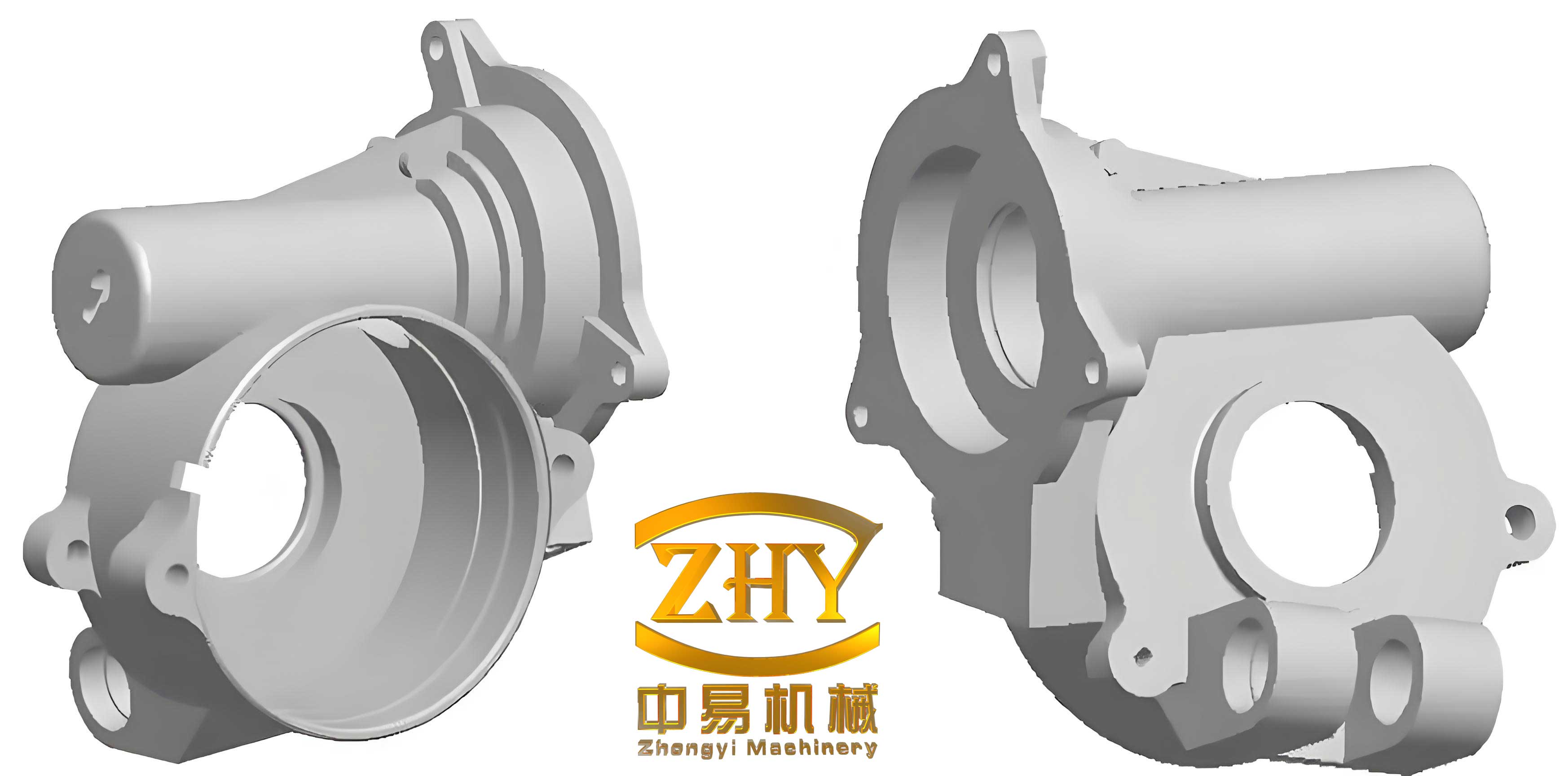

In the field of heavy-duty machinery, the demand for robust and reliable components is paramount. Among these, complex shell castings, such as rear axle housings and engine blocks, represent some of the most critical and challenging parts to produce. These shell castings must withstand significant structural loads and operational stresses, making their material integrity and dimensional accuracy non-negotiable. My extensive experience in foundry engineering, particularly using resin sand molding processes, has been focused on optimizing the production of such high-value shell castings. The following discussion synthesizes key methodologies and scientific principles essential for achieving consistent quality in gray iron shell castings, extending far beyond the basic process description.

The production of high-integrity shell castings begins with a fundamental understanding of the required service conditions. A rear axle housing for a high-horsepower tractor, for instance, requires a material grade like HT250 or HT300, which necessitates a predominantly pearlitic matrix with well-dispersed, type A graphite flakes. The mechanical properties are directly governed by the microstructure, which in turn is a function of chemical composition, cooling rate, and inoculation efficiency.

