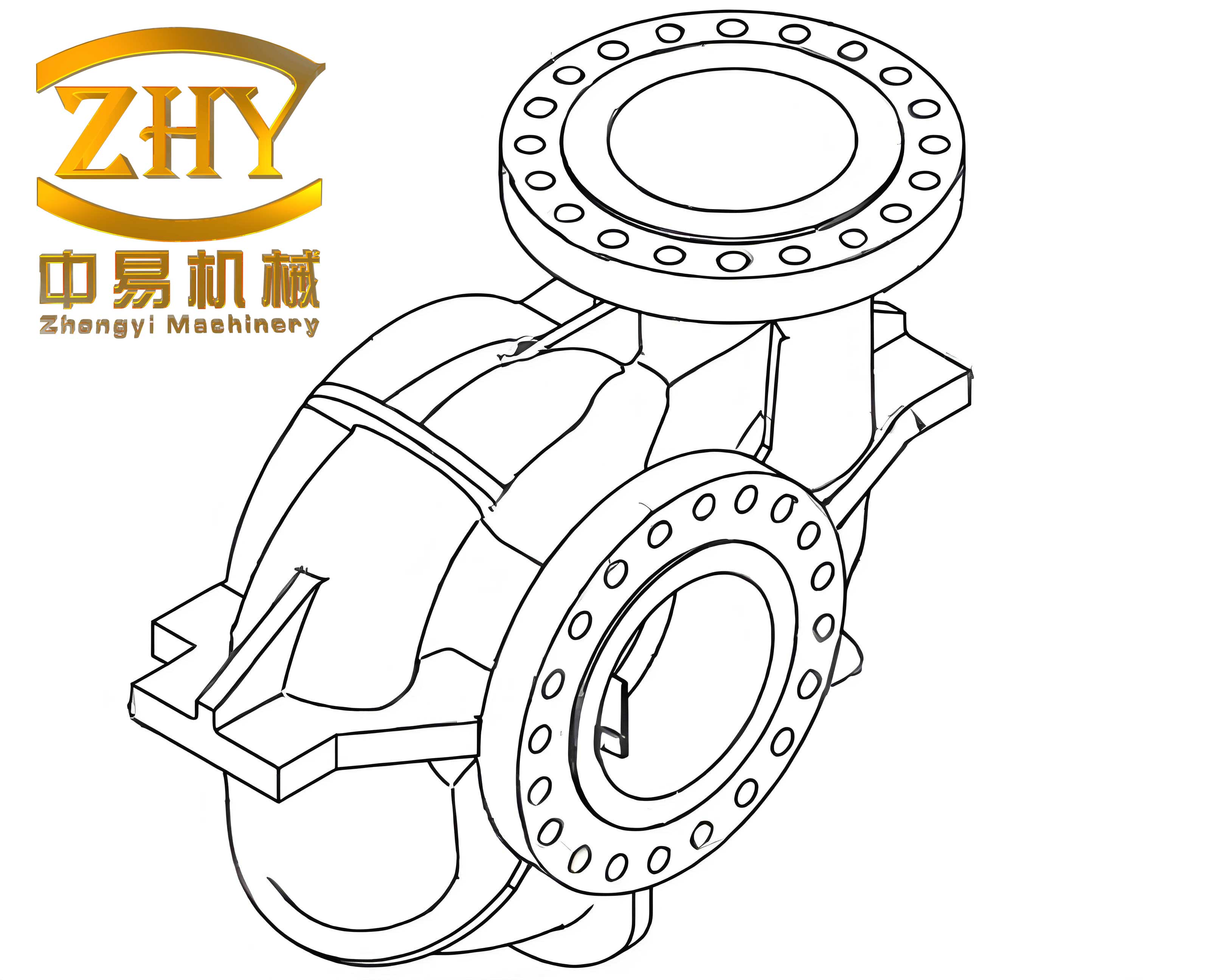

In my research, I focused on overcoming the challenges associated with manufacturing high-integrity shell castings for aerospace applications, specifically a volute casing component used in large-scale rocket engines. Shell castings, particularly those made from high-performance alloys like K4169, are critical due to their operation under extreme temperatures and pressures. The volute’s complex geometry, featuring a spiral flow passage and significant wall thickness variations, makes it prone to defects such as shrinkage porosity during solidification. This article details my systematic approach to developing a reliable investment casting process for these demanding shell castings.

