In my extensive experience with die casting production, I have consistently observed that porosity in casting defects, arising from gas entrapment within the molten alloy, severely compromises the quality and machinability of cast components. Almost all components produced by conventional die casting methods exhibit defects caused by gases, making it challenging to achieve high-quality products for parts requiring airtightness or intended for high-temperature environments using standard equipment. The issue of porosity in casting, particularly flat or slit-like pores embedded within the wall of a casting, not only undermines mechanical strength but also leads to deformation and surface blistering when the entrapped high-pressure gas expands upon heating in elevated temperature conditions. This article, based on practical production insights, aims to explore the mechanisms behind porosity in casting defects and proposes methods to minimize them using ordinary die casting machines, catering to general product requirements without the need for complex ancillary systems like vacuum die casting or advanced techniques such as “Acurad” die casting.

The formation of porosity in casting defects is primarily attributed to gas entrainment during the die casting process. Gas can be introduced from various sources, including the shot sleeve, runner system, and residual air in the mold cavity, becoming trapped within the molten alloy as it fills the cavity under high speed and pressure. Upon solidification under intensification pressure, these entrapped gases are compressed and retained within the casting, leading to diverse defect morphologies. I categorize these defects into three main types based on their characteristics and formation mechanisms: porosity-shrinkage complexes, dispersed porosity, and flat or slit-like porosity. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective preventive strategies.

The first type, porosity-shrinkage complexes, typically occurs in thick sections or hot spots远离 the gate. Here, gas entrained during filling becomes encapsulated in regions where solidification is slowest. As the alloy solidifies rapidly in thin sections and at the gate, the intensification pressure from the shot cylinder may not effectively transmit to these hot spots. The slower solidification in hot spots allows for shrinkage cavities to form due to inadequate feeding, and adjacent entrapped gas bubbles can merge with these cavities under specific conditions. The heat released during solidification in a hot spot can be approximated by:

$$ Q = \rho \cdot V \cdot [L + c_p (T_p – T_s)] $$

where \( Q \) is the heat released, \( \rho \) is the alloy density, \( V \) is the volume of the solidifying region, \( L \) is the latent heat of fusion, \( c_p \) is the specific heat of the liquid alloy, \( T_p \) is the pouring temperature, and \( T_s \) is the solidus temperature. This equation indicates that larger hot spot volumes release more heat, prolonging solidification time and promoting shrinkage. When a high-pressure gas bubble is near a shrinkage cavity, it may penetrate into the cavity if the gas pressure \( P_g \) exceeds the sum of the pressure in the shrinkage cavity and the strength of the intervening alloy, i.e., \( P_g \geq \Sigma \). This results in a combined defect with a smooth, bright inner wall on the gas side and an irregular surface on the shrinkage side, significantly weakening the component.

The second type, dispersed porosity, manifests as small, irregularly distributed pores—round, elliptical, or cluster-like—within the casting wall. This porosity in casting arises when gas is dispersed into the molten alloy during turbulent filling, especially under conditions like “spray” flow where the alloy fragments into droplets, entrapping air. Although these pores are small and may not drastically affect mechanical strength initially, they can cause surface blistering or “popcorning” when the casting is heated, as the compressed gas expands. The behavior of these gas bubbles can be described by the gas law. For an ideal gas under constant temperature:

$$ P \cdot V = \text{constant} $$

where \( P \) is the gas pressure and \( V \) is the bubble volume. During die casting, entrapped gas is compressed to small volumes under high intensification pressure. However, if the pressure is insufficient, larger pores form. When the casting is exposed to elevated temperatures, the gas expands according to:

$$ \frac{P_1 V_1}{T_1} = \frac{P_2 V_2}{T_2} $$

where subscripts 1 and 2 denote initial and final states. For aluminum alloy castings, temperatures above 100°C can initiate blistering, and at 200°C or higher, internal pores may expand significantly, creating a spongy structure that becomes apparent after machining, adversely affecting appearance and polishability.

The third type, flat or slit-like porosity, is particularly detrimental, appearing as thin, elongated seams that split the casting wall, with smooth, shiny interfaces. This porosity in casting results from massive gas entrainment, often due to high shot speeds and thin gates that promote “spray” filling. In such cases, the molten alloy rapidly forms an incomplete “shell” along the mold wall, blocking venting paths and trapping gas from the shot sleeve and runners within this shell. Under high intensification pressure, the entrapped gas is compressed into a flat, film-like shape that separates the metal matrix. In laminar flow within the runner or cavity, gas bubbles tend to migrate toward the center of the stream due to velocity gradients, as described by:

$$ v_{\text{max}} = \text{maximum velocity at center}, \quad v_{\text{min}} = \text{minimum velocity at wall} $$

