As a researcher in the field of metallurgy, I have long been fascinated by the unique properties of white cast iron. This material, characterized by its high carbon content and the presence of cementite (Fe3C) in its microstructure, offers exceptional wear resistance due to the hard carbide networks. Historically, white cast iron has been utilized in various industrial applications, dating back to ancient times. For instance, in China during the Spring and Autumn Period, white cast iron was used for plowshares, demonstrating its early adoption as a耐磨 material. However, the inherent brittleness of white cast iron, stemming from the continuous carbide network that acts as stress concentrators, severely limits its application under impact loads. This brittleness can be described by fracture mechanics principles, such as the Griffith crack theory, where the critical stress for fracture is given by: $$\sigma_c = \sqrt{\frac{2E\gamma}{\pi a}}$$ Here, $\sigma_c$ is the fracture stress, $E$ is the Young’s modulus, $\gamma$ is the surface energy, and $a$ is the crack length. In white cast iron, the carbide networks effectively act as initial cracks, reducing $\sigma_c$ and leading to low impact toughness.

The quest to improve the performance of white cast iron, particularly its impact toughness, has driven extensive research globally. Traditional approaches have focused on alloying with elements like chromium, nickel, and molybdenum to modify the microstructure. For example, the development of nickel-hard white cast iron and high-chromium white cast iron in the early 20th century marked a shift from pearlitic to martensitic matrices, enhancing hardness and wear resistance. However, these alloys rely on scarce and expensive elements, and the improvement in impact toughness remains modest, typically not exceeding 1.0 kg·m/cm². The chemical compositions and mechanical properties of these alloyed white cast irons are summarized in Table 1 below.

| Type of White Cast Iron | Chemical Composition (wt%) | Tensile Strength (kg/mm²) | Bending Strength (kg/mm²) | Impact Toughness (kg·m/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Hard White Cast Iron | C: 2.8-3.6, Si: 0.3-0.8, Mn: 0.3-0.8, Cr: 1.5-4.5, Ni: 3.0-5.0 | 30-50 | 60-90 | 0.3-0.8 | 50-60 |

| High-Chromium White Cast Iron | C: 2.0-3.0, Si: 0.5-1.5, Mn: 0.5-1.0, Cr: 12-28, Mo: 0.5-3.0 | 40-70 | 70-110 | 0.5-1.0 | 55-65 |

From Table 1, it is evident that both types of white cast iron require significant amounts of alloying elements, which are often scarce in many regions, including China. Moreover, the impact toughness values are still low, limiting their use in applications involving shock loads. Other research efforts have explored adding elements like tungsten or manganese to high-chromium white cast iron, but the performance gains have not substantially exceeded the ranges shown in Table 1. Therefore, alternative methods to enhance the toughness of white cast iron without relying heavily on costly alloys are crucial. In our work, we have investigated two primary approaches: heat treatment for toughening and deformation strengthening, both of which offer promising results for white cast iron.

First, let’s delve into heat treatment toughening. The key idea is to transform the matrix microstructure to improve toughness while maintaining wear resistance. We conducted experiments on white cast iron with a specific composition: C: 2.8-3.2%, Si: 0.6-1.0%, Mn: 0.5-0.8%, Cr: 1.5-2.5%, and Mo: 0.3-0.6%. By employing isothermal quenching processes, we aimed to obtain a bainitic matrix instead of the traditional martensitic or pearlitic structures. Bainite, a microstructure consisting of ferrite and carbide, offers a good balance of strength and toughness. The isothermal transformation can be described using time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagrams, where the kinetics follow the Avrami equation: $$X = 1 – \exp(-kt^n)$$ Here, $X$ is the transformed fraction, $k$ is a rate constant, $t$ is time, and $n$ is an exponent. For white cast iron, controlling the isothermal hold temperature and time allows the carbide network to fragment, isolate, and distribute uniformly within the bainitic matrix. This fragmentation reduces stress concentration sites, enhancing the continuity of the matrix and improving mechanical properties.

