In the field of high-pressure die casting, the persistent challenge of porosity in castings remains a primary focus for process engineers and metallurgists. The drive towards lightweight automotive components has intensified the use of aluminum and magnesium alloys, consequently raising the performance benchmarks for structural integrity. Porosity in casting is a critical defect that directly compromises mechanical properties, pressure tightness, and surface quality. The allowable porosity level in many critical components is now specified to be as low as 3-5%, necessitating a meticulous and systematic approach to its control. This article, drawn from extensive practical experience, details a comprehensive methodology for analyzing, categorizing, and ultimately eliminating the various forms of porosity in casting.

The battle against porosity in casting begins with precise identification. Not all internal voids are created equal; distinguishing between gas porosity, shrinkage porosity, and inclusions is the crucial first step. Gas pores, the primary subject here, typically exhibit smooth, rounded, or elliptical surfaces and can appear isolated or in clusters. In contrast, shrinkage defects are irregular, darker, and exhibit dendritic structures under magnification. Advanced inspection techniques are indispensable. X-ray radiography is the standard non-destructive method for initial detection, often guided by Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to pinpoint high-stress zones and by process simulation to identify potential air entrapment areas. For definitive classification, cross-sectioning and examination under optical or scanning electron microscopes are employed. Control standards, such as ASTM E505 Level 1 for critical areas, provide the quantitative framework for acceptability.

The formation mechanisms of porosity in casting are diverse. I categorize them into five primary types, each with a distinct root cause and corresponding solution strategy. A systematic approach involving identification, classification, root cause analysis, and corrective action is paramount for success.

1. Hydrogen Porosity

This form of porosity in casting originates from hydrogen dissolved in the molten alloy. Upon solidification, hydrogen’s solubility drops dramatically, causing it to precipitate and form fine, often pin-like, distributed pores. These can be extremely difficult to detect visually in thin-walled castings due to rapid solidification. The primary source of hydrogen is moisture (H₂O), which dissociates at molten metal temperatures, allowing atomic hydrogen to be absorbed.

Sources: Moisture in furnace atmosphere, humid charge materials (ingots, returns), contaminated tools, oil-containing machining chips, and damp refining fluxes.

Countermeasure: Rotary Degassing. The standard industry practice involves injecting an inert gas (Ar, N₂) into the melt via a rotating impeller. The impeller shears the gas into fine bubbles, providing a vast surface area. Dissolved hydrogen diffuses into these bubbles due to the partial pressure difference and is carried to the surface. The efficiency is governed by factors like rotor design, gas flow rate, rotation speed, and treatment time.

Process Control: The effectiveness of degassing is quantitatively assessed by measuring the density of a solidified sample. A reduced-pressure test (also known as a Straube-Pfeiffer test) is commonly used. The relative density \( \rho_r \) is calculated as:

$$ \rho_r = \frac{m_a}{m_a – m_w} $$

where \( m_a \) is the sample mass in air and \( m_w \) is its mass in water. A density close to the theoretical dense-metal density indicates successful hydrogen removal. The relationship between hydrogen content and pore formation can be described by Sievert’s Law for solubility: $$ C_{H} = K_{H} \sqrt{P_{H_2}} $$ where \( C_{H} \) is the dissolved hydrogen concentration, \( K_{H} \) is the equilibrium constant, and \( P_{H_2} \) is the partial pressure of hydrogen. Degassing aims to reduce \( P_{H_2} \) in the bubbles to nearly zero, driving \( C_{H} \) in the melt down.

