In the field of industrial wear-resistant materials, white cast iron alloys, particularly those alloyed with chromium, stand as a cornerstone for applications involving severe abrasion. The inherent hardness derived from their carbide networks provides excellent resistance to cutting and gouging. However, the very feature that grants this hardness—the brittle carbides and often hard matrix—can be a liability under dynamic or impact loading, leading to premature failure through spalling or catastrophic fracture. This duality presents a fundamental challenge in materials engineering: optimizing the often-inverse relationship between hardness (resistance to penetration) and toughness (resistance to crack propagation). While extensive research has mapped the wear resistance of white cast iron under sliding or low-stress abrasion, the interplay between its fracture toughness and performance under impact-abrasive conditions—a common scenario in mining, mineral processing, and milling—remains less comprehensively charted. This work delves into this interplay, investigating how the matrix microstructure of a low-chromium white cast iron, tailored through heat treatment, dictates its fracture toughness and how this toughness, in concert with hardness, governs wear mechanisms and material loss under distinct impact energies.

The essence of abrasive wear, especially when coupled with impact, transcends simple material removal by cutting. It is a process of cumulative damage. Hard abrasive particles, under applied load, indent the surface. Upon subsequent tangential motion (sliding or rolling), these particles can plow through the material, creating grooves (cutting), or they can cause repeated plastic deformation of the subsurface layers. This cyclic deformation leads to strain accumulation, nucleation of subsurface cracks, and ultimately, the detachment of material flakes—a mechanism known as fatigue spalling or delamination. The resistance to crack initiation and, more critically, to crack propagation is therefore paramount. The plane-strain fracture toughness, denoted as $K_{IC}$, serves as a fundamental material property quantifying this resistance to catastrophic crack extension under tensile stress. In the context of wear, a higher $K_{IC}$ implies a greater ability to absorb energy from propagating cracks before they link up and cause large-scale spallation. Consequently, for components facing impact-abrasion, an exclusive focus on maximizing hardness can be detrimental if it catastrophically reduces $K_{IC}$. The optimal material is one that achieves a site-specific synergy between these two properties.

Previous studies on high-chromium white cast iron have revealed the existence of an optimal range for $K_{IC}$ that maximizes wear resistance under certain sliding abrasion conditions, demonstrating that both excessively high and low toughness can be suboptimal. However, these findings are largely rooted in quasi-static or low-strain-rate wear tests. The introduction of significant kinetic energy via impact fundamentally alters the stress state, strain rates, and dominant damage mechanisms on the material’s surface. This research aims to bridge this knowledge gap by systematically examining a series of low-chromium white cast iron samples with varied matrix structures. By correlating their mechanically measured $K_{IC}$ values with their performance in a controlled impact-abrasion test at two distinct energy levels, we seek to construct a mechanistic map. This map will illustrate how the dominance shifts between cutting-controlled and deformation-controlled wear regimes as a function of impact energy, and how the material’s hardness and toughness dictate its ranking within each regime.

I. Experimental Methodology: Material, Processing, and Characterization

The foundation of this study is a low-chromium white cast iron, chosen for its relevance in cost-sensitive, high-wear applications. The alloy was melted in a medium-frequency induction furnace. To refine the carbide morphology and improve overall toughness, a rare-earth silicon ferroalloy inoculant was added during tapping into the ladle, with an addition amount of 0.15 wt.%. The final chemical composition of the cast material, verified by optical emission spectrometry, is given in Table 1. The carbon and chromium contents are strategically balanced to form predominantly (Fe,Cr)3C-type eutectic carbides, which provide a good compromise between abrasion resistance and fracture toughness compared to the harder but more brittle M7C3 carbides prevalent in high-chromium alloys.

| C | Si | Mn | Cr | P | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 4.5 | <0.05 | <0.03 | Bal. |

