The transition from high-pressure die casting to metal mold (permanent mold) casting for complex, integrity-critical components represents a significant engineering challenge, particularly for automotive shell castings where pressure tightness is a non-negotiable requirement. This article delves into the comprehensive process analysis and innovative mold design required to successfully produce a demanding aluminum shell casting, focusing on the methodologies to eliminate shrinkage porosity and gas defects that plague conventional high-pressure techniques.

The core challenge with many thin-walled yet locally thick shell castings in high-pressure die casting (HPDC) stems from the inherent characteristics of the process. While excellent for high-volume production of complex, thin geometries, HPDC involves extremely high filling velocities and rapid cooling under intense pressure. For sections with significant variation in wall thickness, this can lead to two primary, interrelated defects:

- Shrinkage Porosity: In thicker sections, the rapid solidification of the outer skin can trap liquid metal in isolated pools. Subsequent shrinkage during solidification creates internal voids or porosity clusters. This is catastrophic for the pressure tightness of shell castings designed to contain fluids or gases.

- Gas Entrapment: The turbulent filling at high speeds inevitably traps air and lubricant vapors within the melt. These gases become compressed during the intensification phase but often remain as fine, subsurface pores. When the casting’s surface is machined, these pores are exposed, leading to leak paths or cosmetic failures.

A comparative analysis of the two processes for this specific class of components is essential:

| Process Parameter | High-Pressure Die Casting (HPDC) | Metal Mold Casting (Gravity/Permanent Mold) |

|---|---|---|

| Filling Velocity | Very High (20-100 m/s) | Low to Moderate (Gravity-fed) |

| Solidification Pressure | Very High (500-1000+ bar) | Atmospheric (1 bar) + Metallostatic Head |

| Cooling Rate | Extremely High | Controlled, Directional |

| Primary Defect Risk for Thick Sections | Shrinkage Porosity, Gas Porosity | Shrinkage (manageable with risers) |

| Machinability of Subsurface | Poor (risk of exposing gas pores) | Excellent (denser structure) |

| Suitability for Pressure-Tight Shell Castings | Limited, often requires impregnation | Excellent, inherent integrity |

The decision to employ metal mold casting hinges on the ability to control solidification and feeding. The thermal dynamics of a solidifying casting in a metal mold can be approximated by Chvorinov’s rule for solidification time, $t$, of a simple shape:

$$ t = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where $V$ is volume, $A$ is surface area, $n$ is a constant (often ~2), and $B$ is a mold constant dependent on mold material, superheat, and interface conditions. For a successful casting, the solidification sequence must be directed toward the feeding sources (risers). This requires designing the thermal system (mold geometry, cooling channels, coatings) such that the thermal modulus $(V/A)$ increases along the path to the riser. For a complex shell casting with a thick flange, this means ensuring the flange solidifies last.

Process Engineering for the Shell Casting

The part in question is a mid-sized aluminum A356 (Al-Si7Mg) shell casting with a primary functional requirement of maintaining a leak-tight seal at 0.6 MPa. The initial failure in HPDC, manifesting as both leakage and subsurface gas porosity upon machining, directly points to the shortcomings outlined above. The metal mold process was selected to fundamentally alter the solidification and feeding paradigm.

Gating and Feeding Strategy: A bottom-gating system with a serpentine runner was adopted. This design minimizes turbulence and oxide formation during filling. The governing equation for the flow rate $Q$ in a gravity-fed system is derived from Bernoulli’s principle:

$$ Q = A_g \cdot v = A_g \cdot \sqrt{2gH} $$

where $A_g$ is the choke (ingate) area, $v$ is flow velocity, $g$ is gravity, and $H$ is the effective metallostatic head. A carefully calculated $A_g$ ensures a non-turbulent fill velocity, typically below 0.5 m/s for aluminum in permanent molds, to prevent air entrainment.

A key feature is the placement of a slag trap/drain just before the ingate. This acts as a buoyancy-based filter where oxides and first-filled, cooler metal are trapped, preventing them from entering the casting cavity. Crucially, this chamber also functions as a blind riser, providing liquid metal feed to the adjacent casting section during solidification. The feeding efficiency of a riser can be modeled by the required volume $V_r$:

$$ V_r \geq \frac{V_c \cdot \alpha}{(1 – \alpha) \cdot \eta} $$

where $V_c$ is the volume of the region being fed, $\alpha$ is the volumetric shrinkage of the alloy (~6% for A356), and $\eta$ is the feeding efficiency factor (less than 1 due to premature freezing of the riser neck).

Orientation and Thermal Management: The casting is oriented with its large, critical sealing plane facing downward. This achieves two goals: 1) It places this surface in a region of highest pressure and earliest solidification, promoting density, and 2) It establishes a “thick-over-thin” progression. The thickest section of the shell casting (a small boss or flange) is positioned at the top. At this location, an open top riser is placed. This riser remains exposed to atmosphere, allowing for visual monitoring of fill and providing the highest possible feeding pressure from the full metallostatic head. Its efficiency is higher than that of a blind riser as it is not air-locked.

