In my extensive experience within investment casting production, addressing shrinkage in casting remains one of the most persistent and costly challenges. Shrinkage porosity, a defect characterized by dispersed micro-porosity or localized cavities, severely compromises the mechanical integrity and pressure tightness of components. A significant root cause, often underestimated during product design, is non-optimal casting geometry. Structural features like abrupt wall thickness variations, isolated heavy sections, and restricted feeding paths create thermal hotspots that hinder directional solidification and effective liquid metal feeding. For processes like silica sol investment casting, where process design flexibility is inherently limited, an ill-conceived part geometry can render even the most sophisticated gating and risering systems ineffective. I have witnessed scrap rates between 10% to 30% directly attributable to such design-induced shrinkage in casting, defects that only reveal themselves during machining, leading to substantial material and labor losses. This article, drawn from firsthand problem-solving, details common structural pitfalls and presents geometric optimization strategies validated through batch production to mitigate shrinkage in casting.

The fundamental principle behind preventing shrinkage in casting is ensuring a continuous gradient of solidification from the farthest point of the casting toward the feeder (riser). This directional solidification allows the feeder to supply liquid metal to compensate for the volumetric contraction of the solidifying alloy. When the casting structure disrupts this thermal gradient, shrinkage defects form. The key parameters influencing this are the modulus (volume-to-surface area ratio) of sections and the connectivity between sections. The thermal modulus, M, is often approximated for simple shapes as:

$$ M = \frac{V}{A} $$

where V is the volume and A is the cooling surface area. A higher modulus indicates a slower cooling rate. Shrinkage in casting occurs at locations with a locally high modulus relative to the feeding path, creating a “hot spot” that solidifies last without access to liquid feed metal.

One prevalent category of problems stems from inadequate feeding due to poor thermal sequencing. I recall a pump body casting where shrinkage in casting appeared at the roots of side flanges and an internal bore. The original design featured a thin internal bore with poor heat dissipation, adjacent to thicker flange sections. The gating was attached to the flanges, causing them to cool rapidly. Consequently, the hotter internal section solidified later but was isolated from the now-solidified feeders. The solution was not to enlarge the risers but to reorganize the thermal field by reversing the metal flow direction during pouring. This kept the feeder at the flange hotter for longer, establishing a proper thermal gradient and enabling effective feeding, thereby eliminating the shrinkage in casting completely. This case underscores that feeder placement must be relative to the thermal mass, not just the geometric mass.

