In my extensive experience with casting processes, I have found that achieving high-quality shell castings, particularly for critical applications like valve components, is a complex endeavor. The demand for shell castings that can withstand extreme conditions—such as high temperature, high pressure, hydrogen service, high-pressure oxygen, high-sulfur resistance, cryogenic environments, and hazardous media—necessitates meticulous casting process design. Among these, the sequential directional solidification technique stands out as a classical method for producing thin-walled, multi-layered conical shell castings with stringent non-destructive testing requirements, including radiographic, ultrasonic, and magnetic particle inspection. This article delves into the intricacies of this process, focusing on its application to valve front shell castings, and provides a comprehensive analysis using mathematical models, tables, and practical insights.

The fundamental challenge with shell castings lies in ensuring structural integrity and defect-free formation during solidification. For valve front shell castings, which often feature a double-layer conical structure with uniform thin walls (e.g., 20 mm thickness), conventional casting methods fall short. Without specialized interventions, these shell castings are prone to defects like shrinkage porosity, cavities, and inclusions, compromising their performance. The sequential directional solidification process addresses this by creating a controlled thermal gradient that guides solidification from the coldest regions toward the risers, maintaining open feeding channels throughout. This approach is not merely a technical choice but a textbook model for producing premium shell castings.

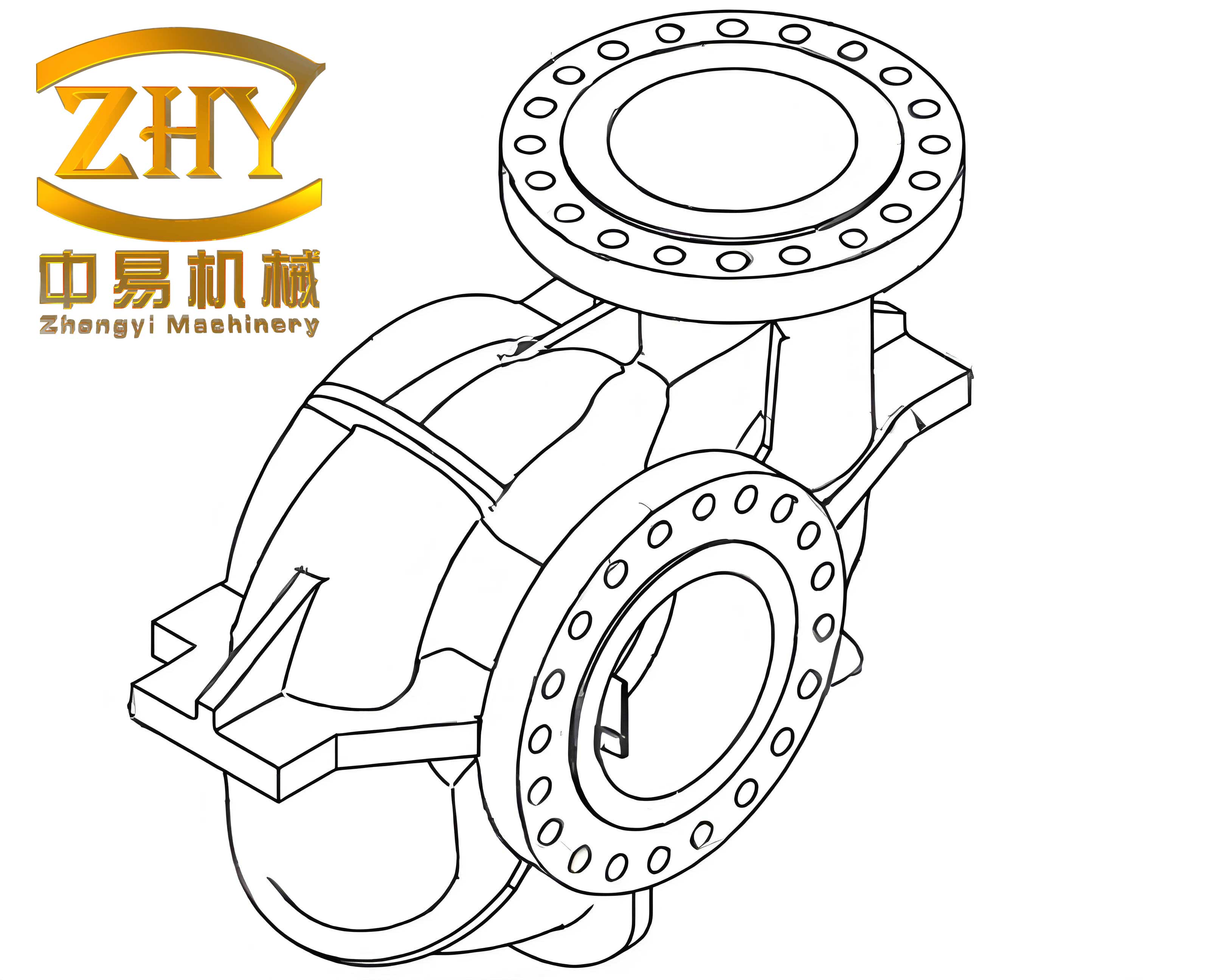

To elucidate the process, I will break down the key technological characteristics involved in crafting valve front shell castings. The core idea revolves around manipulating geometry, thermal management, and feeding systems to enforce directional solidification. Let’s begin with the geometric modifications essential for these shell castings.

The valve front shell casting consists of an outer conical shell and an inner conical shell, interconnected by ribs. To facilitate sequential solidification, the outer shell’s wall thickness is strategically increased. Specifically, the outer wall of the outer cone is thickened in the upper section, tapering down to the neck of the lower flange. This is achieved by designing a series of inscribed circles within the casting’s cross-section, where each successive circle’s diameter is enlarged by a factor of 1.3 to 1.8 relative to the previous one. Mathematically, if we denote the diameter of the first inscribed circle at the bottom as \( d_1 \), then the subsequent diameters follow a geometric progression:

$$ d_{n} = k \cdot d_{n-1} $$

where \( k \) ranges from 1.3 to 1.8, and \( n \) represents the circle index (e.g., \( n = 2, 3, \ldots, 7 \)). This progression generates a tapered profile that ensures a continuous temperature gradient toward the riser. The temperature gradient \( G \) along the vertical axis can be expressed as:

$$ G = \frac{\Delta T}{\Delta z} $$

