In the high-precision world of automotive manufacturing, investment casting, or the lost-wax process, stands out for its ability to produce components with exceptional dimensional accuracy and complex geometries. Among these critical components are valve rocker arms, pivotal elements in an engine’s valvetrain responsible for translating camshaft rotation into the linear motion that opens and closes valves. The performance and longevity of an engine are heavily dependent on the structural integrity of these parts. Consequently, any internal defect, particularly porosity in casting, is a major concern as it can act as a stress concentrator, leading to premature failure under cyclic loading. Achieving near-net-shape castings with minimal machining allowance places an even higher demand on flawless internal quality. This analysis delves into the root causes of porosity in casting defects within investment-cast valve rocker arms and outlines a systematic, process-driven approach for their mitigation.

The challenge of porosity in casting is not monolithic; it manifests in several distinct forms, each with a unique formation mechanism. Understanding this taxonomy is the first step toward effective remediation. The primary classifications relevant to investment casting are:

| Porosity Type | Formation Mechanism | Typical Location & Morphology |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Evolved (or Precipitation) Porosity | Gases (primarily H₂, N₂) dissolve in the molten metal during melting. Upon solidification, their solubility drops sharply, causing them to precipitate out as bubbles. If these bubbles cannot float to the surface and escape before the metal solidifies, they become trapped. | Often found in the last-to-freeze regions of a casting (e.g., thermal centers, thick sections). Pores are usually small, spherical, and distributed fairly uniformly. |

| 2. Entrapped (or Inclusions-Related) Porosity | Closely linked to slag or dross entrapment. Gases can be trapped by the folding in of the oxide film on the molten metal surface during turbulent filling, or can nucleate on non-metallic inclusions. | Located just below the casting surface or near ingates. Pores are often irregular, associated with oxide films, and may appear oxidized. |

| 3. Invasive (or Mold-Gas) Porosity | Generated from the mold or shell itself. Residual moisture, binders, or volatiles in the ceramic shell thermally decompose during metal pouring, generating gas. If the shell permeability is too low, this gas pressure can penetrate the solidifying metal skin. | Typically located at or just beneath the casting surface. Pores can be large, smooth, and sometimes elongated in the direction of gas invasion. |

| 4. Reaction (or Shrinkage-Assisted) Porosity | Often a synergistic defect. As the metal shrinks during solidification, it can create micro-shrinkage cavities. Concurrent gas precipitation can expand these cavities, leading to larger, more irregular pores than from shrinkage alone. | Located in isolated hot spots or interdendritic regions. Pores have an irregular, dendritic, or jagged appearance. |

