In my years of experience working with pure copper castings, I have consistently encountered the pervasive challenge of porosity in casting. This defect not only compromises the structural integrity of components but also severely impacts their functional performance in critical applications such as high-conductivity electrical contacts, heat exchangers, and metallurgical tools. The quest to understand and eliminate porosity in casting has been a central focus of my research and practical endeavors. Porosity in casting, particularly in pure copper, arises from complex interactions between dissolved gases, melt chemistry, and solidification dynamics. Through this article, I aim to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms, reliable detection methods, and effective elimination strategies for porosity in casting, drawing upon both theoretical principles and hands-on foundry practices. I will employ formulas, tables, and detailed explanations to provide a thorough resource for engineers and metallurgists grappling with this issue.

The formation of porosity in casting is fundamentally tied to the solubility of gases in molten copper and their behavior during solidification. Pure copper, with its high conductivity, is exceptionally prone to gas absorption, leading to porosity in casting if not meticulously controlled. The primary gases involved are hydrogen and oxygen, with water vapor reaction playing a pivotal role. Let me begin by detailing the solubility of hydrogen in copper. Hydrogen dissolves atomically in molten copper, and its solubility is strongly temperature-dependent. The relationship can be expressed using Sieverts’ law: $$[H] = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}}$$ where [H] is the hydrogen concentration in the melt (often in weight percent or parts per million), \(K_H\) is the equilibrium constant that varies with temperature, and \(P_{H_2}\) is the partial pressure of hydrogen in the surrounding atmosphere. At 1200°C, under a hydrogen partial pressure of 1 atm, the solubility of hydrogen in liquid copper is approximately 6.0 cm³/100g Cu, while in solid copper at the same temperature, it drops to about 2.0 cm³/100g Cu. This drastic reduction upon solidification forces the excess hydrogen to precipitate, potentially forming porosity in casting. To illustrate, consider the following table summarizing hydrogen solubility at different temperatures and pressures:

| Temperature (°C) | \(P_{H_2}\) (atm) | Solubility in Liquid Cu (cm³/100g) | Solubility in Solid Cu (cm³/100g) | Potential for Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1083 (melting point) | 1.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 | High due to large drop |

| 1200 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | Very high |

| 1200 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.2 | Moderate, depends on oxygen content |

| 1000 | 1.0 | 4.5 | 1.5 | High |

From this data, it is evident that higher melting temperatures exacerbate hydrogen pickup, increasing the risk of porosity in casting. However, hydrogen alone is not always the sole culprit. Oxygen dissolution in copper is equally critical. Oxygen dissolves as Cu₂O, and its solubility is governed by the copper-oxygen phase diagram. In equilibrium, the maximum oxygen solubility in liquid copper at the eutectic temperature is about 0.39 wt%. Upon solidification, oxygen tends to segregate, leading to enriched zones in the last-to-freeze areas. This segregation can lower the effective hydrogen tolerance, as I will explain shortly. The interaction between hydrogen and oxygen via the water vapor reaction is the key mechanism driving porosity in casting. The reaction is: $$2[H] + [O] \rightleftharpoons H_2O_{(g)}$$ with the equilibrium constant given by: $$K = \frac{P_{H_2O}}{[H]^2 [O]}$$ where [H] and [O] are the activities (approximated by concentrations in dilute solutions) of hydrogen and oxygen in the melt, and \(P_{H_2O}\) is the water vapor partial pressure in the environment. This equation implies that for a given \(P_{H_2O}\), the product [H]²[O] is constant. Thus, if oxygen content is high, the allowable hydrogen content to avoid porosity in casting is low, and vice versa. For instance, at 1200°C with \(P_{H_2O} = 0.01\) atm, the equilibrium relationship can be plotted, showing that even modest oxygen levels drastically reduce the safe hydrogen limit. The following table derived from such calculations highlights this interdependence:

| \(P_{H_2O}\) (atm) | [O] = 10 ppm | [O] = 50 ppm | [O] = 100 ppm | [O] = 200 ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | [H] ≈ 31.6 ppm | [H] ≈ 14.1 ppm | [H] ≈ 10.0 ppm | [H] ≈ 7.1 ppm |

| 0.01 | [H] ≈ 10.0 ppm | [H] ≈ 4.47 ppm | [H] ≈ 3.16 ppm | [H] ≈ 2.24 ppm |

| 0.1 | [H] ≈ 3.16 ppm | [H] ≈ 1.41 ppm | [H] ≈ 1.0 ppm | [H] ≈ 0.71 ppm |

This table underscores that in typical foundry environments where water vapor pressure can be significant (e.g., from fuel combustion or humid air), the combined effect of hydrogen and oxygen must be carefully managed to prevent porosity in casting. Moreover, during solidification, microsegregation can locally elevate oxygen concentrations in interdendritic regions, making those areas more susceptible to water vapor formation even if bulk averages seem safe. Thus, controlling both gases is paramount. Another factor is melting temperature; higher temperatures increase K, raising the [H]²[O] product for a given \(P_{H_2O}\), thereby enhancing the tendency for porosity in casting. I often recommend keeping melting temperatures as low as feasible, just above the liquidus, to minimize gas absorption.

