The utilization of white cast iron boasts a long history in industrial applications. Traditional white cast iron, characterized by its pearlitic matrix and plate-like cementite (Fe3C), offers high hardness but suffers from excessive brittleness, limiting its use to components like wheel rims, mill rolls, and certain agricultural tools. The advent of alloyed white cast iron, including high-chromium, low-chromium, and other low-alloy variants, has significantly expanded its application scope. Today, various grades of white cast iron are widely employed as wear-resistant materials in sectors such as metallurgy, mining, cement production, and power generation. Despite these advancements, low toughness and a propensity for brittle fracture remain critical drawbacks, adversely affecting service life. Consequently, enhancing the toughness of white cast iron while maintaining good hardness has become a focal point of research. Numerous modification techniques have been proposed, employing various salts, alloys (containing elements like Mg, Ca, Ba, Sr, and Bi), or composite inoculants incorporating RE, Mg, Ca, and alkali metals to alter carbide morphology and improve properties. While effective, these methods often involve specific, sometimes complex, reagents and procedures tailored to particular white cast iron types. This study aims to explore a more universally applicable, simple, and reliable modification technique for white cast iron.

The core principle of this novel method is to significantly increase the nucleation rate during solidification. This is achieved by introducing a large number of highly dispersed, potent nucleation catalysts into the molten iron. The process involves the simultaneous addition of aluminum and the injection of nitrogen gas. The aluminum reacts with the dissolved nitrogen to form a multitude of aluminum nitride (AlN) particles. These AlN particles, characterized by their high micro-hardness (approximately 1700 HV), high melting point (>2200°C), and stability in iron, act as highly effective heterogeneous nucleation sites. The dramatic increase in nucleation rate effectively restricts the growth of grains and, crucially, the growth and interconnectivity of carbides during the crystallization process. The result is a refined microstructure with improved carbide morphology and distribution, leading to enhanced mechanical properties. Furthermore, part of the nitrogen may adsorb onto the growing surfaces of carbide crystals, forming a thin film that further impedes their growth, contributing to morphological refinement.

The theoretical underpinning can be linked to classical nucleation theory. The nucleation rate, I, is given by:

$$I = I_0 \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta G^*}{kT}\right)$$

where $\Delta G^*$ is the critical free energy for nucleation, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is temperature. By introducing a high density of foreign substrates (AlN) with a low interfacial energy with the solidifying phases, the energy barrier $\Delta G^*$ is significantly reduced, leading to an exponential increase in I. For white cast iron, this promotes the independent, blocky growth of carbides rather than the formation of continuous, brittle networks.

The chemical compositions of the white cast iron types investigated in this study are summarized in Table 1.

| Alloy Type | C | Si | Mn | Cr | Mo | Cu | Ni | P, S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain White Cast Iron | 2.8-3.2 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.5-0.8 | – | – | – | – | <0.1 |

| Low-Cr White Cast Iron | 2.6-3.0 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.5-0.8 | 2.0-3.0 | – | – | – | <0.1 |

| High-Cr White Cast Iron | 2.4-2.8 | 0.6-1.0 | 0.5-0.8 | 14.0-16.0 | 1.0-1.5 | – | – | <0.06 |

| Low-Alloy White Cast Iron | 2.8-3.2 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.3-0.5 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.8-1.2 | <0.06 |

The initial phase of the experimental work focused on determining the optimal processing parameters: the amount of aluminum addition and the duration of nitrogen blowing. An orthogonal experimental design (L9 array) was employed for each type of white cast iron. The initial trial used a baseline of 1 minute of nitrogen blowing and 0.5% Al addition. The factors (Al% and N2 time) were varied across levels to find the combination yielding the best balance of impact toughness and hardness. Castings exhibiting nitrogen porosity or significant shrinkage defects were discarded from the analysis. A preliminary analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the orthogonal test results indicated that the nitrogen blowing time (controlling nitrogen intake) had a more significant influence on impact toughness, while the aluminum addition had a slightly stronger effect on hardness. However, both factors were crucial. Based on these findings, a secondary orthogonal experiment was conducted to refine the parameters. The final optimized parameters established for the experimental conditions were: Aluminum Addition: 0.8% and Nitrogen Blowing Time: 2.5 minutes.