Metallurgical Design and Chemical Composition Control

The chemical composition is the blueprint for the final material properties. For high-strength gray iron shell castings, a careful balance must be struck to ensure strength, machinability, and castability. Carbon and silicon are the primary graphitizing elements, and their combined effect is often expressed as the Carbon Equivalent (CE), a critical parameter for predicting microstructure and avoiding undesirable chill.

$$CE = \%C + \frac{\%Si + \%P}{3}$$

For pearlitic grades like HT250, the CE is typically controlled in a range that promotes graphitization while maintaining strength, often between 3.9 and 4.1. However, the pursuit of higher strength, especially in thin sections of complex shell castings, often requires a lower CE and the use of alloying elements.

| Element | Target Range (wt.%) | Primary Function | Effect on Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.1 – 3.4 | Graphite formation, fluidity | Base for graphite; lower C increases strength but reduces fluidity. |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.7 – 2.1 | Graphitizer, strengthens ferrite | Promotes gray iron formation; high Si can reduce hardness and strength. |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.7 – 1.0 | Counteracts S, stabilizes pearlite | Combines with S to form MnS inclusions; essential for pearlite formation. |

| Phosphorus (P) | < 0.12 | Improves fluidity | Forms brittle phosphide eutectic; must be minimized in high-strength castings. |

| Sulfur (S) | 0.06 – 0.12 | Influences graphite morphology | Necessary for effective inoculation; combines with Mn. |

| Copper (Cu) | 0.3 – 0.6 | Pearlite refiner, mild strengthener | Improves uniformity of hardness across sections, reduces sensitivity. |

| Chromium (Cr) | 0.1 – 0.3 | Carbide stabilizer, strengthens | Increases strength and hardness; excess can promote chill in thin walls. |

The synergistic effect of copper and chromium is particularly valuable for shell castings with varying wall thicknesses. Copper promotes a fine, uniformly distributed pearlite structure without significantly increasing the chill tendency. Chromium increases the hardenability and solid-solution strengthens the matrix. Their combined addition can be modeled to approximate the resulting tensile strength (TS in MPa) contribution, though actual results depend on the base composition:

$$\Delta TS \approx 50 \times (\%Cu) + 80 \times (\%Cr) \quad \text{(Approximate contribution)}$$

This alloying strategy is crucial for ensuring that both thick and thin sections of a complex shell casting meet the required hardness and strength specifications, minimizing the risk of soft spots or unwanted carbides.

The Science and Practice of Inoculation

Inoculation is the controlled post-treatment of molten iron to enhance graphite nucleation. For shell castings, effective inoculation is non-negotiable to achieve type A graphite, avoid undercooled graphite (types D/E), and reduce section sensitivity. The process involves adding small amounts of ferro-silicon based inoculants containing active elements like Calcium (Ca), Aluminum (Al), and sometimes Barium (Ba) or Strontium (Sr).

The nucleation potency can be conceptualized by the fading effect, where the effectiveness of inoculation decays over time post-addition. The effective inoculation window is critical for the quality of shell castings. The fading kinetics can be simplified as:

$$N(t) = N_0 \cdot e^{-kt}$$

where \(N(t)\) is the number of active nuclei at time \(t\), \(N_0\) is the initial number after addition, and \(k\) is a fading rate constant dependent on temperature and iron chemistry. Therefore, practices like late stream inoculation or ladle inoculation with subsequent quick pouring are essential. The inoculant addition amount typically ranges from 0.2% to 0.4% of the molten metal weight. The reaction is also highly temperature-sensitive, necessitating precise control:

| Process Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Rationale for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculant Addition Point | Ladle during tapping / In-stream | Minimizes fading, ensures uniform distribution in the final casting. |

| Inoculant Amount | 0.2 – 0.4 wt.% | Sufficient to initiate copious nucleation; excess can lead to slag inclusion. | Metal Temperature at Inoculation | 1480 – 1520 °C | High enough for dissolution and dispersion, low enough to reduce fade. |

| Hold Time (Tap to Pour) | < 8 minutes | Critical to capitalize on peak nucleation before significant fading occurs. |