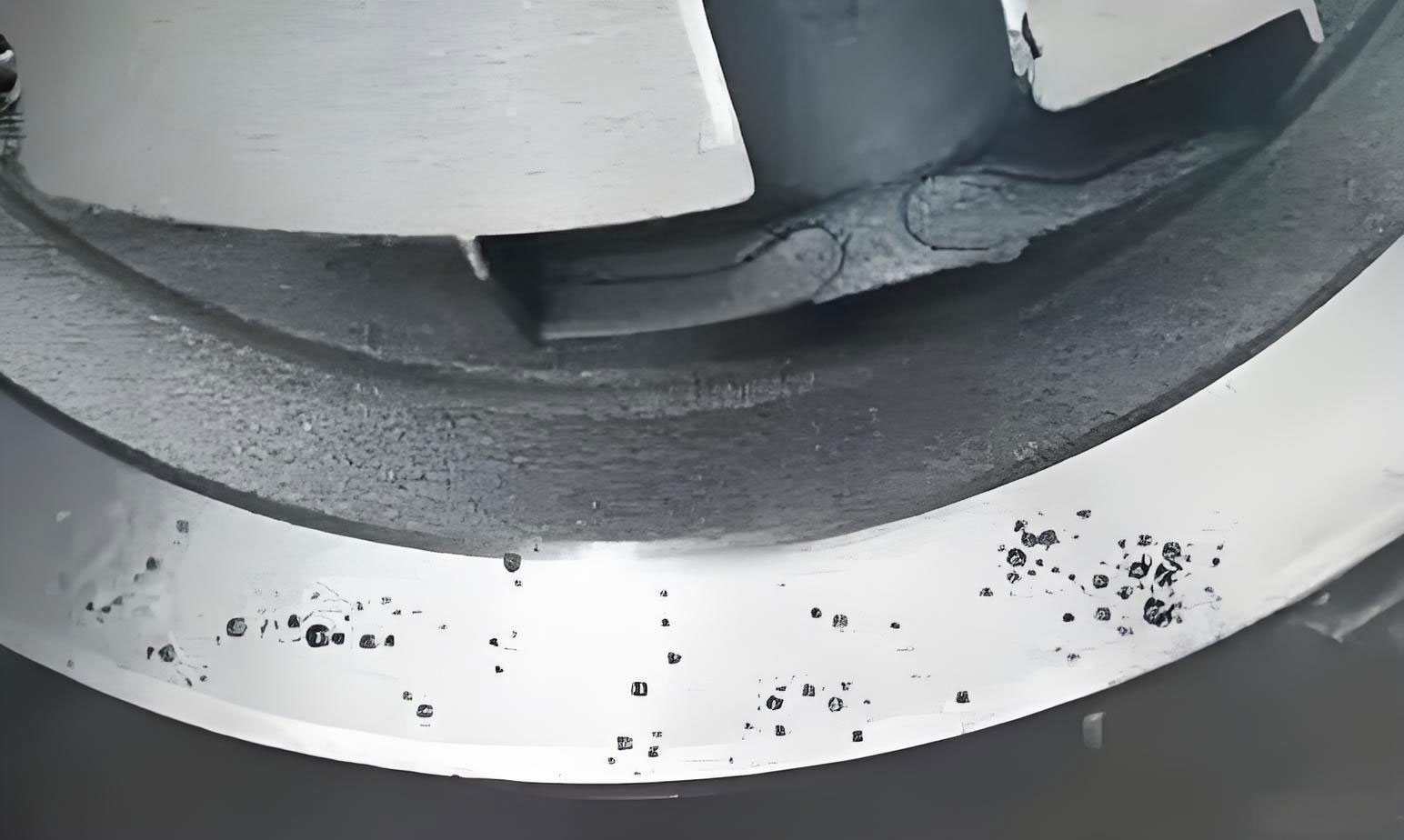

A more subtle cause of shrinkage in casting is localized overheating from minimal inter-geometry spacing. In another pump body, a 6mm wall had a 30mm diameter boss whose outer arc was merely 3mm away from the main casting wall. Despite simulation suggesting sufficiency, a 40% defect rate occurred at this boss. Increasing the feeder size provided only marginal improvement. Analysis revealed that the narrow 3mm gap acted as an insulating air pocket, causing the entire region—boss and adjacent wall—to behave as a single, massive thermal node with a modulus higher than the intended feeder. The boss, though seemingly small, became the hottest spot. The definitive fix was a structural change: elongating the flange and boss outward by 10mm. This increased the spacing, improved heat extraction into the mold, reduced the effective thermal modulus of the area, and resolved the shrinkage in casting. The relationship for heat extraction through a narrow gap can be complex, but simplifying, the thermal resistance of an air gap is inversely proportional to its width. A smaller gap dramatically increases local superheat, promoting shrinkage in casting.

Restricted feeding channels are a classic designer oversight leading to shrinkage in casting. Even if a hot spot is identified and a feeder is placed, if the connecting “neck” between them freezes too early, feeding ceases. I encountered this in a valve body where a hot section was connected to the feeder via a 3mm thick channel. The internal section, having a high modulus, required prolonged feeding, but the thin channel solidified rapidly, blocking the path. The result was subsurface shrinkage in casting. The necessary design change was to thicken the feeding channel from 3mm to 6mm, increasing its solidification time and ensuring it remained open to transmit liquid metal. This principle can be quantified using Chvorinov’s rule for solidification time, t:

$$ t = C \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n = C M^n $$

where C is a mold constant and n is an exponent (often ~2). For a feeding channel to function, its solidification time (t_channel) must be greater than that of the hot spot it feeds (t_hotspot). Therefore, we require:

$$ M_{channel} > M_{hotspot} $$

Optimizing the geometry to meet this condition is crucial to prevent shrinkage in casting.

