In my research, I focus on improving the properties of white cast iron, specifically medium manganese white cast iron, which is known for its high hardness but poor toughness due to the presence of carbide networks. The goal is to modify the microstructure through various processes to enhance strength and ductility, making it more suitable for industrial applications. White cast iron has traditionally been considered brittle and unsuitable for forging, but my work challenges this notion by demonstrating that with proper treatment, it can exhibit significant plastic deformation at high temperatures.

The inherent brittleness of white cast iron stems from its ledeburite structure, where carbides form a continuous network that embrittles the material. This limits its use in applications requiring impact resistance. To address this, I employed a combination of modification treatments, thermoplastic deformation, and heat treatment to alter the morphology and distribution of carbides. By doing so, I aimed to transform the carbide network into isolated or semi-continuous forms, thereby improving the mechanical properties. White cast iron, when alloyed with medium manganese, shows promise due to its balance of cost and performance.

In this study, I used a medium manganese white cast iron with a specific chemical composition, as summarized in Table 1. The alloy was melted in a medium-frequency induction furnace and cast into specimens for further processing. The emphasis was on exploring the forgeability and subsequent property enhancement of white cast iron, which has been largely unexplored in prior literature.

| C | Si | Mn | S | P | Cr | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.41 | 1.10 | 5.03 | 0.042 | 0.06 | — | — |

The experimental methods included modification treatment, forging, and heat treatment. For the modification, I added inoculants to the molten white cast iron to refine the as-cast structure. The forgeability tests involved upsetting and drawing specimens at high temperatures, followed by various heat treatment cycles. The forging process was conducted at temperatures around 1000–1100°C, with deformation degrees ranging from 30% to 50%. The relationship between deformation degree and mechanical properties can be expressed using a simple empirical formula for strength enhancement:

$$ \sigma_{bb} = \sigma_0 + k \cdot \varepsilon^n $$

where $\sigma_{bb}$ is the bending strength, $\sigma_0$ is the base strength of as-cast white cast iron, $k$ is a material constant, $\varepsilon$ is the deformation strain, and $n$ is an exponent typically between 0.5 and 1.0 for white cast iron. This formula helps quantify the effect of plastic deformation on property improvement.

I conducted impact and bending tests to evaluate toughness and strength, respectively. The results showed that white cast iron exhibited remarkable high-temperature plasticity, allowing it to be forged without cracking. This was a key finding, as it contradicts the traditional view that white cast iron is inherently non-forgeable due to its carbide network. The microstructure evolution during forging was critical: at high temperatures, the austenite matrix deforms plastically, causing the carbide networks to fracture and align along the deformation direction. This process effectively breaks up the continuous carbide structure, leading to a more homogeneous distribution.

