The pursuit of enhanced driving comfort and fuel efficiency remains a paramount objective within the automotive industry. The transmission, as one of the three core powertrain components, plays a critical role in this endeavor. Advanced multi-speed automatic transmissions, such as 9-speed units, utilize complex nested planetary gear sets to provide closer gear ratios and more efficient engine operation compared to their predecessors. The production of the structural housing for such sophisticated systems via high-pressure die casting (HPDC) presents significant challenges, primarily concerning internal quality and the minimization of defects like gas porosity. This study focuses on the optimization of a key HPDC process parameter—the injection phase switching position—for a 9-speed automatic transmission main housing. Utilizing numerical simulation to analyze melt flow behavior and subsequent experimental validation, the research aims to establish a robust process window for producing high-integrity shell castings.

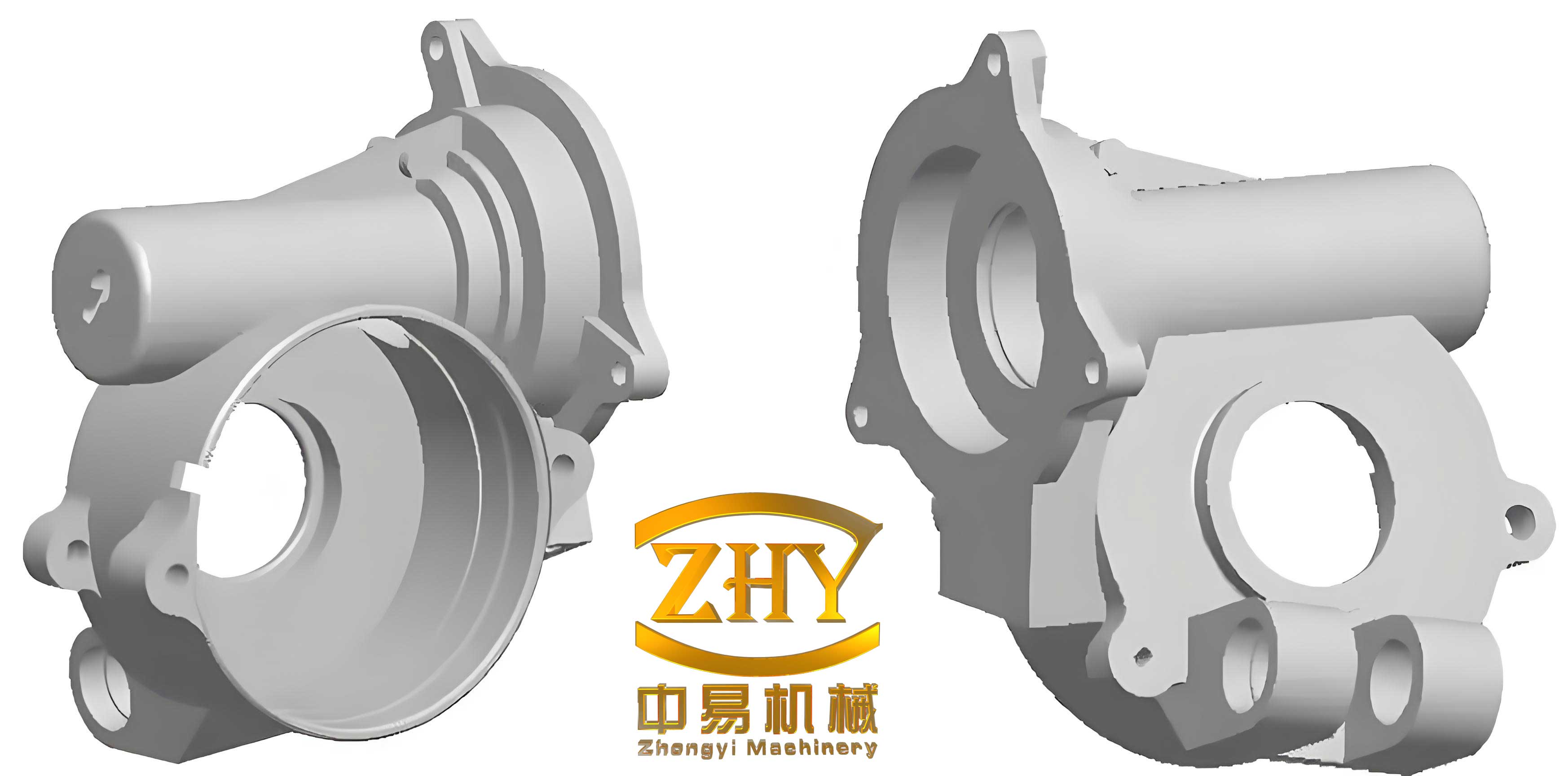

The main housing for a 9AT transmission is a large, structurally complex shell casting. Its geometry is characterized by an irregular shape with varying wall thicknesses and numerous internal ribs, bosses, and channels necessary for mounting bearings, shafts, and valve bodies. The average wall thickness is approximately 6 mm, with sections ranging from thin walls of about 4 mm to thick masses up to 30 mm. This disparity, combined with the intricate internal features, creates inherent difficulties during die casting, including turbulent filling, air entrapment, and localized shrinkage. The successful production of this component demands precise control over the molten metal flow to ensure complete cavity filling while minimizing turbulence that leads to defects. The exterior envelope dimensions are roughly 470 mm x 400 mm x 400 mm, with a final part weight of about 12.6 kg. The mechanical demands are high, requiring sufficient strength and rigidity to maintain accurate alignment of internal components under dynamic loads.

The alloy selected for this shell casting is ADC12 (A383), a common die-casting aluminum-silicon alloy. Its excellent castability, good corrosion resistance, and reasonable mechanical properties make it suitable for large, thin-walled components like transmission housings. The chemical composition is detailed in Table 1.

| Element | Composition (wt.%) |

|---|---|

| Si | 9.6 – 12.0 |

| Cu | 1.5 – 3.5 |

| Fe | ≤ 1.3 |

| Mn | ≤ 0.5 |

| Mg | ≤ 0.3 |

| Zn | ≤ 1.0 |

| Ni | ≤ 0.55 |

| Al | Balance |

The gating system design is fundamental for directing molten metal into the cavity. For this asymmetrical shell casting with deep and shallow sections, the ingate was positioned to favor filling the deeper cavity regions. A multi-gate or fan-type runner system was employed to distribute flow, with a dedicated branch feeding the complex valve body mounting face on one side. Effective gating helps promote laminar flow and reduces jetting. The total projected area of the casting and overflow system was calculated to be approximately 265,327 mm².

Based on standard HPDC practice and machine capabilities, initial process parameters were established. A Buhler 3050t die casting machine was selected. Key parameters include:

– Melt Pouring Temperature: 680 °C

– Die Initial Temperature: 200 °C

– Slow Shot Phase Velocity: 0.2 m/s

