In my research, I have explored methods to enhance the toughness and strength of white cast iron, a material traditionally considered brittle and unsuitable for demanding applications. Through years of experimentation, I found that isothermal quenching can significantly improve the comprehensive mechanical properties of white cast iron, particularly impact resistance, by transforming the microstructure to lower bainite and fragmenting the continuous carbide network. However, to further push the boundaries, I investigated the effects of hot forging on white cast iron, followed by heat treatments, aiming to refine the carbide morphology and distribution while optimizing the matrix structure. This approach has led to remarkable improvements in performance, challenging the conventional notion that white cast iron cannot undergo plastic deformation. In this article, I will detail my findings on the forgeability, microstructural evolution, mechanical properties, and wear resistance of forged white cast iron, emphasizing the synergistic effects of deformation and heat treatment. The keyword ‘white cast iron’ will be central to our discussion, as we delve into how this material can be transformed into a high-performance alloy for wear-resistant components.

My study began with the melting and casting of white cast iron specimens. I used a medium-frequency induction furnace with a capacity of 50 kg, charging scrap steel and adding crushed graphite electrodes as a carburizer. The molten metal was overheated to approximately 1500°C, sampled for composition analysis, and then deoxidized with aluminum before pouring. Two primary compositions were investigated, with carbon contents of 2.8% and 3.6%, respectively, to assess the influence of carbon on forgeability and properties. The chemical compositions are summarized in Table 1.

| Sample ID | C (%) | Si (%) | Mn (%) | P (%) | S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Carbon White Cast Iron | 2.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| High-Carbon White Cast Iron | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

For forging trials, I prepared cast billets with dimensions of 30 mm × 30 mm × 150 mm. These were heated in a flame furnace to 1150°C and forged into flat bars with a final thickness of 10 mm, achieving a thickness reduction ratio of 66.7%. The forgeability was evaluated through torsion and bending tests at elevated temperatures, demonstrating that white cast iron, especially the lower-carbon variant, possesses excellent plastic deformation capability in the austenitic state. No edge cracks were observed in the low-carbon white cast iron after deformation, while the high-carbon white cast iron showed minor surface cracks only at the edges, without propagation. This confirms that white cast iron can indeed be hot-worked, opening new avenues for its processing and application.

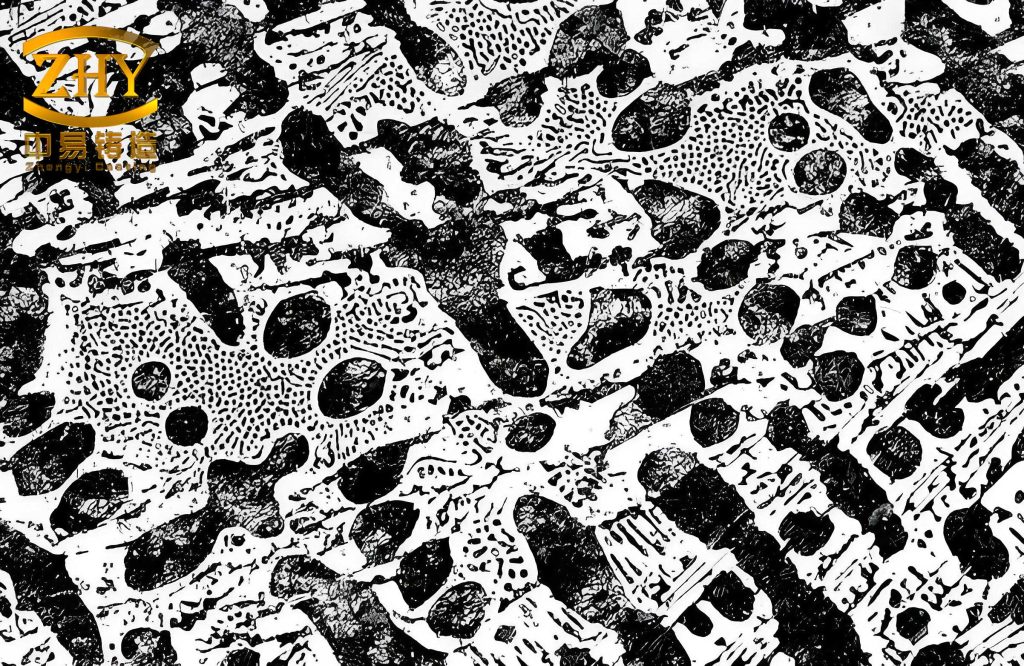

The microstructural changes induced by forging were examined using metallographic analysis. In the as-cast state, white cast iron exhibits a network of eutectic carbides (ledeburite) within a pearlitic or martensitic matrix, depending on cooling conditions. After forging with a reduction ratio of 66.7%, the continuous carbide network is fragmented and aligned along the forging direction. In cross-sections perpendicular to the forging direction, the carbides appear more isolated and refined. This is particularly evident in low-carbon white cast iron, where the carbide network is nearly completely broken into discrete particles. In high-carbon white cast iron, some continuity of carbides remains due to the higher volume fraction. Additionally, forging introduces dislocations in the austenite, which serve as nucleation sites for fine carbide precipitation during cooling, leading to a dispersion of small carbides in the matrix. Subsequent isothermal quenching at 280°C further modifies the microstructure: carbides undergo spheroidization and refinement, while the matrix transforms to lower bainite with retained austenite. However, large blocky eutectic carbides persist, indicating that forging alone may not fully eliminate them, necessitating optimized deformation processes.