Venting is paramount. Unlike HPDC, which relies on massive pressure to force gas into solution, metal mold casting requires its positive expulsion. Venting is achieved through:

- Precision parting line vents (typically 0.10-0.15 mm deep).

- Strategic use of permeable vent plugs in deep cavity areas. The gas flow through these vents, driven by the pressure of expanding air and vapor, is critical for preventing back-pressure.

Innovative Mold Structural Design

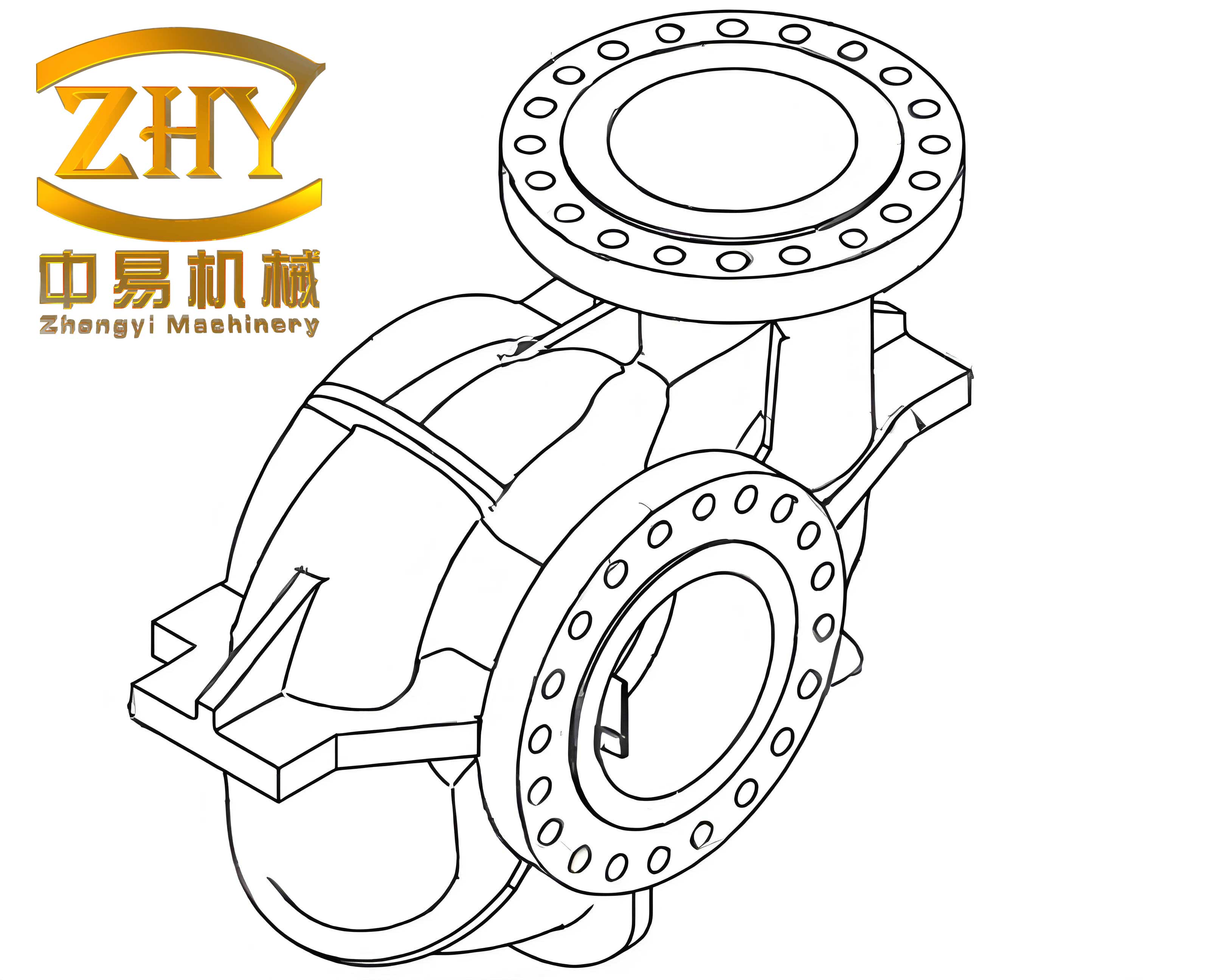

The design of the metal mold must facilitate the defined process strategy while ensuring reliability, part quality, and ease of operation. The mold consists of two main assemblies: the outer metal mold and the core box for producing the complex internal sand cores.

1. Outer Metal Mold Assembly

The mold is designed to operate on a standard vertical-parting permanent mold machine. The primary structural challenge was an undercut feature inside the cavity. Instead of employing a complex internal slide mechanism (which would be costly and a potential failure point), an innovative “loose block” solution was implemented.

Loose Block Mechanism: A precisely machined block forms the undercut geometry. This block is placed into the lower mold section (the drag or bottom plate) manually or via a simple automation sequence before the core is set. After casting and solidification, during mold opening, this block remains with the casting on the ejector side. It is then removed laterally or lifted out with the casting. This elegant solution prioritizes mold simplicity and reliability over fully automated complexity, a key consideration for robust production of shell castings.