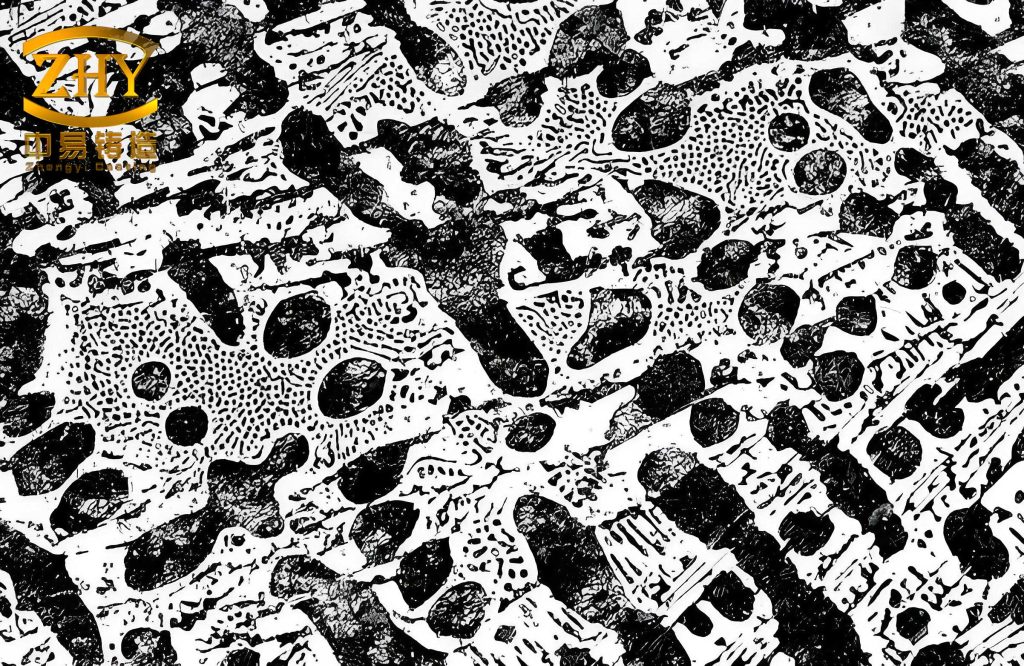

Image analysis of polished samples revealed a carbide volume fraction of approximately 28% $\pm$ 2%. The as-cast blanks were machined into pre-forms for fracture toughness specimens. These specimens were then subjected to five different heat treatment cycles designed to produce a wide spectrum of matrix microstructures and, consequently, hardness and toughness. The specific austenitizing temperatures, quenching media, tempering, and isothermal treatments were selected to generate matrices ranging from a high-hardness, low-toughness martensitic structure to softer, more ductile structures of lower bainite, pearlite, and even tempered martensite. The detailed heat treatment parameters and the resulting macro/micro-hardness values are summarized in Table 2. Macro-hardness was measured using a Rockwell C scale tester, while the matrix micro-hardness (avoiding carbides) was determined using a Vickers indenter under a 50 gf load.

| Sample ID | Heat Treatment Process | Macro-Hardness (HRC) | Matrix Micro-Hardness (HV0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 950°C austenitize, air cool (as-cast normalized) | 52 | 510 |

| B | 880°C austenitize, 280°C salt bath quench & isothermally transform | 58 | 680 |

| C | 880°C austenitize, 360°C salt bath quench & isothermally transform | 55 | 620 |

| D | 880°C austenitize, oil quench, 250°C temper | 61 | 750 |

| E | 880°C austenitize, oil quench, 450°C temper | 56 | 580 |

Fracture Toughness Testing: The plane-strain fracture toughness ($K_{IC}$) was evaluated using single-edge notched bend (SENB) specimens in a three-point bending configuration. The specimens, with final dimensions of 10 mm x 20 mm x 100 mm and a surface finish better than Ra 0.8 μm, were pre-cracked using a wire-electro discharge machine (EDM) to introduce a sharp notch, followed by fatigue pre-cracking to generate a natural crack tip. Testing was conducted on a servo-hydraulic universal testing machine at a slow crosshead speed, strictly following the guidelines of the ASTM E399 standard for valid $K_{IC}$ determination. The critical stress-intensity factor was calculated using the standard formula:

$$K_{IC} = \frac{P_Q S}{B W^{3/2}} \cdot f\left(\frac{a}{W}\right)$$

where $P_Q$ is the load corresponding to a specified crack extension offset, $S$ is the support span, $B$ is the specimen thickness, $W$ is the specimen width, $a$ is the crack length, and $f(a/W)$ is the dimensionless geometry calibration factor.