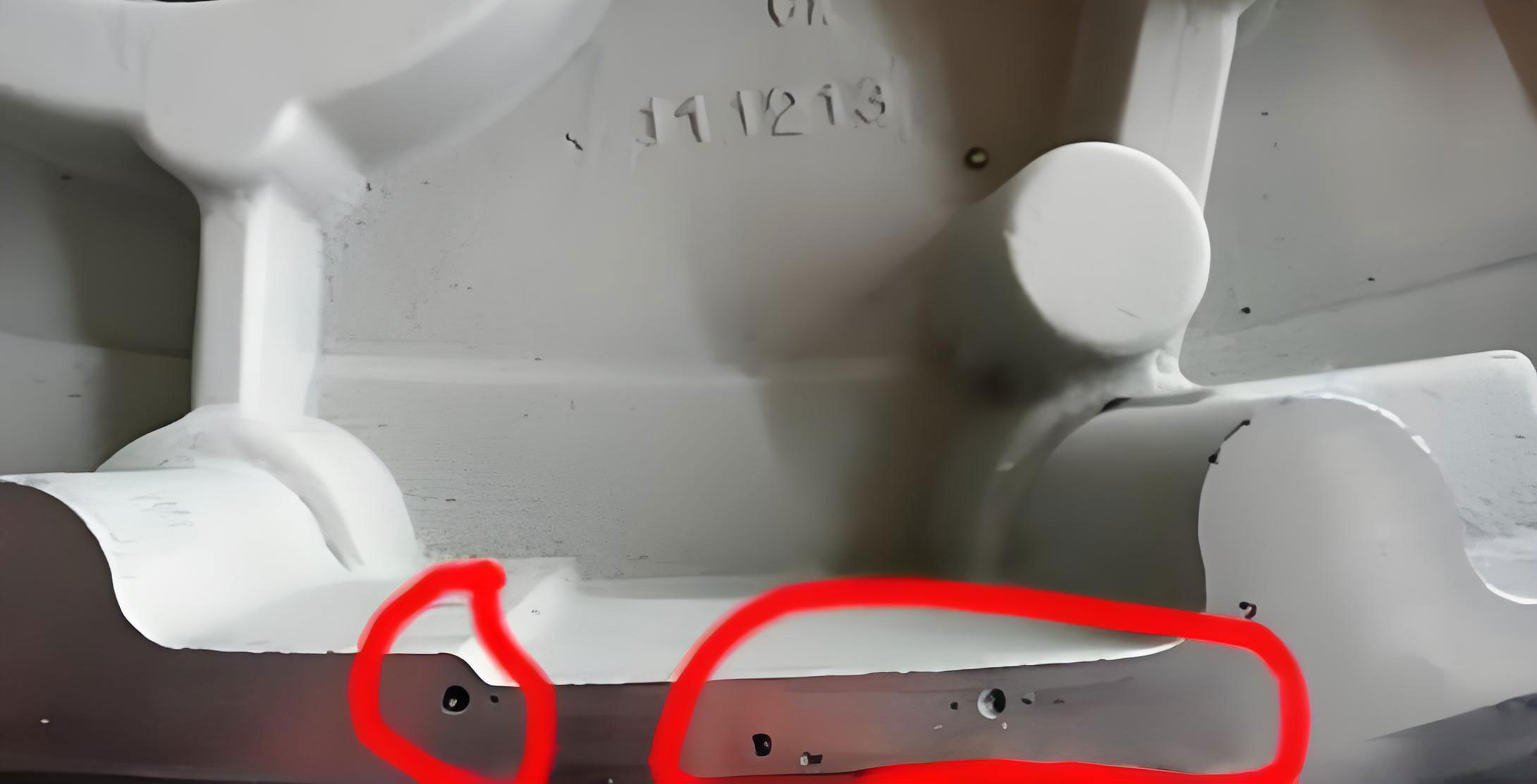

The visual manifestation of porosity in casting can vary from macroshrinkage to microvoids, as illustrated in the image above, which underscores the importance of detection. Moving to detection methods, I have found the reduced pressure test (also known as the vacuum solidification test) to be exceptionally valuable for quantifying gas content in copper melts. This method involves placing a small sample of molten copper in a crucible inside a vacuum chamber, gradually reducing the pressure, and observing the surface morphology of the solidifying metal. As the pressure drops, the dissolved gases come out of solution, forming bubbles that can be correlated to the total gas content. The apparatus typically consists of a vacuum chamber, a viewing port, a pressure gauge, and a crucible embedded in a granular refractory bed. The process reveals three distinct surface profiles: a calm surface (indicating equilibrium), a domed surface (indicating gas evolution), and a ruptured surface (indicating excessive gas). The pressure at which bubbling initiates is recorded, and it correlates with the total gas content. I have compiled data from numerous tests to establish a relationship, which can be summarized as:

| Equilibrium Pressure (mbar) | Interpretation | Total Gas Content (approx. cm³/100g) | Likelihood of Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 500 | Low gas content | < 1.0 | Low |

| 200 – 500 | Moderate gas content | 1.0 – 3.0 | Moderate, requires caution |

| 50 – 200 | High gas content | 3.0 – 6.0 | High, likely to cause defects |

| < 50 | Very high gas content | > 6.0 | Very high, castings will be porous |

This test is not only rapid but also economical, making it ideal for foundry floor use. By regularly monitoring melts with this technique, I have been able to adjust processing parameters proactively to mitigate porosity in casting. It is crucial to note that the test reflects the combined effect of all dissolved gases, primarily hydrogen and oxygen through their reaction products. Therefore, it serves as an excellent indicator of the overall propensity for porosity in casting.

Having established the causes and detection methods, let me delve into the strategies I employ to eliminate porosity in casting. These measures can be categorized into mechanical (or physical) methods and chemical methods. Mechanical methods aim to remove dissolved gases through physical means, while chemical methods involve adding elements to bind gases or alter melt chemistry. Starting with mechanical methods, one effective approach is inert gas purging. By bubbling dry nitrogen or argon through the melt via a refractory-coated lance, I can entrain dissolved hydrogen and carry it to the surface. The efficiency depends on bubble size and flow rate; finer bubbles and longer treatment times enhance removal. For a 500 kg furnace, I typically use a