In my experience as a casting engineer, the production of complex aluminum alloy shell castings presents significant challenges due to their intricate geometries, varying wall thicknesses, and high-quality requirements. These shell castings are critical components in aerospace, automotive, and industrial applications, where structural integrity and surface finish are paramount. Among various casting methods, I have found that permanent mold gravity casting offers a balanced approach for such shell castings, combining good mechanical properties, dimensional accuracy, and cost-effectiveness for medium to high-volume production. This article delves into my detailed analysis and optimization journey for a specific complex aluminum alloy shell casting, highlighting the iterative design process, the incorporation of theoretical models, and practical solutions to overcome defects. Throughout this discussion, I will emphasize the term “shell castings” to underscore their unique characteristics and the tailored approaches needed for their successful manufacture.

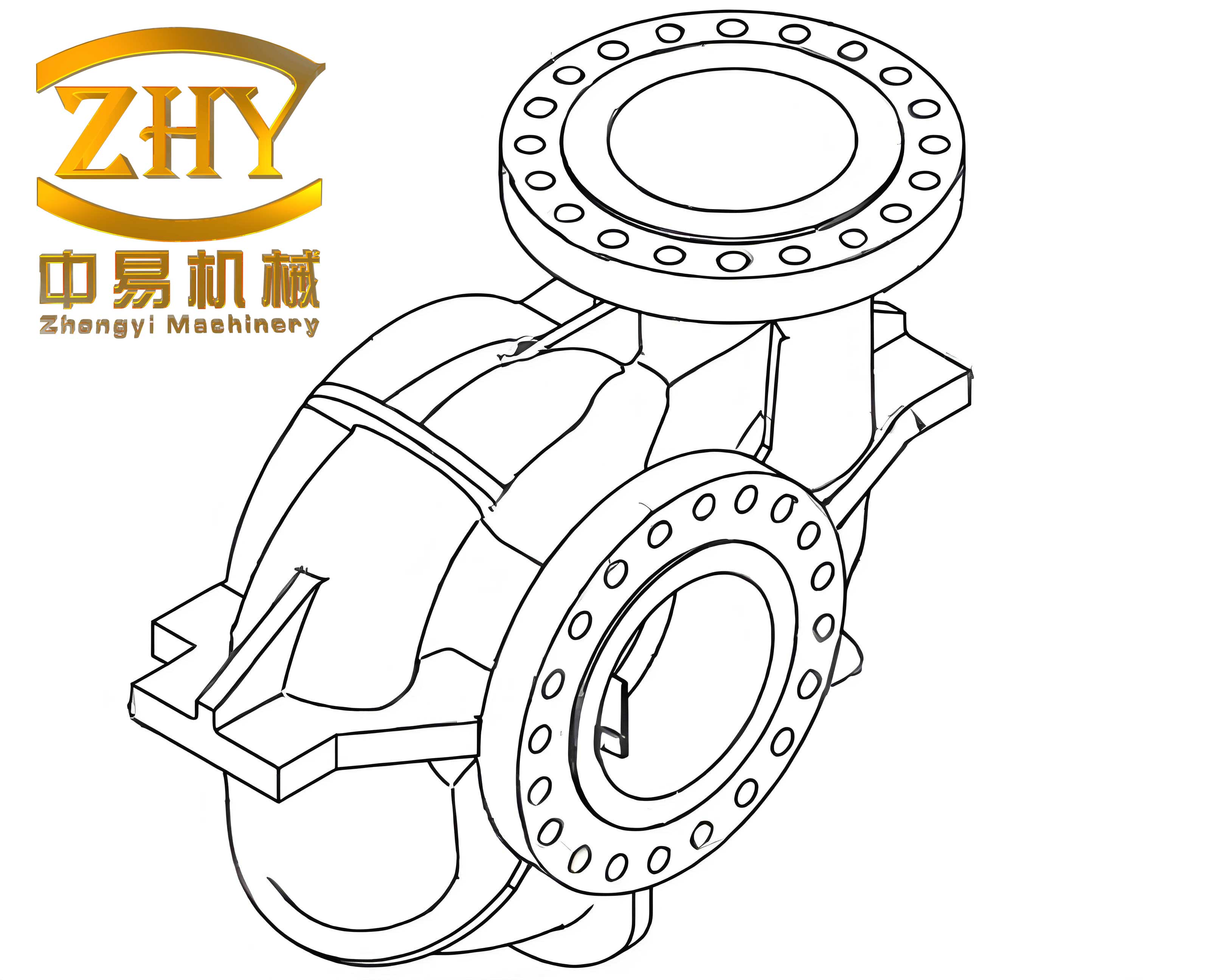

The aluminum alloy shell casting in question features a compact yet complicated structure, with overall dimensions approximately 150 mm x 130 mm x 70 mm. Its wall thickness varies dramatically, from as thin as 3 mm in some sections to as thick as 30 mm in others, creating pronounced thermal gradients during solidification. Additionally, the shell casting includes raised lettering on two faces, with some characters less than 4 mm in height, demanding excellent mold filling and detail replication. The material is an Al-7Si-0.3Mg (A356-type) alloy, a common choice for safety-critical parts due to its good castability and mechanical properties. The key requirements for these shell castings are a uniform, defect-free appearance and a sound internal structure without porosity or shrinkage, which necessitates a meticulous casting process design.

