In the production of aluminum alloy castings, the formation of porosity remains one of the most persistent and detrimental defects encountered. The inherent tendency of aluminum alloys to oxidize and absorb gases during melting and pouring directly conflicts with the demand for high-integrity, high-performance components. The issue of porosity in casting is not merely a technical nuisance; it is a critical factor determining the structural reliability, mechanical performance, and overall quality of cast parts used in aerospace, automotive, and countless other industries. My experience in foundry practice has consistently shown that understanding and controlling porosity in casting is paramount. This article synthesizes practical knowledge and theoretical principles to explore the categories, formation mechanisms, detrimental effects, and, most importantly, the comprehensive preventive measures for porosity in casting aluminum alloys.

1. Definition and Classification of Porosity

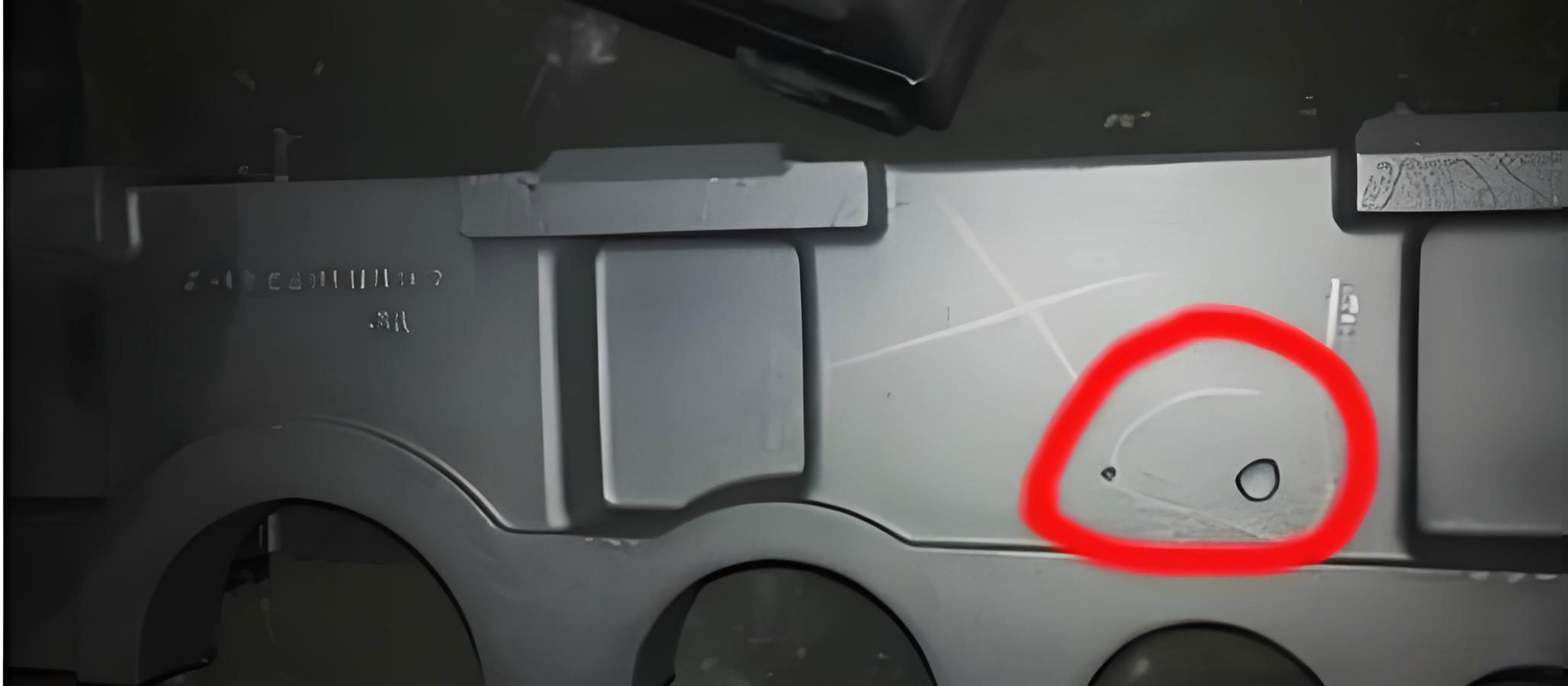

Porosity in casting refers to cavities or voids within the solidified metal caused by trapped gas. In aluminum alloys, the most prevalent form is hydrogen porosity, often manifesting as “pinholes.” Pinholes are typically defined as dispersed gas pores smaller than 1 mm in diameter, frequently appearing round and distributed unevenly throughout the casting cross-section, particularly in thick sections and areas of slow cooling. Based on their distribution and morphology observed in macro-examination, pinhole porosity in casting can be classified into three distinct types:

| Type | Macrostructure Characteristics | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|

| Point Pinholes | Round, discrete dots. | Clear contours, pores are not connected. Number of pores per unit area and their diameter can be measured. |

| Reticular Pinholes | Dense, interconnected network of pores. | Forms a mesh-like structure with some larger cavities. Difficult to count pores or measure individual diameters. |

| Comprehensive Pinholes | Intermediate form. | Larger, often polygonal pores mixed with smaller ones, bridging the characteristics of point and reticular types. |

2. Mechanism of Porosity Formation

