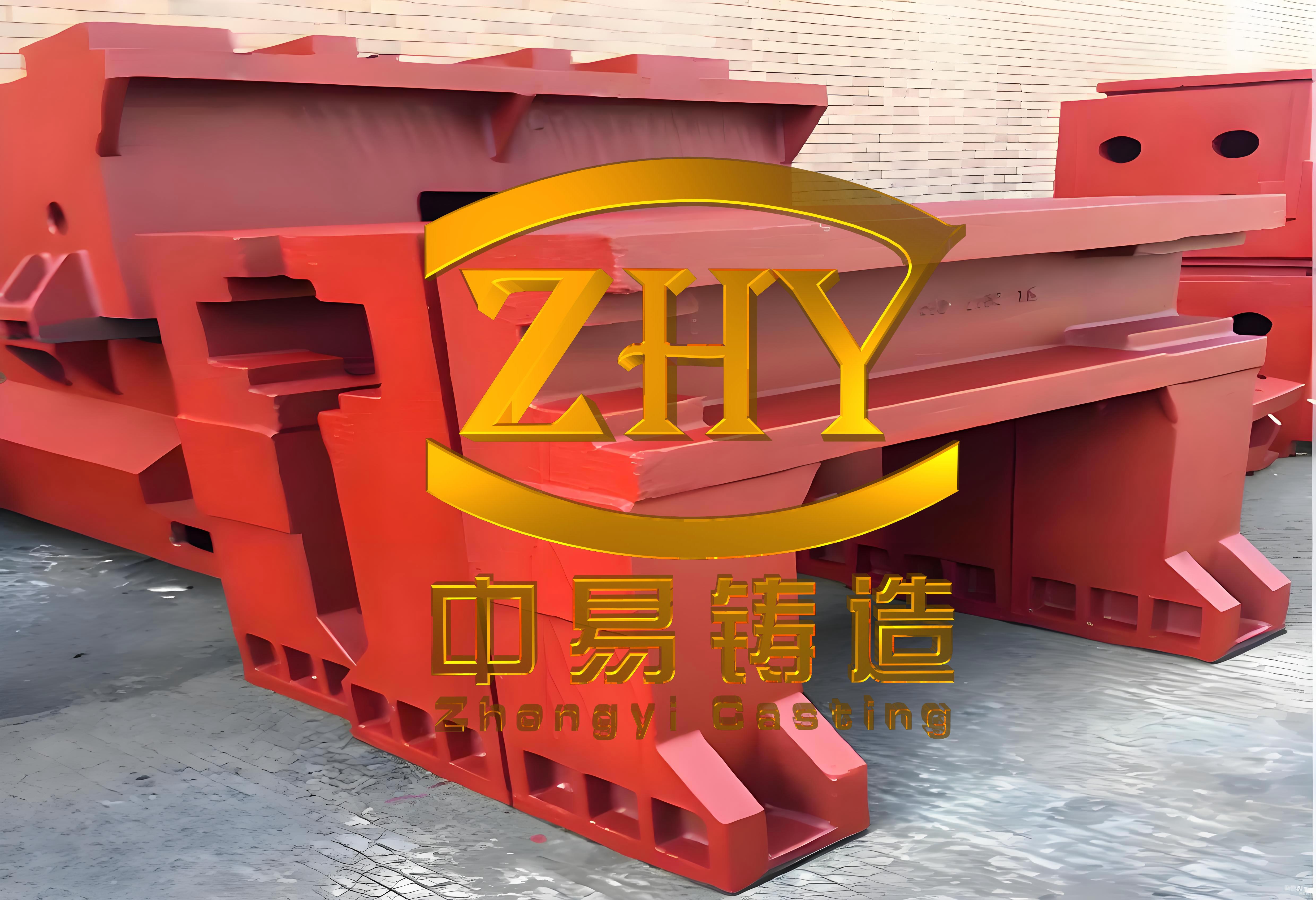

In the manufacturing of machine tool castings, particularly for complex components like slip pillows, we have encountered significant challenges that impact product quality and cost-efficiency. Machine tool castings are critical for industrial applications, requiring high dimensional accuracy, structural integrity, and minimal defects. As part of our ongoing efforts to enhance the production process for machine tool castings, we focused on addressing common issues such as inclusions, gas holes, and shrinkage porosity. These defects often lead to high rejection rates, increasing costs and delaying production schedules. Through a series of systematic improvements, including changes in production methods and process schemes, we aimed to reduce defect rates, improve yield, and achieve substantial cost savings. This article details our first-person experience in implementing these changes, supported by data analysis, tables, and mathematical models to illustrate the outcomes. The insights gained can benefit others working with similar machine tool castings, emphasizing the importance of tailored process adjustments for complex geometries.