The detailed experimental procedure was as follows. Melting was conducted in a 50 kg capacity acid-lined medium-frequency induction furnace. The molten iron temperature was measured using a Pt-Rh/Pt quick-immersion thermocouple. When the temperature reached 1480±10°C, the iron was tapped into a preheated ladle. Pre-heated aluminum blocks (size ~20×20 mm) were placed at the bottom of the ladle prior to tapping. After tapping, the molten bath was stirred once manually. Subsequently, nitrogen gas at a controlled pressure (approximately 0.2 MPa) was introduced into the melt through a porous plug located at the bottom of the ladle (schematic shown conceptually below). The blowing time was precisely controlled with a stopwatch. Upon completion of nitrogen injection, the melt was stirred once more before pouring. All test bars (for impact and wear tests) were cast in dry sand molds.

Mechanical testing included impact toughness measurement on a 150 J Charpy impact tester and hardness measurement on a Rockwell hardness tester (HRC scale). Abrasive wear tests were conducted using a standard sand abrasion apparatus with quartz sand as the abrasive media. The results for the various white cast iron types, treated with the optimized Al-N modification parameters, are consolidated in Table 2.

| White Cast Iron Type | Condition | Impact Toughness, ak (J/cm²) | Hardness, HRC | Relative Wear Loss (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain White Cast Iron | As-Cast | 6.8 | 52 | 100 (Baseline) |

| Heat Treated** | 8.5 | 55 | 82 | |

| Low-Cr White Cast Iron | As-Cast | 8.2 | 56 | 91 |

| Heat Treated | 10.5 | 58 | 75 | |

| High-Cr White Cast Iron | As-Cast | 12.5 | 58 | 85 |

| Heat Treated | 16.8 | 62 | 68 | |

| Low-Alloy White Cast Iron | As-Cast | 10.0 | 54 | 88 |

| Heat Treated | 13.2 | 57 | 72 |

* Wear loss normalized to as-cast plain white cast iron. Lower percentage indicates better wear resistance.

** Heat treatment typically involved austenitizing followed by air cooling or tempering, depending on alloy type.

The results clearly demonstrate that the aluminum-nitrogen modification treatment significantly improves the impact toughness of all types of white cast iron, with a concurrent increase in hardness. This synergistic improvement is attributed to the combined effect of carbide morphology modification and matrix strengthening.