Impact-Abrasive Wear Testing: Wear performance was assessed using a dynamic impact-abrasive wear tester. The upper specimens (test material) were extracted via wire-EDM directly from the broken halves of the fracture toughness specimens, ensuring perfect microstructure correspondence. The counterface lower specimens were made from hardened and tempered GCr15 bearing steel (equivalent to SAE 52100). The test involved the upper specimen undergoing a prescribed number of impacts per minute against the lower rotating disc, with a controlled flow of abrasive particles entrained at the contact interface. The key test parameters were:

- Abrasive: 40-70 mesh quartz sand (SiO2).

- Abrasive feed rate: 250 g/min.

- Rotational speed of lower disc: 200 rpm.

- Impact frequency: 100 impacts per minute.

- Impact Energies: 2.0 J and 4.5 J (Two separate test series).

- Total test duration: 5000 impact cycles after a 500-cycle run-in period at 1.0 J.

The wear resistance, $\varepsilon$, is defined as the inverse of the mass loss: $\varepsilon = 1 / \Delta m$. Mass loss was measured using an analytical balance with a precision of 0.1 mg, and each reported value is the average from two identical tests.

II. Results: Quantitative Relationships between Properties

The measured fracture toughness ($K_{IC}$) and impact-abrasive wear resistance ($\varepsilon$) for all five variants of low-chromium white cast iron under the two impact energies are consolidated in Table 3.

| Sample ID | $K_{IC}$ (MPa√m) | Mass Loss $\Delta m_{2.0J}$ (g) | Wear Resistance $\varepsilon_{2.0J}$ (g⁻¹) | Mass Loss $\Delta m_{4.5J}$ (g) | Wear Resistance $\varepsilon_{4.5J}$ (g⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 18.5 | 0.245 | 4.08 | 0.198 | 5.05 |

| B | 14.2 | 0.198 | 5.05 | 0.235 | 4.26 |

| C | 16.8 | 0.215 | 4.65 | 0.205 | 4.88 |

| D | 12.1 | 0.175 | 5.71 | 0.268 | 3.73 |

| E | 17.9 | 0.228 | 4.39 | 0.189 | 5.29 |

1. Fracture Toughness vs. Matrix Micro-Hardness:

A clear and strong inverse correlation is observed between the matrix micro-hardness ($H_m$) and the fracture toughness ($K_{IC}$). As the matrix is hardened—through formation of martensite or fine lower bainite—its ability to blunt cracks and undergo plastic deformation at the crack tip diminishes, leading to a reduction in $K_{IC}$. The data fits a linear relationship with high confidence, described by:

$$K_{IC} = \alpha – \beta \cdot H_m$$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are positive material constants. For this specific low-chromium white cast iron, the empirical fit yields:

$$K_{IC} (MPa\sqrt{m}) \approx 32.5 – 0.027 \cdot H_m (HV_{0.05}) \quad (R^2 = 0.94)$$

This equation succinctly captures the inherent trade-off engineered through heat treatment: increasing the matrix hardness by 100 HV leads to an approximate decrease of 2.7 MPa√m in fracture toughness.

2. Impact-Abrasive Wear Resistance vs. Matrix Hardness:

The influence of matrix hardness on wear resistance is not absolute; it is critically dependent on the applied impact energy. This dependency reveals a fundamental shift in the dominant wear mechanism.

- At Lower Impact Energy (2.0 J): Wear resistance increases monotonically with increasing matrix hardness. The relationship is best described by a power-law function:

$$\varepsilon_{2.0J} \propto (H_m)^\gamma$$

where $\gamma > 0$. The harder matrix more effectively resists the penetration and cutting action of the abrasive particles, leading to shallower grooves and less material removal per impact cycle. - At Higher Impact Energy (4.5 J): The trend reverses. Wear resistance now decreases with increasing matrix hardness, following an approximately linear decay:

$$\varepsilon_{4.5J} \approx \delta – \eta \cdot H_m$$

where $\delta$ and $\eta$ are constants. The high-strain-energy impacts overwhelm the material’s ability to resist deformation purely by hardness. The associated low toughness of the hard matrix becomes a liability, promoting crack propagation and large-scale spallation.