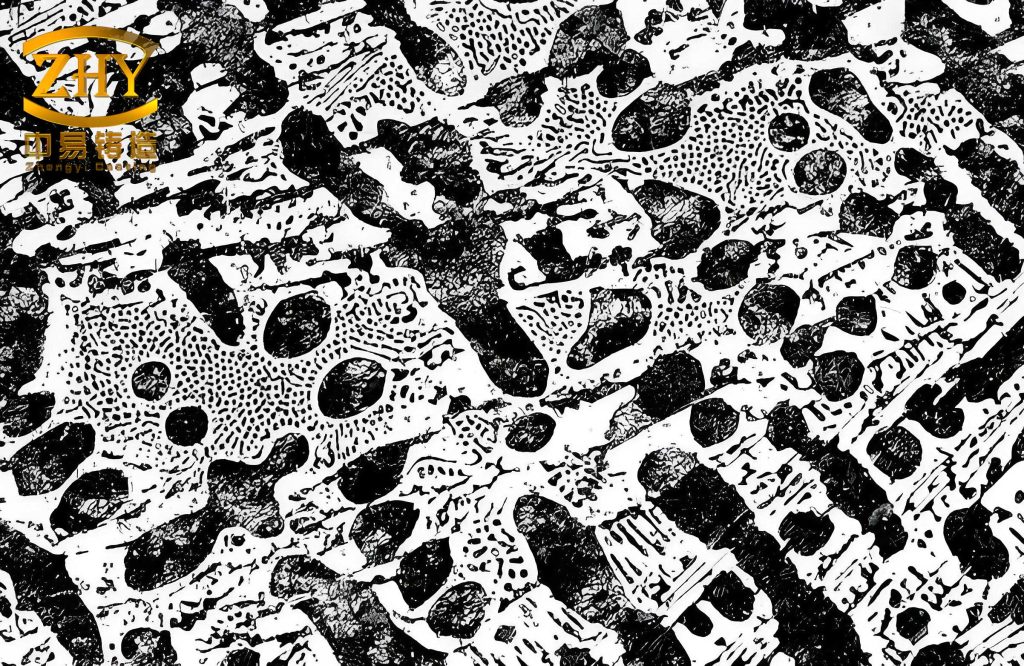

The microstructural changes achieved through heat treatment are pivotal for white cast iron. As shown in the image above, the bainitic white cast iron exhibits a dispersed carbide morphology, which contrasts with the continuous networks in as-cast white cast iron. This improved microstructure leads to superior综合 mechanical properties. For instance, with a composition of C: 3.0%, Si: 0.8%, Mn: 0.7%, Cr: 2.0%, and Mo: 0.5%, we achieved a bending strength of up to 120 kg/mm², an impact toughness of 1.5 kg·m/cm², and a hardness of HRC 55-58. The wear resistance, evaluated using pin-on-disk tests, was found to be 2-3 times higher than that of conventional 65Mn steel. The enhancement in wear resistance can be modeled using Archard’s wear equation: $$V = \frac{K L s}{H}$$ where $V$ is the wear volume, $K$ is a wear coefficient, $L$ is the load, $s$ is the sliding distance, and $H$ is the hardness. In bainitic white cast iron, the increased hardness and toughness reduce $K$, leading to lower wear rates.

To demonstrate the practical benefits of heat-treated white cast iron, we tested several components in industrial applications. The results are summarized in Table 2, highlighting the economic advantages over traditional materials.

| Component Name | Working Conditions | Material Replaced | Improvement in Service Life | Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucket Teeth for Bucket Wheel Excavators | Excavating oil shale and ores | High-Manganese Steel | 2-3 times | 30-40% |

| Grinding Plates for Disc Mill | Grinding various minerals | Chilled Alloy Tool Steel | 1.5-2 times | 20-30% |

| Plowshares for Tractor-Drawn Plows | Plowing different soils | Manganese Plowshare Steel | 2-2.5 times | 25-35% |

| Hammer Pieces for Hammer Crushers | Crushing animal feed | Forged Alloy Steel | 3-4 times | 40-50% |

These results underscore the effectiveness of heat treatment in toughening white cast iron for impact-loaded applications. However, we sought to push the boundaries further by exploring deformation strengthening, or形变强韧化, which involves plastic deformation processes like forging to enhance properties.

Second, we investigated the deformation strengthening of white cast iron. This approach leverages plastic deformation to break down the carbide networks and refine the microstructure, similar to processes used in steels. We used white cast iron with a composition of C: 2.5-3.0%, Si: 0.5-0.9%, Mn: 0.4-0.7%, and Cr: 1.0-2.0%. Specimens were subjected to unidirectional forging (upsetting and drawing) and cross-forging (十字锻拔) at elevated temperatures. The deformation mechanisms can be analyzed using strain hardening models, such as the Hollomon equation: $$\sigma = K \epsilon^n$$ where $\sigma$ is the true stress, $K$ is the strength coefficient, $\epsilon$ is the true strain, and $n$ is the strain-hardening exponent. For white cast iron, deformation induces dislocation networks that interact with carbides, leading to strengthening.

