In my extensive experience with investment casting, particularly for complex shell castings, I have encountered numerous challenges related to dimensional accuracy, defect prevention, and process efficiency. Shell castings, characterized by their hollow or enclosure structures, often feature varying wall thicknesses and intricate geometries that demand meticulous工艺设计. This article delves into a specific case involving a thin-walled shell casting, where I aimed to address shrinkage porosity through comprehensive process optimization. The focus is on applying first-principles analysis, mathematical modeling, and empirical validations to enhance the quality and yield of such shell castings. Throughout this discussion, the term “shell castings” will be emphasized to underscore its relevance in precision casting applications.

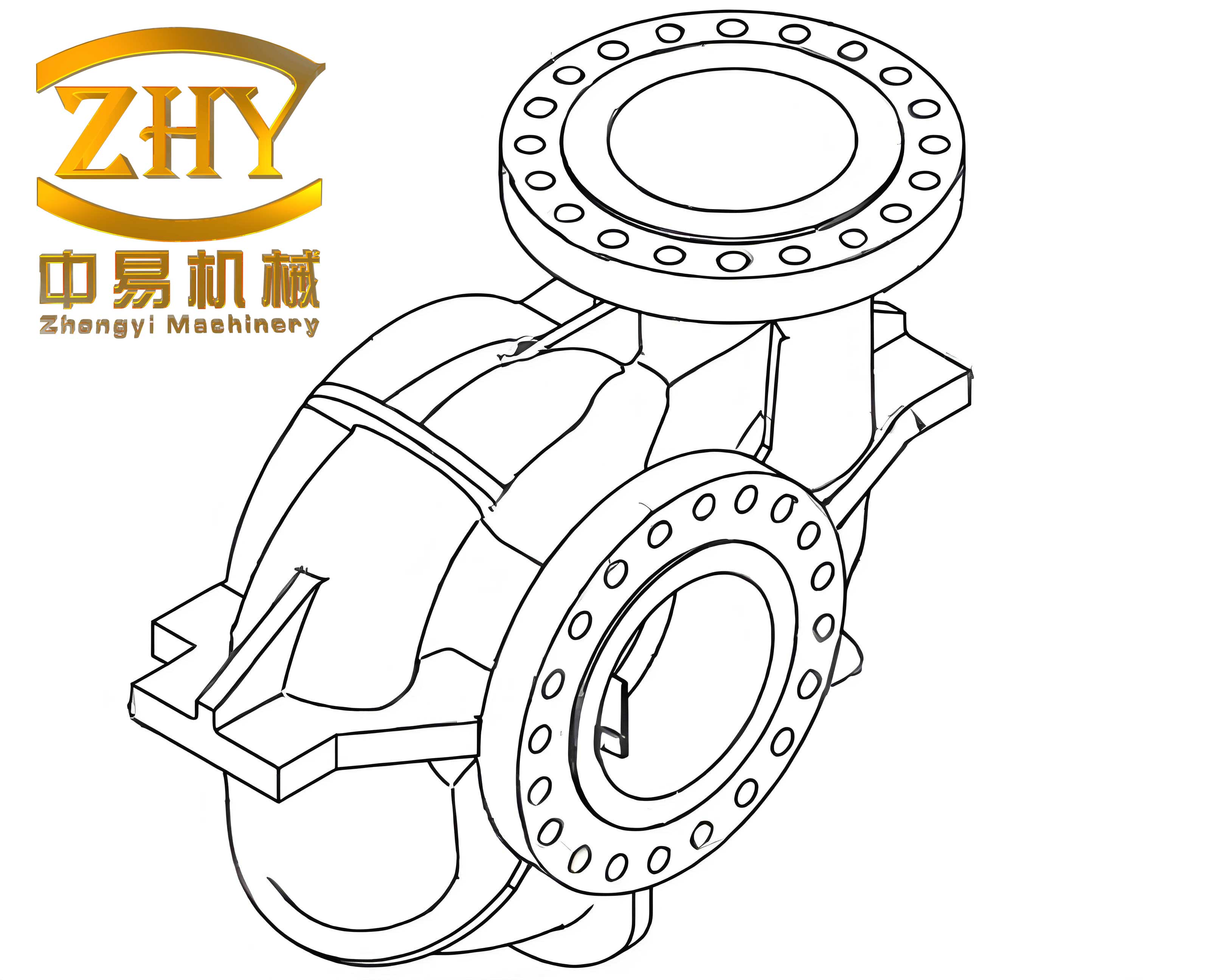

The shell casting in question had an external轮廓尺寸 of 28 mm × 38 mm × 14 mm, with a mass of approximately 6 grams. Its wall thickness varied significantly, ranging from 2 mm at the thinnest sections to 12 mm at the thickest, creating a substantial disparity that complicates solidification dynamics. The material was ZG35CrMnSi, a low-alloy steel requiring stringent nondestructive testing per technical协议, including magnetic particle and X-ray inspections. Initial production runs revealed persistent shrinkage porosity at the thin-walled regions, specifically in areas with recessed grooves, which jeopardized the structural integrity of these shell castings. This defect not only compromised performance but also led to high rejection rates, necessitating an in-depth investigation and redesign.

To systematically tackle this issue, I first analyzed the defect location using solidification simulation principles. Shrinkage in shell castings typically arises from inadequate feeding during the liquid-to-solid transition, especially where thermal gradients are steep. For a thin wall adjacent to a thicker section, the solidification front progresses rapidly, isolating liquid pools that cannot be replenished. The presence of a groove exacerbated this by acting as a heat sink due to ceramic shell material accumulation, further delaying local cooling. I derived a simplified model based on Chvorinov’s rule to estimate the solidification time differential:

$$ t = C \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^2 $$