To quantify the mechanical properties, I conducted tensile, bending, and impact tests on specimens with varying forging reduction ratios (from 0% to 80%). The results are presented in Table 2. The as-cast white cast iron showed relatively low strength and toughness, with tensile strength around 40-50 kg/mm² and impact toughness below 0.5 kg·m/cm². After forging, these properties improved dramatically: tensile strength increased to approximately 100-120 kg/mm², bending strength doubled, and impact toughness rose by over threefold. Hardness decreased slightly due to microstructural changes. Further enhancement was achieved by combining forging with isothermal quenching, which boosted tensile strength to 140-160 kg/mm² and hardness by about 10 HRC units, though impact toughness remained similar to the forged state. The relationship between forging reduction ratio and mechanical properties can be expressed using empirical formulas. For instance, the tensile strength (σ_t) as a function of reduction ratio (R) for low-carbon white cast iron follows: $$ \sigma_t = 40 + 1.2R \quad (\text{in kg/mm}^2) $$ where R is in percentage. Similarly, impact toughness (a_k) shows a logarithmic increase: $$ a_k = 0.3 \ln(R + 1) \quad (\text{in kg·m/cm}^2). $$ These formulas highlight the strengthening effect of deformation.

| Condition | Tensile Strength (kg/mm²) | Bending Strength (kg/mm²) | Impact Toughness (kg·m/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-Cast | 45 | 80 | 0.4 | 55 |

| Forged (66.7% reduction) | 110 | 180 | 1.5 | 50 |

| Forged + Isothermal Quenched | 150 | 220 | 1.6 | 60 |

The microstructural basis for these improvements lies in several mechanisms. Forging refines the austenite grains and introduces a substructure of dislocations and subgrain boundaries, which enhance strength via work hardening. The fragmentation of carbides reduces stress concentrations and improves matrix continuity. Isothermal quenching then stabilizes the matrix with tough phases like retained austenite, while spheroidizing carbides minimizes crack initiation sites. Scanning electron microscopy of impact fracture surfaces revealed a transition from brittle cleavage in as-cast white cast iron to ductile dimples in forged specimens, confirming the increased toughness. This underscores the potential of thermo-mechanical processing for white cast iron.

Wear resistance is a critical property for white cast iron applications. I conducted abrasive wear tests under high-stress (using a pin-on-disk machine) and low-stress (using a sand abrasion tester) conditions. The relative wear resistance (ε) was calculated as: $$ \varepsilon = \frac{\Delta W_{\text{standard}}}{\Delta W_{\text{sample}}} $$ where ΔW is weight loss. Standard samples were quenched high-manganese steel for high-stress tests and normalized low-carbon steel for low-stress tests. Results are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

| Material | Hardness (HRC) | Weight Loss (g/m) | Relative Wear Resistance (ε) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Manganese Steel | 50 | 0.15 | 1.0 |

| As-Cast White Cast Iron | 55 | 0.08 | 1.88 |

| Forged White Cast Iron | 50 | 0.12 | 1.25 |

| Forged + Quenched White Cast Iron | 60 | 0.07 | 2.14 |

| Material | Hardness (HRC) | Weight Loss (g) | Relative Wear Resistance (ε) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Carbon Steel | 20 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| As-Cast White Cast Iron | 55 | 0.3 | 3.33 |

| Forged White Cast Iron | 50 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

| Forged + Quenched White Cast Iron | 60 | 0.25 | 4.0 |

Under high-stress conditions, as-cast white cast iron outperformed high-manganese steel due to its high hardness resisting micro-cutting. Forged white cast iron showed reduced wear resistance because of lower hardness and increased plastic deformation leading to fatigue wear. However, after isothermal quenching, hardness increased, and wear resistance improved. In low-stress conditions, forged white cast iron exhibited the best performance, as the combination of refined carbides and a tougher matrix mitigated fatigue and brittle fracture. This suggests that wear mechanisms depend on stress levels: high stress favors hardness, while low stress requires a balance of hardness and toughness. Analysis of worn surfaces via scanning electron microscopy revealed grooves and dimples, indicative of combined micro-cutting and fatigue processes.

In conclusion, my research demonstrates that white cast iron is not inherently brittle but can be effectively strengthened and toughened through forging and heat treatment. The key findings are: Firstly, white cast iron exhibits excellent forgeability in the austenitic temperature range (1100-900°C), with lower carbon content enhancing plastic deformation. Secondly, forging significantly improves mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and impact toughness, by refining microstructure and fragmenting carbides. Thirdly, subsequent isothermal quenching further optimizes the matrix and carbide morphology, unlocking additional performance gains. Fourthly, wear resistance is context-dependent; hardness alone is insufficient, and a synergy with toughness is crucial for low-stress applications. These insights redefine white cast iron as a versatile material for wear-resistant components, paving the way for innovative manufacturing processes. Future work should explore advanced thermo-mechanical routes to fully dissolve eutectic carbides and tailor properties for specific service conditions.