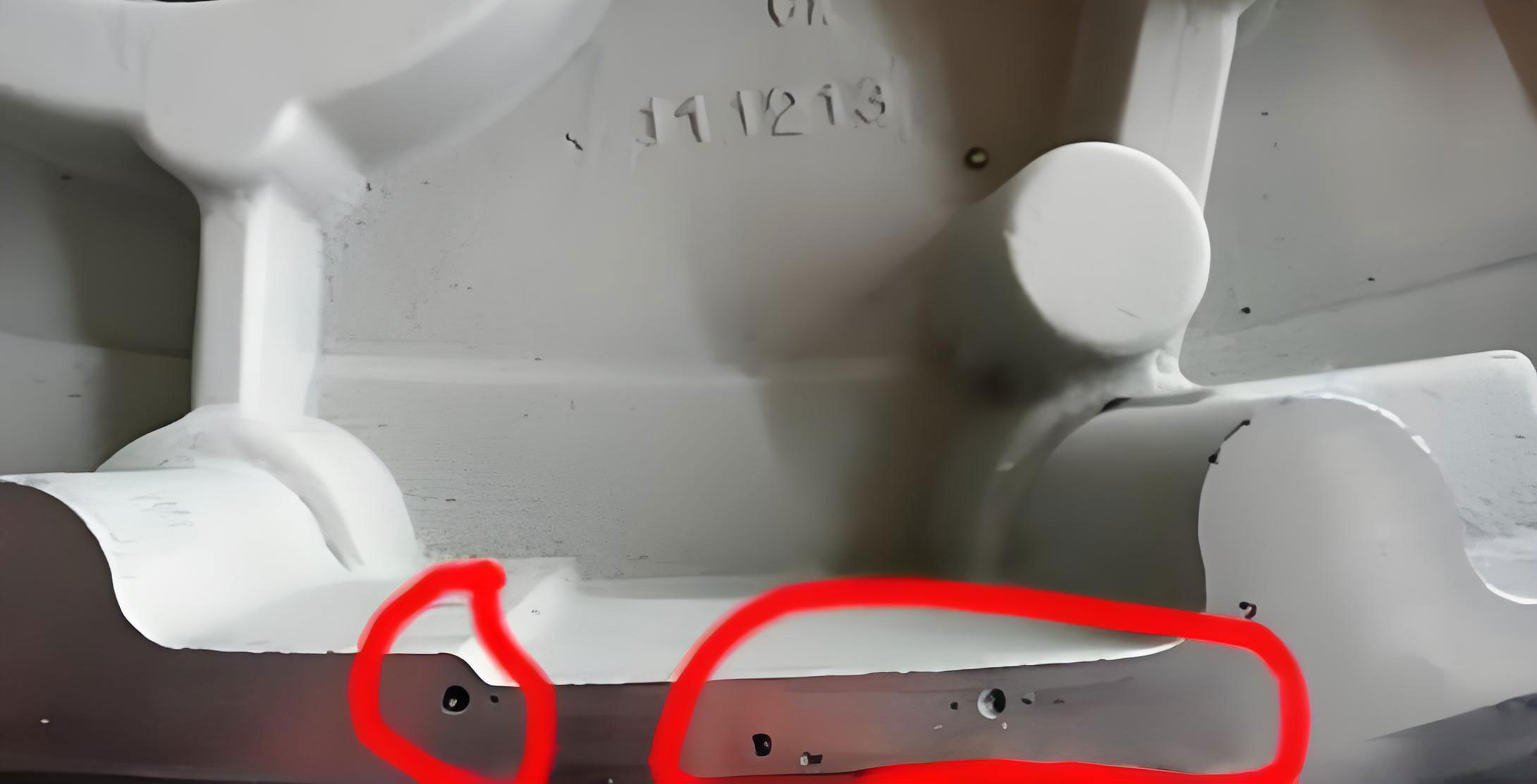

A targeted investigation into valve rocker arm rejects often reveals that the dominant forms of porosity in casting are evolved and invasive porosity. Their co-occurrence points to specific vulnerabilities in the traditional investment casting process chain. Let’s dissect the primary contributing factors:

Shell-Related Causes (Leading to Invasive Porosity): The ceramic shell is not an inert container; it is a potential source of gas. In processes using waterglass or certain polymer-based binders, incomplete burnout of the wax and insufficient removal of chemically bound water from the colloidal silica or binders are common pitfalls. A shell fired at too low a temperature or for too short a time retains volatile compounds. During metal pour, the thermal shock causes rapid gas generation. The permeability of the shell, governed by pore size and interconnectivity, is critical. It can be approximated by Darcy’s Law for flow through a porous medium:

$$ Q = \frac{k A \Delta P}{\mu L} $$

where \( Q \) is the gas flow rate, \( k \) is the shell permeability, \( A \) is the area, \( \Delta P \) is the pressure differential, \( \mu \) is the gas viscosity, and \( L \) is the shell thickness. A low \( k \) value (low permeability) directly increases the pressure \( \Delta P \) at the metal-shell interface, forcing gas into the casting.

