The persistent challenge of porosity in casting remains a critical factor affecting the structural integrity, mechanical performance, and economic viability of metal components. My extensive work in foundry technology has consistently brought me face-to-face with this defect, particularly when employing modern binder systems like alkaline phenolic no-bake resin sand. While this environmentally favorable sand offers advantages such as low nitrogen content and reduced gas evolution compared to other resins, it does not render castings immune to the formation of pores. The genesis of porosity in casting is seldom attributable to a single cause; rather, it is typically the culmination of complex interactions between mold materials, metal chemistry, and process parameters. In this detailed exploration, I will dissect the mechanisms behind pore formation, present a comprehensive analytical framework, and systematically outline proven mitigation strategies, with particular emphasis on steel castings produced in alkaline phenolic resin sand molds.

1. Fundamental Mechanisms of Gas Porosity Formation

The entrapment of gas within a solidifying metal matrix manifests as porosity in casting. This defect can be fundamentally categorized based on the source and formation mechanism of the gas. Understanding these categories is the first step towards effective prevention.

1.1 Invasive (or External) Porosity

This is the most common type of porosity in casting associated with organic sand binders. Gas is generated from external sources—the mold or core—and subsequently invades the liquid metal. The primary sources are:

- Decomposition of Organic Binders: Resins, catalysts, and other additives thermally decompose upon contact with molten metal, releasing significant volumes of gas (e.g., H₂, CO, CO₂, hydrocarbons).

- Moisture: Even low levels of moisture in the sand, coatings, or atmospheric condensation can vaporize instantly, creating high-pressure steam.

- Inadequate Permeability/Purging: If the mold and core lack sufficient permeability or effective venting pathways, the generated gases cannot escape quickly enough to the atmosphere. The resulting pressure build-up at the metal-mold interface can force gas into the metal stream or the solidifying skin.

The pressure balance at the interface is crucial. Gas will invade the metal when the local gas pressure ($P_{gas}$) exceeds the sum of the metallostatic pressure ($P_{metal}$) and the pressure required to form a bubble nucleus against surface tension ($P_{σ}$). This can be expressed as a condition for invasion:

$$ P_{gas} > P_{metal} + P_{σ} $$

Where $P_{metal} = ρ g h$, with $ρ$ being the metal density, $g$ gravity, and $h$ the ferrostatic head height above the point in question. Invasive pores are often characterized by a smooth, shiny interior and a spherical or elongated “pear-shaped” morphology, typically located near the mold surface or in upper sections of the casting.

1.2 Reactive (or Endogenous) Porosity

This form of porosity in casting originates from chemical reactions within the molten metal itself or at the metal-mold interface. Common reactions include:

- Metal-Mold Reaction: For steel castings, moisture or compounds in the mold can react with elements like carbon (C) to form gas (e.g., $C + H_2O \rightarrow CO + H_2$). Alkaline phenolic resins are generally more resistant to such reactions than acid-catalyzed resins, but the risk persists if coatings are inadequate or sand conditions are poor.

- Deoxidation Products: In steel melting, inadequate or improper deoxidation can leave dissolved oxygen in the melt. During solidification, this oxygen may react with carbon (carbon boil) to form CO gas bubbles, which become trapped. This is often linked to slag or inclusion formation as well.

Reactive pores are frequently found just beneath the casting surface (subsurface pinholes) and can be difficult to detect without destructive testing.

1.3 Solubility-Based (Precipitation) Porosity

This type of porosity in casting is governed by the changing solubility of gases in the metal between the liquid and solid states. Hydrogen is the primary culprit, especially in aluminum and steel. Hydrogen dissolves readily in the molten metal but its solubility plummets during solidification. If the initial hydrogen content is too high, the rejected gas cannot diffuse out in time and forms fine, often microscopic, pores distributed throughout the casting section. Sources include damp charge materials, rust, oily scrap, and a humid furnace atmosphere.

| Type of Porosity | Primary Gas Source | Typical Morphology & Location | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive Porosity | Mold/Core materials (resin, moisture) | Spherical/pear-shaped; near surfaces, upper sections | Sand gas generation rate, mold permeability, pouring temperature, metal head pressure |

| Reactive Porosity | Chemical reactions (metal-mold, within melt) | Subsurface pinholes, often associated with inclusions | Mold coating integrity, metal chemistry (oxygen content), deoxidation practice |

| Precipitation Porosity | Gas dissolved in molten metal (e.g., H₂) | Fine, dispersed pores throughout cross-section | Charge material condition, melting atmosphere, alloy composition |

2. The Alkaline Phenolic Resin Sand System: Characteristics and Risks

The shift towards alkaline phenolic resin (APR) no-bake systems has been driven by environmental and quality considerations. Its ester-curing mechanism produces a sand with favorable properties, yet a nuanced understanding is required to manage porosity in casting.