When selecting a casting process for such shell castings, I evaluated several options. Sand casting, while versatile and low-cost, often results in lower surface quality, dimensional accuracy, and mechanical properties, along with environmental concerns from sand handling. Low-pressure casting provides excellent feedability and reduced turbulence, but it requires substantial equipment investment and longer lead times, making it less flexible for rapid iterations. Permanent mold gravity casting, where molten metal is poured into a reusable metal mold under gravity, emerged as the optimal choice. It offers superior mechanical properties (e.g., tensile strength and elongation), finer microstructure, better surface finish (typical roughness Ra 3.2-12.5 µm), and higher dimensional consistency for batch production of shell castings. The table below summarizes my comparative analysis:

| Casting Process | Surface Quality | Dimensional Accuracy | Mechanical Properties | Production Rate | Suitability for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand Casting | Poor to Fair | ±2-3 mm | Lower due to coarse grains | Low to Medium | Limited for high-quality shell castings |

| Permanent Mold Gravity | Good to Excellent | ±0.5-1 mm | High due to rapid cooling | Medium to High | Excellent for complex shell castings |

| Low-Pressure Casting | Excellent | ±0.3-0.8 mm | Very High | Medium | Good but costly for shell castings |

The fundamental challenge in permanent mold gravity casting of shell castings lies in managing solidification to avoid defects. Key principles include directional solidification toward risers, adequate feeding of thick sections, and proper venting to ensure complete filling of thin walls. The solidification time for a section can be estimated using Chvorinov’s rule:

$$t = C \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^2$$

where \( t \) is the solidification time, \( C \) is a mold constant dependent on material and mold properties, \( V \) is the volume of the casting section, and \( A \) is its surface area. For shell castings with varying wall thickness, the modulus \( \frac{V}{A} \) differs significantly, leading to differential cooling rates. Thick sections, with higher modulus, solidify slower and are prone to shrinkage porosity if not properly fed. Thin sections, with lower modulus, solidify quickly and may suffer from misruns or cold shuts if metal flow is insufficient. My initial process design aimed to address these issues for the aluminum alloy shell casting.

My first approach involved a vertical parting mold designed for use on a tilting pouring machine. The shell casting was oriented upright, with the thicker sections placed at the top to promote directional solidification upward toward the risers. The gating system consisted of a top pouring arrangement with a sprue, runners, and gates feeding into the thick regions. The mold was split into left and right halves, with side cores for internal features and a bottom hydraulic core for undercuts. Ejector pins were incorporated in the side molds to facilitate part removal, and vent plugs were placed near thin vertical ribs to aid air escape. The mold material was H13 tool steel, preheated to 250-300°C to reduce thermal shock and improve metal flow. The pouring temperature was set at 710-730°C for the A356 alloy. However, upon trial production, several critical issues emerged specifically for these shell castings:

- Shrinkage Porosity in Thick Sections: The lower thick areas, despite being fed from the top, showed microshrinkage due to inadequate thermal gradients. The feeding distance from the riser was too long, violating the requirement for progressive solidification.

- Misruns in Thin Ribs: The thin vertical ribs on the sides, with 3 mm thickness, often failed to fill completely, resulting in incomplete shell castings.

- Cold Shuts at Remote Areas: The farthest points from the gate, especially where wall thickness was 3 mm, exhibited cold shuts due to premature freezing of the metal stream.

- Ejection and Surface Defects: The ejector pins left visible marks on the casting surface, and the small draft angles on the internal cores caused sticking and scoring during ejection, damaging the shell castings.

- Venting Limitations: Even with vent plugs, air entrapment in complex corners led to gas porosity and worsened misruns.