flow rate of 10-20 L/min for 10-15 minutes. Another mechanical method is vacuum degassing, where the entire melt is subjected to reduced pressure, allowing gases to expand and escape. Although equipment-intensive, it is highly effective for high-quality castings. A simpler alternative is the use of gas-evolving compounds, such as adding dried limestone (CaCO₃) or fluoropolymers like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) to the melt bottom. Upon decomposition, they release CO₂ or other gases, causing agitation and degassing. However, care must be taken to avoid excessive turbulence that might reintroduce gases. The following table compares these mechanical methods:

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Parameters | Advantages | Limitations | Effectiveness Against Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inert Gas Purging | Physical entrainment and flotation of gas bubbles | N₂ or Ar, 5-30 L/min per ton, 10-20 min | Simple, low cost, good for hydrogen removal | May not remove oxygen; requires gas supply | High for hydrogen-related porosity |

| Vacuum Degassing | Reduced pressure lowers gas solubility | Pressure < 1 mbar, 5-15 min | Very effective for all gases, clean process | Expensive equipment, batch processing | Very high for overall porosity |

| Gas-Evolving Compounds | Decomposition releases gases causing melt agitation | CaCO₃ at 0.1-0.5 wt%, added to melt bottom | Low cost, easy implementation | Can introduce impurities; control of reaction is tricky | Moderate to high, depends on compound |

| Electromagnetic Stirring (in induction furnaces) | Natural convection and surface exposure | Inherent in induction melting | No additives, continuous action | Limited to induction furnaces; may not suffice alone | Moderate, often used in combination |

Chemical methods are essential for addressing oxygen, which indirectly influences porosity in casting through the water vapor reaction. The most common chemical deoxidizer is phosphorus-copper (Cu-P) master alloy, typically added as Cu-15%P. Phosphorus reacts with oxygen to form P₂O₅, which floats out as a slag. The reaction is: $$5[O] + 2[P] \rightarrow P_2O_5_{(g)}$$ However, excessive phosphorus can lead to residual phosphorus in the melt, which lowers electrical conductivity and may increase hydrogen solubility by reducing oxygen activity. Therefore, I advocate for controlled additions, often followed by a final deoxidation with a mild agent. Alternative deoxidizers include boron (added as Al-B or Cu-B alloys), calcium boride (CaB₆), and rare earth metals (e.g., mischmetal). These can be more effective in some cases, especially when phosphorus residuals are undesirable. For instance, boron offers strong deoxidation without significantly affecting conductivity. Rare earths can also modify inclusions and improve melt cleanliness. Below is a table summarizing chemical deoxidation options:

| Deoxidizer | Typical Addition Form | Addition Rate (wt% of melt) | Mechanism | Key Considerations | Impact on Porosity in Casting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus-Copper (Cu-P) | Cu-15%P master alloy | 0.02-0.1% P | Forms P₂O₅ gas, removes oxygen | Excess P reduces conductivity; does not remove H₂ | High for oxygen-related porosity, but must control H₂ separately |

| Boron | Al-5%B or Cu-2%B | 0.005-0.02% B | Forms B₂O₃ slag, strong deoxidizer | Minimal effect on conductivity; can be expensive | Very high for oxygen removal, indirectly reduces porosity risk |

| Calcium Boride (CaB₆) | Powder or tablet | 0.01-0.05% | Releases Ca and B for deoxidation | Exothermic reaction; requires careful handling | High, effective in combined deoxidation |

| Rare Earth Metals (e.g., Mischmetal) | Ingot or wire | 0.05-0.2% | Forms stable oxides and sulfides, also may degas | Costly; can improve mechanical properties | Moderate to high, depends on melt condition |

| Carbon (as graphite) | Graphite rods or powder | 0.05-0.2% C | Forms CO/CO₂ gas, deoxidizes | Risk of carbon pickup; suitable for certain alloys only | Moderate, but less common for pure Cu |

In practice, I often combine mechanical and chemical methods for optimal results. For example, in an induction furnace melt, I might first use electromagnetic stirring to naturally degas, then add a Cu-P deoxidizer to lower oxygen, followed by a short nitrogen purge to remove residual hydrogen. This multi-step approach has consistently yielded castings free from porosity in casting. Additionally, process parameters such as melt temperature, holding time, and furnace atmosphere play crucial roles. I always emphasize the importance of using dry, preheated charge materials to minimize hydrogen pickup from moisture. Cover fluxes like charcoal or graphite blocks can protect the melt from oxidation, but they must be thoroughly dried to avoid introducing water vapor. In fuel-fired furnaces, where atmosphere control is harder, I recommend employing more aggressive degassing and deoxidation routines.

To quantify the effectiveness of these measures, I have developed empirical models based on the equilibrium constants. For instance, after deoxidation, the residual oxygen content can be estimated using the deoxidizer’s equilibrium constant. Suppose we use phosphorus deoxidation at 1200°C. The equilibrium constant for the reaction \(2[P] + 5[O] \rightleftharpoons P_2O_5\) is approximately \(K_P \approx 10^{-10}\) at that temperature. If we target a final phosphorus content of 0.01 wt%, the equilibrium oxygen level can be calculated as: $$[O] = \left( \frac{K_P}{[P]^2} \right)^{1/5}$$ Plugging in values: $$[O] = \left( \frac{10^{-10}}{(0.01)^2} \right)^{1/5} = \left( \frac{10^{-10}}{10^{-4}} \right)^{1/5} = (10^{-6})^{1/5} = 10^{-1.2} \approx 0.063 \text{ wt%}$$ This is relatively high, indicating that phosphorus alone may not reduce oxygen enough for very high-purity applications. Hence, a second deoxidizer like boron might be needed. Such calculations guide my selection of deoxidation sequences to minimize porosity in casting.

Another aspect is solidification design. By optimizing gating and risering systems to promote directional solidification, I can reduce the trapping of gases in isolated pockets. Chill plates or controlled cooling rates can also help in managing gas precipitation. However, these are supplemental to melt treatment. Throughout my work, I have maintained that prevention is better than cure; hence, rigorous monitoring via the reduced pressure test is indispensable. I often set threshold pressures for specific casting applications—for example, for critical conductivity components, I require a test pressure above 400 mbar before pouring.

In conclusion, porosity in casting is a multifaceted defect in pure copper that stems from the interplay of hydrogen, oxygen, and water vapor. Through a deep understanding of solubility laws and reaction equilibria, coupled with robust detection and elimination techniques, it is possible to produce sound, high-integrity castings. My approach integrates mechanical degassing methods like inert gas purging with chemical deoxidation using tailored agents, all while controlling process variables such as temperature and atmosphere. The key is to recognize that porosity in casting is not inevitable; with diligent practice and scientific insight, it can be effectively mitigated. I hope this detailed exposition provides a valuable framework for foundries and researchers aiming to conquer the challenge of porosity in casting in pure copper and similar high-conductivity alloys.