where \( t \) is the solidification time, \( V \) is the volume of the casting section, \( A \) is its surface area, and \( C \) is a mold constant dependent on material properties and process conditions. For the thin-walled region (2 mm thickness) versus the thick section (12 mm), the modulus \( \frac{V}{A} \) differs markedly, leading to disparate solidification rates. Assuming a planar geometry approximation, the modulus for a thin plate can be expressed as:

$$ M_{\text{thin}} = \frac{t_{\text{wall}}}{2} $$

where \( t_{\text{wall}} \) is the wall thickness. Thus, for the 2 mm section, \( M_{\text{thin}} = 1 \, \text{mm} \), while for the 12 mm section, \( M_{\text{thick}} = 6 \, \text{mm} \). Plugging into Chvorinov’s rule, the solidification time ratio becomes:

$$ \frac{t_{\text{thick}}}{t_{\text{thin}}} = \left( \frac{M_{\text{thick}}}{M_{\text{thin}}} \right)^2 = \left( \frac{6}{1} \right)^2 = 36 $$

This indicates that the thick section solidifies approximately 36 times slower than the thin wall, creating a significant risk of shrinkage in the thin area if feeding paths are obstructed. For shell castings with such variations, ensuring continuous liquid metal supply through strategic gating is paramount.

My initial浇注系统设计 placed inner gates at the thick热节 locations, as shown in earlier schematics. However, this approach failed to address the groove area, where shell material buildup during investment formed an insulating barrier. The effective modulus in the groove zone increased due to the added ceramic thickness, which I modeled as an equivalent thermal resistance. The heat transfer rate \( Q \) through the shell can be described by Fourier’s law:

$$ Q = -k A \frac{\Delta T}{\Delta x} $$

where \( k \) is the thermal conductivity of the shell material, \( A \) is the area, \( \Delta T \) is the temperature difference, and \( \Delta x \) is the shell thickness. Accumulation in the groove raised \( \Delta x \), reducing \( Q \) and prolonging local solidification. This created a pseudo-hot spot, necessitating a direct feeding source. Hence, I redesigned the gating system to include an additional inner gate at the groove, with a cross-section of 4 mm × 12 mm, positioned on a flat surface to facilitate post-casting removal. The feeding distance \( L_f \) for effective补缩 can be estimated using:

$$ L_f = \sqrt{\frac{2 \sigma \cos \theta}{\rho g}} $$

where \( \sigma \) is the surface tension, \( \theta \) is the contact angle, \( \rho \) is the density, and \( g \) is gravity. For steel alloys, this typically ranges from 50 to 100 mm, but for thin-walled shell castings, I保守地 set it at 25 mm to ensure robustness. The cluster arrangement, comprising 12 shell castings per tree, maintained a minimum distance of 25 mm from the central sprue to minimize radiative heat effects.