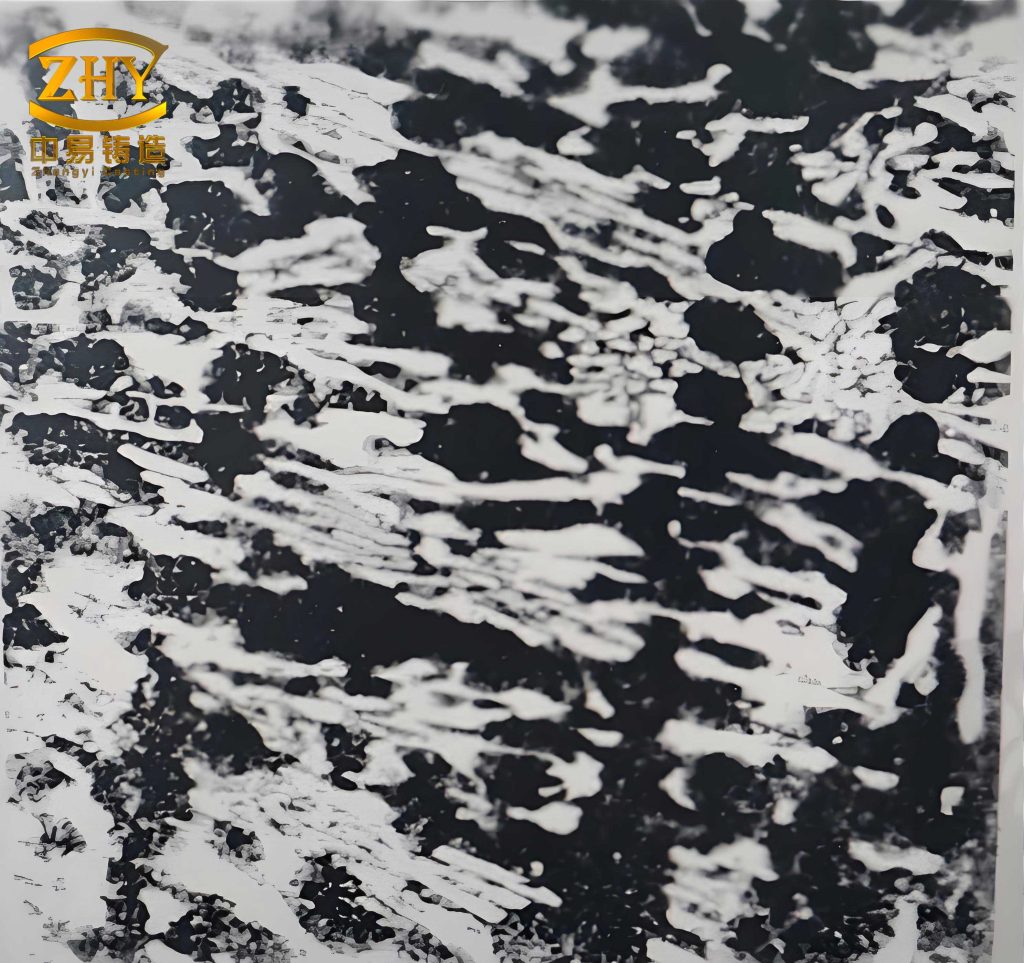

The microstructural changes in white cast iron were analyzed using metallographic techniques. In the as-cast state, the white cast iron displayed a typical ledeburitic structure with carbide networks surrounding the primary phases. After deformation, these networks were disrupted, transitioning from a continuous mesh to semi-network, streaky, or blocky forms. For instance, at 30% deformation, the carbide network began to elongate, and at 50% deformation, it was largely fragmented into fine particles. This refinement is crucial for enhancing the toughness of white cast iron, as it reduces stress concentration points.

To quantify the mechanical property improvements, I compiled data from various tests, as shown in Table 2. The bending strength and impact toughness increased significantly with higher deformation degrees, while hardness remained relatively stable. This indicates that the modifications primarily affect the carbide morphology without altering the overall carbon content, which governs hardness in white cast iron.

| Condition | Bending Strength, $\sigma_{bb}$ (MPa) | Impact Toughness, $\alpha_K$ (J/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| As-cast white cast iron | 303 | 3.13 | 42.7 |

| 30% deformation | 612 | 6.40 | 41 |

| 40% deformation | 654 | 8.90 | 43 |

| 50% deformation | 720 | 12.60 | 45 |

The enhancement in properties can be attributed to several factors. First, the plastic deformation refines the microstructure by breaking down coarse carbides and eliminating casting defects such as porosity. Second, the deformation introduces dislocations and other defects that strengthen the matrix. In white cast iron, this is particularly important because the austenite matrix can work-harden during forging. The relationship between dislocation density and strength can be modeled using the Taylor equation:

$$ \Delta \sigma = \alpha G b \sqrt{\rho} $$

where $\Delta \sigma$ is the increase in yield strength, $\alpha$ is a constant, $G$ is the shear modulus, $b$ is the Burgers vector, and $\rho$ is the dislocation density. For white cast iron, this contributes to the overall strength gain after deformation.

Heat treatment further optimized the properties of the forged white cast iron. I applied processes like direct quenching after forging, conventional quenching, and austempering. The results, summarized in Table 3, show that austempering provided the best combination of strength and toughness. This is due to the formation of bainite, martensite, and retained austenite, which improve impact resistance. The microstructure after austempering revealed needle-like bainite alongside carbides, enhancing the ductility of white cast iron.

| Heat Treatment Process | Bending Strength, $\sigma_{bb}$ (MPa) | Impact Toughness, $\alpha_K$ (J/cm²) | Hardness (HRC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional quench and temper | 840 | 14.3 | 52 |

| Direct quench after forging and temper | 1199.3 | 17.4 | 54 |

| Austempering | 1101.7 | 20.7 | 51.5 |

The improvement from heat treatment can be explained by phase transformations. In white cast iron, the matrix undergoes changes from pearlite to harder phases. For example, during austempering, the cooling rate controls the formation of bainite, which has a good balance of strength and toughness. The kinetics of this transformation can be described using the Avrami equation:

$$ f = 1 – \exp(-k t^n) $$

where $f$ is the fraction transformed, $k$ is a rate constant, $t$ is time, and $n$ is an exponent. For white cast iron, this helps in optimizing the heat treatment parameters to achieve desired microstructures.