3. Impact-Abrasive Wear Resistance vs. Fracture Toughness:

Mirroring the above, the role of fracture toughness is also dualistic and energy-dependent.

- At 2.0 J Impact Energy: A higher $K_{IC}$ correlates with lower wear resistance. The relationship can be modeled as:

$$\varepsilon_{2.0J} \propto (K_{IC})^{-\lambda}$$

with $\lambda > 0$. In this regime, toughness is not the primary requirement. Instead, the relatively softer, tougher matrices associated with higher $K_{IC}$ are less resistant to micro-cutting and micro-plowing, leading to higher material loss. - At 4.5 J Impact Energy: The correlation inverts. Wear resistance increases significantly with increasing fracture toughness, following an exponential-like trend:

$$\varepsilon_{4.5J} \propto \exp(\kappa \cdot K_{IC})$$

where $\kappa$ is a positive constant. Here, the material’s capacity to absorb energy from impact without allowing cracks to propagate and link up is the dominant factor controlling material loss. High $K_{IC}$ effectively suppresses the spalling mechanism.

This clear inversion underscores that there is no universally “best” value for $K_{IC}$ or hardness. The optimal combination is a direct function of the service conditions, specifically the impact severity.

III. Discussion: Deconstructing the Wear Mechanism Transition

The observed reversal in the trends linking material properties to wear performance can only be explained by a transition in the fundamental micromechanisms of material removal. Under impact-abrasion, an abrasive particle can cause damage through two primary sequential actions: (1) Normal Indentation/Impact creating a crater and inducing subsurface plastic strain, and (2) Tangential Traversal leading to either cutting or further plastic deformation (plowing).

At the lower impact energy (2.0 J), the kinetic energy of the abrasive particles is insufficient to cause massive plastic flow or deep indentation in the harder phases. The dominant material removal mechanism is micro-cutting and micro-fracture. The sharp quartz particles act like miniature cutting tools. In this scenario, the primary role of the metallic matrix is to support the hard carbides and resist being easily gouged out. A harder matrix provides better support, reducing the depth and width of the cut grooves. The wear scars are characterized by numerous, relatively shallow parallel grooves and evidence of carbide fracture and dislodgment. Fracture toughness plays a minor role because the scale of cracking is limited to individual carbides or immediate matrix regions; large, coalescing cracks do not have enough driving force to form.

At the higher impact energy (4.5 J), the story changes dramatically. Each impact imparts sufficient energy to cause significant plastic deformation of the matrix and even bending or fracture of carbide networks. The dominant mechanism shifts to low-cycle fatigue and spalling (delamination). The tangential motion following impact now causes severe plowing and pile-up of heavily deformed material. With repeated impacts, this deformed subsurface layer undergoes cyclic strain hardening, leading to the nucleation of subsurface cracks, typically at carbide/matrix interfaces or at the boundaries of heavily deformed zones. These cracks propagate and eventually link up parallel to the surface, resulting in the detachment of thin, flake-like wear debris. In this regime, the matrix’s hardness alone is inadequate. A hard but brittle matrix (low $K_{IC}$) offers little resistance to crack propagation. Once a crack initiates, it spreads rapidly, leading to large spalls. Conversely, a tougher matrix (higher $K_{IC}$), even if softer, can effectively blunt and arrest these cracks, dramatically reducing the volume of material removed per spalling event. The wear surface in this case shows evidence of large, irregular pits, plastic smearing, and severely deformed plateaus, with less prominent cutting grooves.