Metal-Related Causes (Leading to Evolved Porosity): The charge materials are a primary source of hydrogen, the most problematic gas in ferrous casting. Rust (Fe₂O₃·nH₂O) on steel scrap or pig iron reacts at high temperature:

$$ 2Al_{(in melt)} + 3H_2O_{(from rust)} \rightarrow Al_2O_3 + 3H_2 \uparrow $$

The dissolved hydrogen level in molten iron follows Sieverts’ Law:

$$ [H] = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}} $$

where [H] is the dissolved hydrogen concentration, \( K_H \) is the equilibrium constant (temperature-dependent), and \( P_{H_2} \) is the partial pressure of hydrogen at the melt surface. Moisture in the atmosphere, lining, or tools increases \( P_{H_2} \), raising [H]. Inoculants and nodularizers containing aluminum can exacerbate this reaction. During solidification, the solubility plummets, leading to hydrogen precipitation and porosity in casting.

Process Parameter Causes (Exacerbating All Porosity Types): Suboptimal thermal and kinetic parameters during pouring create a perfect storm for defect formation. Low pouring temperature increases metal viscosity (\( \mu_{metal} \)), which is a key factor in Stokes’ Law governing bubble flotation velocity:

$$ v = \frac{2 g r^2 ( \rho_{metal} – \rho_{gas})}{9 \mu_{metal}} $$

where \( v \) is the terminal velocity, \( g \) is gravity, \( r \) is the bubble radius. A high \( \mu_{metal} \) drastically reduces \( v \), trapping bubbles. Furthermore, a low pouring temperature shortens the “feeding window” or “riser efficiency time,” making it harder for both gas and liquid metal to compensate for shrinkage. Conversely, excessively high pouring temperatures can increase gas solubility and metal-mold reaction severity. Slow pouring extends the filling time, leading to excessive heat loss from the metal and increased exposure of the flowing stream to air, promoting oxide formation (entrapped porosity).

Combating porosity in casting requires a holistic, multi-front strategy targeting each stage of the process. The following integrated measures have proven effective in dramatically reducing defect rates.

1. Optimizing Shell Permeability and Burnout: This is the first line of defense against invasive porosity. The goal is to maximize \( k \) (permeability) in the shell while minimizing its gas-generating potential.

- Extended and Controlled Drying: Each slurry and stucco coat must be thoroughly dried before applying the next. Inadequate drying traps liquid within the shell wall. Increasing primary coat drying time from 24 to 36+ hours in a controlled humidity environment ensures complete hydrolysis and gelling of the binder, creating a more open structure.

- Enhanced Dewaxing and Firing Cycle: The shell firing cycle must ensure complete removal of wax patterns and organic modifiers, followed by sintering of the ceramic to develop strength without closing surface pores. Increasing the peak firing temperature from 800-850°C to 860-910°C and extending the hold time from 1-1.5 hours to 2-2.5 hours ensures:

- Complete combustion/volatilization of organics (no black “carbon” core).

- Dehydration of colloidal silica: $$ \equiv Si-OH + HO-Si \equiv \rightarrow \equiv Si-O-Si \equiv + H_2O \uparrow $$ This reaction strengthens the shell but must be managed to avoid over-sintering which reduces permeability.

- Permeability-Enhancing Additives: Incorporating fine, leachable or combustible fibers (e.g., phenolic microspheres) into the backup coats can create interconnected micro-channels, significantly boosting post-firing permeability.

2. Minimizing Melt Gas Content (Source Control for Evolved Porosity):

- Charge Material Quality: Implement strict controls on charge materials. Scrap must be clean, degreased, and de-rusted. The use of pre-blended, high-quality virgin iron and steel briquettes minimizes surface oxidation and moisture.

- Effective Melt Deoxidation and Degassing: For ferrous alloys, effective deoxidation reduces the oxygen potential, which in turn lowers hydrogen pickup. Practices include the use of aluminum-based deoxidizers (carefully controlled to avoid Al₂O₃ inclusions) or vacuum melting/degasification where feasible. The reaction is favored: $$ [O] + [H] \leftrightarrow (H_2O)_{gas} $$ Low [O] leads to low [H].