2.1 Advantages and Gas Generation Profile

APR sand offers low nitrogen and sulfur content, minimizing the risk of nitrogen porosity and metal surface deterioration. Its overall gas generation volume is typically lower than that of furan or acid-catalyzed phenolic resins. However, the gas evolution curve is critical. APR sands often exhibit a rapid initial gas release upon metal contact due to the decomposition of the ester catalyst and low-molecular-weight components of the resin. This initial surge coincides with the early stages of metal solidification, creating a window of high risk for invasive porosity in casting. The gas generation can be modeled as a time-dependent function:

$$ G(t) = G_0 e^{-k t} + G_1 (1 – e^{-λ t}) $$

Where $G(t)$ is the cumulative gas volume at time $t$, $G_0$ represents the instantly released volatile fraction, $k$ is its decay constant, $G_1$ is the gas from slower resin pyrolysis, and $λ$ is its rate constant.

2.2 Common Process-Related Vulnerabilities

Despite its advantages, several process weaknesses can exacerbate porosity in casting with APR sand:

- Sand Mixing and Reclamation: Inconsistent resin/catalyst ratios or inadequate mixing lead to uneven curing and potential localized high-gas zones. Overly high percentages of reclaimed sand without adequate thermal reactivation can lead to a buildup of carbonaceous material that increases gas generation.

- Inadequate Coating or Drying: Water-based or alcohol-based coatings applied to cores/molds must be thoroughly dried. Any residual solvent or carrier becomes a potent source of invasive gas.

- Poor Gating and Venting Design: Turbulent filling can chemically and mechanically erode the mold, increasing gas generation and carrying sand inclusions. Inadequate vents trap gases, increasing back-pressure.

3. A Systematic Case Study in Process Diagnosis and Rectification

The following analysis is based on a generalized but representative case involving a medium-carbon steel (similar to ZG35) component produced in APR sand, where significant porosity in casting was encountered. The initial process parameters are summarized below.

| Parameter Category | Initial Specification | Observed Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Part & Material | Rotational symmetry part; Medium Carbon Steel (~0.3%C) | Major porosity in casting clusters in upper regions between risers and above cores. Inclusions near ingates. |

| Molding Sand | APR no-bake; 70% reclaimed sand, 2% resin, 25% catalyst (on resin wt.) | |

| Gating System | Top/side gating with multiple ingates into risers. Sprue Ø70 mm. | |