The cluster configuration was pivotal. I oriented the groove structures outward, which offered several advantages for shell castings: improved slurry drainage during coating, better sand distribution观察, and enhanced drying uniformity. This alignment prevented local shell thickening and reduced cracking risks from moisture entrapment. To quantify the drying process, I considered the diffusion equation for moisture removal:

$$ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D \nabla^2 C $$

where \( C \) is the moisture concentration, \( t \) is time, and \( D \) is the diffusivity. An outward-facing groove allows for symmetric boundary conditions, accelerating drying. In contrast, inward-facing grooves create stagnant air pockets, prolonging drying and inducing stresses. The table below summarizes the cluster design parameters for these shell castings:

| Parameter | Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Shell Castings per Tree | 12 | Balances productivity and thermal mass |

| Distance from Sprue | ≥25 mm | Reduces heat辐射影响 |

| Groove Orientation | Outward | Facilitates coating and drying |

| Sprue Diameter | 30 mm | Provides adequate metal flow |

Moving to the shell-building process, I employed a 5-layer system followed by a seal coat, tailored for small shell castings. The layers were designed to balance strength, permeability, and thermal stability. The slurry viscosity and sand grit selections were optimized based on empirical data from similar shell castings. A key aspect was ensuring uniform coating in the groove areas to avoid bridging or excessive buildup. I used a dipping and stuccoing sequence, with careful air-blowing between layers to dislodge loose grains. The shell thickness \( \delta \) as a function of layer number \( n \) can be approximated by:

$$ \delta(n) = \delta_0 + \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \alpha_i \cdot \eta_i \right) $$

where \( \delta_0 \) is the initial wax pattern thickness, \( \alpha_i \) is the coating thickness per layer, and \( \eta_i \) is a uniformity factor (ideally close to 1). For the groove, I aimed for \( \eta_i \geq 0.8 \) to prevent local thickening. The detailed shell-making schedule is presented in the table below, which has been validated for numerous shell castings:

| Layer Number | Slurry Material (Mesh) | Viscosity (s) | Stucco Material (Mesh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zircon Flour (320) | 36 | Zircon Sand (120) |

| 2 | Mullite Flour (200) | 15 | Mullite Sand (30-60) |

| 3 | Mullite Flour (200) | 12 | Mullite Sand (16-30) |

| 4 | Mullite Flour (200) | 12 | Mullite Sand (16-30) |

| 5 | Mullite Flour (200) | 12 | Mullite Sand (16-30) |

| 6 (Seal Coat) | Mullite Flour (200) | 10 | None |

Drying conditions were strictly controlled, with air velocity in the drying chamber maintained at 3–5 m/s to promote even moisture evaporation. For shell castings with recessed features, this is critical to avoid differential shrinkage in the ceramic mold. The drying time \( t_d \) for each layer can be estimated using a simplified model:

$$ t_d = \frac{\rho_w L^2}{2D \Delta C} $$

where \( \rho_w \) is the water density, \( L \) is the characteristic length (e.g., shell thickness), \( D \) is the diffusion coefficient, and \( \Delta C \) is the concentration gradient. In practice, I set layer drying times based on ambient humidity and temperature monitoring, typically 4–6 hours per layer for these shell castings.

Dewaxing was executed using a high-pressure steam autoclave, with parameters calibrated to prevent shell cracking or wax残留. Rapid transfer (within 60 seconds) from the shell-making area to the autoclave minimized thermal shocks. The dewaxing kinetics can be described by the heat transfer equation for wax melting:

$$ \frac{dm}{dt} = \frac{k A (T_s – T_m)}{\lambda L} $$

where \( dm/dt \) is the wax removal rate, \( k \) is the thermal conductivity of the shell, \( A \) is the surface area, \( T_s \) is the steam temperature, \( T_m \) is the wax melting point, \( \lambda \) is the latent heat, and \( L \) is the shell thickness. The optimized parameters for these shell castings are tabulated below:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Inner Pot Temperature | 175–185°C |

| Steam Boiler Pressure Upper Limit | 0.8 ± 0.1 MPa |

| Steam Boiler Pressure Lower Limit | 0.76 ± 0.1 MPa |

| Autoclave Pressurization Time | 1000 ± 20 s |

| Dewaxing Time | 20 ± 5 s |

| Pre-drain Pressure | 0.05–0.06 MPa |

| Wax Drain Time | 100–500 s |

| Water Drain Time | 50 ± 2 s |

Following dewaxing, the shells were fired at 1050°C for 50 minutes to develop mechanical strength and remove residual volatiles. The firing process also affects the thermal conductivity of the shell, which influences solidification. I measured the effective conductivity \( k_{\text{eff}} \) using a transient plane source method, yielding values around 0.5–0.7 W/m·K for the multilayer shell, suitable for steel shell castings.