The primary cause of porosity in casting aluminum alloys is the precipitation of dissolved hydrogen during solidification. Hydrogen is the only gas with significant solubility in molten aluminum, and this solubility changes dramatically with temperature.

The relationship between hydrogen solubility and temperature is fundamental. The solubility increases with rising temperature and decreases sharply upon solidification. The solubility of hydrogen in pure aluminum can be described empirically. Upon solidification, the solubility can drop by a factor of nearly 20, forcing the excess hydrogen to nucleate and form bubbles. If these bubbles cannot float to the surface and escape, they become trapped as permanent porosity in casting.

$$ C_{H} = k \sqrt{P_{H_2}} \cdot e^{(-\frac{\Delta H}{2RT})} $$

Where \( C_{H} \) is the dissolved hydrogen concentration, \( k \) is a constant, \( P_{H_2} \) is the partial pressure of hydrogen at the melt surface, \( \Delta H \) is the heat of solution, \( R \) is the gas constant, and \( T \) is the absolute temperature. This shows that both the environmental conditions (affecting \( P_{H_2} \)) and melt temperature critically control hydrogen pickup.

The main source of hydrogen is the reaction between molten aluminum and water vapor. This can originate from humid air, damp charge materials, moisture in refractories, or combustion products. The primary reaction is:

$$ 2Al_{(l)} + 3H_2O_{(v)} \rightarrow Al_2O_{3(s)} + 6[H]_{(in\ Al)} $$

For alloys containing magnesium, an even more vigorous reaction occurs, making them particularly susceptible to porosity in casting:

$$ Mg_{(in\ Al)} + H_2O_{(v)} \rightarrow MgO_{(s)} + 2[H]_{(in\ Al)} $$

The dissolved atomic hydrogen ([H]) then diffuses into the melt. During solidification, especially in alloys with wide freezing ranges, dendritic networks can isolate small pools of liquid. The hydrogen rejected from the solidifying metal enriches these last-to-freeze pools, leading to high local supersaturation and pore nucleation, often on oxide bifilms or other inclusions which act as favorable sites.

| State | Temperature (°C) | Approx. Solubility (ml/100g Al) |

|---|---|---|

| Solid | 500 | ~0.05 |

| At Melting Point (Liquid) | 660 | ~0.7 |

| Liquid | 800 | ~1.8 |

3. Key Factors Influencing Porosity Formation

Several factors directly influence the severity of porosity in casting. Control over these factors is the first line of defense.