2. Entrapped Air Porosity

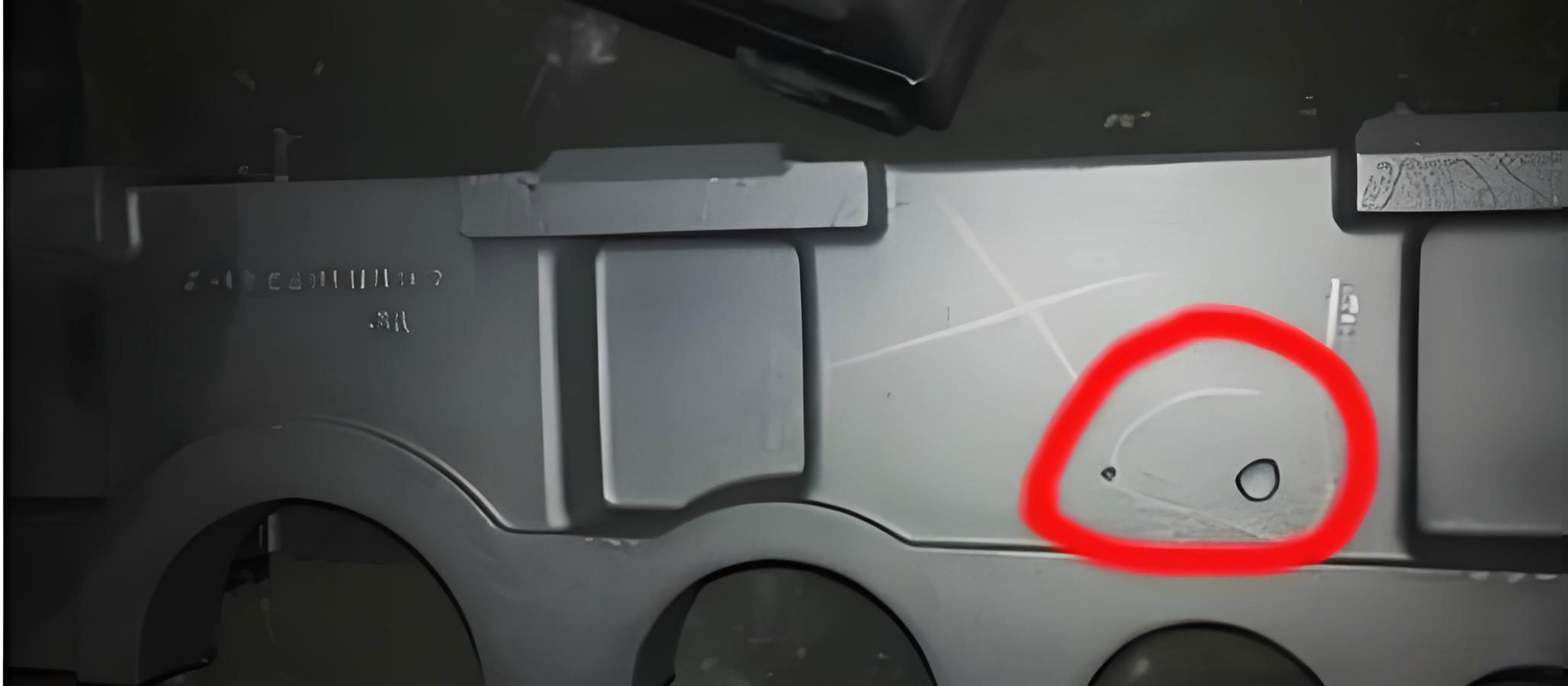

This is perhaps the most common form of porosity in casting in high-pressure die casting. It results from the turbulent entrapment of air during the filling process. The pores are usually spherical, clean, and shiny inside. Entrapment can occur at three main stages: the shot sleeve, the runner system, and the die cavity itself.

| Stage | Cause | Key Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Shot Sleeve (Cold Chamber) | Low fill percentage (<50%) causes metal wave turbulence and “air pumping” ahead of the plunger. | Optimize fill percentage to 70-80%. Use P-Q² analysis to select correct sleeve diameter. Synchronize plunger start with metal wave motion. Control slow shot speed profile. |

| Runner System | Sudden changes in direction or cross-section cause vortexing and air entrainment in the high-velocity flow. | Design runners with smooth transitions, avoiding sharp corners. Use tapered, hydraulically efficient profiles. |

| Die Cavity | Air is trapped at the liquid metal front if vents are inadequate or poorly located. | Design effective overflow and venting systems at last-to-fill areas (determined by simulation). Use shear vents or perimeter venting. Implement Vacuum Assisted HPDC. |

The role of process simulation (CAE) is indispensable for tackling entrapped air porosity in casting. Mold flow analysis can visually predict areas of air entrapment, allowing for optimization of gating and venting before tooling is built. The fill fraction \( f \) in the shot sleeve is a critical parameter:

$$ f = \frac{V_{metal}}{V_{sleeve}} $$

where a low \( f \) directly correlates to increased air volume available for entrainment. In vacuum die casting, the cavity pressure \( P_{cav} \) is drastically reduced from atmospheric levels (~100 kPa) to below 10 kPa, significantly minimizing the size and prevalence of this type of porosity in casting.

3. Steam (Water Vapor) Porosity

Porosity in casting caused by steam is characterized by rounded pores with a gray, dull, and often scaly or oxidized internal surface. The root cause is the presence of free water that contacts the molten metal, instantly vaporizing and expanding by a factor of approximately 1500. The resulting steam bubble is trapped in the solidifying metal.