Ejection System Design: A critical aspect for cosmetic and functional integrity is ejector pin placement. The ejection force $F_e$ required is a function of the casting’s shrinkage onto cores and mold walls:

$$ F_e = \mu \cdot P_c \cdot A_c $$

where $\mu$ is the coefficient of friction, $P_c$ is the contraction pressure from thermal shrinkage, and $A_c$ is the contact area. Incorrect pin placement can distort the casting or mar critical surfaces. Pins were strategically located on the large downward-facing plane (a non-cosmetic, machined surface) and other non-critical areas. Unlike conventional designs where one half is stationary, this setup features two moving mold halves. The casting settles onto the bottom plate (which contains the loose block), and a bottom-mounted ejection system pushes the casting upward for removal. This minimizes relative movement between the casting and the delicate loose block during the initial opening phase.

Precision Alignment: To withstand thermal cycling and maintain parting line integrity, the mold uses long, tapered guide pins and a “dike-style”封闭式 (enclosed perimeter) locating structure. This ensures co-planarity of the parting surfaces under thermal expansion, preventing flash and ensuring dimensional consistency for the shell castings.

2. Hot Box Core Mold Design

The internal cavity of the shell casting is formed by a resin-bonded sand core, produced using the hot box process for strength and accuracy. The core box is a two-cavity design for productivity.

Gassing and Venting: Each cavity has an independent sand shooting inlet, ensuring uniform sand packing and density in both cores. Deep recesses in the core are vented using permeable metal inserts (venting plugs) to allow the curing gases and air to escape during the amine catalyst blow, preventing core voids or soft spots. Additional venting channels are machined along the parting line.

Dual Ejection System: To ensure reliable release of the complex, potentially sticky cured cores, a dual-side ejection system is employed. Ejector pins are arranged on both the core box drag and cope sides, synchronized to push the core off both surfaces simultaneously, preventing distortion or breakage. Spring-loaded return pins ensure the ejector plates reset cleanly for the next cycle.

| Parameter | Value / Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Alloy | A356 (AlSi7Mg0.3) | Excellent castability, response to heat treatment, good strength. |

| Pouring Temperature | ~720 °C | Sufficient superheat for fluidity, minimizes gas pickup and shrinkage. |

| Mold Temperature | 200 – 300 °C (Pre-heated & maintained) | Prevents mistruns, controls solidification rate, reduces thermal shock. |

| Mold Coat (Die Coat) | Ceramic-based, thin insulating layer. | Prevents soldering, controls heat transfer, aids part release. |

| Core Sand | Silica sand with phenolic resin (Hot Box) | High strength, good surface finish, dimensional accuracy. |

| Cycle Time (Estimated) | 2 – 4 minutes | Dependent on wall thickness and cooling design. |

Performance Outcome and Technical Advantages

The implementation of the metal mold casting process resulted in a decisive resolution of the quality issues. The produced shell castings underwent standard pressure tightness testing. The results demonstrated a significant performance leap:

- Pressure Tightness: The castings consistently withstood test pressures exceeding 0.8 MPa, well above the specified 0.6 MPa requirement. This confirms the effective elimination of interconnected shrinkage and gas porosity networks.

- Machinability: Subsequent machining of the large lower plane revealed a dense, homogeneous microstructure free from subsurface gas blisters or pores, validating the effectiveness of the tranquil filling and effective venting strategy.

The success of this project underscores several key engineering principles for manufacturing integrity-critical shell castings:

- Process Selection Over Force: Metal mold casting uses controlled, directional solidification aided by gravity feeding to achieve soundness, as opposed to HPDC which attempts to “compress” defects under immense pressure—a strategy that often fails for varying sections.

- Thermal Gradient Management: Strategic orientation and riser placement create a predictable thermal gradient, ensuring that the last points to solidify are always fed by liquid metal. This is governed by the fundamental heat transfer equation:

$$ \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) = \rho C_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} $$

where $k$ is thermal conductivity, $T$ is temperature, $\rho$ is density, and $C_p$ is specific heat. The mold design manipulates the boundary conditions to solve this equation favorably. - Defect Prevention at Source: Bottom gating with a slag trap prevents oxide entrainment, while extensive venting eliminates back-pressure from gases. This proactive approach is more reliable than post-cast impregnation or salvage.

- Simplified Tooling for Complexity: The use of a manually placed loose block for an internal undercut demonstrates that not every geometric feature requires a complex actuated slide. This reduces cost, maintenance, and potential failure modes in the production of complex shell castings.

In conclusion, for automotive and other high-reliability applications where pressure integrity and structural soundness are paramount, metal mold casting presents a superior alternative to high-pressure die casting for certain classes of components. The design transition requires a deep understanding of solidification science, fluid dynamics, and inventive but practical tooling design. By prioritizing controlled feeding and defect prevention over sheer speed and pressure, it is possible to produce shell castings that meet and exceed stringent performance specifications, particularly for parts with challenging geometry and demanding functional requirements like pressure retention.