrix (HV) | 585.2 | 630.5 | 825.1 |

| Microhardness – Carbide (HV) | 911.1 | 1027.1 | 1235.8 |

| Impact Toughness (J/cm²) | 3.46 | 4.01 | 5.76 |

| Erosion Mass Loss (g) | 0.0143 | 0.0125 | 0.0106 |

| Relative Erosion Resistance ($\beta$) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.14 | 1.35 |

The HT2 sample exhibited the most remarkable combination of properties. While its bulk hardness was similar to HT1, its matrix microhardness showed a dramatic increase of over 40% compared to the as-cast white cast iron. Most notably, the carbide microhardness in HT2 was approximately 36% higher than in the as-cast material. This directly correlated with the highest impact toughness and the best erosion resistance, which was 1.35 times that of the baseline as-cast white cast iron.

Fractographic analysis of impact specimens provided insights into the toughness results. The as-cast white cast iron exhibited a predominantly cleavage fracture surface, characteristic of brittle failure. In contrast, both HT1 and HT2 samples showed mixed-mode fractures with cleavage facets surrounded by fine dimples, indicative of microvoid coalescence. The HT2 sample displayed a finer and more uniform distribution of these dimples, explaining its superior impact toughness. This ductile component in the fracture mechanism can be qualitatively linked to the presence of stabilized, high-carbon austenite (retained austenite) in the matrix after heat treatment, which imparts enhanced strain tolerance to the alloy white cast iron.

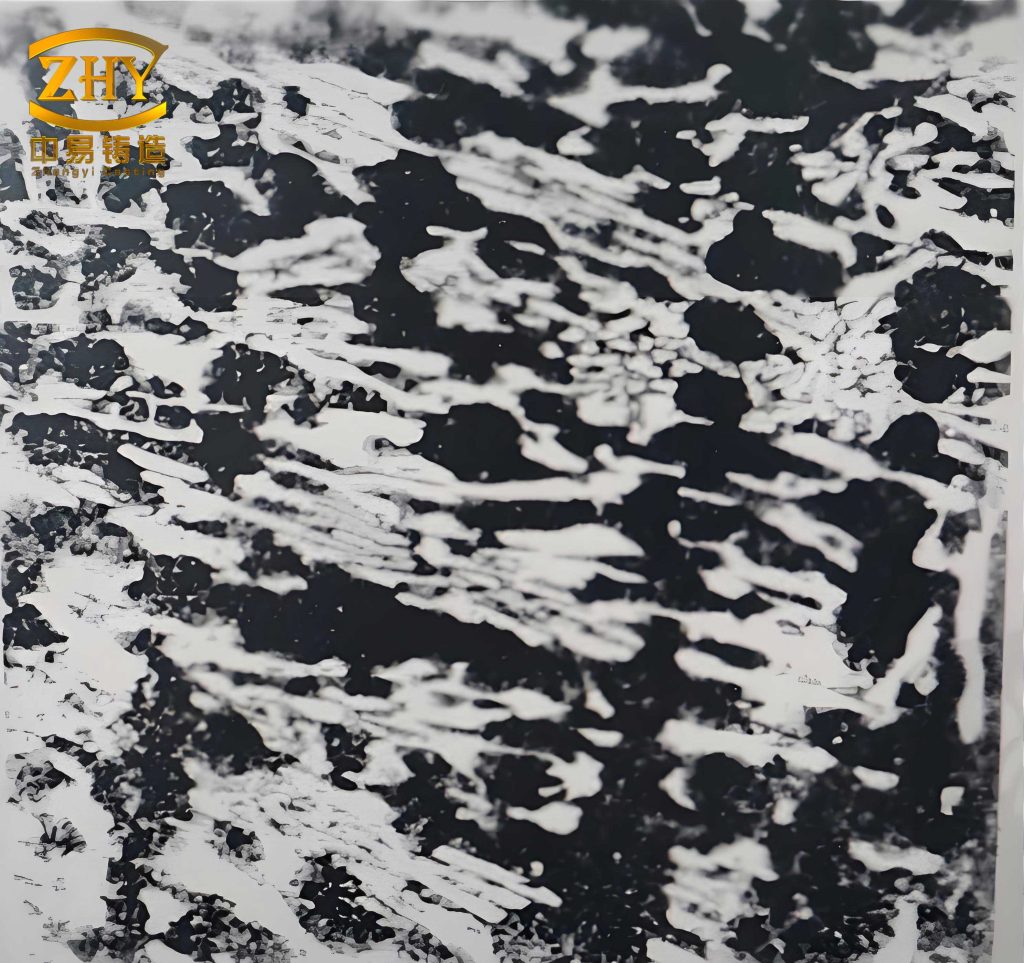

The erosion mechanism was studied by examining the worn surfaces and cross-sections. The as-cast white cast iron surface showed deep, wide gouges, pronounced plowing, and severe lip formation, with clear directional scratches and numerous carbide pull-outs. This morphology indicates a material removal process dominated by micro-cutting and brittle fracture of unsupported carbides. The HT1 surface showed similar but less severe features. Remarkably, the HT2 surface was comparatively smoother with shallow, less defined grooves and minimal evidence of large-scale carbide fracture and spalling.

Cross-sectional analysis under the eroded surface revealed the underlying microstructural interactions. In the as-cast white cast iron, the soft pearlitic matrix was easily worn away, leaving the primary carbides exposed and vulnerable to fracture at their roots. The connection between carbide fracture rate and matrix wear rate can be conceptualized. If the matrix wear depth per unit time is $W_m$ and the critical exposure height for carbide fracture is $h_c$, then the time to fracture a carbide, $t_f$, is related by:

$$ t_f \propto \frac{h_c}{W_m} $$

A faster matrix wear rate ($W_m$) leads to quicker exposure and fracture of carbides. In the heat-treated samples, especially HT2, the matrix was significantly harder and more erosion-resistant, slowing down $W_m$. Furthermore, the carbides themselves were harder, increasing their resistance to micro-cracking. The matrix in HT2 also contained a dispersion of fine secondary carbides and a significant amount of retained austenite. The retained austenite, while not the hardest phase, can undergo strain-induced transformation to martensite under impact, providing a degree of work hardening and absorbing energy. This composite-like structure—ultra-hard primary carbides, a strengthened matrix with secondary hardening particles, and a ductile phase—creates a synergistic defense against erosive particles. The hard carbides protect the matrix from direct cutting, while the tough, hardened matrix firmly supports the carbides, preventing their premature loss. This synergy is the key reason for the superior performance of the heat-treated chromium-manganese-copper alloy white cast iron.

In conclusion, this investigation demonstrates that appropriate heat treatment is not merely an optional step but a crucial one for optimizing the service performance of alloy white cast iron for abrasive erosion applications. The specific treatment involving extended austenitization (HT2 protocol) transformed the microstructure of the chromium-manganese-copper alloy white cast iron, leading to a remarkable synergy between phase hardness and toughness. The achieved 35% improvement in relative erosion resistance, coupled with a 66% increase in impact toughness compared to the as-cast state, is highly significant for engineering applications. The enhanced performance stems from the development of extremely hard carbide phases that resist cutting, combined with a strengthened and toughened matrix that provides robust support. These findings provide a strong technical basis for selecting and processing this cost-effective grade of alloy white cast iron for components exposed to severe slurry erosion, such as pump casings, impellers, and pipeline fittings.