To diagnose these problems quantitatively, I applied fluid flow and heat transfer analyses. The Reynolds number for the flow in thin sections can be expressed as:

$$Re = \frac{\rho v D_h}{\mu}$$

where \( \rho \) is the metal density (~2400 kg/m³ for A356), \( v \) is the flow velocity, \( D_h \) is the hydraulic diameter, and \( \mu \) is the dynamic viscosity (~0.0013 Pa·s at pouring temperature). For a 3 mm thick section, \( D_h \) is small, leading to high \( Re \) and potential turbulence if velocity is high, but if velocity is too low, the metal freezes before filling. The critical filling time \( t_f \) to avoid cold shuts can be approximated by:

$$t_f = \frac{T_{pour} – T_{liquidus}}{dT/dt}$$

where \( T_{pour} \) is the pouring temperature, \( T_{liquidus} \) is the liquidus temperature (~615°C for A356), and \( dT/dt \) is the cooling rate. For thin walls, \( dT/dt \) is high, requiring faster filling. My initial gating design did not provide sufficient velocity for the thin ribs. Additionally, the feeding capability for shrinkage compensation is governed by the Niyama criterion, often used in simulation, which relates temperature gradient \( G \), cooling rate \( R \), and a critical value to predict porosity. For the thick sections, \( G \) was insufficient due to the mold geometry.

My initial modifications focused on adjusting process parameters and minor mold changes. I increased the pouring temperature to 740°C to enhance fluidity, and redesigned the gating to increase metal velocity in thin sections by reducing gate cross-sectional area. I added more vent plugs along the ribs and incorporated a sand core at the parting line to create a feeding channel from the riser to the lower thick section, improving thermal gradients. These changes partially alleviated the shrinkage and misrun issues, but the surface defects from ejector pins and core sticking persisted. The table below summarizes the initial trial results and the effect of these adjustments:

| Defect Type | Initial Severity (Scale 1-5) | After Parameter Adjustment | Remaining Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrinkage Porosity | 4 (High) | Reduced to 2 (Moderate) | Still present in isolated hot spots |

| Misruns in Thin Ribs | 5 (Very High) | Reduced to 2 (Moderate) | Occasional incomplete filling |

| Cold Shuts | 3 (Medium) | Reduced to 1 (Low) | Minimal |

| Surface Marks from Ejectors | 4 (High) | No improvement | Persistent, affecting shell casting appearance |

| Core Sticking and Damage | 4 (High) | No improvement | Still causing scrap |

Recognizing that incremental changes were insufficient, I undertook a comprehensive redesign of the mold and process. The core idea was to switch from a machine-operated mold to a hand-operated mold, which granted greater flexibility in parting line selection, core design, and ejection method. For these shell castings, I reoriented the casting to a horizontal position, placing the thin ribs at the bottom to take advantage of gravity-assisted filling. The risers were relocated to the side of the shell casting, adjacent to the thickest sections, to shorten feeding distances and ensure directional solidification from the thin zones toward the risers. To address the internal core sticking, I replaced the metal retractable core with a resin-coated sand (覆膜砂) core. This sand core, made from fine silica sand with a phenolic resin coating, can form complex internal shapes with excellent surface finish and is easily removed after casting by mechanical knockout or thermal decomposition. The sand core was positioned using pins in the mold halves, eliminating the need for hydraulic actuators.

The new mold design featured a split along the mid-plane of the ribs, incorporating loose pieces (side pulls) for undercuts and the raised lettering. The loose pieces were designed with draft angles and backside relief to reduce heat accumulation and improve cooling. Venting was achieved through natural gaps at parting lines and dedicated vents in the loose pieces, avoiding the use of vent plugs that could leave marks. No ejector pins were used; instead, the shell castings were removed manually by extracting the loose pieces first. The gating system was a tapered sprue with multiple ingates feeding from the side riser to ensure uniform filling. The mold temperature was carefully controlled using heating cartridges and cooling channels to maintain a gradient from bottom (cooler) to top (warmer), further promoting directional solidification. The key dimensions and parameters are listed below:

| Parameter | Initial Design | Optimized Design |

|---|---|---|

| Casting Orientation | Vertical | Horizontal |

| Parting Line | Vertical split | Horizontal split with loose pieces |

| Riser Location | Top | Side, near thick sections |

| Internal Core | Metal retractable core | Resin-coated sand core |

| Ejection Method | Ejector pins | Manual removal via loose pieces |

| Venting | Vent plugs | Parting line vents and loose piece gaps |

| Mold Temperature Gradient | Uniform (~250°C) | Bottom: 200°C, Top: 300°C |

| Pouring Temperature | 710-730°C | 720-740°C |

The theoretical basis for this optimized design involves several principles. The feeding distance \( L_f \) for a riser can be estimated using empirical formulas for aluminum alloys. For plate-like sections, a common relation is:

$$L_f = k \sqrt{t}$$

where \( t \) is the plate thickness and \( k \) is a constant (typically 4-6 for aluminum in metal molds). By placing risers on the side close to thick areas, \( L_f \) becomes adequate to feed the entire thick zone. For the thin ribs at the bottom, the pressure head from the sprue height \( h \) provides additional driving force for filling, according to Bernoulli’s principle:

$$v = \sqrt{2gh}$$

where \( g \) is gravity and \( h \) is the effective head height. With horizontal orientation, \( h \) is maximized for the bottom sections, enhancing fillability. The use of a sand core improves dimensional accuracy and surface finish for internal features of shell castings, as sand can replicate fine details without the friction issues of metal cores. The thermal properties of the sand core also moderate cooling rates, reducing hot tearing tendencies. The solidification sequence is now controlled to be directional from the thin bottom ribs (which cool fastest) upward toward the side risers, ensuring that liquid metal is available to compensate for shrinkage in thick sections. The Niyama criterion parameter \( NY \) is given by:

$$NY = \frac{G}{\sqrt{R}}$$

where \( G \) is the temperature gradient and \( R \) is the cooling rate. In the optimized design, \( G \) is increased by the mold temperature gradient, and \( R \) is balanced by the sand core, leading to \( NY \) values above the critical threshold (e.g., >1 °C¹/² s¹/²) to prevent microporosity.

After implementing the optimized design, trial productions of the shell castings were conducted. The results were markedly improved. Visual inspection revealed complete filling of all thin ribs and lettering, with no cold shuts or misruns. Radiographic and ultrasonic testing confirmed the absence of shrinkage porosity in thick sections. The surface finish was uniform without ejector marks or scoring, meeting the aesthetic requirements for shell castings. The sand cores were easily removed, leaving clean internal surfaces. Mechanical testing of samples from the shell castings showed tensile strengths of 220-240 MPa and elongation of 6-8%, consistent with A356-T6 specifications. The yield was also improved due to reduced scrap. The following table quantifies the improvements:

| Quality Metric | Initial Design Performance | Optimized Design Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fill Completeness (Thin Ribs) | 70% (often incomplete) | 100% (fully filled) | +30% |

| Shrinkage Defects (Thick Sections) | Defects present in 40% of castings | Defects absent in 95% of castings | +55% |

| Surface Finish (Ra, µm) | 6.3-12.5 with marks | 3.2-6.3 uniform | ~50% smoother |

| Dimensional Accuracy (vs. CAD) | ±0.8 mm | ±0.3 mm | +0.5 mm precision |

| Casting Yield (Good parts) | 60% | 90% | +30% |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 200-220 | 220-240 | +10% |

The success of this optimization can be further analyzed through thermal modeling. The temperature distribution during solidification can be described by the heat conduction equation:

$$\frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T$$

where \( \alpha \) is the thermal diffusivity of the alloy. For the shell casting in the horizontal mold, boundary conditions vary: the bottom mold interface has higher heat extraction (due to cooler mold), while the top riser area has lower extraction. This creates a favorable temperature gradient. The solid fraction \( f_s \) evolution can be approximated using the Scheil equation for non-equilibrium solidification:

$$f_s = 1 – \left( \frac{T_m – T}{T_m – T_l} \right)^{\frac{1}{k-1}}$$

where \( T_m \) is the melting point of pure aluminum, \( T_l \) is the liquidus temperature, and \( k \) is the partition coefficient. In practice, for A356, the solidification range is about 40°C, and the optimized design ensures that mushy zone progression is directional toward the riser. The feeding pressure \( P_f \) available from the riser is given by:

$$P_f = \rho g h_r – \Delta P_{loss}$$

where \( h_r \) is the riser height and \( \Delta P_{loss} \) accounts for frictional losses in the feeding channels. With side risers placed high, \( h_r \) is adequate to overcome losses and feed shrinkage until solidification is complete.

Beyond this specific case, the lessons learned have broader implications for permanent mold gravity casting of complex shell castings. Key takeaways include the importance of orientation to leverage gravity for thin-wall filling, the strategic use of sand cores to replace complex metal cores, and the benefits of hand-operated molds for flexibility in ejection and parting. For future shell castings with similar challenges, I recommend a structured approach: start with solidification simulation to predict hot spots and fill patterns, prototype with adjustable mold components, and iterate based on empirical data. The integration of real-time process monitoring, such as thermocouples in the mold and flow sensors, could further enhance quality control for shell castings.

In summary, the journey from an initial defective design to a robust optimized process for aluminum alloy shell castings underscores the iterative nature of casting engineering. By combining fundamental principles of fluid dynamics and heat transfer with practical mold design innovations, I achieved shell castings that meet stringent quality standards. The optimized permanent mold gravity casting process, featuring horizontal orientation, side risers, and resin-coated sand cores, proves highly effective for complex shell castings with varying wall thicknesses. This methodology can be adapted to other alloy systems and geometries, contributing to the advancement of reliable manufacturing for critical shell castings in various industries.