| Factor | Mechanism of Influence | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Raw & Auxiliary Materials | Introduce moisture, grease, or hydrated oxides that decompose into water vapor. | All charge materials, fluxes, and coatings must be clean and dry. Pre-heat to >250°C to drive off moisture. |

| Melting Equipment & Tools | New or damp refractories, crucibles, and tools release moisture into the melt environment. | New linings/crucibles require prolonged baking. All tools must be preheated and coated before contact with molten metal. |

| Ambient Humidity | Increases the partial pressure of water vapor (\(P_{H_2O}\)) in the furnace atmosphere. | Extra vigilance and stricter drying protocols are necessary during rainy/humid seasons to minimize porosity in casting. |

| Melting Practice | High superheat temperatures and prolonged holding times increase hydrogen solubility and diffusion. | Melt quickly at the lowest practical temperature (typically <750°C). Minimize hold time after melting. |

| Mold Condition (Sand) | Wet sand molds generate large volumes of steam, which can penetrate the metal, causing gross porosity. | Use dry or skin-dried molds. For green sand, maintain moisture content below 5%. |

| Mold Design (Permanent Mold) | Non-permeable metal molds trap air and gases, creating back-pressure and gas entrapment. | Incorporate strategic vents, vent plugs, and parting line gaps to allow gases to escape. |

4. Impact of Porosity on Casting Properties

The presence of porosity in casting acts as internal stress raisers and reduces the effective load-bearing cross-sectional area. This leads to a direct and measurable degradation of mechanical properties. The relationship is often linear: as the severity of porosity increases, tensile strength and elongation decrease. Studies correlating standardized pinhole grades with mechanical test data confirm this trend. For common casting alloys like those in the Al-Si and Al-Cu systems, each increase in pinhole grade can result in an approximate reduction of 3% in tensile strength and a more significant reduction of about 5% in elongation. This underscores why controlling porosity in casting is not optional for structural components.

| Pinhole Grade | Tensile Strength (MPa) Range | Average Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) Range | Average Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Least) | 280 – 310 | 295 | 6.0 – 8.5 | 7.2 |

| 2 | 270 – 300 | 285 | 5.0 – 7.5 | 6.3 |

| 3 | 260 – 290 | 275 | 4.0 – 6.5 | 5.4 |

| 4 (Most) | 250 – 280 | 265 | 3.5 – 5.5 | 4.5 |

5. Strategic Prevention of Porosity

Combating porosity in casting requires a systematic, multi-pronged approach focused on prevention (“Keep it out”), removal (“Get it out”), and suppression (“Keep it in solution”). The overarching principle is “Prevention first, assisted by removal.”

5.1 Foundational Preparations (“Prevention”)

This step addresses the factors in Table 3. It is the most critical line of defense against porosity in casting.

- Charge Preparation: All ingots, returns, and alloying elements must be clean, free of rust, oil, and moisture. Pre-heating to 300-450°C for several hours is essential to drive off adsorbed water.

- Equipment Conditioning: New or repaired furnaces, crucibles, and ladles must undergo a controlled baking cycle (e.g., heating to 700-800°C for several hours) to remove chemical and adsorbed water from refractories.

- Tool Preparation: Skimmers, degassing lances, and transfer ladles must be thoroughly preheated (to at least 200°C) and often coated with a protective wash to prevent introducing moisture and iron pickup.

5.2 Controlled Melting Practice

Operational discipline during melting directly affects hydrogen absorption.

- Melt rapidly at the lowest temperature sufficient for alloying and treatment (usually 700-750°C). Avoid excessive superheating.

- Minimize the total melt cycle time—the “melt-to-pour” time. Prolonged holding, especially above the melt point, allows continuous hydrogen diffusion into the bath.

- Protect the melt surface with a suitable cover flux to create a barrier against furnace atmosphere moisture, especially for magnesium-containing alloys.