| Structural Cause Category | Typical Geometric Feature | Consequence | Proposed Geometric Optimization | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Feeding Sequence | Internal thin sections gated from thick sections. | Early freezing of feeders isolates hot sections. | Re-orient gating to place feeder on thickest/heaviest section; redesign for progressive thickness increase toward feeder. | Establish directional solidification toward the feeder. |

| Localized Overheating | Small bosses, ribs, or protrusions very close to main walls. | Creates an insulated macro-hotspot with high thermal modulus. | Increase local spacing to improve heat dissipation; blend radii to reduce modulus concentration. | Reduce thermal modulus of isolated features; improve heat extraction. |

| Restricted Feeding Channel | Thin section connecting a hot spot to a feeder. | Channel freezes prematurely, blocking feeding path. | Increase channel thickness or width (increase its modulus). | Ensure feeding channel modulus > fed section modulus. |

| Heavy Internal Sections | Thick internal walls or cores surrounded by thinner external walls. | Poor heat dissipation creates severe hot spots with no accessible feeder. | Core out the heavy section if possible; if not, design as a solid block fed directly by a major feeder. | Provide direct and ample feeding to high-modulus internal volumes. |

| Isolated Hot Spots | Intersections of walls, sharp corners, or small, heavy masses. | Localized shrinkage porosity due to lack of feeding direction. | Add “cooling fins” or chills externally; modify intersection geometry to promote simultaneous solidification. | Promote simultaneous solidification by enhancing local cooling. |

The challenge of heavy internal sections presents a severe case of shrinkage in casting. A large pump body with an internal wall thickness exceeding 30mm more than the external walls exhibited massive shrinkage. External feeders were useless because the feeding path through the thin outer wall was blocked long before the internal heavy section solidified. The solution was a radical structural change: filling the central bore to make it solid, thereby transforming the internal heavy section into a continuous, feedable volume from the top feeder. This highlights that sometimes the most effective way to eliminate shrinkage in casting is to simplify the internal geometry to allow for straightforward feeding, with excess material removed later by machining. The modulus of such a section, if hollow, is difficult to feed; if solid, it can be integrated into the feeding system.

Isolated hot spots, such as those at wall junctions or small bosses, are ubiquitous sources of shrinkage in casting. A bracket casting with a T-junction consistently showed porosity. Standard feeding solutions failed due to space constraints. The successful approach was to promote simultaneous solidification across the hot spot by enhancing localized cooling. We achieved this by applying mold chills (zircon sand inserts with high thermal conductivity) directly onto the shell opposite the hot spot. This increased the local cooling rate, reducing the thermal modulus differential and minimizing the liquid volume needing interdendritic feeding. The effectiveness of a chill can be estimated by considering the increased heat flux. The heat extraction rate Q can be modeled as:

$$ Q = h A (T_{cast} – T_{mold}) $$

where h is the heat transfer coefficient, significantly higher for a chill than for the standard ceramic shell. By increasing h geometrically at the hot spot, we drastically reduce its effective solidification time, aligning it with surrounding sections and preventing shrinkage in casting.