where \( \Delta T \) is the temperature difference and \( \Delta z \) is the distance along the height. By thickening the wall, we enhance the thermal mass in upper regions, delaying solidification and maintaining a positive gradient \( G > 0 \) toward the riser. This is critical for shell castings to avoid isolated hot spots that lead to shrinkage defects.

Next, the placement of chills is paramount for initiating solidification in specific zones. For the valve front shell casting, external chills are arranged around the lower flange and its neck. These chills are designed as small blocks with dimensions proportional to the casting wall thickness. The chill dimensions and layout can be summarized in the following table:

| Chill Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Length-to-Width Ratio | 2:1 (length is twice the width) |

| Width Relative to Casting | 1 to 1.5 times the casting width at the location |

| Thickness Relative to Casting | 1 to 1.5 times the local casting thickness |

| Angular Spacing Between Chills | 30° to 60° |

| Distance Between Chills | 3 to 5 mm |

This configuration ensures that the lower flange and neck solidify prior to the outer conical shell, establishing a sequential solidification front. The chills act as heat sinks, extracting heat rapidly and creating a steep thermal gradient that promotes directional growth. For shell castings, this is vital to prevent shrinkage in the conical sections, as the colder regions solidify first and are progressively fed by the hotter riser metal.

Similarly, the inner conical shell requires tailored geometry. Its inner wall is thickened upward to form a similar taper, ensuring a temperature gradient toward the riser. The inner shell’s solidification must be synchronized with the outer shell to avoid conflicts. Given that the inner shell is fed through six ribs (each 20 mm thick), the entering metal is cooler due to heat loss. To compensate, the bottom inner wall is thickened by an additional 6 mm (from 20 mm to 26 mm), increasing thermal capacity. Moreover, three Ø6 mm vent holes are drilled in the core at this location, and insulated external chills (known as “sand-isolated chills”) are placed to accelerate solidification at the lowest point, mitigating gas entrapment and slag inclusion. This attention to detail is what sets high-performance shell castings apart.

The gating and risering system plays a pivotal role. The entire casting is placed in the drag (lower mold half) to minimize dimensional deviations during molding and closing. The gating system is designed to inject metal tangentially from the bottom flange area, allowing for spiral upward flow that scrubs away gases and impurities, directing them toward the risers. Four insulated heated open risers are positioned across the upper plane of the top flange and inner cone. These risers have dimensions \( L \times B \times H \) (length × width × height) and are strategically placed to feed both conical shells. During pouring, once the metal level reaches one-third of the riser height, the pouring method switches to direct diagonal feeding into the risers. This serves two purposes: it introduces hotter metal to elevate riser temperature, enhancing the thermal gradient, and the kinetic energy from pouring disrupts dendrites, improving feeding efficiency.