- Inoculant/Nodularizer Selection: Choose low-aluminum or aluminum-free inoculants and nodularizers for ductile iron to avoid the hydrogen-generating reaction mentioned earlier.

3. Precise Thermal and Kinetic Control During Pouring: This is the operational core of minimizing porosity in casting. The goal is to maintain high fluidity for bubble flotation while managing solidification dynamics.

| Process Parameter | Original (Problematic) Range | Optimized Range | Rationale & Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melt Superheat (Tapping Temp.) | 1480-1500°C | 1580-1600°C | Provides adequate thermal mass to account for heat loss during transfer, holding, and pouring. Ensures metal is well above liquidus, promoting inclusion flotation. |

| Pouring Temperature (into mold) | 1300-1350°C | 1400-1450°C | Directly reduces molten metal viscosity (\( \mu_{metal} \)), increasing bubble flotation velocity (\( v \uparrow \)) per Stokes’ Law. Extends the fluid life for feeding. |

| Pouring Time (for a cluster) | 5-6 seconds | 3-4 seconds | Reduces total heat loss and exposure to air during filling. Increases thermal gradient, promoting directional solidification. Must be balanced to avoid turbulent entrainment. |

| Shell (Mold) Temperature | Ambient (~25°C) | 200-400°C (post-firing, held) | Reduces thermal shock, slowing the rate of gas generation from the shell. Prevents premature freezing of metal at the thin sections/ingates, improving feed paths. |

The relationship between pouring temperature and defect rate is often parabolic. The optimized window (1400-1450°C in this case) balances fluidity against increased gas solubility and metal-mold reaction rates. Data from process validation typically shows a clear minimum:

| Pouring Temperature Range (°C) | Observed Porosity Rejection Rate (%) | Dominant Porosity Type & Other Issues |

|---|---|---|

| 1300-1350 | 9.1 – 9.3 | High evolved & shrinkage-assisted porosity; cold shuts, mistuns. |

| 1350-1400 | 4.3 – 5.1 | Moderate evolved porosity; some entrapped slag. |

| 1400-1450 | 1.6 – 2.3 | Minimal porosity across all types. |

| 1450-1500 | 3.2 – 4.3 | Increased reaction/invasive porosity; surface roughness, penetration. |

4. Optimized Gating and Solidification Design: While not the primary focus of the initial text, this is a critical supporting strategy. The gating system should be designed to:

- Fill the mold cavity smoothly with minimal turbulence (e.g., using tapered sprue, flow diffusers) to prevent oxide entrainment and bubble entrapment.

- Establish a strong thermal gradient, directing solidification from the farthest points back toward the riser(s). This progressive solidification allows dissolved gases to be pushed into the riser, which is later removed. Chills can be used strategically on thick sections like the boss of a rocker arm to prevent isolated hot spots where porosity in casting nucleates.

The implementation of this integrated approach—enhancing shell properties, controlling melt gas, and precisely managing pouring parameters—yields dramatic results. Rejection rates due to porosity in casting defects, which were persistently above 9%, can be consistently reduced to the range of 2-3%. This represents a significant improvement in production yield, cost efficiency, and component reliability.

In conclusion, porosity in casting in investment-cast components like valve rocker arms is a multifaceted problem stemming from interactions between the shell, the metal, and the process dynamics. It is not sufficient to address only one factor. A successful reduction strategy requires a systemic analysis and the synchronized optimization of the entire process chain: from shell build-up and firing, through melt preparation and treatment, to the critical control of thermal and kinetic parameters during mold filling. The principles outlined here—centered on permeability management, source gas reduction, and thermal control—provide a robust framework for diagnosing and eliminating porosity in casting, pushing quality levels closer to the zero-defect ideal demanded by modern high-performance automotive engineering.