In my extensive experience within the foundry industry, addressing defects such as porosity in casting has been a central challenge, particularly for high-integrity components like stainless steel castings. The pursuit of perfection in cast components drives continuous innovation in process technologies. This article consolidates practical knowledge and technical analyses focused on understanding and mitigating porosity in casting, drawing from real-world applications in shell baking and complex integral casting production. The manifestation of porosity in casting can vary from superficial pits to deep-seated blowholes that compromise structural integrity, making its prevention paramount.

The foundational step for many precision casting processes, especially the investment casting of stainless steel, is the proper baking or sintering of the ceramic shell mold. An improperly baked shell is a primary contributor to subsequent porosity in casting. Traditionally, coal was used for heating, but environmental and efficiency concerns necessitated a shift. Through firsthand implementation, I have evaluated a system utilizing light diesel oil in a specially designed combustion furnace. This furnace features insulated walls and roof, with preheated air atomizing and injecting fuel for combustion. The key advantages are rapid ignition, fast heating, uniform temperature distribution, and significant fuel savings. The reduction in thermal loss ensures the shell is baked thoroughly and consistently, which directly minimizes one source of gas generation that leads to porosity in casting during metal pouring.

A typical thermal cycle can reach 1000°C within half an hour. While the initial cycle consumes more fuel, subsequent cycles average only 15–17 kg of diesel per batch for a standard-sized furnace. The complete and uniform baking of the shell, regardless of its geometric complexity, ensures better mold strength and reduced gas evolution during metal fill. This results in a dramatic improvement in casting soundness, with yield rates for defect-free castings, particularly those free from porosity in casting, reaching up to 98%. The furnace design allows for both automatic and manual control, maintaining stable high-temperature zones. Importantly, combustion is nearly complete after the initial phase, eliminating smoke and environmental pollution. This approach underscores that controlling the mold-making thermal process is a critical first defense against porosity in casting.