– Fast Shot Phase Velocity: 3.5 m/s

– Intensification Pressure: 80 MPa

– Shot Sleeve Diameter: 150 mm

– Total Shot Sleeve Length: 800 mm

The core variable under investigation is the position within the shot sleeve where the plunger velocity switches from the slow phase to the fast phase. This switching position critically influences how the sleeve is pre-filled and the initial condition of the molten metal as it enters the die cavity. Premature switching can cause severe turbulence and air entrapment, while excessively delayed switching might lead to premature solidification or insufficient energy for complete filling. Three distinct switching positions were defined for simulation, corresponding to different states of metal advancement at the moment of switching:

– Scheme 1 (480 mm): Switching occurs as the melt front just reaches the ingates.

– Scheme 2 (520 mm): Switching occurs after the melt has partially filled the main runner branches and begun merging within the cavity.

– Scheme 3 (560 mm): Switching is delayed until the melt from the main gate and the side branch have substantially filled their respective cavity regions and are poised to merge smoothly.

The filling process was simulated using a commercial computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software capable of modeling free-surface flows. The analysis focused on flow patterns, velocity fields, and the probability of air entrapment. The governing equations for fluid flow and heat transfer were solved. The momentum conservation is described by the Navier-Stokes equations for an incompressible fluid with a free surface:

$$ \rho \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{u} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{u} \right) = -\nabla p + \mu \nabla^2 \mathbf{u} + \rho \mathbf{g} $$

where $ \rho $ is the fluid density, $ \mathbf{u} $ is the velocity vector, $ t $ is time, $ p $ is pressure, $ \mu $ is the dynamic viscosity, and $ \mathbf{g} $ is gravitational acceleration. The Volume of Fluid (VOF) method was used to track the melt-air interface. The energy equation, including latent heat release during solidification, was also solved:

$$ \rho C_p \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} + \mathbf{u} \cdot \nabla T \right) = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + S $$

where $ C_p $ is specific heat, $ T $ is temperature, $ k $ is thermal conductivity, and $ S $ is a source term for latent heat.

The simulation results for Scheme 1 revealed significant issues. As the fast shot was initiated precisely at the ingates, the molten metal jetted into the cavity at high speed. This caused severe splashing and overturning of the flow front, particularly in the shallow section of the shell casting. The resulting turbulent flow led to the encapsulation of large air pockets. The simulated air entrapment probability exceeded 30% in large areas, with some localized zones reaching 50%.

Scheme 2 showed marked improvement. By allowing the slow shot phase to continue until the melt fronts from multiple gates began to merge, the initial high-speed impact was mitigated. The flow was more stable upon fast shot initiation. However, a minor jetting phenomenon was still observed in the shallow cavity area as it filled slightly faster than the deeper sections, leading to localized air entrapment with probabilities up to 50% in the last-to-fill regions.