Gating System Design for Defect-Free Shell Castings

The design of the gating system for large, thin-walled shell castings must fulfill multiple objectives: smooth, non-turbulent filling to avoid oxide entrainment, adequate thermal control to prevent premature solidification in thin sections, and proper feeding dynamics. A top-gated, semi-pressurized system is often preferred for these castings. The key principle is to establish a rapid, but controlled, rise of metal in the mold cavity. The critical fill velocity \(v_c\) to avoid surface turbulence can be estimated based on the runner height \(h\):

$$v_c \leq \sqrt{2 g h}$$

where \(g\) is gravity. In practice, velocities are kept much lower. The gating ratio (\( \Sigma F_{choke} : \Sigma F_{runner} : \Sigma F_{ingate} \)) is designed to create a choke at the sprue base or runner, promoting a pressurized flow that minimizes air aspiration. A common ratio for gray iron shell castings is 1 : 1.2-1.5 : 1.1-1.3. The total ingate area \( \Sigma F_{ingate} \) is calculated based on the desired pouring time \(t\) (in seconds), the casting mass \(W\) (in kg), and an empirical constant \(k\) that accounts for fluidity and wall thickness:

$$\Sigma F_{ingate} = \frac{W}{k \cdot t}$$

For thin-walled iron castings, \(k\) can range from 0.5 to 0.7. For a 390 kg casting with a target fill time of 30 seconds, this calculates to a total ingate area of approximately 23-27 cm², often distributed across multiple ingates to ensure even filling of the complex shell casting geometry.

Mold Engineering and Dimensional Fidelity

Resin sand molds provide the dimensional stability and surface finish required for precision shell castings. The process involves creating a multi-core assembly. Dimensional control starts with applying the correct patternmaker’s shrinkage allowance. For gray iron, linear shrinkage is typically 0.7-1.0%, depending on the restraint from the mold and sand composition. This is modeled as:

$$L_{pattern} = L_{casting} \cdot (1 + \alpha)$$

where \( \alpha \) is the shrinkage allowance factor (e.g., 0.01 for 1%).

The core assembly design is paramount. Each core must have precisely engineered clearances (shrink/print) relative to the mold and other cores to account for thermal expansion of the sand and ensure easy assembly without causing crush or excessive gaps leading to fins. The use of master gauges and assembly fixtures is mandatory for complex shell castings. A simplified view of critical clearances for a typical assembly might include:

| Interface Location | Designed Clearance (mm) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Core to Mold (Vertical) | 0.5 – 1.5 | Prevents core lift during pouring, allows for sand expansion. |

| Core to Core (Sealing Face) | 0.0 – 0.2 | Minimizes metal penetration at core joints. |

| Core Print (Lateral) | 0.5 – 1.0 | Ensures precise location while allowing for variation. |

This systematic approach to tooling and assembly is what guarantees the internal and external dimensional accuracy of the final shell casting.

Melting, Purification, and Pouring Parameters

Modern induction melting provides excellent control over chemistry and temperature. However, the quality of molten iron is not defined by chemistry alone. The presence of dissolved gases (hydrogen, nitrogen) and non-metallic inclusions (oxides, sulfides) can severely compromise the mechanical properties of shell castings, leading to subsurface pinholes or reduced fatigue strength. Techniques like inert gas purging (e.g., argon) in the furnace or ladle are employed to reduce gas content. The effectiveness of degassing follows first-order kinetics relative to the partial pressure of the gas above the melt.

Pouring temperature is a critical compromise. Too low a temperature risks mistruns and cold shuts in thin sections; too high a temperature increases gas solubility, promotes mold erosion, and can lead to coarse graphite and shrinkage porosity. For typical HT250-300 shell castings with walls around 10mm, a pouring temperature range of 1380-1420°C is standard. The thermal modulus \(M\) of a section, defined as volume divided by cooling surface area (\(M = V/A\)), dictates its solidification time according to Chvorinov’s rule:

$$t_s = B \cdot M^n$$

where \(t_s\) is solidification time, \(B\) is a mold constant, and \(n\) is an exponent (typically ~2). Ensuring that the gating system delivers metal to thinner sections (lower \(M\)) before it begins to solidify in the runners is a key design goal for successful shell castings.

Quality Assurance and Performance Validation

The validation of the process for producing high-strength shell castings is multi-faceted. It involves destructive and non-destructive testing. Standard validation metrics include:

| Test Category | Method/Standard | Target for Shell Castings |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Properties | Tensile Test (ASTM A48) | UTS ≥ 250 MPa (HT250), ≥ 300 MPa (HT300) |

| Microstructure | Metallographic Analysis | Graphite: Type A, Size 3-5. Matrix: >90% Pearlite. |

| Soundness | Ultrasonic Testing, Pressure Test | No internal shrinkage or leaks at specified pressure. |

| Dimensional Accuracy | Coordinate Measurement Machine (CMM) | All critical features within drawing tolerance. |

A stable, optimized process should yield a consistent defect rate (scrap and rework) of less than 3% for such complex shell castings. This level of control is achieved not by focusing on a single parameter, but by understanding and managing the complex interrelationships between metallurgy, fluid dynamics, and thermal history that define the manufacture of premium gray iron shell castings. The continuous refinement of these factors—from the thermodynamics of alloying to the precision of core assembly—forms the bedrock of producing durable, high-performance components that meet the escalating demands of modern machinery.