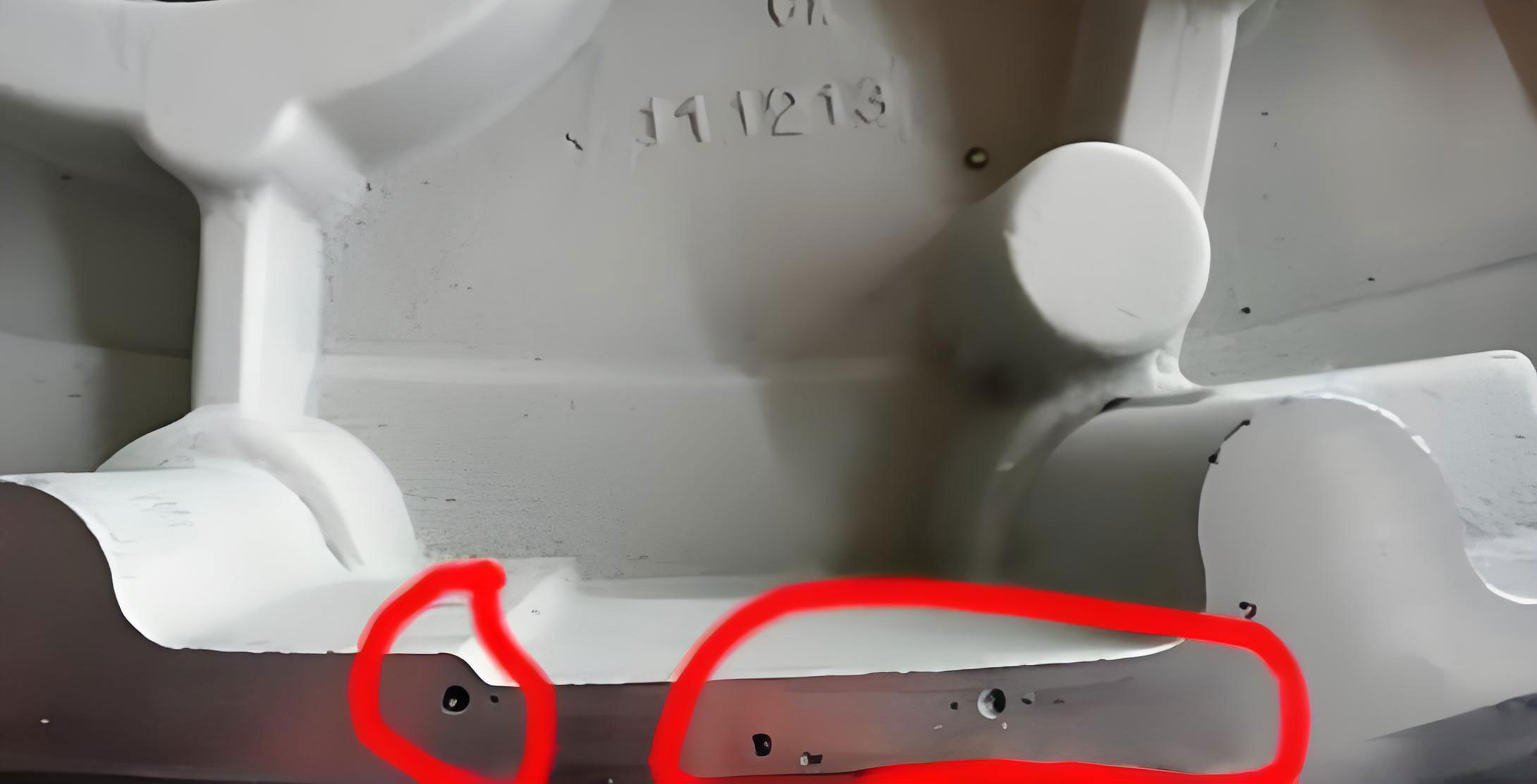

However, even with a perfectly baked shell, porosity in casting can originate from the core-making and molding assembly processes for larger, intricate castings like integral stainless steel turbine runners. These components, often made from low-carbon, high-chromium martensitic stainless steels (e.g., ZG06Cr13Ni4Mo), are highly prone to oxidation and gas absorption due to their chemical activity. The common defects are blowholes (gas porosity) and cold shuts (oxide film entrapment), both severe forms of discontinuity that can be classified under the broader category of porosity in casting.

To analyze the root causes, let’s first examine the typical chemical composition of these stainless steels, which influences their gas solubility and oxidation behavior.

| Grade | C (%) max | Si (%) | Mn (%) max | P (%) max | S (%) max | Ni (%) | Cr (%) | Mo (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZG06Cr13Ni4Mo | 0.06 | 0.4-1.0 | 1.0 | 0.035 | 0.030 | 3.5-5.0 | 11.5-13.5 | 0.4-1.0 |

| ZG06Cr13Ni5Mo | 0.06 | 0.4-1.0 | 1.0 | 0.035 | 0.030 | 4.5-5.5 | 11.5-13.5 | 0.4-1.0 |

| ZG06Cr13Ni6Mo | 0.06 | 0.4-1.0 | 1.0 | 0.035 | 0.030 | 5.0-6.5 | 11.5-13.5 | 0.4-1.0 |

The low carbon and high chromium content make the melt susceptible to forming oxide films and absorbing hydrogen, which later precipitates as porosity in casting. The casting geometry—a central hub with multiple thin, curved buckets—exacerbates the problem. The buckets act like capillaries, slowing metal flow and increasing surface area for heat loss and gas interaction.

The genesis of blowhole-type porosity in casting in these runners is often linked to moisture in the mold assembly. In a standard process, large core assemblies are bonded and backed with sand. If drying is incomplete, residual moisture turns to steam during pouring. The pressure build-up from this steam in confined spaces can force gas into the solidifying metal. The fundamental condition for gas entrapment leading to porosity in casting can be expressed as:

$$ P_{steam} > P_{metal} + \frac{2\gamma}{r} $$

Where \( P_{steam} \) is the steam pressure within the mold cavity, \( P_{metal} \) is the metallostatic pressure from the liquid metal head, \( \gamma \) is the surface tension of the liquid metal, and \( r \) is the effective pore radius. When this inequality holds, steam penetrates the liquid metal, forming bubbles that become porosity in casting upon solidification.

In practice, I have found that a two-stage oven drying protocol for all cores and assembled molds is highly effective. The process sequence is: Core manufacture → First oven drying → Coating application → Core assembly and sand backing → Second oven drying → Final mold closure → Pouring. This ensures virtually complete moisture removal, driving down \( P_{steam} \) and preventing this source of porosity in casting. Furthermore, controlling the time between mold extraction from the oven and pouring is critical to maintain an optimal mold temperature, which influences metal flow and gas behavior.