Scheme 3 demonstrated the most favorable filling pattern. Delaying the switch until the cavity was significantly pre-filled (at 560 mm) resulted in a near-laminar flow advance during the fast shot phase. The melt front progressed uniformly, minimizing turbulence and wave formation. The air entrapment probability was substantially reduced across the entire shell casting. The shallow section showed probabilities below 13%, and the final filling zones had probabilities under 30%. A comparative summary of the maximum air entrapment probability in critical zones is presented in Table 2.

| Switching Scheme | Switching Position (mm) | Max Air Entrapment Probability (Shallow Zone) | Max Air Entrapment Probability (Final Fill Zone) | Flow Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | 480 | > 30% | ~50% | Severe Jetting, Highly Turbulent |

| Scheme 2 | 520 | ~20% | ~50% | Moderate Jetting, Improved Stability |

| Scheme 3 | 560 | < 13% | < 30% | Near-Laminar, Uniform Fill |

The underlying physics can be explained by analyzing the kinetic energy of the melt stream. The kinetic energy ($E_k$) entering the cavity at the start of the fast shot is proportional to the square of the velocity and the mass of the moving melt column:

$$ E_k \propto \frac{1}{2} m v^2 $$

where $m$ is the effective mass of the molten metal set into motion at the switch point, and $v$ is the fast shot velocity. In Scheme 1, $m$ is relatively small (mainly the metal in the runners), but it is subjected to the full fast shot velocity $v$ immediately upon entering the empty cavity, resulting in high $E_k$ and destructive impact. In Scheme 3, a larger mass $m$ (metal already in the cavity) is accelerated. While the velocity $v$ is the same, the pre-existing metal in the cavity acts as a buffer, dampening the impact force and distributing the kinetic energy more uniformly. This promotes a displacement-style filling rather than a jetting-style filling, drastically reducing air entrainment. The optimal switch point thus represents a balance where the sleeve is sufficiently pre-filled to avoid jetting, but not so full that excessive pressure is needed to accelerate the metal or that the metal begins to solidify prematurely.

Based on the simulation results, Scheme 3 parameters (slow shot: 0.2 m/s, fast shot: 3.5 m/s, switch point: 560 mm) were selected for physical trial production. The produced shell castings exhibited excellent visual quality with complete fill, sharp features, and no surface defects like cold shuts or misruns. Metallographic samples were extracted from locations near the ingate and from a distant, thick-sectioned area (simulating the last-to-fill zone).

The microstructure of the ADC12 alloy in the housing consisted primarily of α-Al dendrites/grains and the Al-Si eutectic phase. The near-ingate region showed a slightly coarser structure with α-Al phases exhibiting both dendritic and rosette morphologies, and the eutectic silicon appearing as fine needles or plates. The area corresponding to the final fill zone displayed a finer microstructure due to higher effective cooling rates, with more globular α-Al grains and finer eutectic silicon particles. This microstructural refinement in different sections is consistent with expected thermal history during solidification. The microstructure was generally dense with no large, visible porosity, corroborating the low air entrapment probability predicted by the simulation for the optimized switch point.

Tensile test specimens were machined from the same sampled locations. The results, presented in Table 3, confirm that the mechanical properties meet and exceed the specified requirements for the transmission housing (typically a minimum tensile strength of 190 MPa and elongation over 1%). The properties are superior near the ingate due to more favorable solidification conditions, but even the properties from the final fill zone are satisfactory. The achieved elongation values indicate a reasonable level of ductility for a die-cast component, often limited by porosity.

| Sample Location | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Near Ingate | 272.0 | 3.4 |

| Final Fill Zone | 230.6 | 2.7 |

| Specification Requirement | > 190 | > 1.0 |

In conclusion, this investigation systematically optimized the injection phase switching position for the high-pressure die casting of a complex aluminum transmission main housing. Numerical simulation proved to be an effective tool for visualizing and quantifying the impact of this critical parameter on melt flow and defect formation. The results demonstrated that an early switch point (480 mm) leads to turbulent jetting and high air entrapment. A moderately delayed switch (520 mm) improves flow but may not fully stabilize the fill in complex geometries. An optimally delayed switch point (560 mm for this specific shell casting), where the cavity is significantly pre-filled before high-speed injection, promotes uniform, laminar-like filling and minimizes the probability of gas porosity. Experimental trials using the optimized parameter set yielded shell castings with sound surface quality, dense microstructure, and mechanical properties that conformed to all specifications. This methodology underscores the importance of precise control over the injection profile in HPDC, particularly for large and structurally critical shell castings, to achieve high internal quality and performance reliability.