5.3 Active Melt Degassing and Refining (“Removal”)

Despite best preventive efforts, some hydrogen pickup is inevitable. Active degassing is therefore a standard and essential step to reduce hydrogen to acceptable levels and minimize porosity in casting. The principle is to introduce a purging gas (or a gas-generating compound) into the melt. Bubbles of the inert gas (e.g., Argon, Nitrogen) or reactive gas (e.g., Chlorine from C2Cl6) rise through the melt. Since the partial pressure of hydrogen inside these bubbles is essentially zero, dissolved hydrogen diffuses into the bubbles according to Sieverts’ Law and is removed as the bubbles escape to the surface. Effective degassing also aids in the flotation and removal of non-metallic inclusions.

$$ [H]_{(in\ Al)} \rightleftharpoons \frac{1}{2} H_{2(gas\ bubble)} $$

Common degassing methods and agents include rotary degassing with Argon/N2, tablet degassers (e.g., hexachloroethane, C2Cl6), and lance injection of chlorine-nitrogen mixtures.

| Agent | Typical Addition (% of Melt Wt.) | Process Temperature (°C) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Argon / Nitrogen (Rotary) | N/A (Gas flow) | 700 – 750 | Most effective with a rotating impeller creating fine bubbles. Environmentally friendly. |

| Hexachloroethane (C2Cl6) | 0.2 – 0.6 | 700 – 730 | Generates Cl2 and C2Cl4 gas. Very effective but produces toxic fumes. Requires fume extraction. |

| Chlorine-Nitrogen Mixture | N/A (Gas flow, e.g., 10% Cl2) | 700 – 750 | Highly efficient. Chlorine reacts to form HCl gas, enhancing hydrogen removal. Requires strict safety controls. |

| “Eco-friendly” Salt Tablets | 0.3 – 0.8 | 720 – 750 | Formulations without C2Cl6, often based on carbonate reactions. Lower fume toxicity but may be less potent. |

Following degassing, a quiet holding period (e.g., 5-15 minutes) is crucial to allow remaining bubbles and floated inclusions to rise to the surface for skimming.

5.4 Mold Design for Gas Escape

This is critical for permanent mold (metal die) casting, where the mold itself is non-permeable. Strategic venting must be designed into the tooling to prevent the entrapment of air and core gases, which would lead to blister-type porosity in casting.

- Parting Line Vents: Shallow vents (0.10-0.15 mm deep) machined along the die parting line allow air to escape while preventing metal flash.

- Vent Plugs (Vent Pins): Small sintered metal plugs or pins installed in the die at high points or “air-pocket” locations. They allow gas to pass but block molten metal.

- Overflows and Vents: Strategically placed overflows at the end of fill pathways help to vent air and contain cold metal.

- Vacuum Assistance: Applying a vacuum to the mold cavity before and during filling actively extracts air and gases, significantly reducing gas-related defects.

5.5 Solidification Control (“Suppression”)

While not a primary removal technique, controlling solidification can influence pore formation. Rapid solidification under pressure (e.g., in high-pressure die casting) increases the solubility of hydrogen and reduces the time for bubble nucleation and growth, effectively suppressing the appearance of porosity in casting. The application of an isostatic pressure during solidification can also force dissolved gas to remain in solution or shrink the size of any pores formed.

6. Conclusion

The battle against porosity in casting aluminum alloys is won through meticulous attention to detail at every stage of the process. It requires a deep understanding that the problem originates long before the metal is poured—in the condition of the materials, the design of the equipment, and the control of the melting environment. A successful strategy is built on the triad of Prevention, Removal, and Control. By rigorously preventing hydrogen and moisture ingress through proper material handling and furnace management, actively removing absorbed hydrogen via proven degassing techniques, and controlling mold filling and solidification to aid gas escape, the incidence and severity of porosity in casting can be minimized to levels that meet the most demanding specifications. Ultimately, achieving consistently sound castings is a testament to a foundry’s commitment to integrating scientific principle with disciplined, skilled practice. The pursuit of zero-defect castings may be asymptotic, but through systematic application of these strategies, we can come exceedingly close, ensuring the performance and reliability that modern applications demand.