Melting and pouring were conducted in a medium-frequency induction furnace using母合金钢棒. The pouring temperature was set at 1630°C ± 10°C, based on the superheat required for fluidity without excessive gas absorption. The theoretical pouring time \( t_p \) for thin-walled shell castings can be derived from Bernoulli’s equation:

$$ t_p = \frac{V}{\mu A \sqrt{2gh}} $$

where \( V \) is the casting volume, \( \mu \) is the discharge coefficient (typically 0.6–0.8 for investment casting), \( A \) is the sprue cross-sectional area, \( g \) is gravity, and \( h \) is the metallostatic head. For our cluster, \( t_p \) was approximately 2–3 seconds. After pouring, the molds were placed on sand beds and covered with exothermic insulating powder to enhance feeding from the gating system. The补缩 efficacy \( E_f \) can be expressed as:

$$ E_f = \frac{\Delta H_f \cdot V_f}{Q_{\text{loss}}} $$

where \( \Delta H_f \) is the latent heat of fusion, \( V_f \) is the volume of feeder metal, and \( Q_{\text{loss}} \) is the heat loss from the casting. By optimizing the gating design, I aimed for \( E_f > 1 \) for the critical sections.

To validate the improvements, I conducted comparative trials with 60 shell castings per gating design. The results starkly highlighted the impact of the optimized system. Initially, with gates only at thick sections, the合格率 was a mere 10%, with shrinkage defects concentrated in the thin-walled grooves. After introducing the additional gate at the groove, the合格率 soared to 86.7%. This was corroborated by X-ray imaging, which showed no porosity in the previously problematic areas. The table below summarizes the trial outcomes for these shell castings:

| Gating Design | Number of Shell Castings Produced | Number of Acceptable Shell Castings | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original (Gates at Thick Sections Only) | 60 | 6 | 10.0 |

| Optimized (Additional Gate at Groove) | 60 | 52 | 86.7 |

The dramatic improvement underscores the importance of direct feeding for thin-walled features in shell castings. Further analysis using thermal modeling software confirmed that the added gate provided a continuous liquid path, reducing the temperature gradient \( \nabla T \) across the thin wall. The solidification front velocity \( v \) can be related to the gradient by:

$$ v = \frac{k_s \nabla T}{\rho L_f} $$

where \( k_s \) is the solid thermal conductivity, \( \rho \) is density, and \( L_f \) is latent heat. A lower \( \nabla T \) achieved through better feeding slows \( v \), allowing for more orderly solidification and fewer defects.

In批量 production with the optimized process, the yield for these shell castings consistently exceeded 95%, demonstrating the robustness of the approach. Key factors included meticulous control of shell-building parameters, precise gating geometry, and strict adherence to thermal cycles. For similar shell castings, I recommend conducting pre-production simulations using finite element analysis to predict hot spots and optimize gating layouts. The general principle can be encapsulated in a design rule for shell castings: for any thin section adjacent to a thicker mass or recess, ensure a dedicated feeding channel with a modulus ratio \( M_{\text{gate}} / M_{\text{casting}} \geq 1.2 \) to guarantee adequate metal supply.

Moreover, the orientation of complex features like grooves outward during clustering is a best practice for shell castings, as it simplifies manual operations and improves process consistency. This aligns with broader trends in investment casting toward digitalization and data-driven optimization, where real-time monitoring of slurry viscosity and drying conditions can further enhance quality for shell castings.

In conclusion, the successful resolution of shrinkage porosity in this thin-walled shell casting hinged on a holistic process redesign. By integrating浇注系统 modifications with careful cluster planning and shell-building controls, I achieved significant quality improvements. The mathematical models and empirical data presented here provide a framework for addressing similar challenges in shell castings across various industries. Future work could explore advanced materials for shells to further reduce thermal resistance or machine learning algorithms to predict defect probabilities. Ultimately, the continuous refinement of investment casting techniques remains essential for producing high-integrity shell castings that meet evolving engineering demands.