This mechanistic interpretation aligns perfectly with the property correlations. At low energy, where cutting dominates, wear resistance $\varepsilon$ is primarily a function of hardness $H$. We can propose a simplified model:

$$\varepsilon_{cutting} \approx C_1 \cdot H^n$$

where $C_1$ is a constant and $n \approx 1-2$. At high energy, where deformation-fatigue dominates, wear resistance becomes a strong function of fracture toughness $K_{IC}$, perhaps moderated by hardness:

$$\varepsilon_{spalling} \approx C_2 \cdot \frac{K_{IC}^m}{H^p}$$

where $C_2$, $m$, and $p$ are constants, with $m$ being significantly positive and $p$ being small or positive (as excessive softness could accelerate initial deformation). The transition between these two wear regimes occurs at a critical impact energy $E_c$, which itself is likely a function of the material’s $H/K_{IC}$ ratio:

$$E_c \propto \left( \frac{H}{K_{IC}^2} \right)$$

Materials with a high hardness-to-toughness-squared ratio will transition to spalling-dominated wear at lower impact energies.

| Impact Energy Regime | Dominant Wear Mechanism | Key Controlling Property | Wear Resistance Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., 2.0 J) | Micro-cutting, Micro-plowing, Carbide Fracture | Matrix & Bulk Hardness ($H$) | $\varepsilon \uparrow$ as $H \uparrow$ and $K_{IC} \downarrow$ |

| High (e.g., 4.5 J) | Plastic Deformation, Low-Cycle Fatigue, Spalling/Delamination | Fracture Toughness ($K_{IC}$) | $\varepsilon \uparrow$ as $K_{IC} \uparrow$ and $H \downarrow$ |

The implications for the design and selection of low-chromium white cast iron and other white cast iron grades are profound. For applications involving mainly sliding abrasion or very low-energy impacts (e.g., slurry pumps handling fine particles), maximizing hardness through a fully martensitic matrix is the correct path. However, for components like impactor bars in crushers, hammer tips, or lifter bars in semi-autogenous grinding (SAG) mills, where impacts are severe, sacrificing some hardness to gain substantial fracture toughness—via an isothermally transformed lower bainitic matrix or a suitably tempered martensite—will yield superior service life. The data suggests that for the studied low-chromium white cast iron under high-impact conditions, a $K_{IC}$ value in the range of 17-19 MPa√m, corresponding to a matrix hardness of 580-620 HV, provided the best balance, as seen in samples C and E.

IV. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This investigation into the impact-abrasive wear behavior of heat-treated low-chromium white cast iron provides a clear, quantitative framework for understanding the critical interplay between matrix hardness and fracture toughness. The principal conclusions are:

- The fracture toughness ($K_{IC}$) of low-chromium white cast iron exhibits a strong inverse linear relationship with its matrix micro-hardness, governed by the equation $K_{IC} \approx 32.5 – 0.027 \cdot H_m$.

- The influence of these mechanical properties on wear resistance is not intrinsic but is decisively governed by the impact energy, which selects the dominant wear mechanism.

- Under low-impact energy (2.0 J), wear proceeds primarily via micro-cutting. In this regime, wear resistance increases with increasing matrix hardness and, conversely, decreases with increasing fracture toughness.

- Under high-impact energy (4.5 J), wear proceeds primarily via plastic deformation and fatigue spalling. In this regime, wear resistance increases with increasing fracture toughness and, conversely, decreases with increasing matrix hardness.

- Therefore, material selection and heat treatment optimization for white cast iron components must be based on a thorough assessment of the operational impact severity. A single-minded pursuit of maximum hardness is detrimental for high-impact applications.

Future research should expand on this foundational work by:

- Investigating a broader range of impact energies to more precisely map the transition energy $E_c$ for different white cast iron microstructures.

- Incorporating other white cast iron families, such as high-chromium white cast iron with M7C3 carbides or nickel-chromium white cast irons, to develop a more universal mechanism-property map.

- Utilizing advanced in-situ monitoring or post-mortem cross-sectional analysis (e.g., using Focused Ion Beam-SEM) to quantitatively measure subsurface deformation depth and crack density, linking them directly to the measured $K_{IC}$ and wear rate.

- Developing constitutive or finite element models that integrate hardness, toughness, and impact parameters to predict wear life, moving beyond empirical correlations towards predictive design.

In summary, the performance of white cast iron under impact-abrasion is a classic embodiment of a materials optimization problem. This study provides the empirical evidence and mechanistic understanding necessary to navigate the hardness-toughness landscape, ensuring that the selected grade of white cast iron is not just hard, but intelligently tough for its specific duty.