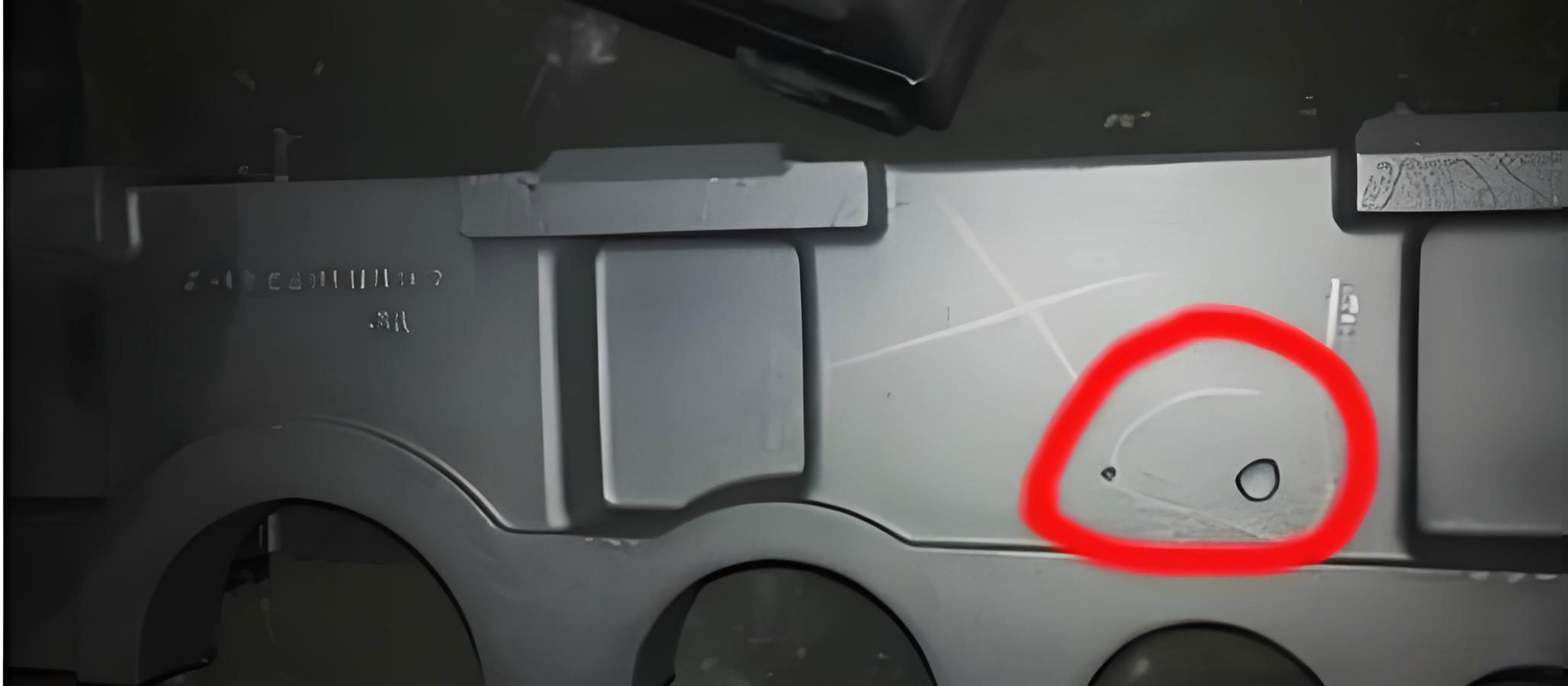

This leads to gas accumulation along flow lines. In production, I have observed such slit-like porosity not only in casting walls but also in runners and biscuit remnants. For instance, in horizontal cold-chamber die casting, layers of gas can separate the biscuit and runner, extending into the gate area. Vertical die casting machines generally introduce less gas from the shot sleeve, but improper operation can still cause similar issues. Moreover, low shot sleeve fill ratios and high injection speeds exacerbate this form of porosity in casting. In dead zones of the mold cavity where venting is poor, gas compressed by converging metal streams can create laminar defects resembling cold shuts, with smooth internal surfaces that severely compromise strength.

To address these issues of porosity in casting, preventive measures must focus on controlling gas entrainment and reducing gas content in the alloy. Based on my practice, I recommend the following approaches, which can be implemented on conventional die casting machines.

First, strict adherence to melting and handling procedures is essential to minimize gas introduction. This includes storing raw materials in dry conditions to prevent moisture absorption, which increases hydrogen content in molten aluminum. All tools contacting the alloy should be preheated to avoid moisture vaporization. Melting temperature must be controlled, as higher temperatures accelerate gas diffusion into the alloy, raising gas content. Even after degassing, prolonged holding time can increase gas pickup. Degassing agents should be dried before use to prevent additional gas sources. These steps directly reduce the likelihood of porosity in casting.

Second, casting design should be optimized to mitigate porosity in casting. Uniform wall thickness avoids hot spots that promote shrinkage and gas entrapment. Where thick sections are unavoidable, incorporating cores or holes can enhance heat dissipation and provide venting through core clearances. Additionally, design modifications should improve filling conditions and pressure transmission to hot spots, extending the duration of intensification pressure.

Third, appropriate mold coatings are crucial. Coatings should have low volatile gas content and low evaporation temperatures, applied evenly to prevent gas entrapment from coating vapors. Excessive or improper coating can contribute to porosity in casting by introducing gases into the alloy stream.