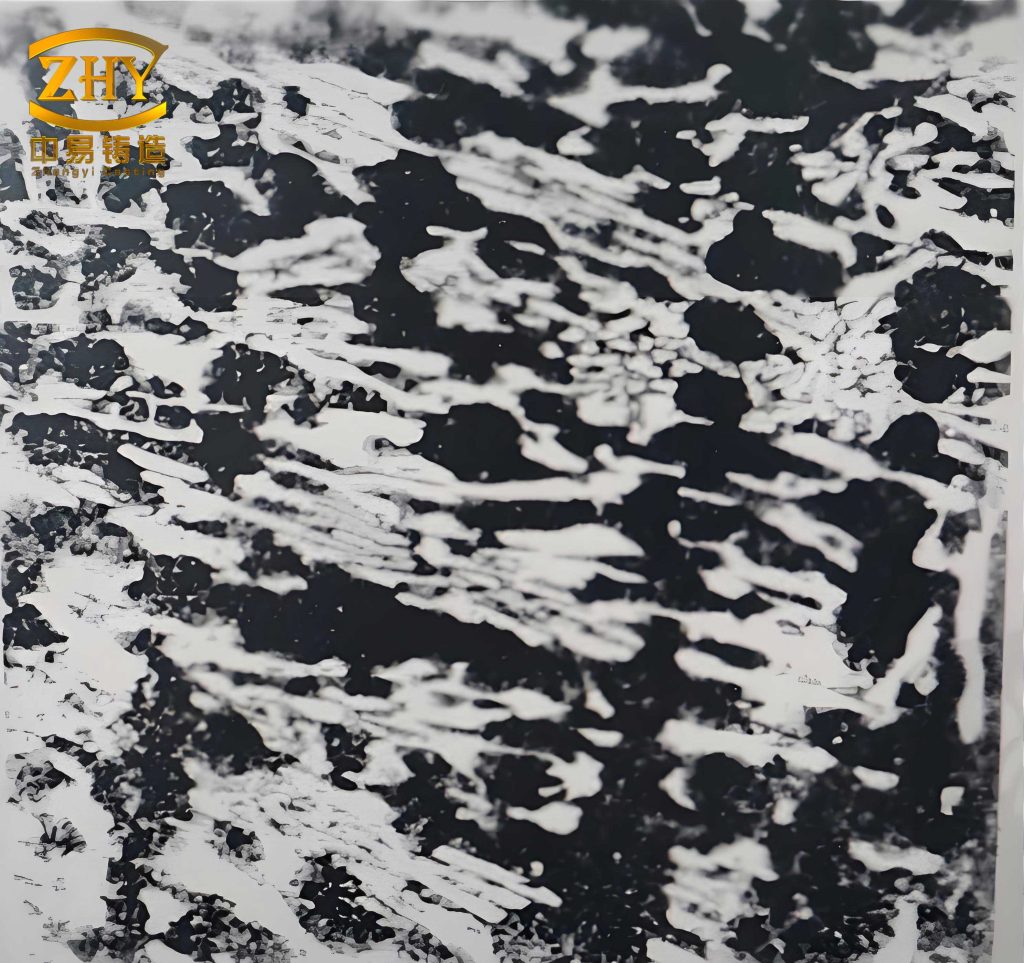

Metallographic examination revealed a profound change in carbide morphology. In the modified white cast iron, the carbides appeared as isolated, blocky, or granular particles. The continuous, interconnected carbide network typically observed in unmodified plain or low-alloy white cast iron was effectively broken up. This microstructural change is the primary reason for the enhanced toughness. The mechanism is effective across different white cast iron types because, although high-chromium white iron solidifies with a more isolated, eutectic carbide structure under normal conditions, the principle of increasing nucleation rate to control grain and carbide growth remains universally applicable. The key difference lies in the starting morphology, but the refinement and further isolation/rounding effect provided by the abundant AlN nuclei are beneficial in all cases.

The role of nitrogen is particularly interesting. While gases like hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are generally considered detrimental, controlled nitrogen addition can be beneficial. The solubility of nitrogen in molten iron is approximately 0.04%, while typical cast iron contains only 0.005-0.015% N, mostly in the form of nitrides of Si, Mn, Al, etc. Porosity due to nitrogen is generally reported only when the content exceeds about 0.13%. In this process, the nitrogen content is carefully increased to around 0.08-0.10%—high enough to create a substantial population of nitrides but below the threshold for gas defect formation. The reaction governing AlN formation can be considered:

$$[Al] + [N] \rightleftharpoons AlN_{(s)}$$

with a very negative free energy change, making it highly favorable. The equilibrium and final nitrogen content can be related to the partial pressure of nitrogen gas, $P_{N_2}$, and the aluminum activity, $a_{Al}$, by an equation of the form:

$$K = \frac{1}{a_{Al} \cdot [N]}$$

where [N] is the dissolved nitrogen content in equilibrium with AlN. By controlling the blowing time (gas volume) and Al addition, the process seeks to maximize the product [Al]·[N] to precipitate a fine dispersion of AlN.

The efficacy of this treatment is further enhanced when combined with subsequent heat treatment. The initial break-up of the carbide network facilitates the dissolution and spheroidization of sharp carbide edges during high-temperature austenitization, accelerating the isolation and globularization of carbides. This explains the further improvement in comprehensive properties observed in the heat-treated condition for all modified white cast iron samples.

A production trial was conducted at a foundry producing sand brick molds using low-chromium white cast iron. The application of the aluminum-nitrogen modification process resulted in a marked improvement in the product’s comprehensive mechanical properties. The service life of the modified low-chromium white cast iron molds increased by approximately 40% compared to traditional carburized steel molds used for the same purpose. This not only extended component life but also reduced manufacturing costs by saving on machining time and material expenses. A comparison is shown in Table 3.

| Mold Material | Treatment | Production Cost (per pair) | Service Life (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Cr White Cast Iron | Unmodified | Base Cost | ~300 |

| Low-Cr White Cast Iron | Modified (Al-N) | Base Cost + Mod. | ~420 |

| Carburized Steel (0.2% C) | Carburizing | Higher (Material + Machining + Treatment) | ~300 |

In conclusion, the aluminum addition and nitrogen blowing modification technique presents a distinctive and effective approach for enhancing the properties of white cast iron. Its fundamental strength lies in creating a high density of highly dispersed, potent nucleation catalysts (AlN), leading to a significant increase in nucleation rate. This effectively controls grain and carbide growth during solidification, resulting in refined microstructures with improved, non-continuous carbide morphologies. The method has demonstrated applicability across a broad spectrum of white cast iron types, including plain, low-chromium, high-chromium, and low-alloy white cast iron, improving both toughness and hardness. The process is relatively simple, reliable, and suitable for industrial application. Subsequent heat treatment further augments the property improvements. While the role of nitrogen in microalloying and matrix strengthening in steels is well-known, its specific contribution to strengthening the matrix in various white cast iron systems treated by this method warrants further detailed investigation to fully elucidate the synergistic mechanisms at play.