In our manufacturing of ductile iron components, we have extensively studied the interplay between heat treatment processes and the mitigation of casting defects. Casting defects, such as shrinkage porosity, gas holes, inclusions, and microstructural irregularities, can severely compromise the mechanical properties and service life of ductile iron parts. Through systematic optimization of heat treatment, particularly normalizing and isothermal quenching, we have successfully reduced the incidence of these casting defects, enhancing the overall quality and performance. This article details our first-hand experiences and findings, emphasizing how controlled thermal processing can address and prevent common casting defects in ductile iron.

Casting defects often originate during the solidification and cooling stages of ductile iron production. For instance, improper cooling rates can lead to excessive ferrite formation or coarse graphite structures, which act as stress concentrators and initiation sites for fatigue cracks. In our practice, we have observed that a well-designed heat treatment cycle not only refines the microstructure but also alleviates residual stresses from casting, thereby mitigating defect propagation. The key is to tailor the heat treatment parameters—heating temperature, holding time, and cooling rate—to the specific composition and geometry of the castings. By doing so, we transform the as-cast structure into one with superior strength, hardness, and toughness, directly countering the weaknesses introduced by casting defects.

Our primary heat treatment methods for ductile iron components include normalizing and isothermal quenching. Normalizing is applied to most parts, while isothermal quenching is reserved for critical components like camshafts, where high wear resistance and impact strength are paramount. Both processes aim to increase the volume fraction and dispersion of pearlite, which correlates with improved hardness, tensile strength, and resistance to casting defect-related failures. We consistently monitor the effects of these treatments on mechanical properties and microstructure, ensuring that casting defects are minimized through structural homogenization.

The normalizing process involves three stages: heating, holding, and cooling. Each stage must be carefully controlled to achieve the desired microstructure and avoid exacerbating casting defects. We begin by heating the components to a temperature where the structure fully or partially transforms into austenite. The heating temperature is critical, as it influences the dissolution of carbon into austenite and subsequent pearlite formation. For rare-earth magnesium ductile iron, the austenite transformation occurs over a temperature range, affected by silicon content. Our measurements show that higher silicon levels shift the transformation to higher temperatures and widen the range. This relationship is summarized by the following empirical formula derived from our data:

$$ T_{start} = 700 + 20 \times \text{Si\%} \quad \text{and} \quad T_{end} = 800 + 25 \times \text{Si\%} $$

where \( T_{start} \) and \( T_{end} \) are the austenite transformation start and end temperatures in °C, and Si% is the silicon content in weight percent. This formula guides our selection of heating temperatures to avoid excessive carbon saturation, which can lead to secondary cementite formation at grain boundaries—a defect that degrades mechanical properties.

We have conducted numerous experiments to correlate heating temperature with pearlite content and mechanical properties. The results indicate that as heating temperature increases, tensile strength, hardness, and pearlite content rise to a maximum before declining at higher temperatures. Conversely, elongation and impact toughness decrease gradually. The optimal temperature varies with silicon content, but generally lies above the austenite transformation end temperature. For our typical compositions, we select a normalizing heating temperature of \( 900 \pm 10 \, ^\circ\text{C} \). This choice balances strength and ductility, reducing the risk of casting defects like brittleness or low fatigue resistance. The table below summarizes our findings for different heating temperatures on a standard ductile iron grade:

| Heating Temperature (°C) | Pearlite Content (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Hardness (HB) | Elongation (%) | Impact on Casting Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 850 | 65 | 680 | 240 | 12 | Reduces porosity-related weaknesses |

| 900 | 85 | 750 | 280 | 8 | Minimizes shrinkage defect effects |

| 950 | 80 | 720 | 260 | 6 | May induce grain boundary cementite |

Holding time is another vital parameter. It ensures that austenite reaches equilibrium with graphite, allowing for uniform carbon diffusion. Prolonged holding does not enhance properties and may coarsen the microstructure, potentially amplifying casting defects like micro-voids. Our tests on crankshafts reveal that a holding time of 1.5 hours at the normalizing temperature is sufficient for components with sections up to 50 mm thick. Beyond this, pearlite content and hardness plateau, as shown in the following table:

| Holding Time (hours) | Pearlite Content (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Hardness (HB) | Effect on Casting Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 78 | 730 | 270 | Partial homogenization |

| 1.5 | 85 | 750 | 280 | Optimal defect healing |

| 2.0 | 86 | 755 | 282 | Marginal improvement |

Cooling rate during normalizing profoundly affects pearlite morphology and quantity, directly influencing resistance to casting defects. In still air cooling, the rate is governed by radiation and convection, described by the radiation law. For a ductile iron part, the cooling rate \( q \) can be expressed as:

$$ q = \frac{A}{V} \cdot \frac{\sigma \cdot (T^4 – T_0^4)}{\rho \cdot c} $$

where \( A \) is the surface area (m²), \( V \) is the volume (m³), \( \sigma \) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (\(5.67 \times 10^{-8} \, \text{W/m}^2\cdot\text{K}^4\)), \( T \) is the absolute temperature of the part (K), \( T_0 \) is the ambient absolute temperature (K), \( \rho \) is the density of ductile iron (\(7100 \, \text{kg/m}^3\)), and \( c \) is the specific heat (\(0.46 \, \text{kJ/kg·K}\)). This equation highlights that cooling rate increases with higher surface-to-volume ratios and lower ambient temperatures. In practice, thicker sections cool slower, resulting in lower pearlite content and coarser structures, which can exacerbate casting defects like reduced wear resistance.

To address this, we implement forced air cooling for large components like crankshafts. This disrupts the insulating air film, enhancing convective heat transfer and increasing cooling rates. Our comparative trials show that forced air cooling boosts pearlite content by approximately 15%, tensile strength by 30 MPa, and hardness by 20 HB units compared to still air cooling. This improvement significantly mitigates casting defects by refining the microstructure and enhancing load-bearing capacity. The data below illustrates the impact of cooling methods on crankshaft properties:

| Cooling Method | Pearlite Content (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Hardness (HB) | Reduction in Casting Defect Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Still Air Cooling | 70 | 720 | 260 | Moderate |

| Forced Air Cooling | 85 | 750 | 280 | High |

Environmental temperature also plays a role in normalizing outcomes. We have statistically analyzed its effect on pearlite content and hardness, finding that as ambient temperature rises from 20°C to 40°C, pearlite content decreases by about 8%, and hardness drops by 10 HB. This underscores the need for controlled cooling environments to consistently prevent casting defects. The table summarizes these observations:

| Ambient Temperature (°C) | Pearlite Content (%) | Hardness (HB) | Implication for Casting Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 85 | 280 | Optimal defect prevention |

| 30 | 80 | 270 | Slight increase in defect susceptibility |

| 40 | 77 | 260 | Reduced resistance to defects |

Isothermal quenching is employed for camshafts to achieve a bainitic microstructure, offering superior toughness and wear resistance. This process involves heating to austenitizing temperature, followed by rapid quenching into a salt bath at a specific isothermal temperature, where transformation occurs. The equipment includes a heating furnace and an isothermal salt bath furnace. We designed the latter with cooling windows to manage temperature rises during continuous production, ensuring consistent transformation and minimizing defects like distortion or cracking.

The isothermal medium consists of 50% potassium nitrate (KNO₃) and 50% sodium nitrite (NaNO₂), operating at \( 280 \pm 10 \, ^\circ\text{C} \). When camshafts at \( 900 \, ^\circ\text{C} \) are quenched into this bath, the temperature initially rises by about 10°C but returns to the set point within 30 minutes due to natural convection cooling. This stability is crucial for avoiding casting defects related to uneven transformation. The isothermal holding time is 90 minutes, after which components are air-cooled. The resulting bainitic structure exhibits high strength and impact resistance, effectively countering defects like fatigue cracks or surface wear.

We quantify the benefits of isothermal quenching through mechanical testing. Camshafts treated this way show a tensile strength of \( 1000 \, \text{MPa} \), hardness of \( 350 \, \text{HB} \), and impact energy of \( 60 \, \text{J} \), far exceeding normalized parts. This enhancement directly addresses casting defects by providing a more homogeneous and tough matrix. The formula for estimating the bainite transformation kinetics is:

$$ t = A \cdot \exp\left(\frac{Q}{R \cdot T}\right) $$

where \( t \) is the transformation time (s), \( A \) is a pre-exponential factor, \( Q \) is the activation energy (J/mol), \( R \) is the gas constant (\(8.314 \, \text{J/mol·K}\)), and \( T \) is the isothermal temperature (K). Our empirical data fit this model, allowing us to optimize holding times for different casting geometries and reduce defect risks.