| Pouring Practice | Pouring Temperature: ~1550°C |

3.1 Root Cause Analysis of the Observed Porosity

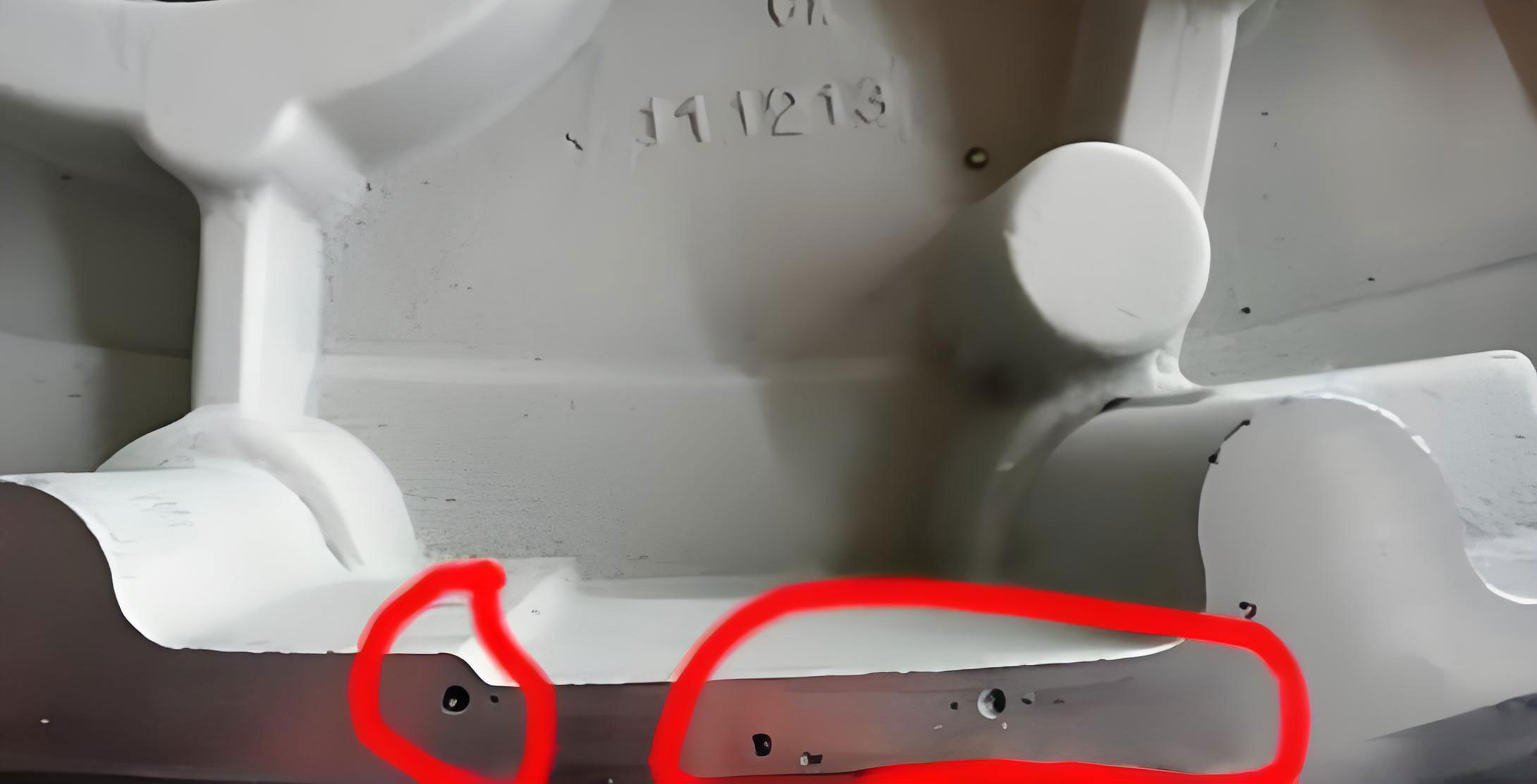

Sectioning and non-destructive testing of defective castings revealed the flaw distribution. The location of the porosity in casting provided critical clues:

- Upper Sections & “Hot Spot” Zones: Pores concentrated in the highest regions of the casting cavity, particularly in areas enclosed between large risers. This is a classic signature of invasive gas. The gases generated from the extensive mold surface area in these upper sections, combined with the lower metallostatic pressure ($P_{metal}$) there, created ideal conditions for gas entrapment. The risers, while feeding liquid, also presented large, unvented sand surfaces that contributed to the local gas load.

- Proximity to Cores: Pores found adjacent to the upper sections of sand cores indicated inadequate core venting. The gases generated within the core could not escape efficiently to the external atmosphere and were forced into the metal.

- Inclusions Near Ingates: The presence of slag inclusions near the ingates pointed to turbulent filling and potentially inadequate metal deoxidation. Turbulence accelerates mold erosion and air aspiration, while poor deoxidation can lead to both reactive CO formation and slag entrapment that can nucleate pores.

The primary failure mode was conclusively identified as invasive porosity in casting, driven by a combination of high localized gas generation and insufficient mold/core venting, exacerbated by a gating system that did not promote calm filling.

3.2 Integrated Corrective Action Plan

The mitigation strategy was holistic, targeting every stage from melting to mold design to address the root causes of porosity in casting.

3.2.1 Metallurgical and Melting Controls

- Charge Material Quality: Strict control over charge materials to ensure they are dry, clean, and free from rust, oil, and contaminants that introduce hydrogen and oxygen.

- Effective Deoxidation Practice: Implementing a balanced deoxidation sequence using aluminum and/or calcium silicide to fully reduce dissolved oxygen before pouring, minimizing the potential for reactive CO porosity in casting.

- Optimized Holding Time: Minimizing the liquid metal holding time after deoxidation to reduce hydrogen pickup from the atmosphere.

3.2.2 Radical Gating and Riser System Redesign

The most significant change was abandoning the top/side gating.

- Implementation of an Open Bottom-Pouring System: A downsprue leads to an extended runner along the bottom of the mold, with multiple, smaller ingates distributed upwards. This ensures:

- Calm, Non-Turbulent Filling: The metal rises steadily in the cavity, minimizing agitation, mold erosion, and air entrapment.

- Favorable Temperature Gradient: Creates a temperature gradient from bottom (coolest) to top (hottest), promoting directional solidification towards the risers.

- Continuous Gas Purge Path: As the metal front rises, it pushes mold gases ahead of it and upwards towards strategically placed vents, rather than trapping them.

- Use of Pre-formed Ceramic Components: The sprue, runner, and riser sleeves were replaced with dry, pre-fired ceramic components. This drastically reduces the volume of gas-generating sand in immediate contact with the initial, hottest metal stream.

- Riser Neck Modification and Venting: Riser necks were designed to minimize contact area with sand. Top risers were fitted with ceramic-top insulating sleeves to extend feeding while reducing sand surface area. Explicit vent holes were created in the mold cope in areas between risers.

3.2.3 Enhanced Mold and Core Technology

- Aggressive Mold Venting: Multiple, strategically placed vent wires (or punched vents) were added in the mold cope, especially in isolated high-point pockets between risers. In some cases, permeable foam boards were placed in these sand pockets to create guaranteed escape channels for gas.