Another key aspect is the role of modification treatment prior to forging. By adding inoculants, I refined the as-cast structure of white cast iron, which made subsequent deformation more effective. The inoculants promote heterogeneous nucleation, reducing the carbide size and improving uniformity. This is critical for white cast iron because finer carbides are less detrimental to toughness. The effect of inoculation on carbide size can be quantified using the Hall-Petch relationship for strength:

$$ \sigma_y = \sigma_0 + \frac{k_y}{\sqrt{d}} $$

where $\sigma_y$ is the yield strength, $\sigma_0$ is the friction stress, $k_y$ is a constant, and $d$ is the carbide diameter. In white cast iron, smaller carbides lead to higher strength and better toughness.

Throughout this research, I emphasized the importance of high-temperature plasticity in white cast iron. Contrary to common belief, my experiments showed that white cast iron with carbon content below 3.0% can be forged successfully. This is because at elevated temperatures, the austenite matrix becomes highly ductile, allowing it to deform and carry the brittle carbides. The carbide hardness also decreases at high temperatures, as supported by literature, making deformation easier. For instance, at 1225 K, carbides in white cast iron have a hardness of only 170 HV, compared to much higher values at room temperature.

To further analyze the deformation behavior, I considered the stress-strain relationship during forging. For white cast iron, the flow stress can be modeled using a power-law equation:

$$ \sigma = K \varepsilon^m $$

where $\sigma$ is the flow stress, $K$ is a strength coefficient, $\varepsilon$ is the strain, and $m$ is the strain-rate sensitivity. In my tests, white cast iron exhibited a positive $m$ value at high temperatures, indicating good formability. This is essential for industrial forging processes involving white cast iron.

The microstructural evolution during deformation was also studied in detail. As deformation degree increased, the carbide networks in white cast iron transitioned from continuous to fragmented forms. At 50% deformation, the carbides appeared as fine streaks or blocks, uniformly distributed in the matrix. This homogenization reduces stress concentrations and improves crack resistance. The change in carbide morphology can be correlated with the Zener-Hollomon parameter, which combines temperature and strain rate effects:

$$ Z = \dot{\varepsilon} \exp\left(\frac{Q}{RT}\right) $$

where $Z$ is the Zener-Hollomon parameter, $\dot{\varepsilon}$ is the strain rate, $Q$ is the activation energy, $R$ is the gas constant, and $T$ is the absolute temperature. For white cast iron, a higher $Z$ value leads to finer carbides after deformation.

In addition to mechanical tests, I performed wear resistance evaluations on the modified white cast iron. Although not detailed in the initial content, wear properties are crucial for applications like mining and machinery. The refined carbide structure in white cast iron after modification and forging should improve wear resistance by providing hard particles in a tough matrix. This aligns with the general principle that white cast iron is often used for abrasive environments.

The combination of modification, forging, and heat treatment offers a comprehensive approach to enhancing white cast iron. By integrating these processes, I achieved a bending strength of over 1100 MPa and an impact toughness of 20.7 J/cm² in medium manganese white cast iron. These values represent significant improvements over conventional white cast iron, opening up new possibilities for its use in structural components.

From a theoretical perspective, the modifications in white cast iron can be understood through solidification and deformation mechanics. The initial as-cast structure is governed by eutectic reactions, leading to carbide networks. By applying plastic deformation, I introduced shear forces that break these networks. Subsequent heat treatment then optimizes the matrix phase. This holistic approach is key to unlocking the potential of white cast iron as a versatile material.

In conclusion, my research demonstrates that medium manganese white cast iron can be effectively modified through a sequence of processes. The key findings include its forgeability at high temperatures, the refinement of carbide morphology, and the substantial improvement in mechanical properties. White cast iron, once considered too brittle for many applications, now shows promise as a material that can be shaped and strengthened for demanding roles. Future work could explore other alloying elements or advanced heat treatment techniques to further enhance white cast iron properties. Overall, this study contributes to a broader understanding of white cast iron and its potential in modern engineering.