The core material was a K4169 alloy, a high-strength iron-nickel based superalloy. Its composition is pivotal for achieving the necessary mechanical properties. I have summarized the key chemical constituents in the table below.

| Element | Content | Element | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0.054 | Co | 0.050 |

| Ni | 52.78 | Cr | 19.09 |

| Mo | 3.09 | Al | 0.47 |

| Ti | 0.95 | B | 0.0026 |

| Zr | 0.025 | Nb | 5.07 |

| Cu | 0.0012 | Si | 0.087 |

| Mn | 0.0042 | Fe | Balance |

My first major challenge was forming the intricate internal spiral cavity of the shell castings. Traditional metal cores were impractical for extraction. I opted for a soluble core approach using urea. This choice was driven by its ease of manufacture, rapid dissolution post-molding, and excellent surface finish capability. The urea cores were pressed and meticulously inspected for defects before being assembled into the wax mold assembly. The success of this step is fundamental for the accuracy of the final shell castings.

Wax pattern fabrication is another critical step influencing the dimensional precision of shell castings. To mitigate shrinkage and sinking in the thick flange sections, I employed a secondary forming technique using pre-pressed cold wax blocks. This “false core” method effectively reduces the effective wall thickness during primary wax injection, controlling contraction. The wax injection parameters were optimized as follows: wax temperature at 60°C, injection pressure of 2.5 MPa, injection time of 60 s, and a hold time of 60 s. The linear shrinkage of the wax pattern, a key variable, can be estimated by:

$$ \epsilon_w = \beta_w \cdot \Delta T_w $$

where $\epsilon_w$ is the wax linear strain, $\beta_w$ is the coefficient of thermal contraction for the wax blend, and $\Delta T_w$ is the temperature drop from injection to room temperature. Using cold wax inserts helped minimize $\epsilon_w$ in critical areas, resulting in a high-quality, dimensionally accurate overall wax pattern for the shell castings.

The next phase involved building the ceramic mold, or shell, that would define the external geometry of the metal shell castings. I utilized a silica sol binder system for its good colloidal stability and high-temperature strength. The shell was built with multiple layers: a primary interface layer and several backup reinforcement layers. The details of the shell-building sequence are captured in the following table.

| Layer | Binder | Refractory Flour | Stucco Material | Grit Size | Drying Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st & 2nd (Face Coat) | Silica Sol | Zircon Flour (325 mesh) | Alumina Sand | 100 mesh | 24h, 23±2°C, 50±5% RH |

| 3rd to 7th/8th (Backup Coat) | Silica Sol | Chamotte Flour | Chamotte Sand | 40-60 to 16-24 mesh | 12-24h per layer, 23±2°C, <60% RH |

Special attention was paid to the narrow inlet of the spiral passage during shell building. Extended drying times and careful removal of loose stucco grains were necessary to ensure shell integrity in these recessed areas, which is crucial for defect-free shell castings. The final shell mold, after dewaxing and firing, provided a robust negative of the desired component.

The design of the gating and feeding system is paramount for the quality of shell castings. My objective was to ensure smooth filling and directional solidification to feed shrinkage. I designed a bottom-gating system with multiple ingates positioned at the thick sections of the flanges. A large pour cup was incorporated to quickly establish metallostatic pressure. To scientifically evaluate this design, I conducted numerical simulation using ProCAST software. The governing equations for fluid flow and heat transfer during mold filling and solidification are based on the Navier-Stokes and energy equations. For incompressible flow during filling:

$$ \nabla \cdot \vec{v} = 0 $$

$$ \rho \left( \frac{\partial \vec{v}}{\partial t} + \vec{v} \cdot \nabla \vec{v} \right) = -\nabla p + \mu \nabla^2 \vec{v} + \rho \vec{g} $$

where $\vec{v}$ is velocity, $p$ is pressure, $\rho$ is density, $\mu$ is dynamic viscosity, and $\vec{g}$ is gravity. The energy equation including phase change is:

$$ \rho C_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} + \rho C_p \vec{v} \cdot \nabla T = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) – \rho L \frac{\partial f_s}{\partial t} $$

where $T$ is temperature, $C_p$ is specific heat, $k$ is thermal conductivity, $L$ is latent heat, and $f_s$ is solid fraction.