The process yield \( N \) for high-quality shell castings is a key metric, calculated as:

$$ N = \frac{W_z}{W_j + W_m + W_z} \times 100\% $$

where \( W_z \) is the casting weight, \( W_j \) is the gating system weight, and \( W_m \) is the riser weight. For a typical valve front shell casting with \( W_z = 235.4 \, \text{kg} \), \( W_m = 420 \, \text{kg} \), and \( W_j = 20 \, \text{kg} \), we compute:

$$ N = \frac{235.4}{20 + 420 + 235.4} \times 100\% \approx 39\% $$

This low yield underscores the extensive feeding measures employed, which are necessary to achieve dense, shrinkage-free shell castings. After pouring, insulating coverings are applied to the risers to prolong solidification time, further augmenting feeding capability.

To validate the efficacy of this process, rigorous non-destructive testing is conducted on the shell castings. The requirements include 100% radiographic inspection where feasible, 100% magnetic particle inspection, and ultrasonic testing on machined surfaces. The standards adhered to are akin to JB/T 6440 for radiography, JB/T 6439 for magnetic particle, and GB/T 7233.1 for ultrasonic testing. The results from radiographic inspection of a batch of valve front shell castings are summarized below:

| Inspection Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Films Taken | 24 |

| Defect-Free Films | 20 |

| Films with Gas Porosity (Class I) | 3 |

| Films with Gas Porosity (Class II) | 1 |

| Films with Shrinkage Cavities (Class I/II) | 0 |

| Films with Inclusions (Class I/II) | 0 |

| Films with Shrinkage Porosity (Class I/II) | 0 |

The percentage breakdown is as follows: defect-free films constitute 83.3%, Class I defect films (gas porosity) 12.5%, and Class II defect films 4.2%. No shrinkage or inclusion defects are detected, confirming the superiority of the sequential directional solidification process for producing high-integrity shell castings. These results align with the stringent criteria for valves used in critical services, such as high-pressure hydrogen applications.

Delving deeper into the thermal dynamics, the success of sequential directional solidification for shell castings hinges on maintaining a consistent temperature gradient. This can be modeled using Fourier’s law of heat conduction and solidification kinetics. The temperature field \( T(x,y,z,t) \) in the casting during solidification obeys the heat equation:

$$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T $$

where \( \alpha \) is the thermal diffusivity. For directional solidification, we desire a uniaxial gradient along the vertical direction \( z \), such that \( \frac{\partial T}{\partial z} > 0 \) (increasing toward the riser). The geometric tapering and chills help achieve this by modulating the heat flux. The solidification time \( t_s \) for a section of thickness \( s \) can be estimated using Chvorinov’s rule:

$$ t_s = C \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where \( V \) is volume, \( A \) is surface area, \( C \) is a constant dependent on mold material and metal properties, and \( n \) is an exponent typically near 2. For tapered sections in shell castings, the \( V/A \) ratio increases upward, leading to longer solidification times at the top, which aligns with directional feeding.

Furthermore, the use of insulated heated risers introduces additional heat input, which can be quantified. The riser’s heating effect can be modeled as an additional heat source term \( Q_r \) in the energy balance. The overall thermal efficiency \( \eta \) of the feeding system for shell castings can be defined as:

$$ \eta = \frac{\text{Volume of sound casting}}{\text{Total volume of metal poured}} \times 100\% $$

In our case, with a process yield of 39%, the emphasis is on quality over material efficiency, which is acceptable for premium shell castings.

The application of this process extends beyond valve front shell castings to other complex multi-layered structures. The principles of sequential directional solidification—geometric tapering, strategic chilling, thermal gradient control, and optimized risering—are universally applicable. For instance, in aerospace or energy sector components where thin-walled shell castings are prevalent, this methodology can be adapted to ensure reliability. The key is to customize the parameters based on casting geometry, alloy properties, and performance requirements.

In conclusion, the sequential directional solidification process represents a pinnacle in casting technology for producing high-quality shell castings. Through meticulous design involving wall thickening, chill placement, temperature gradient formation, and advanced risering, it is possible to achieve defect-free shell castings that meet rigorous non-destructive testing standards. The mathematical models and empirical data presented herein underscore the process’s robustness. As casting complexity continues to grow, especially for double or multi-layered shell castings, this approach offers a reliable framework for innovation and quality assurance. Future work may explore computational simulations to further optimize the process for specific shell casting configurations, but the foundational principles remain steadfast.