Fourth, effective venting systems are vital. Deep cavities and dead zones should utilize inserts, cores, ejector pins, or dedicated vents to allow gas escape. The parting line should be selected not only for part ejection but also for optimal venting. Gate location and size should avoid early blockage of vents and prevent turbulent flow that entraps gas. Runner and gate design should ensure intensification pressure reaches hot spots. Vents should be placed where gas is likely to accumulate, such as at metal flow convergence points or last-to-fill areas. A summary of venting strategies is presented in Table 1.

| Venting Strategy | Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Parting Line Vents | Allow gas escape from main cavity | Machined slots at parting line |

| Core and Ejector Pin Clearances | Vent deep sections and dead zones | Utilize existing gaps around moving components |

| Overflow Wells | Collect gas and cold metal at flow ends | Pockets connected to cavity |

| Vacuum Venting (if feasible) | Evacuate gas before filling | Integrated vacuum systems |

Fifth, process parameters must be carefully selected. The shot sleeve diameter should ensure a fill ratio greater than 50% to reduce air entrapment. Injection speed should be minimized to promote laminar flow and reduce turbulence, thereby decreasing gas entrainment. Within machine clamping force limits, higher specific pressure (intensification pressure) should be used to compress entrapped gas to smaller volumes. Lower pouring temperatures and thicker gates can also help, as they reduce flow velocity and promote sequential filling, while thicker gates prolong pressure application. Mold temperature plays a role too; low mold temperatures may hinder coating evaporation, leading to gas entrapment. Regular mold maintenance, such as cleaning vents clogged by coatings, and ensuring proper clearance between shot sleeve and plunger, are essential practices. Table 2 summarizes key process parameters for minimizing porosity in casting.

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Effect on Porosity |

|---|---|---|

| Shot Sleeve Fill Ratio | > 50% | Reduces air volume in sleeve |

| Injection Speed | Low to moderate | Promotes laminar flow, reduces gas entrainment |

| Specific Pressure | High (within machine limits) | Compresses entrapped gas, minimizes pore size |

| Pouring Temperature | Lower end of range | Reduces gas solubility and turbulence |

| Gate Thickness | Relatively thick | Enhances pressure transmission and feeding |

| Mold Temperature | Moderate (e.g., 150-200°C for Al) | Ensures coating evaporation and reduces thermal shock |

In die casting, solidification occurs under high pressure, which generally suppresses gas evolution from dissolved sources except in thick centers or areas where pressure transmission is inadequate. Therefore, porosity in casting defects predominantly stems from mechanically entrapped gas during filling. Preventive measures should thus prioritize optimizing mold design and process conditions to minimize gas entrainment and enhance venting. From my experience, implementing these strategies on ordinary die casting machines can significantly reduce porosity in casting, yielding components with improved integrity for general applications. Continuous monitoring and adjustment based on specific part geometry and production conditions are key to managing this pervasive issue. The comprehensive approach outlined here, combining metallurgical control, design optimization, and process refinement, provides a practical framework for addressing porosity in casting in aluminum alloy die casting operations.

To further illustrate the impact of process variables, consider the relationship between injection parameters and gas entrapment. The energy dynamics during filling can be analyzed using fluid mechanics principles. For instance, the Reynolds number \( Re = \frac{\rho v D}{\mu} \), where \( \rho \) is density, \( v \) is velocity, \( D \) is hydraulic diameter, and \( \mu \) is viscosity, indicates flow regime; high \( Re \) promotes turbulence and gas entrainment. Minimizing \( v \) through slower injection reduces \( Re \), fostering laminar flow and less porosity in casting. Additionally, the pressure drop \( \Delta P \) in the gating system can be estimated using Bernoulli’s equation with losses:

$$ \Delta P = \frac{1}{2} \rho v^2 \left( f \frac{L}{D} + K \right) $$

where \( f \) is friction factor, \( L \) is length, and \( K \) is loss coefficient. Optimizing runner geometry to reduce \( \Delta P \) ensures adequate pressure for gas compression. Moreover, the solidification time \( t_s \) for a section can be approximated by Chvorinov’s rule:

$$ t_s = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where \( B \) is a mold constant, \( V \) is volume, \( A \) is surface area, and \( n \) is an exponent (typically ~2). Hot spots with high \( V/A \) ratios solidify slowly, increasing shrinkage and gas pore formation risk. Design modifications to increase \( A \) (e.g., adding ribs or cores) can mitigate this. These theoretical insights complement empirical practices in controlling porosity in casting.

In summary, porosity in casting is a multifaceted defect influenced by material, design, and process factors. Through systematic application of the measures discussed—ranging from alloy preparation to parameter tuning—I have achieved notable reductions in defect rates. The key is to view porosity in casting not as an inevitable byproduct but as a manageable challenge that demands a holistic, evidence-based approach. By prioritizing gas control and venting efficiency, even conventional die casting setups can produce components with acceptable levels of porosity in casting for many industrial applications, paving the way for enhanced product performance and reliability.