Cold shuts, another defect related to poor surface fusion, are essentially oxidized film entrapments. They appear as horizontal lines on the bucket surfaces. Their formation is tied to slow metal front advancement and excessive cooling in thin sections, allowing a stable oxide film to form on the liquid surface. When the metal flow pressure is insufficient to break this film, the film gets folded into the casting, creating a seam. This defect is intrinsically linked to conditions that promote other forms of porosity in casting, as both are favored by low metal temperature and high oxide content. The tendency for film formation can be related to the melt oxidation kinetics and thermal conditions. The temperature drop \( \Delta T \) in a thin section can be approximated by:

$$ \Delta T \approx \frac{(T_{pour} – T_{mold}) \cdot A \cdot t}{\rho \cdot V \cdot c_p} $$

Where \( T_{pour} \) is pouring temperature, \( T_{mold} \) is mold temperature, \( A \) is surface area, \( t \) is time, \( \rho \) is density, \( V \) is volume, and \( c_p \) is specific heat. For thin-walled buckets, the high \( A/V \) ratio causes rapid cooling (\( \Delta T \) is large), promoting oxide film stability and the risk of cold shuts—a planar type of discontinuity often found alongside micro-porosity in casting.

Therefore, the dual strategy to prevent both gas porosity and cold shuts (thereby minimizing all forms of porosity in casting) involves: 1) Eliminating mold gases by thorough drying, and 2) Elevating mold temperature to slow metal cooling. Data from production trials clearly show the impact. The following table summarizes key process parameters and their effect on defect rates for integral runner castings:

| Process Parameter | Original Method | Optimized Method | Effect on Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core/Mold Drying | Single stage + torch drying | Two-stage oven drying | Steam pressure (\(P_{steam}\)) drastically reduced, eliminating blowholes. |

| Mold Temp at Pour | Ambient to ~50°C | Controlled at 80-120°C | Slower metal cooling, higher metal fluidity, reduced oxide film strength. |

| Pouring Temperature | ~1570-1590°C (after hold) | ~1580-1600°C (after hold) | Improved ability to fuse metal fronts and dissolve gases. |

| Defect Incidence | High (blowholes & cold shuts) | Very Low (near zero) | Porosity in casting effectively eliminated. |

The interplay between these factors is complex. For instance, the solubility of hydrogen in stainless steel, a major contributor to gas porosity in casting, decreases sharply upon solidification. The equilibrium hydrogen content \( C_H \) is given by Sieverts’ law:

$$ C_H = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}} $$

where \( K_H \) is the temperature-dependent solubility constant. During cooling, if the local hydrogen concentration exceeds solubility, it precipitates as molecular \( H_2 \), forming porosity in casting. Proper mold drying minimizes \( P_{H_2} \) from decomposing moisture, while faster solidification from a cold mold can trap more hydrogen, exacerbating porosity in casting.

In summary, my journey in tackling casting defects has solidified a holistic philosophy. Preventing porosity in casting is not a single-step fix but a system-wide control strategy. It begins with the mold shell itself—using efficient, controlled baking to create a stable, low-gas evolution foundation. For complex core assemblies, it extends to rigorous thermal management of all mold components to eliminate moisture and control heat absorption. The mathematical relationships governing gas pressure, metal fluidity, and heat transfer provide a framework for diagnosing issues. Every variable—from fuel type in shell furnaces to the minute an oven-dried mold is poured—impacts the final soundness. By viewing the process through the lens of controlling the sources and drivers of porosity in casting, foundries can achieve remarkably high yields of flawless castings, even in demanding applications like stainless steel hydro turbine runners. The continuous battle against porosity in casting is won through meticulous attention to thermal and gaseous dynamics at every stage of the molding and pouring process.

Further considerations involve the metallurgical aspects. The choice of stainless steel grade affects its solidification mode and susceptibility to shrinkage porosity, which often interacts with gas porosity in casting. Inoculation practices and precise control of pouring temperature and speed are also vital. Advanced simulation software can now model mold filling and solidification, predicting hotspots where porosity in casting is likely to occur, allowing for pre-emptive design of feeders and chills. However, the fundamental physical principles remain. The pressure balance equation for gas invasion, the kinetics of oxide film formation, and the heat extraction equations form the trinity of analysis for porosity in casting. Future advancements may focus on real-time monitoring of mold atmosphere and metal temperature to dynamically adjust pouring parameters, closing the loop on defect prevention. For now, the proven methods of thorough drying, controlled preheating, and optimized furnace design for shell baking stand as robust, effective defenses in the relentless effort to eradicate porosity in casting from high-performance metal components.