- Core Design for Exhaust: All large cores were mandated to have hollow constructions with perforated metal armatures (chaplets). Core prints were designed to be open and large enough to provide an unimpeded exhaust path from the core interior to the outside of the mold.

- Stringent Coating and Drying Protocol: A strict process was enforced for applying and thoroughly flame-drying multiple coats of alcohol-based refractory coating until no residual fumes were detectable.

- Chill Management: Any external chills used were required to be shot-blasted clean, pre-heated, and coated with a thin protective wash to prevent outgassing from rust or moisture upon metal contact.

| Process Area | Initial Problem | Corrective Action | Mechanism of Porosity Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gating Design | Turbulent top/side gating | Calm, open bottom-pouring system | Reduces mold erosion, air aspiration, and provides a gas purge path. Lowers effective $P_{gas}$. |

| Feeding/Riser Tech | Large sand surface area in risers | Use of ceramic riser sleeves and pipes | Eliminates gas generation from riser walls, increases thermal efficiency. |

| Mold Venting | Inadequate or no vents in cope | Strategic venting in high-point pockets, use of permeable foam | Provides low-resistance escape routes for mold gases, preventing pressure build-up ($P_{gas}$). |

| Core Design | Solid cores, poor exhaust paths | Hollow cores with vented armatures, open core prints | Allows internal core gases to evacuate directly to mold exterior, not into the metal. |

| Metal Preparation | Potential inadequate deoxidation | Strict charge control, optimized deoxidation practice | Reduces dissolved gases (H₂, O₂) minimizing reactive and precipitation porosity in casting. |

4. Quantitative Considerations and Modeling Insights

While qualitative rules are essential, quantitative modeling provides a powerful tool for predicting and preventing porosity in casting. The key is to model the pressure field in the mold and the solidification sequence.

4.1 Modeling Gas Pressure and Metal Flow

The pressure of gas in the mold cavity ($P_{cavity}$) can be approximated by considering it as a porous medium flow problem. Darcy’s Law can be applied to model gas flow towards vents:

$$ v = -\frac{k}{μ} ∇P $$

Where $v$ is the gas filtration velocity, $k$ is the sand permeability, $μ$ is the gas viscosity, and $∇P$ is the pressure gradient. The goal of good venting design is to create a strong pressure gradient ($∇P$) directing gas towards the vents, keeping $P_{cavity}$ low at all points, especially ahead of the advancing metal front. A simplified condition to avoid invasive porosity in casting at a point with ferrostatic head $h$ is:

$$ P_{cavity}(x,y,z,t) < ρ g h(x,y,z,t) + \frac{2σ}{r_{crit}} $$

Here, $σ$ is the metal surface tension and $r_{crit}$ is the critical bubble nucleus radius. Process improvements like increased permeability (higher $k$) and more vents (steeper $∇P$) directly lower $P_{cavity}$.

4.2 Solidification Modeling for Porosity Prediction

Modern simulation software couples fluid flow, heat transfer, and gas pressure models. It can predict “last-to-freeze” regions where shrinkage and gas porosity are most likely to coincide. The famous Niyama criterion, while primarily for shrinkage, is often used as an indicator of regions susceptible to microporosity, which can be exacerbated by gas. The criterion is:

$$ G / \sqrt{\dot{T}} < C $$

Where $G$ is the thermal gradient, $\dot{T}$ is the cooling rate, and $C$ is an alloy-dependent constant. Low values of this ratio indicate areas of pasty, slow-to-feed solidification where gas bubbles, once formed, are easily trapped. Optimizing riser placement and chill use to increase $G$ in critical areas is a direct outcome of such analysis.

5. Conclusion and Foundry Philosophy

The successful elimination of porosity in casting in alkaline phenolic resin sand—or any molding process—is not achieved by a single “magic bullet.” It is the result of a systematic, integrated approach that acknowledges the multifactorial nature of the defect. As demonstrated in the case analysis, the primary culprit was invasive gas, and the solution lay in a synergistic combination of metallurgical control, a radically redesigned and calmer filling system, and a relentless focus on providing easy escape paths for all gases generated by the mold and cores.

The core philosophy is one of control and escape: control the sources of gas (dry materials, efficient deoxidation, ceramic components) and diligently facilitate the escape of inevitable gases (through optimized permeability, venting, and core design). Advanced simulation tools now allow us to model these phenomena with increasing accuracy, moving from trial-and-error to predictive correction. However, the fundamental principles remain grounded in a deep understanding of the physics and chemistry governing the interaction between molten metal and its mold. By adhering to these principles, the incidence of porosity in casting can be minimized, leading to significant improvements in product quality, reliability, and overall manufacturing economics.