Machine tool castings, especially slip pillow components, are notoriously difficult to produce due to their intricate internal structures, high precision requirements, and the need for extensive machining on all surfaces. In our production line, we observed that defects like inclusions and gas holes were prevalent, leading to scrap rates as high as 100% in some cases. For instance, in the production of machine tool castings such as those for龙门数控镗铣床 and龙门加工中心, we faced issues where gas emissions from resin sand molding and inadequate venting caused catastrophic failures. To tackle this, we initiated a comprehensive analysis, starting with data collection and root cause identification. We found that the traditional horizontal pouring method exacerbated inclusion defects, as impurities in the molten iron could not be effectively floated out. Additionally, the limited venting area in the mold cavity contributed to gas entrapment. By adopting a specialized production team approach and modifying the pouring orientation, we sought to optimize the process for these demanding machine tool castings.

The economic impact of these defects was substantial, with annual losses exceeding significant figures. For example, reducing the rejection rate by 5% in a production volume of 40,000 pieces annually saved approximately 290,000 units of currency. Furthermore, improving the process yield by 10% led to raw material savings of 567,000 units per year, while changes in core sand usage cut costs by 238,000 units. In total, these adjustments resulted in annual savings of around 1.09 million units. This underscores the importance of continuous improvement in machine tool castings production, where even minor enhancements can yield considerable financial benefits. In the following sections, we will delve into the specific methods employed, including statistical analysis, cause-effect relationships, and the implementation of innovative pouring techniques.

Data Analysis and Defect Identification

To understand the scope of the problem, we compiled data from our production records for various machine tool castings, focusing on slip pillow components. The table below summarizes the production and rejection rates for different products over a specified period. This data highlights the severity of defects and the need for targeted interventions.

| Product Name | Production Quantity (units) | Rejection Quantity (units) | Rejection Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Tool Casting A (42200 Square Slip Pillow) | 13 | 6 | 46.15 |

| Machine Tool Casting B (42160C Slip Pillow) | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| Machine Tool Casting C (2740 Slip Pillow) | 4 | 3 | 75.00 |

| Machine Tool Casting D (42125 Slip Pillow) | 4 | 2 | 50.00 |

From this data, it is evident that rejection rates were unacceptably high, necessitating a deeper analysis of defect types. The following table breaks down the predominant defects observed in the rejected machine tool castings, providing insight into their frequency and impact.

| Defect Type | Quantity (units) | Percentage of Total Rejects (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusions | 4 | 26.67 |

| Gas Holes | 5 | 33.33 |

| Shrinkage Porosity | 3 | 20.00 |

| Sand Erosion | 3 | 20.00 |

Based on this analysis, we identified that inclusions and gas holes were the most critical issues, accounting for over 60% of the defects in machine tool castings. To model the defect formation, we used mathematical representations. For instance, the rate of inclusion defects can be expressed as a function of sand cleanliness and flow dynamics: $$ I = k \cdot \int_{0}^{t} C_s \, dt $$ where \( I \) is the inclusion index, \( k \) is a proportionality constant related to sand properties, \( C_s \) is the concentration of loose sand in the mold cavity, and \( t \) is time. Similarly, gas hole formation can be described by the ideal gas law applied to mold venting: $$ P_g V = nRT $$ where \( P_g \) is the gas pressure, \( V \) is the volume of the cavity, \( n \) is the number of moles of gas, \( R \) is the gas constant, and \( T \) is the temperature. Inadequate venting leads to high \( P_g \), causing gas entrapment in the machine tool castings.