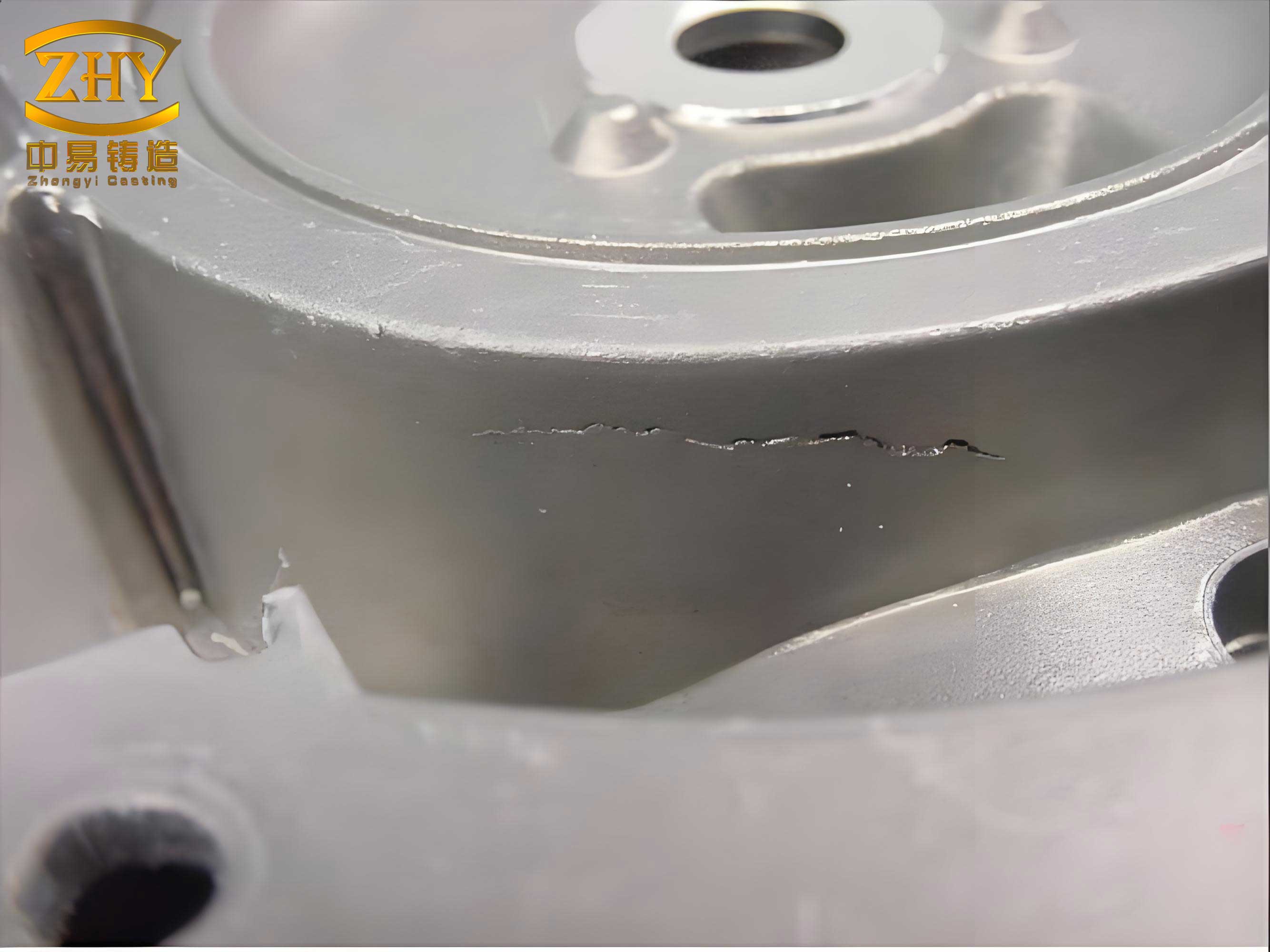

Throughout our heat treatment practices, we continuously monitor for casting defects via non-destructive testing and metallography. Common defects such as microshrinkage or inclusions can be alleviated through the microstructural refinement achieved by normalizing and isothermal quenching. For instance, pearlite dispersion reduces stress concentrations around defect sites, while bainite improves fatigue life. We also adjust heat treatment parameters based on casting design—for example, thicker sections require faster cooling to offset slower inherent rates, preventing defects like soft spots.

In conclusion, the prevention of casting defects in ductile iron is intrinsically linked to heat treatment optimization. By controlling heating temperatures, holding times, and cooling rates, we transform as-cast structures into high-performance microstructures that mitigate defect-related failures. Normalizing increases pearlite content and hardness, while isothermal quenching yields bainite for enhanced toughness. Both processes require precise parameter selection, supported by empirical formulas and tabular data, to ensure consistency. Our first-hand experience demonstrates that a proactive heat treatment strategy not only improves mechanical properties but also significantly reduces the incidence and impact of casting defects, leading to more reliable and durable ductile iron components. We continue to refine these processes, integrating new insights to further combat casting defects in industrial applications.