Primary Sources:

- Excessive or poorly dried water-based die lubricant.

- Leaks in die cooling lines or connections.

- Cracks in the die allowing water ingress.

- Water dripping into the cavity from above the die.

- Residual hydraulic fluid on die surfaces.

Countermeasures: The strategy is entirely focused on prevention and control of moisture. This includes optimizing die spray parameters (volume, timing, air blow-off) based on thermal mapping of the die. Ensuring the die is completely dry before closing is critical. Regular maintenance checks for cooling line integrity, especially in high-thermal-stress areas like gate regions in hot-chamber machines, are mandatory to prevent catastrophic steam explosions, particularly with magnesium alloys.

4. Lubricant/Oil Porosity

This porosity in casting stems from the combustion and vaporization of organic lubricants. The pores often have a characteristic bronze, brown, or black tint on the surface. The two main sources are plunger lubricant in cold-chamber machines and excessive die lubricant.

For plunger lubricant, the issue arises when lubricant is applied to the tip of the plunger or in excessive amounts. It is drawn into the shot sleeve ahead of the metal wave, vaporizes, and is injected into the die. The solution is precise, automated lubrication applied to the side of the plunger, not the face, and using the minimum effective quantity. Worn plunger rings or shot sleeves exacerbate this problem by allowing metal “wash” and creating more surface area for lubricant accumulation and burn-off, directly increasing porosity in casting. A preventive maintenance schedule for plunger and sleeve replacement is essential.

5. Porosity from Inserts or Cores

Pre-placed inserts (e.g., steel liners in aluminum blocks) or complex sand cores can be a significant source of porosity in casting. The insert surface may contain oils, rust inhibitors, or moisture. When engulfed by molten metal, these contaminants volatilize, creating gas that cannot escape if the surrounding solidification is too rapid.

Solution Protocol:

- Cleaning: Inserts must be thoroughly cleaned to remove all surface contaminants.

- Preheating: Inserts must be preheated to a sufficient temperature (e.g., 250-400°C for steel in Al) and for a sufficient duration to drive off adsorbed gases and moisture. The preheating time \( t \) can be related to temperature \( T \) and insert mass to ensure thermal equilibrium.

- Process Control: The preheating process must be monitored and validated, often with poke-yoke systems to prevent the loading of cold inserts.

Systematic Approach and the Role of CAE

Eliminating porosity in casting is not a singular action but a systematic engineering process. It follows a defined cycle: Inspect -> Classify -> Analyze -> Solve -> Verify. Computer-Aided Engineering (CAE) is a cornerstone of this methodology, particularly for entrained air porosity.

Flow simulation software solves the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow to model the filling process:

$$ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \mathbf{u}) = 0 $$

$$ \frac{\partial (\rho \mathbf{u})}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \mathbf{u} \mathbf{u}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{\tau} + \rho \mathbf{g} $$

Where \( \rho \) is density, \( \mathbf{u} \) is velocity, \( p \) is pressure, and \( \boldsymbol{\tau} \) is the stress tensor. These simulations predict velocity fields, pressure gradients, and, most importantly, track the air volume fraction throughout the filling sequence. They allow for virtual optimization of gate design, overflow placement, and vacuum valve locations long before physical trials, saving substantial cost and time in resolving issues related to porosity in casting.

A holistic design philosophy using P-Q² diagrams ensures the machine, die, and process are matched. The P-Q² line represents the pressure-flow capability of the machine, while the die line represents the resistance of the die system. Their intersection defines the operating point. Optimizing this point ensures sufficient metal velocity is achieved without requiring excessive pressure that can exacerbate turbulence and porosity in casting.

Conclusion

The mitigation of porosity in casting is a multifaceted challenge that demands a deep understanding of metallurgy, fluid dynamics, and process engineering. Success hinges on the disciplined application of a diagnostic framework: accurate identification of the pore type based on its morphology, followed by targeted investigation into its specific root cause—be it hydrogen from the melt, air from turbulent filling, steam from moisture, gases from lubricants, or contaminants from inserts. Technological tools, from rotary degassing and vacuum systems to advanced CAE simulation, provide powerful means for both analysis and solution. Ultimately, controlling porosity in casting is about implementing a robust, monitored, and continuously improved process where each potential source of gas is systematically identified, controlled, and minimized to produce high-integrity castings that meet the ever-increasing demands of modern lightweight engineering.