The simulation results confirmed the efficacy of my design. The filling sequence showed a stable, progressive upward movement of the metal front, minimizing turbulence. The solidification simulation revealed that the thin spiral section solidified first, followed by the thicker flanges, with the feeders remaining liquid longest to provide feeding. A parameter summarizing the thermal gradient (G) and solidification rate (R) is critical for predicting microstructure and defects in shell castings. The thermal gradient at the solid-liquid interface can be expressed as:

$$ G = \left| \frac{dT}{dx} \right|_{interface} $$

A high G/R ratio is generally desirable to promote columnar growth and reduce shrinkage porosity.

To optimize the pouring parameters, I simulated nine combinations of pouring temperature ($T_p$) and mold preheat temperature ($T_m$). The goal was to minimize the predicted fraction of microporosity ($V_{por}$), which can be empirically related to local solidification time ($t_f$) and pressure ($P$):

$$ V_{por} \propto \frac{1}{P \cdot (t_f)^n} $$

where $n$ is a material constant. The simulation outcomes indicated that the combination of $T_p = 1450°C$ and $T_m = 850°C$ offered the best compromise, reducing the propensity for microshrinkage while maintaining a manageable total solidification time. This optimization is essential for producing sound shell castings.

| Case | Pouring Temp., $T_p$ (°C) | Mold Temp., $T_m$ (°C) | Filling Time (s) | Total Solidification Time (s) | Relative Microporosity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1420 | 800 | ~2.65 | ~52 | 0.85 |

| 2 | 1420 | 850 | ~2.63 | ~58 | 0.78 |

| 3 | 1420 | 900 | ~2.60 | ~65 | 0.82 |

| 4 | 1450 | 800 | ~2.61 | ~56 | 0.72 |

| 5 | 1450 | 850 | ~2.61 | ~60 | 0.68 |

| 6 | 1450 | 900 | ~2.59 | ~68 | 0.75 |

| 7 | 1480 | 800 | ~2.58 | ~61 | 0.74 |

| 8 | 1480 | 850 | ~2.57 | ~72 | 0.80 |

| 9 | 1480 | 900 | ~2.56 | ~80 | 0.88 |

Guided by this analysis, I proceeded with the final casting trials using the optimized parameters. The alloy was double-melted—first into a master alloy and then remelted in a vacuum induction furnace for pouring. The resulting shell castings were heat treated, cleaned, and subjected to rigorous non-destructive testing. The volute shell castings exhibited excellent surface quality, particularly in the complex spiral passage. Fluorescent penetrant and X-ray inspections confirmed the absence of major defects like cracks or gross porosity, meeting the stringent specification requirements for aerospace shell castings.

Metallographic examination of sections from the flanges and flow passage revealed a sound microstructure with no significant microporosity, assessed to be below Level 1 according to relevant standards. The mechanical properties of test bars cast alongside the shell castings met the target specifications, with stress rupture life exceeding 100 hours at 650°C under 620 MPa stress. This confirms the robustness of the developed process for high-performance shell castings.

In reflection, the integration of soluble core technology, advanced wax pattern techniques, a tailored ceramic shell system, and simulation-driven gating design proved to be a successful strategy. The process highlights several general principles for complex shell castings: the importance of managing thermal gradients, the value of numerical simulation in optimizing parameters like $T_p$ and $T_m$, and the need for a holistic approach from pattern to heat treatment. Future work could explore further refinement of the shell ceramic composition to enhance thermal shock resistance or investigate the use of different core materials for even more intricate shell castings. The knowledge gained reinforces the capability of investment casting to produce near-net-shape, high-integrity shell castings for the most demanding applications.