Further root cause analysis revealed that inclusions primarily stemmed from residual sand in the mold cavity, insufficient core strength leading to erosion during pouring, and instability during mold flipping in horizontal pouring setups. For gas holes, the limited venting area in vertical pouring configurations was a key factor, compounded by high resin and hardener usage in the sand mix, which increased gas generation. Shrinkage porosity was attributed to inadequate riser design and poor venting in risers, causing backpressure issues. These insights guided our improvement strategies, focusing on process optimization for machine tool castings.

Improvement Methods and Implementation

To address the defects in machine tool castings, we implemented a multi-faceted approach, starting with organizational changes and progressing to technical modifications. First, we established a specialized production team dedicated solely to slip pillow components. This team handled core making, molding, and box closing as an integrated process, enhancing coordination and skill development. By focusing exclusively on these complex machine tool castings, we improved process consistency and reduced inter-stage errors. This organizational shift alone contributed to a 30% increase in production efficiency, as team members became adept at identifying and resolving issues in real-time.

Next, we introduced two primary technical schemes: “horizontal molding and vertical pouring” (Scheme 1) and “inclined pouring” (Scheme 2). Scheme 1 involved creating the mold in a horizontal position and then rotating it to a vertical orientation for pouring. This allowed impurities in the molten iron to float upward and concentrate in a specific area of the slip pillow, which could later be machined away. The effectiveness of this method for reducing inclusions in machine tool castings can be modeled using a buoyancy-driven separation equation: $$ v_b = \frac{2}{9} \frac{(\rho_p – \rho_f) g r^2}{\mu} $$ where \( v_b \) is the terminal velocity of impurities, \( \rho_p \) and \( \rho_f \) are the densities of the impurity and fluid, respectively, \( g \) is gravity, \( r \) is the radius of the impurity particle, and \( \mu \) is the dynamic viscosity. By optimizing pouring parameters, we maximized \( v_b \) to enhance impurity removal.

However, Scheme 1 still faced challenges with gas venting, as the vertical orientation limited the effective venting area. To overcome this, we developed Scheme 2, inclined pouring, where the mold was tilted at an angle during pouring. This increased the venting surface area and allowed for multiple venting risers, effectively reducing gas hole defects. The venting efficiency can be quantified by the ratio of venting area to cavity volume: $$ \eta_v = \frac{A_v}{V_c} $$ where \( \eta_v \) is the venting efficiency, \( A_v \) is the total venting area, and \( V_c \) is the cavity volume. By increasing \( \eta_v \) through inclined pouring, we minimized gas entrapment in machine tool castings. Additionally, we revised core design by thickening rib plates from 12 mm to 15 mm, improving strength and reducing deformation during pouring. We also standardized sand parameters to control resin and hardener ratios, ensuring consistent mold strength.

The implementation of these methods was supported by detailed operating procedures and training. For example, we created a dedicated作业指导书 for slip pillow production, emphasizing steps like core iron usage and mold stability checks. The table below summarizes the key process parameters adjusted for machine tool castings under each scheme, highlighting the optimizations made.

| Parameter | Scheme 1 (Horizontal Molding, Vertical Pouring) | Scheme 2 (Inclined Pouring) |

|---|---|---|

| Pouring Orientation | Vertical | Inclined (15-30 degrees) |

| Venting Risers | Limited number | Multiple, strategically placed |

| Core Strength | Standardized sand mix | Enhanced rib thickness (15 mm) |

| Production Team | Specialized group | Same specialized group |

| Defect Focus | Inclusions | Gas holes and inclusions |

Through these improvements, we aimed to achieve a holistic enhancement in the quality of machine tool castings, reducing defects and increasing yield. The mathematical modeling of these processes helped us predict outcomes and fine-tune parameters, such as pouring temperature and time, to optimize results. For instance, the total cost savings from defect reduction can be expressed as: $$ S = (R_b – R_a) \cdot Q \cdot C_u + \Delta Y \cdot M_s $$ where \( S \) is the total savings, \( R_b \) and \( R_a \) are the rejection rates before and after improvement, \( Q \) is the annual production quantity, \( C_u \) is the unit cost, \( \Delta Y \) is the change in yield, and \( M_s \) is the material savings per unit. This equation underscores the financial impact of process improvements in machine tool castings production.