The mechanical properties after unidirectional forging are presented in Table 3. The forging reduction ratio, defined as the percentage reduction in cross-sectional area, plays a critical role in determining the final properties.

| Sample No. | Forging Reduction Ratio (%) | Tensile Strength (kg/mm²) | Bending Strength (kg/mm²) | Impact Toughness (kg·m/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 (As-cast) | 35 | 65 | 0.4 | 58 |

| 2 | 30 | 55 | 95 | 1.2 | 55 |

| 3 | 50 | 70 | 120 | 1.8 | 53 |

| 4 | 70 | 85 | 140 | 2.5 | 50 |

From Table 3, it is clear that deformation significantly enhances the tensile and bending strengths of white cast iron, with improvements of up to 2-3 times compared to the as-cast state. Impact toughness increases dramatically, by 5-6 times, while hardness slightly decreases due to matrix softening but remains high enough for wear resistance. The wear resistance after deformation, tested under abrasive conditions, was found to be 1.5-2 times higher than as-cast white cast iron, attributable to the refined carbide distribution and work hardening.

To further optimize the properties, we applied cross-forging techniques, such as single and double十字锻拔, which involve multi-directional deformation to achieve more homogeneous microstructures. The results are summarized in Table 4.

| Sample No. | Deformation Process | Bending Strength (kg/mm²) | Impact Toughness (kg·m/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) | Tensile Strength (kg/mm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | As-cast | 65 | 0.4 | 58 | 35 |

| B | Single Cross-Forging | 130 | 2.0 | 52 | 75 |

| C | Double Cross-Forging | 150 | 3.0 | 48 | 90 |

| D | Triple Cross-Forging | 160 | 3.5 | 46 | 95 |

The data in Table 4 reveals that cross-forging leads to even better综合 mechanical properties, with impact toughness reaching up to 3.5 kg·m/cm², which is nearly 9 times higher than as-cast white cast iron. This level of toughening is unprecedented for white cast iron and surpasses what can be achieved through alloying alone. The underlying mechanism involves severe plastic deformation that fragments carbides into ultrafine particles and induces grain refinement in the matrix, as described by the Hall-Petch relationship: $$\sigma_y = \sigma_0 + \frac{k_y}{\sqrt{d}}$$ where $\sigma_y$ is the yield strength, $\sigma_0$ is a friction stress, $k_y$ is a constant, and $d$ is the grain size. In deformed white cast iron, the reduced carbide size and refined matrix grains contribute to both strength and toughness.

Combining deformation strengthening with subsequent heat treatment can yield further improvements. For instance, after cross-forging, we applied an isothermal quenching treatment to the white cast iron. This combination resulted in a bainitic matrix with finely dispersed carbides, achieving an impact toughness of 4.0-4.5 kg·m/cm², bending strength of 170-180 kg/mm², and hardness of HRC 50-52. Such properties make this material ideal for components subjected to high冲击 loads, such as crusher hammers or mining equipment. The synergistic effect can be modeled using composite theory, where the overall strength $\sigma_c$ of the white cast iron is given by: $$\sigma_c = V_m \sigma_m + V_{carb} \sigma_{carb}$$ where $V_m$ and $V_{carb}$ are the volume fractions of the matrix and carbides, and $\sigma_m$ and $\sigma_{carb}$ are their respective strengths. Deformation and heat treatment optimize both $V_m$ and $\sigma_m$ by improving matrix continuity and carbide morphology.

In conclusion, the methods we have explored—heat treatment toughening and deformation strengthening—offer viable pathways to enhance the performance of white cast iron without relying on scarce alloying elements. These approaches are particularly suitable for resource-constrained regions like China, where minimizing dependence on imported alloys is economically beneficial. The improvements in impact toughness, strength, and wear resistance are substantial, often exceeding those achieved through traditional alloying. For example, deformation can increase impact toughness by over 10 times compared to as-cast white cast iron, a feat unmatched by other methods. Moreover, the combination of deformation and heat treatment pushes the boundaries further, enabling white cast iron to compete with more ductile materials in demanding applications.

From an industrial perspective, the adoption of these强韧化 techniques can lead to significant cost savings and extended component lifetimes, as evidenced by the case studies in Table 2. Future research could focus on optimizing process parameters, such as deformation temperature, strain rates, and heat treatment cycles, to tailor properties for specific applications. Additionally, numerical modeling using finite element analysis (FEA) could help predict microstructure evolution during deformation, with governing equations like: $$\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = -\nabla \cdot (\mathbf{v} \phi) + S$$ where $\phi$ represents a phase field variable, $\mathbf{v}$ is the velocity field, and $S$ is a source term for phase transformations.

In summary, white cast iron remains a valuable耐磨 material, and through innovative processing routes, its limitations can be overcome. Our work demonstrates that by leveraging heat treatment and deformation, white cast iron can achieve超强韧化, opening new avenues for its use in impact-loaded environments. The potential for widespread application is immense, and we believe these methods hold great promise for the future of white cast iron in industry.