To systematically address shrinkage in casting, I employ a structured design review protocol. The following table summarizes quantitative guidelines we’ve developed to assess geometric suitability and prevent shrinkage in casting.

| Parameter | Rule of Thumb | Rationale & Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Wall Thickness Ratio (Adjacent Sections) | Not to exceed 2:1 | Prevents excessive thermal gradient that can isolate sections. Aim for $$ \frac{t_{thick}}{t_{thin}} \leq 2 $$ |

| Minimum Feeding Channel Modulus | >= 1.1 * Modulus of Fed Section | Ensures channel stays open. $$ M_{channel} \geq 1.1 \times M_{hotspot} $$ |

| Isolated Feature Spacing | Distance to adjacent wall >= feature height/3 | Prevents formation of combined thermal mass. $$ d \geq \frac{h}{3} $$ |

| Internal Corner Radii | R >= 0.3 * Wall Thickness | Reduces modulus concentration at junctions. $$ R_{internal} \geq 0.3t $$ |

| Feeder Accessibility Criterion | Every heavy section (M > M_avg) must have a direct, modulous-compliant path to a feeder. | Ensures feed metal can reach all potential shrinkage sites. |

Beyond these rules, advanced simulation plays a pivotal role. Modern solidification modeling software allows us to calculate the Niyama criterion, a reliable predictor for shrinkage in casting. The Niyama criterion, Ny, is derived from local thermal parameters:

$$ Ny = \frac{G}{\sqrt{\dot{T}}} $$

where G is the temperature gradient (°C/cm) and Ṫ is the cooling rate (°C/s). Locations where Ny falls below a critical threshold (material-dependent) are highly prone to shrinkage porosity. By iterating geometric changes in the simulation environment—such as adding fillets, adjusting wall thicknesses, or repositioning features—we can visually and quantitatively see the reduction in low-Niyama regions, correlating directly with reduced risk of shrinkage in casting. This iterative simulation-driven design process is now indispensable for complex components.

Another critical aspect is the interaction between alloy characteristics and geometry. The susceptibility to shrinkage in casting varies with the alloy’s freezing range. For a long-freezing-range alloy, even minor thermal hotspots can lead to extensive microporosity. The critical modulus for feeding, M_c, can be approximated as:

$$ M_c = k \cdot \Delta T_f^{1/2} $$

where k is a constant and ΔT_f is the freezing range. For such alloys, geometric uniformity is even more paramount. Therefore, when advising on design, we must consider the alloy-specific “shrinkage in casting” propensity and tailor geometric recommendations accordingly.

In practice, convincing product designers to modify geometry requires clear communication of cost implications. We demonstrate that a slight increase in material usage or a minor design change can reduce total cost by slashing scrap rates and machining rejects related to shrinkage in casting. For instance, adding a small rib or gusset to improve feeding can be far cheaper than 100% X-ray inspection or post-casting impregnation processes. The economic model is straightforward: the cost of prevention (design change) is often an order of magnitude lower than the cost of failure (scrap, rework, delayed delivery).

To consolidate the learning, let’s derive a generalized approach for designers. When drafting a component for investment casting, ask these sequence questions to avoid shrinkage in casting:

- Are wall thickness transitions gradual (tapered) rather than abrupt?

- For any local increase in thickness (boss, pad, intersection), is there a direct and adequately sized path for liquid metal to feed it from a riser?

- Are internal cavities and cores truly necessary, or could they be made solid and machined later to improve castability?

- Can sharp internal corners be replaced with generous radii to reduce stress concentration and thermal modulus?

- Is the overall shape conducive to establishing a clear solidification direction from the farthest point to the feeder?

Answering “no” to any of these flags a potential for shrinkage in casting and warrants a design review.

In conclusion, the battle against shrinkage in casting is fundamentally won on the drawing board. Through countless production trials and analyses, I have found that geometric optimization is the most robust and sustainable solution. While foundry engineers can sometimes circumvent poor design with elaborate and costly process innovations, this is not reliable for volume production. Proactive collaboration between product designers and foundry engineers, guided by principles of thermal modulus management and directional solidification, is essential. By embedding castability considerations—such as uniform wall thickness, accessible feeding paths, and minimized isolated thermal masses—into the initial design phase, we can dramatically reduce the incidence of shrinkage in casting. This not only boosts quality and yield but also shortens lead times and reduces total cost. The examples and guidelines shared here, grounded in firsthand experience, underscore that preventing shrinkage in casting through intelligent geometric design is not merely an option but a critical imperative for competitive and reliable casting production.