Results and Performance Evaluation

After implementing the improvements, we monitored the production of machine tool castings to evaluate their effectiveness. The results from Scheme 1 (horizontal molding and vertical pouring) showed progress but were not fully satisfactory. The table below presents the production data for slip pillow components under this scheme over a two-month period.

| Product Name | Production Quantity (units) | Rejection Quantity (units) | Rejection Rate (%) | Predominant Defect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Tool Casting A (42200 Square Slip Pillow) | 4 | 2 | 50.00 | Gas Holes |

| Machine Tool Casting B (42160C Slip Pillow) | 11 | 7 | 63.64 | Gas Holes |

As evident, while inclusion defects were reduced, gas holes remained a significant issue, indicating that Scheme 1 did not fully address venting challenges in machine tool castings. This led us to transition to Scheme 2 (inclined pouring), which yielded markedly better results. The following table summarizes the outcomes after adopting inclined pouring for machine tool castings.

| Product Name | Production Quantity (units) | Rejection Quantity (units) | Rejection Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Tool Casting A (42200 Square Slip Pillow) | 8 | 1 | 12.50 |

| Machine Tool Casting B (42160C Slip Pillow) | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

The data demonstrates a substantial reduction in rejection rates, with one product achieving zero rejects. Visual inspection during pouring and post-processing confirmed fewer gas holes and inclusions, and no incidents of sand erosion or backfire were observed. The overall quality of machine tool castings improved significantly, with smoother surfaces and better dimensional accuracy. To quantify the improvement, we calculated the defect density before and after the changes using the formula: $$ D_d = \frac{N_d}{A_s} $$ where \( D_d \) is the defect density, \( N_d \) is the number of defects, and \( A_s \) is the surface area of the casting. For machine tool castings under Scheme 2, \( D_d \) decreased by over 70% compared to baseline levels.

Economically, the improvements translated into notable cost savings. For instance, the reduction in rejection rate by approximately 5% for an annual output of 40,000 pieces saved 290,000 currency units. The increase in process yield by 10% reduced iron consumption, saving 567,000 currency units annually, while core sand changes saved 238,000 currency units. Total annual savings reached 1.09 million currency units, validating the investment in process optimization for machine tool castings. Additionally, production efficiency gains of 30% ensured timely deliveries, enhancing customer satisfaction. The relationship between process parameters and savings can be modeled as: $$ S_{\text{total}} = f(\eta_p, \eta_y, C_m) $$ where \( \eta_p \) is production efficiency, \( \eta_y \) is yield efficiency, and \( C_m \) is material cost. This holistic approach underscores the value of integrated improvements in machine tool castings manufacturing.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our experience with improving the process for machine tool castings, particularly slip pillow components, highlights the importance of addressing specific defect mechanisms through tailored solutions. The transition from horizontal molding and vertical pouring to inclined pouring proved to be a critical step in overcoming gas hole and inclusion defects. Inclined pouring, by increasing the venting area and facilitating impurity flotation, effectively resolved the key challenges associated with these complex machine tool castings. The specialized production team further contributed to consistency and skill development, reducing human error and enhancing overall quality.

From a technical perspective, the mathematical models we developed, such as those for impurity separation and venting efficiency, provided a framework for understanding and optimizing the process. For example, the venting efficiency equation \( \eta_v = \frac{A_v}{V_c} \) emphasized the need to maximize \( A_v \) through design changes, which was achieved in Scheme 2. Similarly, the cost savings model \( S = (R_b – R_a) \cdot Q \cdot C_u + \Delta Y \cdot M_s \) demonstrated the tangible benefits of defect reduction in machine tool castings production. These models can be adapted to other casting applications, offering a generalizable approach to process improvement.

Looking ahead, we plan to further refine these methods for machine tool castings by incorporating advanced simulation tools and real-time monitoring. Potential areas for exploration include optimizing pouring angles based on computational fluid dynamics and automating core making to reduce variability. The success of this project underscores that continuous improvement is essential in the competitive field of machine tool castings, where even incremental gains can lead to significant economic and quality advantages.

In conclusion, the implementation of inclined pouring and organizational changes resulted in a dramatic improvement in the quality of machine tool castings, reducing rejection rates from over 50% to as low as 0% in some cases. This not only achieved substantial cost savings but also reinforced the value of a systematic, data-driven approach to manufacturing challenges. We recommend that others in the industry consider similar adaptations for complex machine tool castings, focusing on venting optimization and team specialization to enhance overall performance.